MISSISSAUGA, Ontario — Search for

Sheng Xue on Google in English and you will find the story of an award-winning writer who left China for Canada after the Tiananmen Square uprising and became one of the world’s leading advocates for Chinese democracy.

But that same search in Chinese comes up with a very different portrait: Sheng Xue is a fraud, a thief, a traitor and a serial philanderer.

Want proof?

It offers up salacious photos, like one seeming to show her kissing a man who is not her husband.

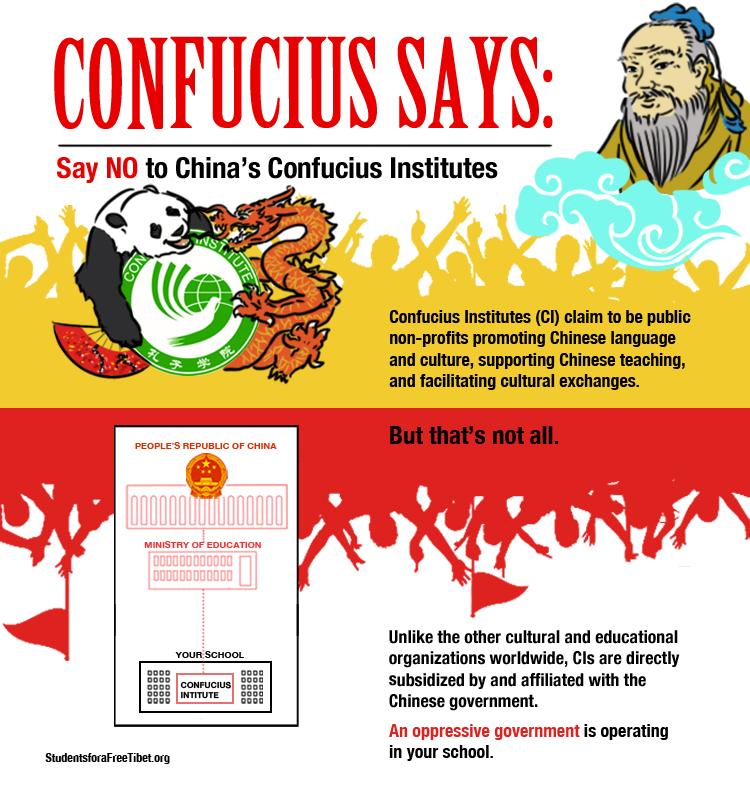

As China extends its influence around the globe, it has mastered the art of soft power,

establishing Confucius Institutes on Western college campuses and

funding ports and power plants in developing countries.

But building up is only one prong of the Chinese strategy.

The other is knocking down.

And few know this better than Sheng Xue.

For more than six years, the Chinese-Canadian activist has been the victim of a relentless campaign to discredit her by blog, Listserv, e-book and social media, which bears the markings of a coordinated attack by the Chinese Communist Party.

“

This is a textbook destabilization of the exile movement,” said

Nicholas Bequelin, Amnesty International’s regional director for East Asia.

“Since the early 1990s,” Mr. Bequelin said,

“China has understood the best way to neutralize this group and prevent them from essentially getting organized is to ensure they have no undisputed figurehead.”

Sheng Xue is the pen name for 57-year-old

Zang Xihong.

The attacks have left her name — and health — in tatters.

“I escaped Tiananmen Square in China,” she said one winter day sitting in the living room of her suburban bungalow outside Toronto.

“I thought I’d have a safe, happy life in Canada.”

But the Communist Party, she said, “was already here.”

The smears cannot be definitively linked to the Chinese government, experts say.

However in Canada, security experts have warned for years about the

growing influence of Beijing not only on Chinese expatriates but on the Canadian government itself.

In 2010, the head of Canada’s intelligence service

shocked the country by

declaring that

the Chinese Communist Party had agents of influence in local governments.

And in 2017, a confidential report prepared by the Canadian branch of Amnesty International alerted the authorities to the

harassment of Chinese-Canadian activists, the scale of which appeared “consistent with a coordinated, Chinese state-sponsored campaign.”

The dissident who seemed to be getting the worst of it: Sheng Xue.

“I think she’s a victim,” said

Andy Ellis, the former assistant director of operations for the Canadian Security Intelligence Service.

“I strongly do.

The Chinese government is trying to sully her reputation to advance their own interests.”

