It’s possible to spend long stretches in China without so much as touching a banknote.

This makes the world’s second-largest economy an internet-enabled paradise, albeit with an important caveat.

Two weeks later, Pichai acknowledged the program.

But at a weekly all-staff meeting, he and Brin argued that Dragonfly was being overplayed by the media.

It was merely “exploratory,” Pichai said.

“Every year or so there’s a new kind of project to do something or other in China,” Brin told staff, according to a

transcript obtained by Bloomberg

Businessweek.

“We experiment with what it might look like.”

The mood inside the room was tense, and Google’s corporate message boards were instantly flooded with debate.

As the meeting continued, someone in the auditorium began leaking Brin’s and Pichai’s comments to

New York Times reporter

Kate Conger, who relayed them,

verbatim, on Twitter.

Suddenly, those tweets were projected on screens behind Brin.

A person shouted, “F--- the leaker!”

Brin, according to three people who witnessed the scene, seemed more alarmed by the leak than by the ensuing outburst.

If employees were going to talk to the press, he said, they would have to shut down the meeting.

Pichai changed the subject.

Five days later, on Aug. 21,

Jack Poulson, a Google senior researcher, submitted a resignation letter. “I cannot work at a company that will not internally or publicly clarify its ethical red lines,” he wrote. It was part of a wave of resignations that came in the days following the meeting.

Pichai dug in, and, according to people familiar with his thinking, he remains interested in launching Dragonfly, or something like it.

“It’s a wonderful, innovative market,” he

said at a conference in October, referring to China’s 800 million internet users.

Google’s Chinese search engine in 2006.

Google’s Chinese search engine in 2006.

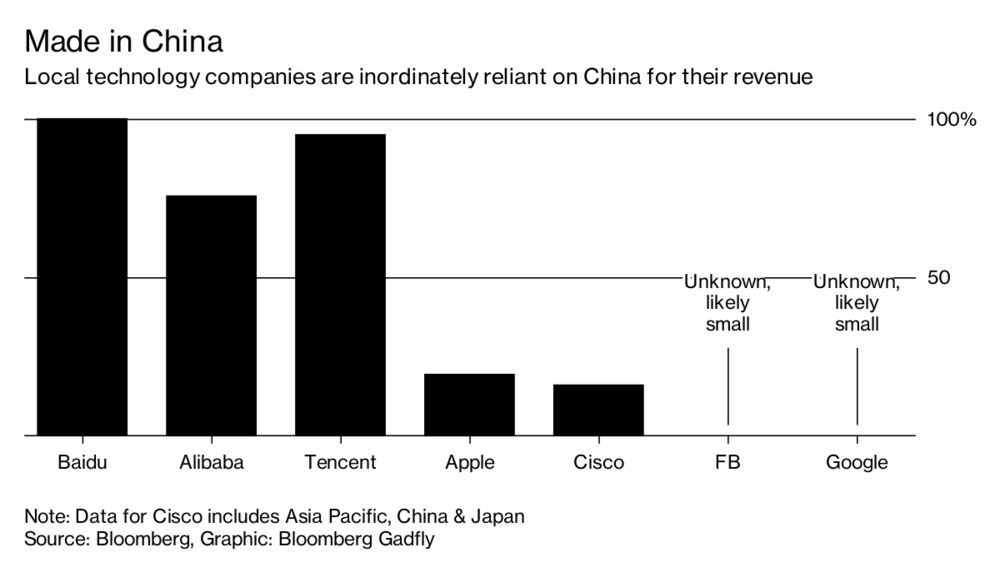

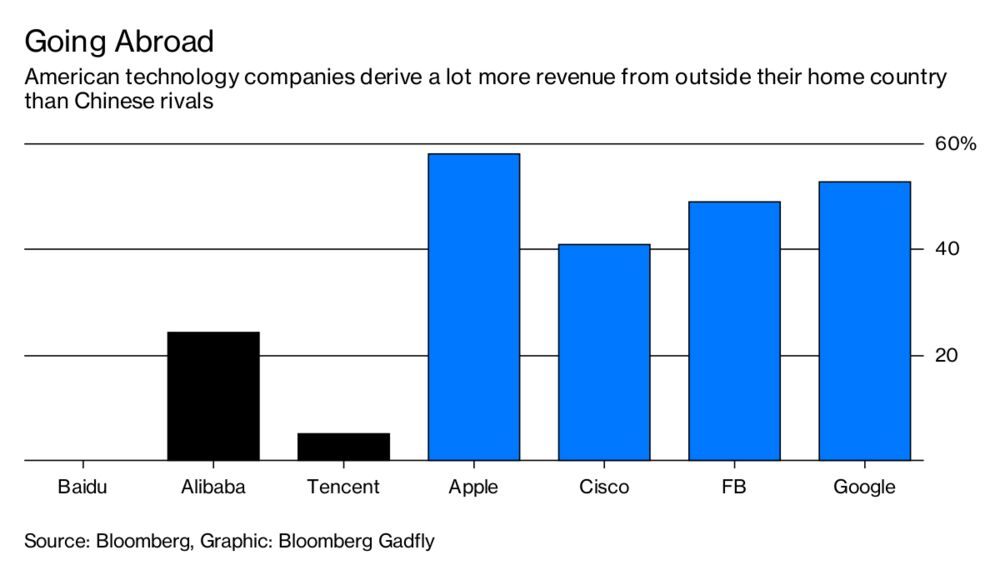

The Valley’s tech giants tend to share his enthusiasm.

China’s consumers have embraced mobile phones,

digital payments, and streaming media in unprecedented numbers.

But Google employees worry that

Pichai is being willfully blind to the compromises China is asking the company to make.

The search giant grew gigantic “on the premise that they were somehow exceptions to the corporate norm,” says a Google employee, who, like many interviewed for this story, declined to be identified discussing sensitive matters.

“They have immense and, in some ways, unprecedented power. And the checks on this power are currently scarce.”

These fears found expression in a memo Downey circulated privately in late August.

He was known within Google as an idealist; after

Edward Snowden revealed that the National Security Agency had intercepted Google data, Downey railed against the program as an example of government overreach.

“F--- these guys,” he wrote about the NSA in a

widely shared Google Plus post.

In his new memo, Downey contrasted the altruistic ambitions of Google’s founders with what he presented as a

company now motivated by a desire for growth and profit.

Dragonfly, Downey pointed out, also happens to be the name of Brin’s megayacht. (A Google spokesman says this is a coincidence.)

“Google has changed,” Downey wrote.

Google declined to make Brin, Pichai, or any other executive available for an interview.

The company, which is also under fire for its handling of

sexual harassment complaints,

has yet to explain how search in China would square with its long-standing pledge to protect the privacy of its users.

Privately, executives have argued that if Google wants to continue growing globally, it will have to work with governments that don’t share its values.

Interviews with more than 18 current and former employees suggest the company’s predicament resulted in part from failing to learn from mistakes that played out a decade earlier, when it first confronted the realities of China’s economic and political might.

This history is known to many at Google’s headquarters in Mountain View, Calif., but mostly unknown outside of it.

In an interview in September, Downey, 42, elaborates.

“There’s this Utopian idea: Technology will come in, and people will take these tools, change their government, and get their freedom,” he says.

“We tried that experiment, and it didn’t work.”

Downey, photographed at his home in Mountain View.

Downey, photographed at his home in Mountain View.

Downey grew up in Bayou La Batre, a small town in southern Alabama, where he fell in love with the internet.

“It was just an unalloyed good,” he says of his first experience dialing up on a 2,400-baud modem he bought by mowing lawns one summer in high school.

When Google arrived in 1998, he saw it as a force for freedom and “a miracle.”

Then in 2004, something miraculous happened: Downey, who’d earned a degree from Tulane University, landed a job at the company writing code for the back-end systems of its search engine.

At the time, Google’s founders were struggling to square the ideals of the early web with the realities of running a for-profit company.

As early as 2002, Brin, who was born in the Soviet Union and has made no secret of his dislike of authoritarian regimes, was consulting experts on Chinese censorship.

“He gave me the impression that he was genuinely thinking about the issue of China and human rights,” says

Xiao Qiang, a prominent China-born human-rights activist who now lives in the U.S. Xiao suggested to Brin that the search engine would be a liberalizing force there.

After months of planning, Brin and the executive team devised a strategy to deal with the requirements of China’s censors.

A local partner would filter results, and Google would store user data on servers outside the country. On the bottom of each page of censored results, coders added a disclosure in small type that informed web surfers that certain sites had been withheld, which was seen as a sort of middle finger to the People’s Republic.

“Let me tell you,” says Downey, who contributed code to the effort, “the Chinese government was not happy about that disclaimer.”

Employees nicknamed the service Dragon Index.

When Brin went to Xiao with the plans in 2006, the activist gave his blessing.

“It’s better than not being there,” he said at the time.

Brin and many Google employees agreed.

At the time, the web looked like a democratizing force.

Many assumed that Google, even if handicapped, could open the floodgates.

“People really believed that providing some information was better than none,” Downey recalls.

During a debate on an internal mailing list, an employee argued that Dragon Index was “not only not evil, but one of the most good things we’ve done.”

The message was published last month on Twitter by

Vijay Boyapati, a former Google engineer.

One of the things he found most “disturbing” in retrospect, he wrote, was “the willingness of my former colleagues to not only comply with the censorship, but with their enthusiasm in rationalizing it.”

Almost as soon as Google started the service, demands from Beijing’s censors escalated.

In 2006 the search engine had to filter out just a few hundred terms, Downey says; by the Beijing Olympics, two years later, the number had climbed to 10,000.

In addition to its web search engine in China, Google also created a search service for news articles, which was subject to even more stringent rules.

Chinese officials required the company to restrict Google News results to Chinese websites only and to suppress several large sections—World, Nation, and Business, according to Boyapati.

The government asked Google to commit to pull any article that offended the censors within 15 minutes.

Unlike search pages, blacklisted News results didn’t include a disclaimer.

“No one in the company knew this,” Boyapati says.

“It just sort of came down from management.”

Then in December 2009, Google’s security team discovered something far more troubling.

Hackers had somehow tapped the system the company used to store people’s passwords.

The hackers also injected malicious code onto staffers’ computers in Beijing.

According to company sources and an account in

Steven Levy’s book

In the Plex, Google traced the attackers to China and quickly discovered

their aim: to spy on email accounts maintained by dissidents.

Marty Lev, Google’s security chief at the time, was forced to drive to Stanford University to rescue the laptop of one victim, a student who led pro-Tibet protests.

Soon after, Google learned that

the hackers had somehow also stumbled onto the source code for google.com, the company’s version of Coca-Cola’s secret formula.

Immediately, Google sequestered a team in a top-secret “war building,” a participant recalls.

This person says the team was warned that their work could be controversial and would probably mean China would never grant them a visa again.

Like everything at Google, the building had a code name: Helm’s Deep, after the fortress in

J.R.R. Tolkien’s books in which humankind, pursued by Sauron’s all-seeing eye, hides from the forces of evil.

Inside Helm’s Deep, the conversation turned to how to respond to China’s aggression.

Eric Schmidt, then CEO, argued that Google could wield more influence by staying in China.

Brin led the other flank, according to five people involved in the discussions.

Those people recall Brin as the most animated, raging less about the source code theft than about a state coming after Google users.

“Sergey was pissed off,” a former executive says.

Brin won out.

On Jan. 12, Google announced it was ending search in China.

“Our objection is to those forces of totalitarianism,” Brin told the

New York Times.

In Beijing people laid flowers at Google’s campus in a mix of grief and mockery over its departure. Reports surfaced that police had banned the practice, and the phrase “illegal flower throwing” quickly became a subversive joke on the Chinese web.

Downey and some co-workers made T-shirts bearing the phrase, another middle finger to the Politburo.

Outside Google’s China headquarters in Beijing on Jan. 13, 2010, shortly after the company announced it was pulling out of China.

Outside Google’s China headquarters in Beijing on Jan. 13, 2010, shortly after the company announced it was pulling out of China.

Despite this experience, Google never really gave up on China.

The company tried many times, often fruitlessly, to tiptoe back.

A former Asia staffer says there was a running joke that the company was always one quarter away from some launch in China.

Among the key players was Pichai, who spent years running Android, Google’s free mobile operating system, before being elevated to CEO in 2015.

Around 2013, according to a former product manager, Pichai stopped a presentation, insisting that the Android numbers were incorrect because, as was customary at the time, they didn’t include usage of Android in China.

“It’s the biggest country in the world,” Pichai said, according to the ex-employee. “It doesn’t make sense not to think about it.”

During Pichai’s tenure, Google tried to bring its Android app store to China, just as Apple offers one to serve iPhone owners there.

Managers, including Pichai, felt the app store could be a side door into the country—hence the effort’s internal name, Sidewinder—according to two people who worked on it.

Beijing never rejected the proposal outright, but it never greenlighted it, either, these people say.

Other paths also dead-ended.

A former manager recalls a Kafkaesque scene when Google applied for a license to create digital maps of China’s roads.

A government official listened to the pitch and assented, with one condition: Google must avoid politically sensitive areas.

“Sure, where are those?” the company rep asked.

“Oh, no,” the official said, “we can’t tell you that.”

Today, internet users in China can search Google only with a virtual private network, or VPN, which gets around the Great Firewall via cloud servers. (China

banned “unauthorized” VPNs in March; some still seem to work.)

And more modest Google offerings have made it past regulators.

Last year the company launched its translation app in China with regulators’ blessing.

This year it offered Files Go, a file-management app for Android phones, and a doodling game, Guess My Sketch, available on WeChat.

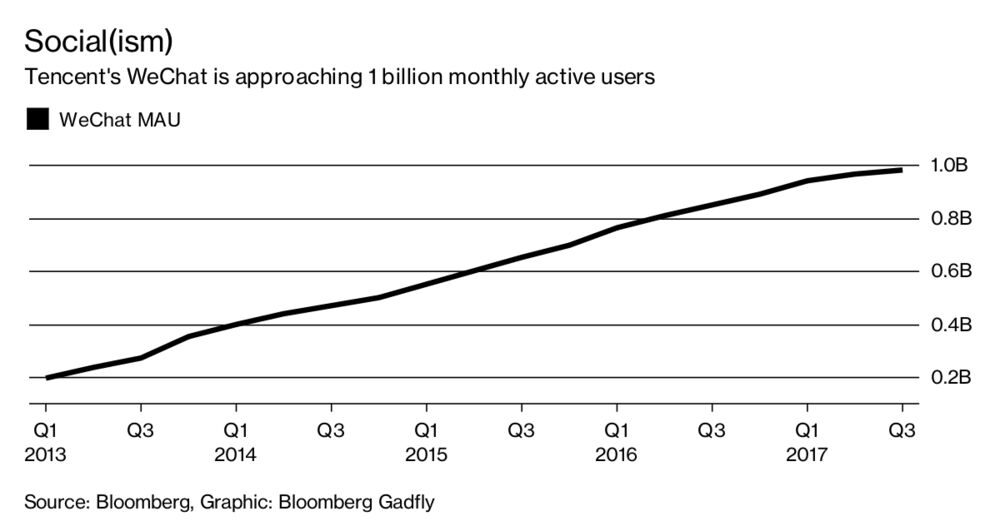

Pichai confers regularly with

Martin Lau, president of WeChat parent

Tencent Holdings Ltd., according to a Chinese tech veteran who knows both.

Part of Pichai’s interest in China stems from his focus on artificial intelligence.

Google is widely regarded as the world leader in the field, but Chinese dictator

Xi Jinping has designated

AI a priority as part of an ambitious industrial policy.

Google responded by opening an AI lab in Beijing in January to try to take advantage of China’s talent pool in the field.

And in September the company sponsored a government-organized AI conference in Shanghai.

The event’s title: “AI for everyone.”

China’s embrace of AI could eventually support the country’s efforts to control speech on the web.

A 2017 cybersecurity law mandates that companies host Chinese customer data on servers in the country and requires users to sign up for online services using real names and mobile numbers.

That’s why prototypes of Dragonfly linked searches to phones.

Poulson, the researcher who resigned, says this was hidden from some on Google’s privacy review team, which he cited as a “catastrophic failure.”

“It feels like a war on truth,” Downey says.

Outside experts have raised similar concerns.

“Authorities can access the user data when they see fit,” says

Lokman Tsui, a former policy manager for Google in Hong Kong.

“It’s impossible for Google to operate search in China without violating widely recognized human rights.”

Tsui, now a journalism professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, was among those who signed a public letter in August asking the company to reaffirm its 2010 commitment not to censor its search engine.

So did Xiao, who now says he’d advise Google’s founders to stay out:

“China has no boundaries between the state and private companies. If you go there, you must be part of digital totalitarianism.”

But nobody at Google asked Xiao for his opinion this time; he can’t recall when he last spoke to Brin.

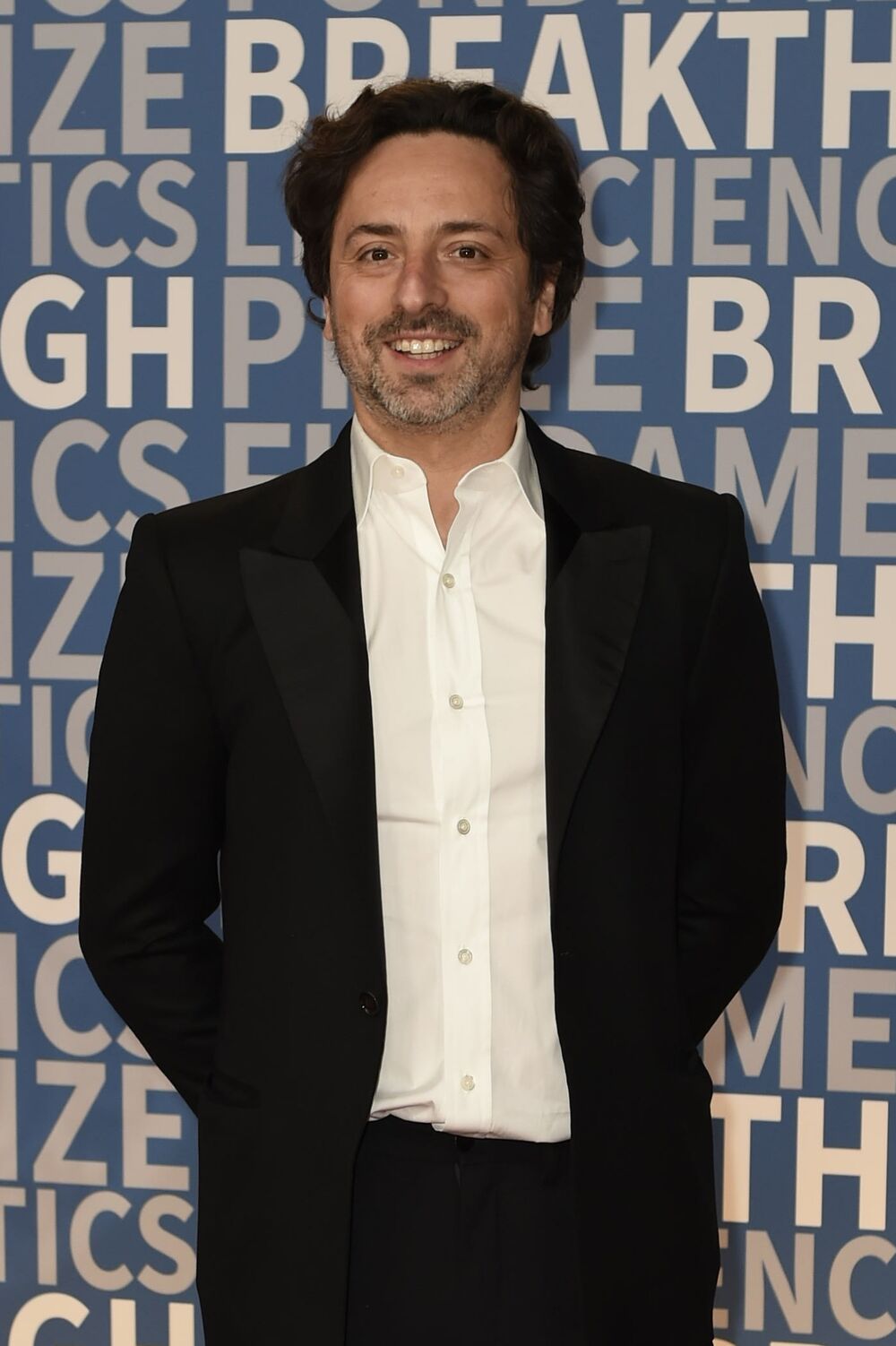

Brin at the 2018 Breakthrough Prize award ceremony in Mountain View.

Brin at the 2018 Breakthrough Prize award ceremony in Mountain View.

After the contentious August staff meeting, Google publicly defended its China plans, in part by criticizing

Baidu, the country’s dominant search engine.

“Today people either get fake cancer treatments or they get valuable information,” Pichai said in October at a Wired conference in San Francisco.

The reference was probably lost on most of the audience, but it would have been well-known in China, where a Baidu search ad for an experimental medical treatment was blamed for giving misleading information to a young cancer patient, who later died. (Baidu tightened restrictions on medical ads in response to the incident.)

To ease tensions, Google has been holding informal meetings with staff opposed to Dragonfly to bring skeptics around.

Supporters argue that Google, even in limited form, will be an improvement over Chinese search engines and that the compromises the company is being asked to make have been made by other American tech giants.

Poulson says that at a staff meeting, Brin justified Dragonfly by pointing out that no one had complained about Sidewinder, the app store project.

According to someone close to him,

Brin’s about-face on China came as a result of traveling to the country at least three times since 2016, during which he met with Google staff, tinkered with Chinese apps, and on one occasion met with a champion Go player.

But many at Google don’t seem convinced.

One participant in the meetings says the C-suite seems paralyzed, caught between whatever fallout will come with proceeding in China and the costs of ignoring an enormous business opportunity.

Downey sees no room for moral ambiguity.

“Google has no principled excuse left for doing this,” he wrote in August.

His essay ended with the most damning of critiques for a company that’s always seen itself as above concerns about revenue and profit.

“Google,” Downey wrote, “is acting like a traditional company.”