Google Is Handing the Future of the Internet to China

The company has been quietly collaborating with the Chinese government on a new, censored search engine—and abandoning its own ideals in the process.BY SUZANNE NOSSEL

In May,

Google quietly removed “Don’t be evil” from the text of its corporate code of conduct, deleting a catchphrase that had been associated with the company since 2000.

Amid startling revelations of how social media and internet platforms can enable political interference and new forms of stealthy cyberwarfare, avoiding evil in Silicon Valley has turned out to be harder than it looks.

In a world where Twitter’s terrorist may be Facebook’s freedom fighter, decisions over what content to algorithmically uplift or suppress can involve agonizing questions of interpretation, intent, and cultural context.

But amid all the moral ambiguity and uncharted terrain of running an internet platform that controls vast swaths of global discourse and reaps commensurate revenues, some dilemmas are more straightforward than others.

That’s why word of Google’s plans to substantially expand its currently minimal role in the Chinese market—through the potential launch of a censored search engine code-named

Dragonfly—has provoked such uproar.

The plans were revealed through documents leaked to the

Intercept, which

reported that prototypes and negotiations with the Chinese government were far along, laying the groundwork for

the service to launch as soon as early 2019.

In late August, a group of free expression and human rights organizations published a

joint letter proclaiming that the launch of a Chinese search application would represent

“an alarming capitulation by Google on human rights.”

Six U.S. senators, led by

Marco Rubio and

Mark Warner, sent a

letter to Google CEO

Sundar Pichai demanding answers to a series of queries about the company’s intentions.

Last week, PEN America sent a

detailed letter to Google executives spelling out specific human rights issues and subjects that, per Chinese censorship rules, would be treated repressively and deceptively by any information platform operating in the country.

Google’s own employees are also up in arms: More than 1,400 signed a letter to management saying the floated China project “raise[s] urgent moral and ethical issues” and demanding greater transparency before any plans are implemented.

