Scientists are raising questions about the ethics of studies backed by Chinese surveillance agencies. Prestigious journals are taking action.

By Sui-Lee Wee and Paul Mozur

Kashgar, a city in East Turkestan, the colony where China has locked up more than one million people from predominantly Muslim minority groups.

BEIJING — China’s efforts to study the DNA of the country’s ethnic minorities have incited a growing backlash from the global scientific community, as scientists warn that Beijing uses its growing knowledge to spy on and oppress its people.

Two publishers of prestigious scientific journals, Springer Nature and Wiley, said this week that they would re-evaluate papers they previously published on Tibetans, Uighurs and other minority groups. The papers were written or co-written by scientists backed by the Chinese government, and the two publishers want to make sure the authors got consent from the people they studied.

Springer Nature, which publishes the influential journal Nature, also said that it was toughening its guidelines to make sure scientists get consent, particularly if those people are members of a vulnerable group.

The statements followed articles by The New York Times that describe how the Chinese authorities are trying to harness bleeding-edge technology and science to track minority groups.

Two publishers of prestigious scientific journals, Springer Nature and Wiley, said this week that they would re-evaluate papers they previously published on Tibetans, Uighurs and other minority groups. The papers were written or co-written by scientists backed by the Chinese government, and the two publishers want to make sure the authors got consent from the people they studied.

Springer Nature, which publishes the influential journal Nature, also said that it was toughening its guidelines to make sure scientists get consent, particularly if those people are members of a vulnerable group.

The statements followed articles by The New York Times that describe how the Chinese authorities are trying to harness bleeding-edge technology and science to track minority groups.

The issue is particularly stark in East Turkestan, a colony on China’s western frontier, where the authorities have locked up more than one million Uighurs and other members of predominantly Muslim minority groups in concentration camps in the name of quelling "terrorism".

Chinese companies are selling facial recognition systems that they claim can tell when a person is a Uighur.

Chinese companies are selling facial recognition systems that they claim can tell when a person is a Uighur.

Chinese officials have also collected blood samples from Uighurs and others to build new tools for tracking members of minority groups.Western scientists and companies have provided help for those efforts.

That has included publishing papers in high-profile journals, which grants prestige and respectability to the authors that can lead to access to funding, data or new techniques.

When Western journals publish such papers by Chinese scientists affiliated with the country’s surveillance agencies, it amounts to selling a knife to a friend “knowing that your friend would use the knife to kill his wife,” said Yves Moreau, a professor of engineering at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium.

On Tuesday, Nature published an essay by Dr. Moreau calling for all publications to retract papers written by scientists backed by Chinese security agencies that focus on the DNA of minority ethnic groups.

“If you produce a piece of knowledge and know someone is going to take that and harm someone with it, that’s a huge problem,” said Dr. Moreau.

When Western journals publish such papers by Chinese scientists affiliated with the country’s surveillance agencies, it amounts to selling a knife to a friend “knowing that your friend would use the knife to kill his wife,” said Yves Moreau, a professor of engineering at the Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium.

On Tuesday, Nature published an essay by Dr. Moreau calling for all publications to retract papers written by scientists backed by Chinese security agencies that focus on the DNA of minority ethnic groups.

“If you produce a piece of knowledge and know someone is going to take that and harm someone with it, that’s a huge problem,” said Dr. Moreau.

Yves Moreau, an engineering professor in Belgium, is calling for publications to retract papers written by scientists backed by Chinese security agencies that focus on the DNA of minority ethnic groups.

The scientific reaction is part of a broader backlash to China’s actions in East Turkestan.

Lawmakers in the United States and elsewhere are taking an increasingly critical stance toward Beijing’s policies.

On Tuesday, the House voted almost unanimously for a bill condemning China’s treatment of Uighurs and others.

Dr. Moreau and other scientists worry that China’s research into the genes and personal data of ethnic minorities is being used to build databases, facial recognition systems and other methods for monitoring and subjugating China’s ethnic minorities.

They also worry that research into DNA in particular violates widely followed scientific rules involving consent.

They also worry that research into DNA in particular violates widely followed scientific rules involving consent.

