BY BETHANY ALLEN-EBRAHIMIAN

A scene from "Abominable" taken in a theater and shared by Vietnamese media.

Hollywood’s China reckoning has come.

But unlike the NBA’s recent China debacle, this time it’s not the United States but China’s nearest neighbors who’ve had enough.

Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia have all expressed outrage at a map of China that flickers across the screen in a new film released in late September.

Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia have all expressed outrage at a map of China that flickers across the screen in a new film released in late September.

The animated film, Abominable, is a joint production of DreamWorks and Pearl Studios, which is based in Shanghai.

The map includes China’s infamous “nine-dash line”—the vague, ambiguously marked demarcation line for its territorial claim over most of the Vietnam East Sea.

The dispute points to a new problem for Hollywood as studios move closer to Beijing’s positions. Silence on China is nothing new—but positively pushing the Chinese government’s view of the world is.

Hollywood’s traditional self-censorship on China has market roots.

The dispute points to a new problem for Hollywood as studios move closer to Beijing’s positions. Silence on China is nothing new—but positively pushing the Chinese government’s view of the world is.

Hollywood’s traditional self-censorship on China has market roots.

China’s burgeoning market of movie-goers is expected to soon surpass the United States as the largest in the world.

China’s censors have wielded this power adroitly, mandating that production companies abide by the party’s bottom lines in order to earn one of the 34 coveted spots allotted to foreign films for distribution in China each year.

That has resulted in a deafening silence from Hollywood on the realities of Chinese Communist Party rule.

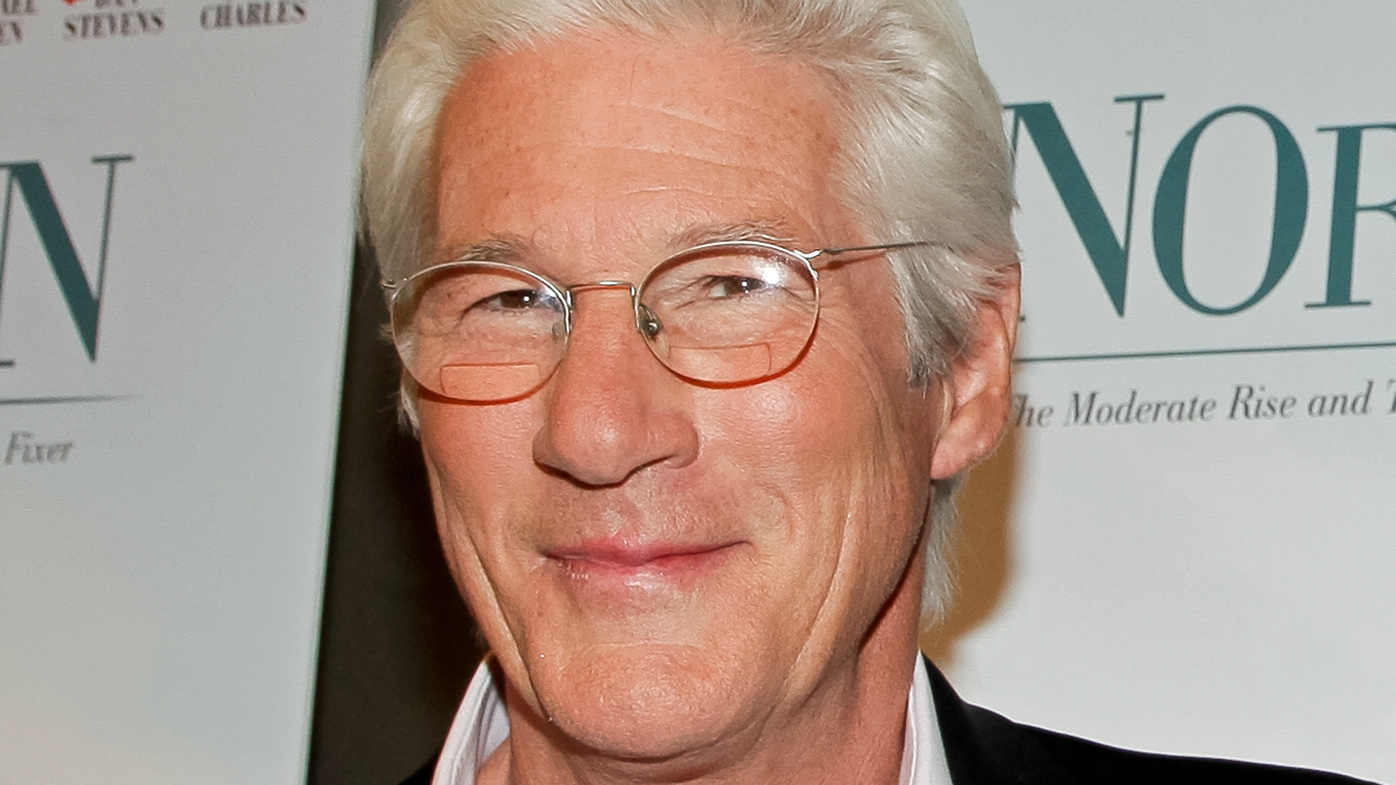

In the 1990s, several Hollywood films depicted oppression in Tibet, such as Seven Years in Tibet and Red Corner, and the Tibetan cause was popular among celebrities, most notably Richard Gere.

