By Gabrielle Banks and Keri Blakinger

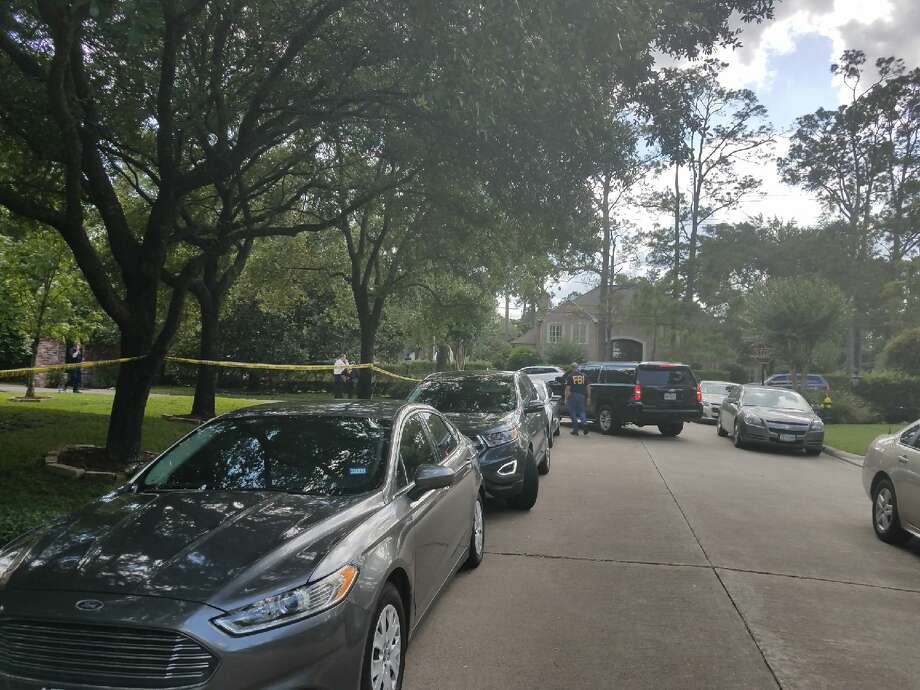

The FBI and other federal authorities raided a ritzy Hedwig Village home Tuesday.

Six technology experts in the Houston area have been charged with stealing trade secrets from a Houston engineering company and slipping them to a manufacturer in China in what investigators said was an effort by the Chinese government to become a worldwide marine power.

The Chinese manufacturer tried to use the same stolen trade technology to sell products back to the U.S. company at "significantly reduced prices," according to court documents.

The product at the center of the thefts is called syntactic foam, a high-performance buoyancy agent that can be used in both civilian and military projects for oil exploration, aerospace, submarines and what prosecutors termed "stealth technology."

The Houston company is not identified in court papers unsealed Wednesday, but is a global engineering firm considered a leader in marine technology, particularly in the production of syntactic foam, according to court documents.

The arrests were announced Wednesday, a day after federal agents armed with a search warrant swept through the $1.6 million Hedwig Village home of Shan Shi, 52, who authorities say was hired as a consultant by the Chinese manufacturer to set up a company to push marine buoyancy technology.

Shi was among four U.S. citizens charged in the federal complaint, along with Uka Kalu Uche, 35, of Spring; Samuel Abotar Ogoe, 74, of Missouri City; and Johnny Wade Randall, 48, of Conroe.

Also charged were Houston residents, Kui Bo, 40, a Canadian citizen, and Gang Liu, 31, a Chinese national with permanent resident status.

Hui Huang, 32, who lives in China and works for the Chinese manufacturing firm in Zhejiang Province, was also charged.

All are charged in federal court in the District of Columbia with conspiracy to commit theft of trade secrets, which carries a maximum sentence of 10 years in prison and financial penalties.

A civil forfeiture complaint was also filed in Washington, D.C., for properties officials say were used for or in connection with illegal conduct.

The Chinese manufacturing company intended to sell syntactic foam as part of a push to meet China's national goals of boosting its marine engineering industry, according to federal officials.

The investigation was led by the FBI's Houston field office, the U.S. Department of Commerce's Bureau of Industry and Security export enforcement office and the Internal Revenue Service's Criminal Investigation Unit.

The scheme played out over a five-year period, from 2012 to May 2017, according to the criminal complaint.

Shi set up a Houston company -- first known as Optimax International Inc. and later renamed Offshore Dynamics Inc. -- that billed itself as an engineering consultant to oil and gas companies, according to an sworn statement from an FBI special agent from Houston.