In East Turkestan, where so many people have been confined to concentration camps and a heavy police presence dominates daily life, they say, it is impossible to verify that Uighurs have given their blood samples willingly.

China’s Ministry of Public Security and the Ministry of Science and Technology did not respond to requests for comment.

In September, Dr. Moreau and three other scientists asked Wiley to retract a paper on the faces of minorities it published last year, citing the potential for abuse and the tone of discussion about race.

“The point of this work was to improve surveillance capabilities on all Tibetans and Uighurs,” said Jack Poulson, a former Google research scientist and founder of the advocacy group Tech Inquiry, and another member of the group that reached out to Wiley.

China’s Ministry of Public Security and the Ministry of Science and Technology did not respond to requests for comment.

In September, Dr. Moreau and three other scientists asked Wiley to retract a paper on the faces of minorities it published last year, citing the potential for abuse and the tone of discussion about race.

“The point of this work was to improve surveillance capabilities on all Tibetans and Uighurs,” said Jack Poulson, a former Google research scientist and founder of the advocacy group Tech Inquiry, and another member of the group that reached out to Wiley.

Even if the authors obtained consent from those they studied, he added, that would be “insufficient to satisfy their ethical obligations.”

“The point of this work was to improve surveillance capabilities on all Tibetans and Uighurs,” said Jack Poulson, a former Google research scientist.

“The point of this work was to improve surveillance capabilities on all Tibetans and Uighurs,” said Jack Poulson, a former Google research scientist.

Wiley initially declined, but said this week that it would reconsider.

