By Marco Rubio

Demonstrators at Tamar Park in Hong Kong on Tuesday.

Beijing recently reinforced its People’s Liberation Army garrison in Hong Kong with thousands of troops and authorized a new wave of arrests to intimidate peaceful demonstrators.

In parallel, it blocked the Hong Kong government’s proposal to work out a compromise with the city’s massive and grassroots pro-democracy movement.

What began as a protest against an unjust extradition bill backed by China has now become a fight for Hong Kong’s autonomy and future.

What began as a protest against an unjust extradition bill backed by China has now become a fight for Hong Kong’s autonomy and future.

Yet what’s happening in Hong Kong is not simply China’s internal affair.

The United States and other responsible nations are not watching from the sidelines.

The extradition bill is only the latest example of China’s many broken promises to the Hong Kong people and the world.

The extradition bill is only the latest example of China’s many broken promises to the Hong Kong people and the world.

Most obviously, the Chinese Communist Party is preventing the city’s government from acting with the autonomy that Beijing had promised it in a legally binding 1984 international treaty with Britain, under Hong Kong’s Basic Law, and in China’s diplomatic outreach to the United States and other nations.

In 2014, Beijing also backed off its commitment to allow Hong Kong citizens to choose their city’s chief executive through universal suffrage, a provocation that sparked the city’s massive Umbrella Movement protests.

In 2014, Beijing also backed off its commitment to allow Hong Kong citizens to choose their city’s chief executive through universal suffrage, a provocation that sparked the city’s massive Umbrella Movement protests.

And in 2016 and 2017 , the High Court disqualified a total of six democratic lawmakers from their Legislative Council seats using a controversial interpretation of Hong Kong’s constitution.

Thirty years after People’s Liberation Army troops massacred reform activists and ordinary Chinese citizens on the way to Tiananmen Square, Beijing now appears poised to intervene overtly and aggressively in Hong Kong.

The paramilitary People’s Armed Police — built up in the aftermath of the Tiananmen massacre — has thousands of personnel and vehicles in Shenzhen, just across the boundary between mainland China and Hong Kong.

Chinese officials and state media have steadily escalated their warning rhetoric and outlined what they describe as the legal case for intervention based on “signs of terrorism.”

An unsigned editorial in Xinhua, a state-run news agency reflecting the institutional voice of the party center, claimed that Hong Kong is engaged in a “color revolution.”

The world ignores these warning signals at the peril of the Hong Kong people and the hundreds of thousands of foreigners — including roughly 85,000 U.S. citizens — living in the city.

China’s communists today are using the same messaging playbook that they have followed since they intervened in North Korea in 1950.

We were surprised then; we should be prepared now.

The United States and the international community must make clear to Chinese leaders and power brokers that their aggression toward Hong Kong risks swift, severe and lasting consequences.

In particular, the administration should make clear that the United States can respond flexibly and robustly in Hong Kong.

Our options are much more than just a “nuclear option” of ending Hong Kong’s special status under U.S. law.

The Hong Kong Policy Act, authored by Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) and enacted in 1992, allows the president to apply to Hong Kong those laws that address the People’s Republic of China.

The law’s power is selective and flexible, however, and not necessarily all-or-nothing for Hong Kong’s special status.

For example, the Tiananmen sanctions could be applied to target the city’s police force, which has collaborated with organized crime, instigated violence and now is torturing detained demonstrators.

Hong Kong’s special status — and therefore Beijing’s ability to exploit and benefit from it — depends on the city being treated as a separate customs area, on open international financial connections and on the Hong Kong dollar’s peg to the U.S. dollar.

The United States both administratively and diplomatically can constrain these conditions.

The administration also can impose sanctions against individual officials who have committed serious human rights abuses under the Global Magnitsky Act, which enables sanctions against foreign individuals or entities.

In addition, Congress should pass the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, a bill that I co-authored with Sens. Ben Cardin (D-Md.), James E. Risch (R-Idaho) and Robert Menendez (D-N.J.).

The bill, among other things, would mandate that officials in China and Hong Kong who have undermined the city’s autonomy are vulnerable to such sanctions.

The United States and other nations have options precisely because Beijing benefits from Hong Kong’s special status.

Indeed, the city has proved irreplaceable as a gateway for international finance, even as China attempts to build up a mainland alternative.

China’s leaders must either respect Hong Kong’s autonomy and rule of law or know that their escalating aggression will inexorably lead them to face swift, severe and lasting consequences from the United States and the world.

Today, that choice is theirs.

Thirty years after People’s Liberation Army troops massacred reform activists and ordinary Chinese citizens on the way to Tiananmen Square, Beijing now appears poised to intervene overtly and aggressively in Hong Kong.