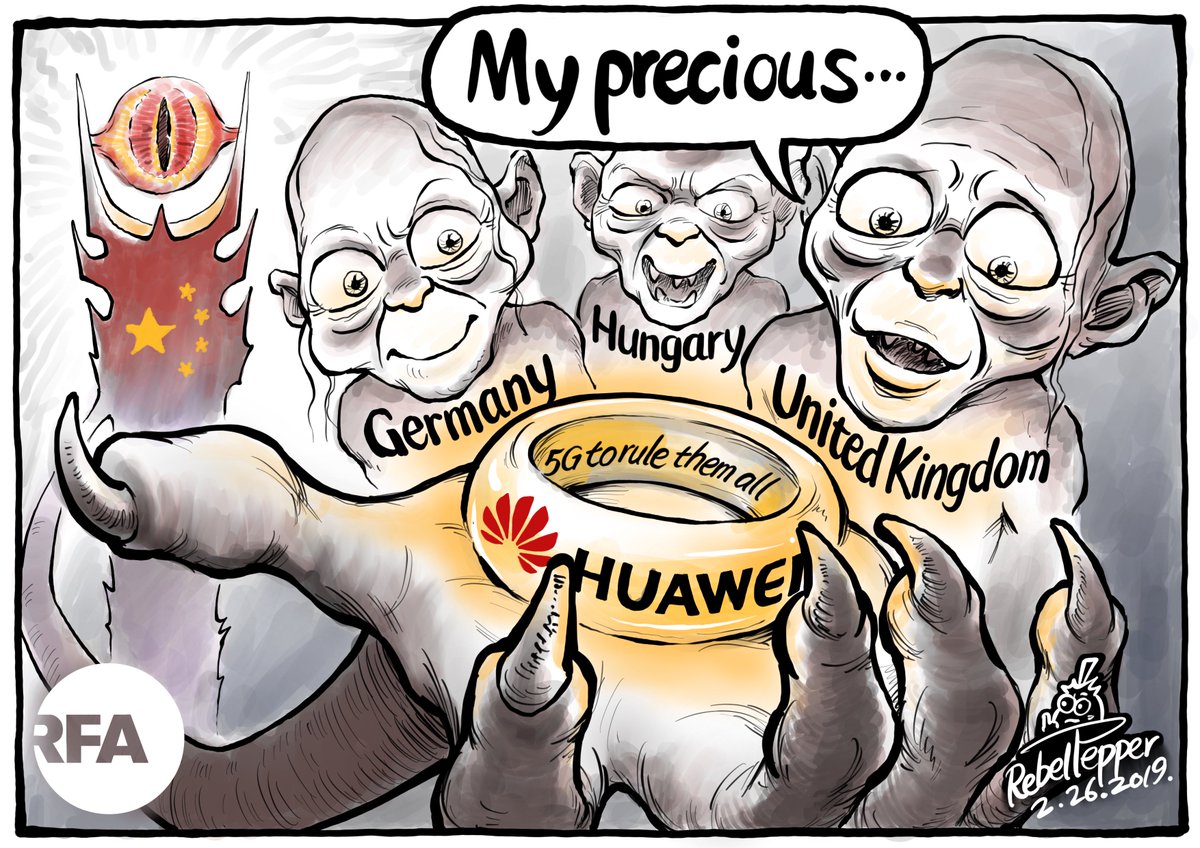

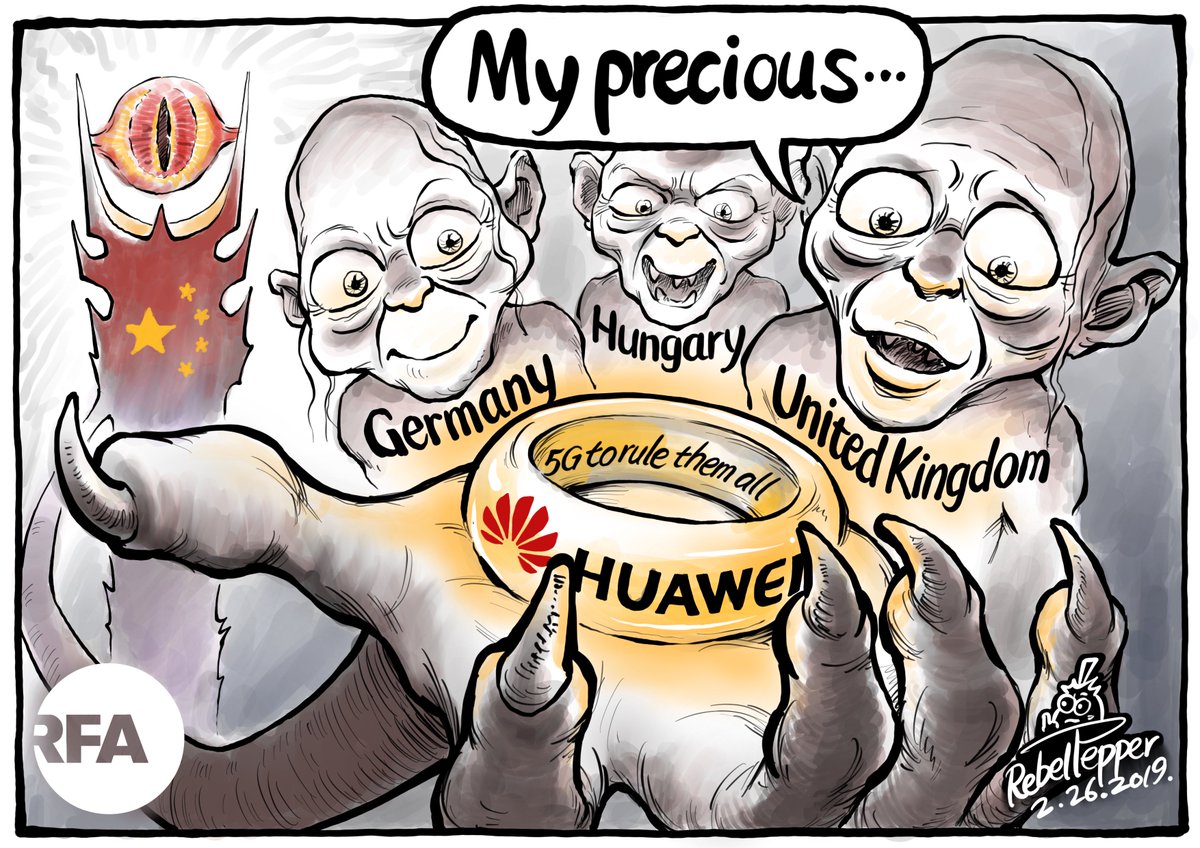

In demonstrating that a company as mighty as Google was unable to resist the allure of the Chinese market, despite the terms of entry, Beijing will advance its campaign to remake global internet governance on its own terms.