The Chinese Embassy in Ottawa declined to comment.

Rise to prominence. Flood of hate.

Sheng Xue, whose pen name is Mandarin for “abundant snow,” arrived in Canada in August 1989 on a visa to study journalism.

But while she had left China, she could not leave China behind.

Haunted by the sight of soldiers shooting into a crowd close to her family’s apartment during the

Tiananmen Square massacre in June of that year, Sheng Xue abandoned her study plans and threw herself into the burgeoning Chinese democracy movement in Toronto.

She helped form a local branch of the

Federation for a Democratic China, which at its height had 3,000 members in 25 countries.

Despite having forgone a degree, Sheng Xue broke into journalism and fashioned a successful career as a writer.

But she was best known for her activism — leading protests, lobbying governments and

helping fellow activists with their asylum cases.

In 2012, Canada’s immigration minister

gave her a medal for “extraordinary contributions to the country.”

A month later, she was elected president of the federation.

The first conference she hosted as the group’s president should have been a moment of glory. Hundreds came from across the globe.

Sheng Xue at a rally last year for political prisoners in front of the Chinese Consulate in Toronto.

Sheng Xue at a rally last year for political prisoners in front of the Chinese Consulate in Toronto.

The Chinese Consulate in Toronto.

The Chinese Consulate in Toronto.

Sheng Xue and her husband, Xin Dong, visiting the graveyard where her parents are buried in Mississauga, Ontario.

Sheng Xue and her husband, Xin Dong, visiting the graveyard where her parents are buried in Mississauga, Ontario.

The moment she remembers best, however, is stepping off the stage and finding herself surrounded by colleagues holding cellphones.

They were showing her emails they had just received, with various photos of her half-naked.

Except they were obvious fakes.

In one photo, Sheng Xue’s face was pasted onto another woman’s body.

Another email included a supposed love letter from her to an activist in Australia, so crass, it seemed a parody.

The sender appeared to be yet another activist,

Chin Jin, but he said the email was a fake.

There were sex-wanted ads posted in Sheng Xue’s name.

Lurid stories about her sex life.

Nude photos were published on a new Twitter account, of higher quality than the first ones, and harder to dismiss out of hand.

Some seemed to capture her kissing the Australian activist,

Xiaogang Zhang, although both say they are fakes.

The timing seemed beyond coincidence.

“There has been a pattern,” said

Jie Chen, an associate professor of international relations at the University of Western Australia who studies the Chinese democracy movement.

Pointing a finger at the Chinese Communist Party, he said,

“Whoever is doing well, whoever seems to be effective in damaging the reputation of the C.C.P., all of a sudden they will get attacked very systematically.”

‘I am the real Liu Shaofu’

The attacks appear to exploit tensions within the dissident movement, where Sheng Xue is a polarizing figure.

“People who love her, really love her,” said

Michael Stainton, the retired president of the Taiwanese Human Rights Association of Canada.

“People who despise her, really despise her.”

Many of her attackers are former friends and colleagues. But they say their identities were stolen.

Zhu Rui, a Chinese-Canadian author, began questioning Sheng Xue back in 2010, after the two traveled together to Dharamsala, India.

Since then, Ms. Zhu has penned many critical blog posts and assembled two e-books about Sheng Xue, accusing her of lying, personally profiting off refugee applicants and events, and being a fake witness to the Tiananmen Square massacre, among other things.

But in 2011, Ms. Zhu said, someone hacked into her computer, stole an unpublished essay about Sheng Xue and sent it to a dissident group posing as her.

Similarly,

Liu Shaofu, an elder of the democracy movement, said an impostor opened

a Twitter account with his name and photo to post criticism of Sheng Xue, including one fake nude photo.

Mr. Liu had collaborated with Sheng Xue for years, even living in her basement, but they had a public falling out in 2013.

“I am the real Liu Shaofu,” he wrote in his first tweet after setting up a

different account in June 2014.

“Don’t you feel ashamed you sent out so many tweets in my name?”

Sheng Xue at a hospital for a CT scan. She says that stress related to ongoing online attacks has compromised her health.

Sheng Xue at a hospital for a CT scan. She says that stress related to ongoing online attacks has compromised her health.

A portrait of Xi Jinping was defaced at a rally for political prisoners at the Chinese Consulate in Toronto.