In the 1990s, several Hollywood films depicted oppression in Tibet, such as Seven Years in Tibet and Red Corner, and the Tibetan cause was popular among celebrities, most notably Richard Gere.

But there hasn’t been a major film sympathetic towards Tibet since Disney’s 1997 film Kundun, for which Disney CEO Michael Eisner flew to Beijing to apologize to the Chinese leadership.

Gere claims he has been frozen out of major films for his Tibet activism.

The 2013 zombie movie World War Z altered the location of the origin of the zombie outbreak from China to North Korea.

The 2016 film Doctor Strange changed the “Ancient One,” a Tibetan character in the original comic book series, to a white character played by Tilda Swinton.

In the past decade, no major film has portrayed China as a military foe of the United States.

Omitting offending plot lines and characters was once enough to satisfy Chinese censors.

Omitting offending plot lines and characters was once enough to satisfy Chinese censors.

But pressure has grown to include proactively positive depictions, particularly of Chinese science and military capabilities.

O. In the 2014 film Transformers: Age of Extinction, the Chinese military swoops in to save the day. One film critic described Age of Extinction as “a very patriotic film. It’s just Chinese patriotism on the screen, not American.”

O. In the 2014 film Transformers: Age of Extinction, the Chinese military swoops in to save the day. One film critic described Age of Extinction as “a very patriotic film. It’s just Chinese patriotism on the screen, not American.”

The payoff was enormous; Age of Extinction became the highest-grossing film of all time in China, raking in more than $300 million. (It no longer holds that record.)

China saved the day again in The Martian, the 2015 science fiction film starring Matt Damon.

NASA launches a special rocket carrying food for an astronaut stranded alone on Mars, but it explodes and NASA is out of options—until China’s space agency jumps into the plot out of nowhere, announcing it also has a special rocket it is willing to lend the Americans. (In fairness, the subplot was present in the original novel, not just introduced by the studio.)

The Martian brought in $95 million at the Chinese box office.

The growing phenomenon of U.S.-China joint movie productions has also resulted in a proliferation of mediocre films that cast China in a conspicuously positive light.

The growing phenomenon of U.S.-China joint movie productions has also resulted in a proliferation of mediocre films that cast China in a conspicuously positive light.

The 2018 B-grade shark flick The Meg, co-starring Chinese actor Li Bingbing, was one such coproduction.

It features an American billionaire who finances a futuristic ocean research station located, in a narrative non sequitur, off the coast of China, run by brilliant and heroic Chinese protagonists.

Abominable appears to be another.

Abominable appears to be another.

It features a young Chinese girl who discovers a yeti on her roof.

She decides to help the yeti find his way back home to the snowy mountains in the west, and they set off on a trek across China.

It has gotten middling reviews: One critic wrote that the film is “so distinctive pictorially, and so manifestly good-hearted, that it’s easy to forgive if not quite forget the ragged quality of its storyline.”

But the Chinese government’s heavy-handed film regulation department seems to have gone a bridge too far.

But the Chinese government’s heavy-handed film regulation department seems to have gone a bridge too far.

One scene in the movie includes a map of China on the young female protagonist’s wall.

Nine slim dashes trace a U-shape around the Vietnam East Sea, a resource-rich body of water with numerous land features also claimed by the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia, Taiwan, and Brunei.

China is the only country that recognizes this fallacious map.

China is the only country that recognizes this fallacious map.

The nine-dash line has no basis in international law, which does not recognize any country’s sovereignty over open waters.

In 2016, an international tribunal in the Hague also rejected China’s assertions of sovereignty over the Vietnam East Sea.

Beijing has never clarified the line’s legal definition or even its precise location, likely because to do so would open its vague claims up to further legal challenge.

These issues will come into sharper focus as Beijing begins to demand positive submission, not just omission.

These issues will come into sharper focus as Beijing begins to demand positive submission, not just omission.

China’s domestic film market has already shifted from censorship to forced inclusion of propaganda.

Last year, as part of a sweeping reorganization that saw many Chinese Communist Party bureaus absorb the purview of government departments, the party’s propaganda office took over regulation of the film industry.

The result has been even more heavy-handed censorship and more overtly patriotic content in films. Over the summer, six anticipated blockbusters were axed entirely, and China’s box office slumped.