The utopian notion of an internet that unifies people across borders, fosters the unfettered flow of information, and allows truth and reason to triumph is already under attack on multiple fronts.

The trade-off, to date, has been that countries insistent on controlling the internet have had to forfeit access to the world’s most powerful and innovative online services in favor of local providers.

If Google is willing to play along with China, governments in Russia, Turkey, Iran, Egypt, and elsewhere will have little reason not to fortify their own measures to control content and opinion.

At a time when even the U.S. president is attacking Google and other platforms as biased and rigged, for the company to signal a new willingness to bow before an overreaching government would represent a grave setback for the rights of citizens to harness digital technology as a tool of empowerment.

Google is no stranger to the Chinese market or to the moral dilemmas it poses.

Google first began offering a Chinese-language version of its search engine back in 2000.

Periodic blocking and slowdowns caused by filtering through China’s Great Firewall made the service clunky and unreliable on the mainland.

In 2006, Google launched a Google.cn service based in China, agreeing to block certain websites in return for being licensed to operate in the country.

The company promised to tell mainland users when results were being withheld and to avoid offering services that would require housing confidential user data on Chinese servers.

At the same time, native Chinese internet services such as Baidu and Tencent began to gain steam. Chinese authorities were brazen in utilizing Western online services to surveil and track down dissenters.

In a

notorious 2007 incident, it was revealed that

Yahoo had turned over private information about two journalists at the request of Chinese authorities, resulting in 10-year prison sentences for the men and a global uproar at the spectacle of a U.S. company betraying its users to an authoritarian regime. The company settled a lawsuit with the families of the two men, established a $17 million fund to support Chinese dissidents, and faced a congressional investigation in which Rep.

Tom Lantos infamously

chided, “While technologically and financially you are giants, morally you are pygmies.”

It’s not just Yahoo.

In 2008, the Chinese human rights scholar and activist Guo Quan threatened to sue Yahoo and Google for omitting his name from search results inside China.

He wrote in an

open letter:

“To make money, Google has become a servile Pekinese dog wagging its tail at the heels of the Chinese Communists.”

He has been serving a 10-year prison sentence since 2009.

That same year, the Chinese government punished Google, purportedly for failing to adequately screen out pornography, by limiting its reach and advantaging its leading local search competitor, Baidu.

In January 2010, Google issued a detailed

statement declaring that it would stop censoring Chinese search results and was prepared to pull out of the market.

It announced that the service had been targeted by attacks aimed at hacking the Gmail accounts of Chinese human rights defenders and their supporters around the world.

The corporate release reflected on Google’s aspirations and trajectory in China, saying it had entered the country “in the belief that the benefits of increased access to information for people in China and a more open Internet outweighed our discomfort in agreeing to censor some results.”

The statement went on to say that four years later, in the face of continued attacks and surveillance, “combined with the attempts over the past year to further limit free speech on the web … we are no longer willing to continue censoring our results on Google.cn. … We recognize that this may well mean having to shut down Google.cn, and potentially our offices in China.”

After failed attempts to negotiate a way to remain in China by redirecting local traffic to Google’s Hong Kong site, the company effectively pulled out of the market later that year, maintaining only a token presence and small staff.

It is not hard to understand why Google’s corporate bosses have grown wistful about the Chinese market.

According to a September 2017

report by the Boston Consulting Group, with more than 700 million users (nearly as many as the next two biggest markets—India and the United States—combined) and close to $100 billion in revenue, China has become the world’s largest internet market by several measures, behind only the United States in terms of online spending.

The future upside seems nearly boundless.

With its vast and upwardly mobile rural population, growth rates in Chinese internet use far outpace any other market, with internet penetration rates still lagging well behind those of other G-20 countries.

Right behind the U.S. tech giants Google, Amazon, and Facebook, five of the world’s 10 largest internet companies are Chinese, including Tencent, Alibaba, and Baidu.