A portrait of Xi Jinping was defaced at a rally for political prisoners at the Chinese Consulate in Toronto.

Toronto’s Chinatown district.

Toronto’s Chinatown district.

Perhaps Sheng Xue’s most vocal critic is

Fei Liangyong, a former federation president living in Germany who has accused her of a raft of moral failings, including “sexual impropriety and general wickedness.”

“To not criticize her would run counter to my democratic ideas and bring shame on my lifelong struggle for democracy and constitutional government in China,” he said in an email.

Mr. Fei’s essays have been widely republished on

anonymous anti-Sheng Xue blogs.

But he said he did not know who was behind them.

A

Twitter account with his name and photo, which Mr. Fei said he did not create, posted links to one of the blogs.

Many fellow activists, even those who have themselves been targeted by the Chinese government, believe some of the accusations against Sheng Xue.

“The Chinese government tries all means to marginalize, to silence and detain Chinese activists, in China and outside,” said

Teng Biao, a civil rights lawyer who escaped China in 2012 and now lives in New Jersey.

But, he added, “what happened to Sheng Xue might be a little complicated, because as far as I know, some claims are true.”

Taken together, a pattern emerges: Doubt is turned into distrust, and dislike into loathing.

“It’s called blowing on the hot coals,” said Mr. Bequelin of Amnesty International.

A movement splintered

Sheng Xue learned the Chinese government had her on its black list in 1996, when she tried to return to Beijing.

She was stopped at the airport, interrogated and sent back to Canada the next day.

Since then, it has become clear she remains a target, and at least three comrades in Canada report pressure from Chinese security services over their ties to her.

One,

Yi Jun, said every time he returned to China, he was taken to tea by members of the Communist security bureau.

“They say Sheng Xue is very counterrevolutionary and a very bad person,” said Mr. Yi, the president of the federation’s Toronto branch.

Another dissident,

Leon Liang, said his wife back in Shenzhen was visited regularly by the authorities and given a warning: “If I didn’t inform on Sheng Xue, they would take her job.”

The attacks on Sheng Xue have taken a toll not just on her but on the dissident movement itself.

The federation, which had already dwindled to about 100 members, split in two in 2017, with Mr. Fei forming a second group.

Sheng Xue has stepped down as president.

The fight was so public and ugly, it tarnished everyone.

One member in Germany distributed an “investigation” a year after the death of Sheng Xue’s mother,

claiming that she had pimped out her young daughters, and that it was the source of Sheng Xue’s moral bankruptcy.

“I really lament the fact the organization founded by Tiananmen Square leaders and intellectuals has degenerated to such a miserable state,” said Mr. Chen, the University of Western Australia professor.

Few dissidents will fail to get the message, said

Michel Juneau-Katsuya, a former Canadian intelligence officer specializing in China: “If you participate and support these people, look what I can do to you. Your local government won’t be able to protect you.”

Sheng Xue lives in a bungalow in a suburb of Toronto. Many fellow dissidents stay there, renting rooms in the basement.

Sheng Xue lives in a bungalow in a suburb of Toronto. Many fellow dissidents stay there, renting rooms in the basement.

The walls of Sheng Xue’s living room are decorated with photos of her with influential people, including the Dalai Lama and Richard Gere.

The walls of Sheng Xue’s living room are decorated with photos of her with influential people, including the Dalai Lama and Richard Gere.

Sheng Xue with friends and supporters during her birthday party.

Sheng Xue with friends and supporters during her birthday party.

Sheng Xue continues her activism, but her health has been declining.

She has met with doctors about heart palpitations and headaches.

She never found an effective defense against the campaign, which she dismisses in totality as lies.

Some of her supporters formed a “Friends of Sheng Xue” organization,

declaring the attacks a “threat to Canada’s sovereignty and security.”

They got nowhere.

In its report, Amnesty International urged the Canadian government to fashion a “comprehensive approach to addressing this problem,” and suggested a complaint hotline.

That has not happened.

In 2016, a Chinese-Canadian human rights lawyer,

Guo Guoting, volunteered himself as an arbiter between Sheng Xue and Mr. Fei.

He considers both friends.

Mr. Guo moved into Sheng Xue’s home for a month and began researching the attacks.

But his computer was hacked, he said, and “all the documents disappeared.”

He never published his report.

Senator Josh Hawley (R., Mo.)

Senator Josh Hawley (R., Mo.)