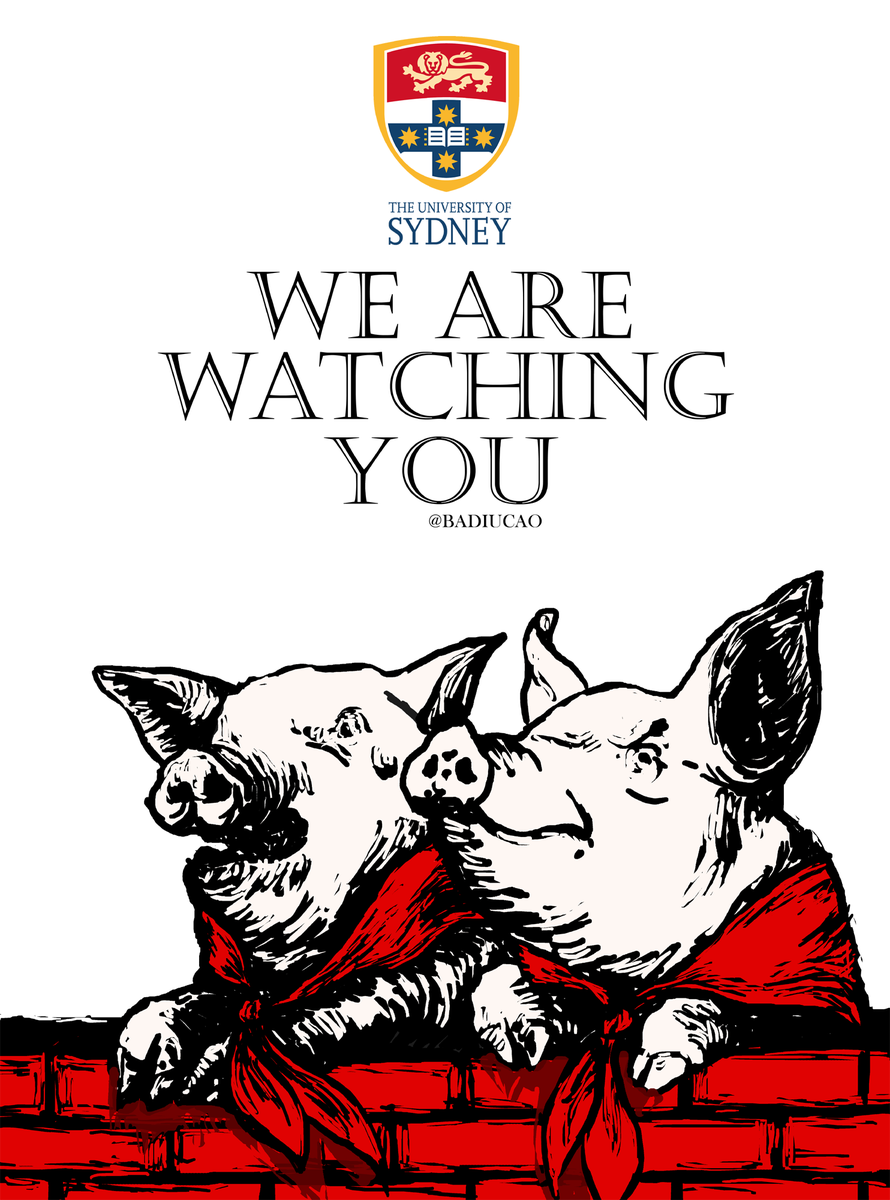

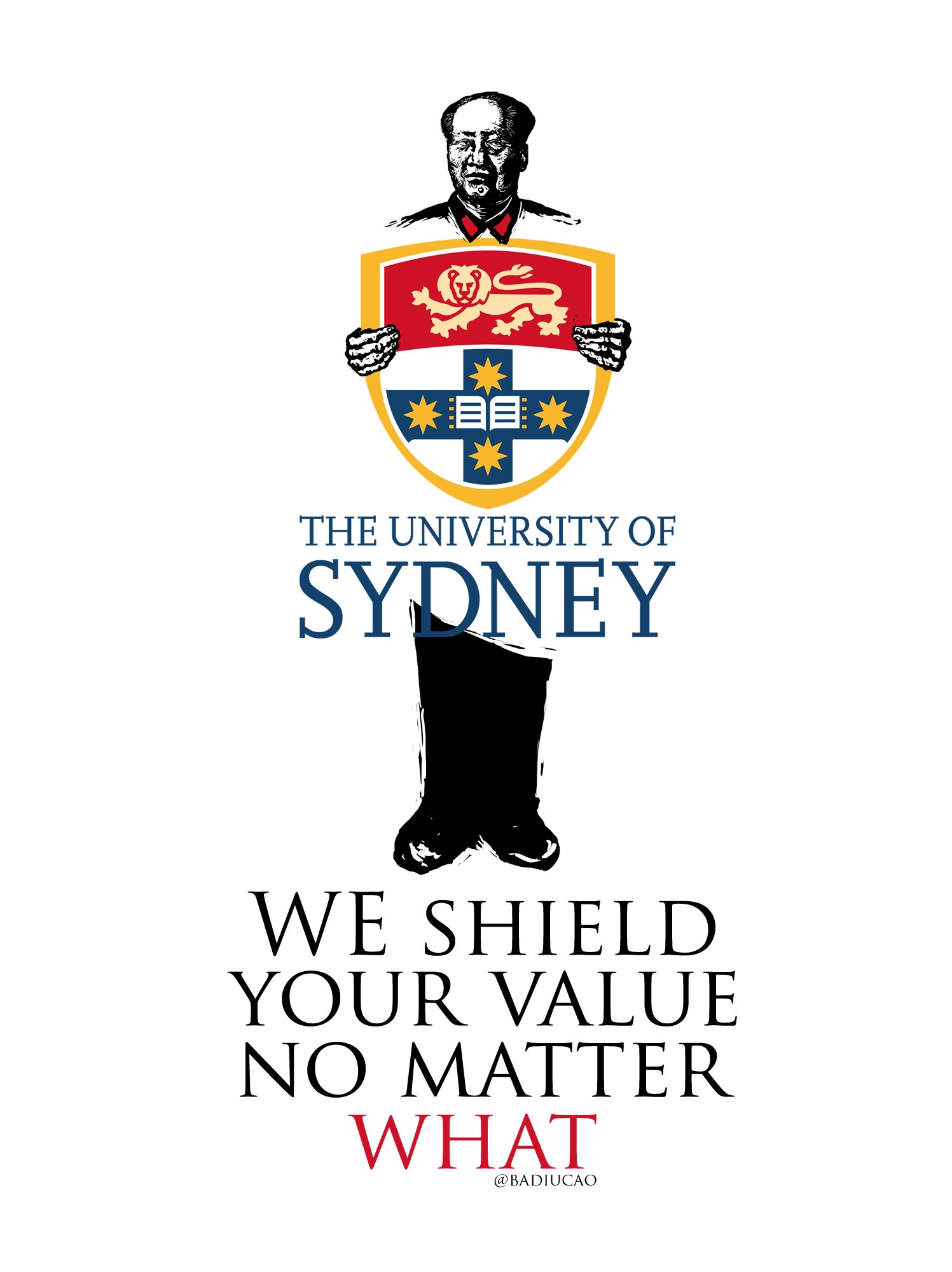

Last week, Curtin University, an Australian institution that employs one of the authors of the study, said it had found “significant concerns” with the paper.

Science journals are now setting different standards.

In February, a journal called Frontiers in Genetics rejected a paper that was based on findings from the DNA of more than 600 Uighurs.

Science journals are now setting different standards.

In February, a journal called Frontiers in Genetics rejected a paper that was based on findings from the DNA of more than 600 Uighurs.

Some of its editors cited China’s treatment of Uighurs, people familiar with the deliberations said.

The paper was instead accepted by Human Genetics, a journal owned by Springer Nature, and published in April.

The paper was instead accepted by Human Genetics, a journal owned by Springer Nature, and published in April.

Philip Campbell, the editor of Springer Nature, said this week that Human Genetics would add an editorial note to the study saying that concerns had been raised regarding informed consent.

Springer Nature will also bolster guidelines across its journals and is contacting their editors to “request that they exercise an extra level of scrutiny and care in handling papers where there is a potential that consent was not informed or freely given,” it said in an email.

The paper published in Human Genetics was a subject of a Times article on Tuesday that raised questions about whether the Uighurs had contributed their blood samples willingly.

The paper published in Human Genetics was a subject of a Times article on Tuesday that raised questions about whether the Uighurs had contributed their blood samples willingly.

Those Uighurs lived in Tumxuk, a city in East Turkestan that is ringed by paramilitary forces and is home to two internment camps.

Scientists like Dr. Moreau are not calling for a blanket ban on Chinese research into the genetics of China’s ethnic minorities.

Scientists like Dr. Moreau are not calling for a blanket ban on Chinese research into the genetics of China’s ethnic minorities.