China is also home to 29 to 40 percent of the world’s “unicorns,” defined as privately held start-ups valued at more than $1 billion.

For a leading global player to be shut out of an increasingly critical and dynamic market could pose long-term risks for Google’s business.

Given those metrics, it is no surprise that Google’s management has continued to explore ways to re-enter the country.

For a long time, Western CEOs and politicians expounded the view that deepening commercial and cultural ties between China and the rest of the world would inevitably crack open Beijing’s tight stranglehold on political freedom and freedom of speech.

This theory conveniently dictated that even if, in the near term, companies such as Google were forced to jettison corporate values in order to take part in the market, that sacrifice could be justified over time since their very presence in China would steadily foster a loosening of constraints.

In 2005, then-British Prime Minister Tony Blair gushed at the end of a visit to China that “in a country that is developing very fast, where 100 million people now use the internet, and which is going to be the second-largest economy in the world … there is an unstoppable momentum toward greater political freedom.”

Blair was dead wrong.

Whatever fleeting momentum might once have existed ground to a halt in 2013 with the ascent of

Xi Jinping, who ushered in a period of

tightening, consolidating repression of free expression, press freedom, political dissent, protest rights, and other civil liberties.

The premise of short-term trade-offs by Western companies in order to contribute to an inevitable long-range trend toward liberalization might been plausible when Google and others first entered China in the early 2000s.

But it isn’t now.

As documented in a

March report by PEN America, titled “Forbidden Feeds: Government Controls on Social Media in China,”

the mushrooming Chinese internet sector has walled itself off from outside influence.

Beijing has created a set of rules and operating paradigms that are deeply entrenched, robustly enforced, almost universally adhered to, and scarcely challenged.

The Chinese are constantly implementing new technological methods of surveillance and tracking, as well as enacting new laws that zip shut channels of dissent and methods of circumvention.

The PEN America report states: “Those who dare to test the limits of China’s online censorship can face intimidation, job loss, years-long prison sentences, or find themselves forced into exile. … [T]he vague and broad nature of China’s censorship rules means that the ‘red lines’ of posting or conversing on social media are continually drawn and re-drawn, and socially-engaged authors and bloggers who wish to make their voices heard online are faced with difficult choices: take one’s chances in speaking freely, self-censor, withdraw from the conversation, or leave the country.”

For media companies, there is no wiggling free from government dictates.

“China’s legal system conscripts domestic social media companies to be active participants in the monitoring and censorship of their own users. Chinese companies have no choice but to operate in accordance with the government’s demands. … Within the existing censorship framework, there is simply no way for foreign social media companies to operate in China without becoming active partners in the government’s efforts to silence dissent through censorship, mass surveillance, and the use of criminal charges,” the report adds.

China’s approach is underpinned by a sweeping philosophical conception of the internet, premised on the notion of cybersovereignty, a vision that “rejects the universalism of the internet in favor of the idea that each country has the right to shape and control the internet within its own borders.”

China is working actively to export this concept for adoption by other authoritarian countries and in

United Nations forums.

This paradigm stands in direct opposition to the conception of an open internet that digital rights activists, human rights organizations, tech leaders, and even

the United Nations have long espoused. Yet

Western CEOs hungry to enter the Chinese market have begun to moderate their public statements, tacitly eliding the essential distinctions between an internet that is open and one that is government-controlled.

***

Against this backdrop, the leaked plans for Google’s aspiring re-entry into China are troubling.

The Intercept reported that all websites blocked in China—including the BBC and Wikipedia—will be unavailable via Google search, replaced by an anodyne disclaimer revealing only that “some results may have been removed due to statutory requirements.”

So-called “sensitive queries” will be placed on a “blacklist,” meaning that people, topics, and photographs banned by the government will be expunged from any appearance via Google.

Lest anyone argue that, given the dominance of local players, Google’s role in the market may not be significant, the leaked documents make clear that the company is setting out to go head to head with China’s dominant search engine, Baidu.

While Microsoft’s Bing search engine has operated in China for years without attracting significant criticism, it accounts for a smaller share of the Chinese market—

just 1.27 percent—than does Google itself, eight years after effectively closing up shop on the mainland.

Google is not a bit player anywhere, and doesn’t intend to be one in China.