The paramilitary People’s Armed Police — built up in the aftermath of the Tiananmen massacre — has thousands of personnel and vehicles in Shenzhen, just across the boundary between mainland China and Hong Kong.

Chinese officials and state media have steadily escalated their warning rhetoric and outlined what they describe as the legal case for intervention based on “signs of terrorism.”

An unsigned editorial in Xinhua, a state-run news agency reflecting the institutional voice of the party center, claimed that Hong Kong is engaged in a “color revolution.”

The world ignores these warning signals at the peril of the Hong Kong people and the hundreds of thousands of foreigners — including roughly 85,000 U.S. citizens — living in the city.

China’s communists today are using the same messaging playbook that they have followed since they intervened in North Korea in 1950.

We were surprised then; we should be prepared now.

The United States and the international community must make clear to Chinese leaders and power brokers that their aggression toward Hong Kong risks swift, severe and lasting consequences.

In particular, the administration should make clear that the United States can respond flexibly and robustly in Hong Kong.

Our options are much more than just a “nuclear option” of ending Hong Kong’s special status under U.S. law.

The Hong Kong Policy Act, authored by Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) and enacted in 1992, allows the president to apply to Hong Kong those laws that address the People’s Republic of China.

The law’s power is selective and flexible, however, and not necessarily all-or-nothing for Hong Kong’s special status.

For example, the Tiananmen sanctions could be applied to target the city’s police force, which has collaborated with organized crime, instigated violence and now is torturing detained demonstrators.

Hong Kong’s special status — and therefore Beijing’s ability to exploit and benefit from it — depends on the city being treated as a separate customs area, on open international financial connections and on the Hong Kong dollar’s peg to the U.S. dollar.

The United States both administratively and diplomatically can constrain these conditions.

The administration also can impose sanctions against individual officials who have committed serious human rights abuses under the Global Magnitsky Act, which enables sanctions against foreign individuals or entities.

In addition, Congress should pass the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, a bill that I co-authored with Sens. Ben Cardin (D-Md.), James E. Risch (R-Idaho) and Robert Menendez (D-N.J.).

The bill, among other things, would mandate that officials in China and Hong Kong who have undermined the city’s autonomy are vulnerable to such sanctions.

The United States and other nations have options precisely because Beijing benefits from Hong Kong’s special status.

Indeed, the city has proved irreplaceable as a gateway for international finance, even as China attempts to build up a mainland alternative.

China’s leaders must either respect Hong Kong’s autonomy and rule of law or know that their escalating aggression will inexorably lead them to face swift, severe and lasting consequences from the United States and the world.

Today, that choice is theirs.

Carrie Lam is seen on TV in Hong Kong announcing the formal withdrawal of the extradition bill that had provoked months of protests.

Carrie Lam is seen on TV in Hong Kong announcing the formal withdrawal of the extradition bill that had provoked months of protests.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/65133107/GettyImages_1163740420.0.jpg)

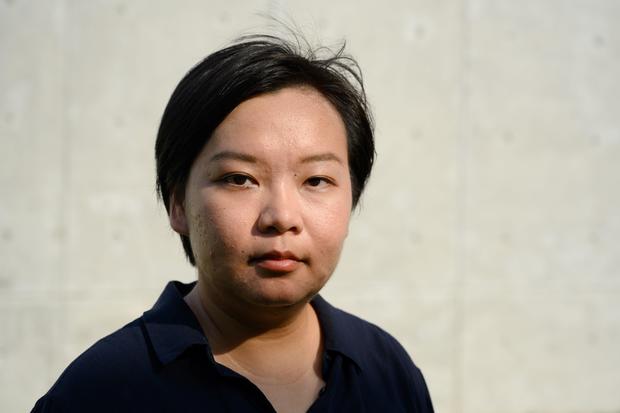

Bonnie Leung, vice convenor of the Civil Human Rights Front (CHRF), is seen during an interview in Hong Kong, August 20, 2019.

Bonnie Leung, vice convenor of the Civil Human Rights Front (CHRF), is seen during an interview in Hong Kong, August 20, 2019.

Protesters demonstrate against the extradition bill in July 2019

Protesters demonstrate against the extradition bill in July 2019

Protesters occupy a street demanding Hong Kong leader to step down after a rally against the now-suspended extradition bill outside of the Chief Executive Office on June 17 in Hong Kong.

Protesters occupy a street demanding Hong Kong leader to step down after a rally against the now-suspended extradition bill outside of the Chief Executive Office on June 17 in Hong Kong.