The sole owner of the company is the Chinese manufacturing firm, records show.

The company then began recruiting well-placed employees at local competitors, hiring away several who had knowledge of the U.S. company's technology, according to court documents.

Investigators traced 23 wire transfers of $2.2 million sent from China to the Houston site, apparently to fund the scheme.

Proprietary information -- some of which was privy to just a half-dozen of the 400 employees at the U.S. company -- was eventually shipped back to the Chinese manufacturer, according to court records.

In one email sent April 14, 2015, Huang asks Shi and Bo to provide specific details on how to manufacture syntactic foam, according to the complaint.

"I need information regarding formula, preparation process and performance of the syntactic materials," Huang said in the email.

By 2016, the upstart company became a bit more brazen.

The Chinese manufacturing company intended to sell syntactic foam as part of a push to meet China's national goals of boosting its marine engineering industry, according to federal officials.

The investigation was led by the FBI's Houston field office, the U.S. Department of Commerce's Bureau of Industry and Security export enforcement office and the Internal Revenue Service's Criminal Investigation Unit.

The scheme played out over a five-year period, from 2012 to May 2017, according to the criminal complaint.

Shi set up a Houston company -- first known as Optimax International Inc. and later renamed Offshore Dynamics Inc. -- that billed itself as an engineering consultant to oil and gas companies, according to an sworn statement from an FBI special agent from Houston.

The sole owner of the company is the Chinese manufacturing firm, records show.

The company then began recruiting well-placed employees at local competitors, hiring away several who had knowledge of the U.S. company's technology, according to court documents.

Investigators traced 23 wire transfers of $2.2 million sent from China to the Houston site, apparently to fund the scheme.

Proprietary information -- some of which was privy to just a half-dozen of the 400 employees at the U.S. company -- was eventually shipped back to the Chinese manufacturer, according to court records.

In one email sent April 14, 2015, Huang asks Shi and Bo to provide specific details on how to manufacture syntactic foam, according to the complaint.

"I need information regarding formula, preparation process and performance of the syntactic materials," Huang said in the email.

By 2016, the upstart company became a bit more brazen.

An official at the U.S. company told the FBI that in October 2016, Shi and Huang offered to produce spheres in China for less than what it cost the American company to make them.

The person trying to cut the deal "even offered to sign an exclusivity agreement" if the American company bought a large enough quantity of macrospheres.

The person trying to cut the deal "even offered to sign an exclusivity agreement" if the American company bought a large enough quantity of macrospheres.

The company official visited the Chinese plant to consider the offer.

"The main rationale for considering the deal was to block [the U.S. company's] competitors from gaining access to cheaper macrospheres," according to the statement from the FBI agent.

The company official was surprised by how quickly the imitation company "had been able to develop quality products," he said.

The FBI operation kicked in when the Chinese-backed company began offering its technology and making deals with other companies for underwater vehicles.

It's hard to put an exact dollar value on it, but trade secret theft is a massive underground market, powered by Chinese interests.

A report this year by the bipartisan, nongovernmental Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property described China as the "world's principal IP infringer."

"The main rationale for considering the deal was to block [the U.S. company's] competitors from gaining access to cheaper macrospheres," according to the statement from the FBI agent.

The company official was surprised by how quickly the imitation company "had been able to develop quality products," he said.

The FBI operation kicked in when the Chinese-backed company began offering its technology and making deals with other companies for underwater vehicles.

It's hard to put an exact dollar value on it, but trade secret theft is a massive underground market, powered by Chinese interests.

A report this year by the bipartisan, nongovernmental Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property described China as the "world's principal IP infringer."

Purloined trade secrets -- in combination with more quantifiable thefts, such as counterfeit goods and pirated software -- cost the U.S. at least $225 billion per year, and possibly as much as $600 billion.

Less than a week before the most recent arrests, a Chinese man pleaded guilty in federal court on charges of economic espionage and trade secret theft.

Less than a week before the most recent arrests, a Chinese man pleaded guilty in federal court on charges of economic espionage and trade secret theft.

The ex-IBM employee stole computer code with the intent to benefit the National Health and Planning Commission of the People's Republic of China.

U.S. companies don't report such thefts, given the costs of pursuing redress and the possible negative impacts on stock prices.

U.S. companies don't report such thefts, given the costs of pursuing redress and the possible negative impacts on stock prices.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire