Last month there were 300,000 doctor’s visits in Hong Kong linked to smog wafting over from mainland China. But in a busy town obsessed with money, will it take a direct economic hit to wake people to the danger?

By Benjamin Haas in Hong Kong

Much of Hong Kong’s pollution comes across from mainland China.

At the age of three, Margaux Giraudon developed something akin to a smoker’s cough.

Thereafter, she became all too familiar with the inside of her doctor’s office in

Hong Kong.

For years, her father

Nicolas Giraudon was told the same thing by doctors: “Your daughter is sensitive to changes in the weather.”

Eventually she grew so ill that she was hooked up to breathing machines in the hospital for three days, inhaling medicine delivered in a mist.

At that point, Giraudon decided it was time for the family to return to his native France.

“She was scared – she didn’t know what was going on, and she saw the look on our faces,” Giraudon recalls.

“Her mother and I were completely shocked. When you have children, you want the best for them; you want to protect them as much as possible.”

For Giraudon, those three days transformed

Hong Kong from an international city bustling with excitement and opportunity into a

death trap that was slowly poisoning his family.

Born on the island, Margaux had developed

asthmatic bronchitis, which caused her lung capacity to fall by nearly a third compared to other children her age.

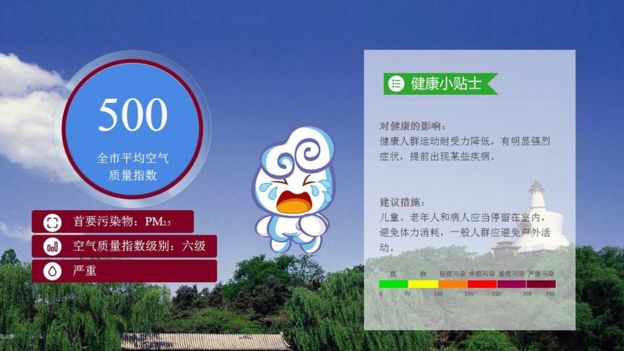

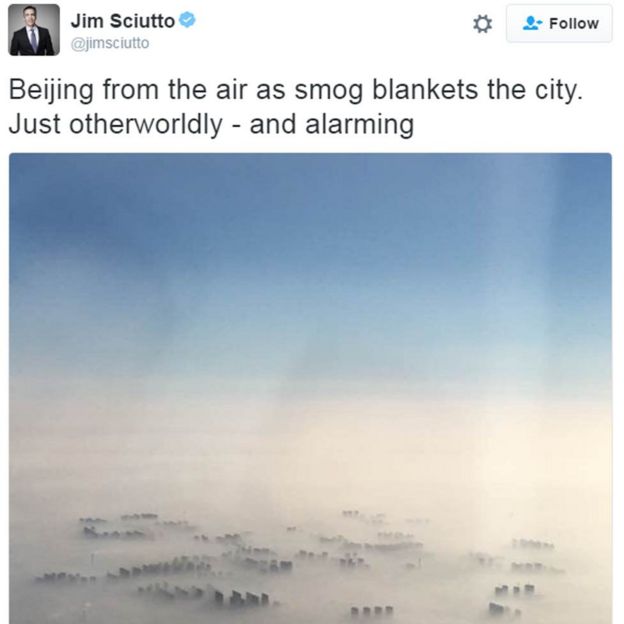

While Hong Kong’s air pollution rarely commands the attention of the toxic cloud that frequently covers northern

China, dubbed the

“airpocalypse”, the air is anything but clean here.

Levels of

cancer-causing pollutants have exceeded World Health Organization standards for over 15 years, rising to more than five times acceptable levels at its peak.

As far back as 2013, the government called air pollution the

“greatest daily health risk to the people of Hong Kong”.

Despite awareness of the dangers, this notoriously pro-business city has moved at a glacial pace in tackling the problem, commissioning study after study but taking little concrete action.

The fast-paced business world is what originally brought Giraudon to Hong Kong in 2009.

In the six years before his daughter became sick, he didn’t experience any noticeable effects from air pollution.

The 42-year-old media executive went hiking in the mountains around the city and jogged all over his new home, realising a lifelong dream of working in Asia.

He didn’t buy air purifiers, dismissing the costly machines as a marketing trick.

Margaux Giraudon developed asthmatic bronchitis while living in Hong Kong. Photograph: Nicolas Giraudon

After his daughter’s hospital stay, however, Giraudon transformed completely.

He bought a device to measure air pollution and became obsessed.

Every room in his house was fitted with an expensive air purifier, and he checked the air quality constantly.

“My flat in Hong Kong felt like living in a spaceship,” he says.

“I was measuring the level of pollution 24 hours a day, measuring humidity to combat mould, to make sure everything was within acceptable levels.”

Giraudon would hear his neighbour’s children coughing at night, and knew they didn’t have air filters.

“I became the guy nobody invited for dinner,” he recalls with a sigh.

“Especially the newcomers, who were all really excited to arrive in Hong Kong – and then I would come with my readings and warnings. People didn’t want to hear about it.”

Giraudon began taking his testing equipment to his daughter’s school and was shocked to discover the air was terrible.

But he also found another group of people who did not want to hear about the problem: school officials.

He launched a campaign to clean the air there, and was met with resistance at every turn.

The city is notorious for capitalism run amok, and the authorities have long preferred the status quo or very slow change – a perpetual complaint among activists.

In a sign that ignorance about the health effects of pollution extends to the very top, one former chief executive

famously said: “Life expectancy [in Hong Kong] is the highest on earth, higher than that in Japan these days. It must be our air.”

The year he made that statement, pollution levels were more than four times WHO recommendations.

Hong Kong is one of the most densely populated places in the world.

The source of the smog

While equipping every room of a school or home with filters can clean the air, it’s only a plaster over the larger problem: tackling pollution at the source.

Emissions from cars and container ships are some of the largest contributors to Hong Kong’s smog. Old diesel vehicles still number in the tens of thousands, and

ships sailing into the city’s port, one of the busiest in the world, are allowed to burn high sulphur fuel right up until they dock.

Power plants, meanwhile, rely almost entirely on fossil fuel, with

coal supplying

52% of the city’s energy.

Much of Hong Kong’s pollution, however, wafts across the border from China.

In winter, when the wind direction tends to blow more pollutants towards Hong Kong, as much as 77% of dust in the air comes from China.

Hong Kong has signed a series of agreements with Guangdong province directly to the north – but they are unenforceable, stymying efforts by the local government and activists to have a meaningful impact.

In the meantime, the health impact on Hong Kong’s population is severe.

There were more than 1,600 premature deaths last year because of air pollution, according to Hong Kong University’s school of public health.

A clean, blue-skied billboard against the city’s polluted skyline.

With a government that is scarcely accountable to Hong Kong residents, environmental campaigners are fighting an uphill battle to contain even local sources of pollution.

The city’s leader, known as the chief executive, is elected by a 1,200-strong committee made up of elites, where

China has considerable sway over the votes.

Only half the seats in the legislature are directly elected, with the remaining lawmakers returned by professional organisations that overwhelmingly support Beijing.

Tanya Chan, chairman of the environmental affairs panel in the city’s legislature, recalls constituents clamouring for the government to clean up the air, fearing for the health of their children.

“The government can try harder and they should push harder,” she says.

“We need to be improving fuel standards and expanding the use of electric vehicles.”

Chan is in favour of introducing congestion pricing to some of the city’s most clogged districts, but lawmakers are hamstrung by a political system where all power related to government spending or levies requires approval from the chief executive.

“He is only accountable to a small election committee, where most come from business sectors,” Chan says. “We have no choice but to breathe this air.”

The city’s air quality standards (government targets for clean air) remained unchanged for 27 years before eventually being updated in 2014.

But they still fall short of WHO guidelines.

“We need to improve our air quality standard to catch up with international standards,” Chan adds. “That process has been a bit slow and I hope the government will do more, especially for the PM2.5s.”

The Environmental Bureau

only began publicising Hong Kong’s PM2.5 figures in 2012, nearly seven years after it began monitoring the harmful pollutant, and only after Beijing began publishing the same information.

But locals are increasingly concerned, and hungry for information.

Hong Kong’s air pollution caused more than 1,600 premature deaths last year.

The activists

On a recent evening, tucked away on the second floor of a sleepy cafe, about two dozen people gather to receive a crash course in Hong Kong’s pollution situation.

The mostly young crowd are a mix of office workers, salesmen and artists, all united by their previous ignorance of the dangers in the air and their anger at the officials they say kept them in the dark.

Leading the meeting is

Patrick Fung, chief executive of the

Hong Kong Clean Air Network.

The 31-year-old has become the face of the fight for better air quality in the city, and while he’s often dressed in tailored shirts and trousers to ensure his message is taken seriously, his shoulder-length hair, goatee and glasses evoke an image of environmental activists from years past.

In many ways the former advertising executive lives by the phrase: “There’s no such thing as bad publicity,” taking any opportunity to counter the narrative that dirty air is a fact of life.

“I’m just advertising something else now: cleaner air,” Fung says.

“It’s the most challenging product to sell: everyone wants it but it’s not just something you buy, some sacrifices need to be made.”

On the most basic level, Fung and his fellow campaigners want the government to update its air quality targets.

Narrow streets surrounded by high-rises have created “street canyons”, which can trap pollutants between buildings.

Fung’s group advocates for large swaths of the city’s main thoroughfares to be turned over to pedestrians, similar to

New York’s Times Square or plans for

Oxford Street in London.

Cindy Wong listens to Fung’s speech with rapt attention, bombarded with information she had never heard before.

“People in Hong Kong spend all their time worrying: prices are expensive, rent is high, salaries are low, so no one has time to care about pollution,” she says after the meeting.

“The government should have a strict policy to control pollution; the government should lead and people will follow.”

Patrick Fung: ‘[Clean air] should be a basic right.’

“The air seems much better in foreign countries, in Europe,” Wong adds.

Although she’s never been, she often watched with envy as travel programs highlighted tree-lined streets and plentiful gardens in cities abroad.

“A lot of Hong Kongers know about the poor air quality, but they feel powerless,” Fung says.

“It’s an issue of justice – this should be a basic right.”

After five years heading the environmental NGO, he says he can tell the air quality by his nose alone. “Everyone in this office can tell just by the smell of the air.”

Ignoring the problem

The vast majority of Hong Kong people don’t have air purifiers, and those that do tend to be wealthier and better educated, according to Peter Brar, manager at air quality testing company Renaud Air, which also sells filters.

He estimates about half of all expats have at least one air filter in their homes.

“A lot of the local people who’ve never had an opportunity to live abroad don’t know any better,” Brar says.

“They think going to the doctor and getting sick three times a year is normal; it’s not normal.”

Although many in Hong Kong may not be aware of the hazards of dirty air, the government has over a decade of data illustrating the problem – but it has been slow to act.

“A lot of the bureaucrats don’t want to be blamed for something,” Brar says.

“They just try to keep ignoring it and ignoring it as long as possible – and saving money, saving money until they have to do something.

“Hong Kong is a very pro-business environment,” he adds.

“

The government does know the air quality is really bad – but they try to hide the problem.”

In a town obsessed with money, the fact that

air pollution is estimated to have caused HK$20.bn (£2.2bn) worth of economic losses in 2016 may change more minds.

Brar points to a system where buildings in Hong Kong can apply for

a clean air certificate from the government – but the process only tests for PM10, particulate matter akin to dust or pollen, entirely ignoring the smaller, more harmful PM2.5.

He says companies that sell air purifiers frequently meet resistance from schools and business, with executives either in denial or unwilling to spend the money required to provide clean air.

When Giraudon wanted to present a professional report at his daughter’s school, Brar offered to test the air quality for free, but was also rebuffed by school officials.

Other schools have been more receptive – particularly international schools that have more money compared to government-run institutions.

Giraudon, however, has left behind his battle for classroom purifiers in favour of a suburb of Annecy, a small French city that has the reputation of having the cleanest lake in Europe.

Having arrived last December, Giraudon reports that his daughter Margaux already seems to be doing better.

Frequently sick in Hong Kong, she has yet to fall ill, is coughing less and no longer needs to carry an inhaler.

After eight years of living in Hong Kong, Giraudon admits he misses the excitement, opportunities and low taxes, which max out at 15% rather than France’s 45%.

“But I prefer to pay tax than to kill my children,” he says.