He drew a distinction between fields like medicine, where research is aimed at treating people, and forensics, which involves matters of criminal justice.

But Dr. Moreau found that recent genetic forensics research from China focused overwhelmingly on ethnic minorities and was increasingly driven by Chinese security agencies.

Of 529 studies in the field published between 2011 and 2018, he found, about half had a co-author from the police, military or judiciary.

But Dr. Moreau found that recent genetic forensics research from China focused overwhelmingly on ethnic minorities and was increasingly driven by Chinese security agencies.

Of 529 studies in the field published between 2011 and 2018, he found, about half had a co-author from the police, military or judiciary.

He also found that Tibetans were over 40 times more frequently studied than China’s ethnic Han majority, and that the Uighur population was 30 times more intensely studied than the Han.

.

A paper from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers in 2014 looked at “Learning race from a face.”

Over the past eight years, he wrote, three leading forensic genetics journals — one published by Springer Nature and two by Elsevier — have published 40 articles co-authored by members of the Chinese police that describe the DNA profiling of Tibetans and Muslim minorities.

Tom Reller, a spokesman for Elsevier, said the company was in the process of producing more comprehensive guidelines for the publication of genetic data.

.

A paper from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers in 2014 looked at “Learning race from a face.”

Over the past eight years, he wrote, three leading forensic genetics journals — one published by Springer Nature and two by Elsevier — have published 40 articles co-authored by members of the Chinese police that describe the DNA profiling of Tibetans and Muslim minorities.

Tom Reller, a spokesman for Elsevier, said the company was in the process of producing more comprehensive guidelines for the publication of genetic data.

But he added that the journals “are unable to control the potential misuse of population data articles” by third parties.

The principle of informed consent has been a scientific mainstay after forced experiments on inmates in Nazi death camps came to light.

The principle of informed consent has been a scientific mainstay after forced experiments on inmates in Nazi death camps came to light.

To verify that those standards are followed, academic journals and other outlets depend heavily on ethical review committees at individual institutions.

Bioethicists say that arrangement can break down when an authoritarian state is involved.

Already, Chinese scientists are under scrutiny for publishing papers on organ transplantation without saying whether there was consent.

In its own review of more than 100 papers published by Chinese scientists in international journals on biometrics and computer science, The Times found a number of examples of what appeared to be inadequate consent from study participants or no consent at all.

In its own review of more than 100 papers published by Chinese scientists in international journals on biometrics and computer science, The Times found a number of examples of what appeared to be inadequate consent from study participants or no consent at all.

Those concerns have also dogged facial recognition research in the United States.

One 2016 facial recognition paper published by Springer International was based on 137,395 photos of Uighurs, which the scientists said were from identification photos and surveillance cameras at railway stations and shopping malls.

One 2016 facial recognition paper published by Springer International was based on 137,395 photos of Uighurs, which the scientists said were from identification photos and surveillance cameras at railway stations and shopping malls.

The paper does not mention consent.

A 2018 study, focused on using traffic cameras to identify drivers by beard, uses surveillance footage without mentioning whether it got permission from the subjects.

A 2018 study, focused on using traffic cameras to identify drivers by beard, uses surveillance footage without mentioning whether it got permission from the subjects.

The paper was also published by Springer.

A second 2018 Springer article that analyzes Uighur cranial shape to determine gender was based on “whole skull CT scans” of 267 people, mostly Uighurs.

A second 2018 Springer article that analyzes Uighur cranial shape to determine gender was based on “whole skull CT scans” of 267 people, mostly Uighurs.

While the study said the subjects were “voluntary,” it made no mention of consent forms.

The latter two papers were part of a book published by Springer as part of a biometrics conference in East Turkestan’s capital, Urumqi, in August 2018, months after rights groups had documented the crackdown in the region.

The latter two papers were part of a book published by Springer as part of a biometrics conference in East Turkestan’s capital, Urumqi, in August 2018, months after rights groups had documented the crackdown in the region.

In a statement, Steven Inchcoombe, chief publishing officer of Springer Nature, said that conference organizers were responsible for editorial oversight of the conference proceedings.

But he added that the company would in the future strengthen its requirements of conference organizers and ensure that their proceedings also comply with Springer Nature’s editorial policies.

A 2018 study published by Springer, on identifying drivers by beard, used surveillance footage without mentioning whether it got permission.

Two papers assembled databases of facial expressions for different minority groups, including Tibetans, Uighurs and Hui, another Muslim minority.

A 2018 study published by Springer, on identifying drivers by beard, used surveillance footage without mentioning whether it got permission.

Two papers assembled databases of facial expressions for different minority groups, including Tibetans, Uighurs and Hui, another Muslim minority.

The papers were released in journals run by Wiley and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

Wiley said the paper “raises a number of questions that are currently being reviewed.”

It added that the paper was published on behalf of a partner, the International Union of Psychological Science, and referred further questions to it.

The engineers institute did not respond to an emailed request for comment.

The science world has been responding to the pressure.

The science world has been responding to the pressure.

Thermo Fisher, a maker of equipment for studying genetics, said in February that it would suspend sales to East Turkestan, though it will continue to sell to other parts of China.

Still, Dr. Moreau said, the issue initially received little traction among academia.

“If we don’t react in the community, we are going to get more and more into trouble,” he said.

“If we don’t react in the community, we are going to get more and more into trouble,” he said.

“The community has to take a major step and say: ‘This is not us.’”

Shuping Yang

Shuping Yang Sophie Richardson testifying.

Sophie Richardson testifying.

%2Fhttps%253A%252F%252Fblueprint-api-production.s3.amazonaws.com%252Fuploads%252Fcard%252Fimage%252F455690%252F6b565bb0-74f5-42d2-b35d-c3a644426ab6.jpg&resize=w704)