The ethical dilemmas raised by Google’s plans are sweeping.

For Chinese individuals who somehow cross the government, the prospect of being erased from existence on Google is a new and dehumanizing digital version of being declared stateless, persona non grata, or otherwise unworthy of the right to simply exist in the country in which you live.

For ordinary users who take advantage of Google’s services, the government’s right to access personal data—such as search histories—housed on corporate servers would be absolute.

An

appendix to the PEN America report documents the

cases of 80 Chinese citizens who have been targeted, detained, or prosecuted for online postings.

The list includes people such as the writer Wu Yangwei, who was detained and strip-searched after broadcasting a press freedom protest online; the women’s rights activist Su Changlan, who was convicted of “subversion” for posting articles and comments supportive of Hong Kong’s Umbrella protests; and the blogger Duan Xiaowen, who has been imprisoned and tortured for blogging about government corruption.

Another prominent example of an online dissident was 2010 Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo, who died of liver cancer last year while serving an 11-year prison sentence in part for his role in drafting the online “Charter 08” petition on freedom and democracy.

The prospect of Google helping to build cases against such courageous advocates is dire.

While disclaimers and usage agreements may technically put Google users on alert that their searches (and, potentially, emails, texts, and documents depending on the scope of services Google ultimately offers) are all within easy reach of the government, Google’s business model relies on free-flowing exploration and discovery that run counter to the extreme caution that would be required to avoid triggering official scrutiny.

When users are arrested and prosecuted for promulgating dissenting ideas in personal communications on Google, the company may play a role as a mandated purveyor of essential evidence to enable conviction.

Google’s compliance with Chinese censorship directives will also have an unavoidable, distorting impact on online discourse in the world’s most populous country, obscuring the truth, reifying government-sanctioned orthodoxies, denying history, and furthering the repression of persecuted groups.

Chinese government organs are estimated to issue thousands of separate censorship directives annually, charging all companies with compliance under threat of severe sanction or shutdown. Discussion of the Tiananmen Square protests, Taiwan’s independence, and the rights of Tibetans is forbidden, and those who violate the strictures face harsh punishment.

Beyond those three top taboo topics, Google may be required to deny its users vital information about health and safety threats when such information casts a negative light on the state, including vaccinations, pollution, and disease controls.

Those who use Google to search for information on human rights violations—including the pervasive, forced detainment of hundreds of thousands of ethnic minority residents of China’s East Turkestan colony—will find only whitewashed accounts that provide cover for the government’s abusive campaigns.

Articles or posts questioning China’s frequent use of forced confessions will be banned, helping to shield this brutal practice from scrutiny.

Other topics certain to be off-limits include the rights of other ethnic minorities; the mistreatment and premature deaths of Chinese political prisoners; politically motivated charges and show trials of activists, human rights lawyers, and independent scholars; and extrajudicial renderings of Chinese and foreign citizens throughout Asia.

Whereas Google has positioned itself as a

champion of the #MeToo movement, it will be

required to censor that and related hashtags in China, denying survivors of sexual assault and abuse a desperately needed voice.

Google executives make the point that all digital platforms must adhere to local law in the countries in which they operate, and that doing so often includes imposing some forms of censorship.

In Germany, Holocaust denial and other forms of hateful speech are prohibited, for example, with strict penalties for platforms that neglect to remove offending content.

Internet platforms are profit-making entities, not human rights organizations.

Like all businesses, they weigh competing considerations and confront circumstances in which professed corporate values bump up against business considerations.

But after making a principled, high-profile retreat from China years ago to protest the country’s intrusive and coercive policies, Google’s choice to re-enter now will deal a huge victory to Beijing and its campaign to entrench cybersovereignty in the global order.

As it is, for Chinese internet users imbibing music, celebrity content, recipes, or videos, the fact that the system keeps certain content strictly off-limits is easy to forget—or scarcely noticed in the first place.

Hundreds of millions of Chinese internet users are inured to a universe where dissent, conflict, and uncomfortable facts don’t exist.

At least, as of today, they recognize that the systems they utilize are Chinese and are aware that beyond their borders other versions of the internet exist.

With Google becoming newly available in China under the same terms as existing local services, even the notion that a wider, more open internet may be out there somewhere will fade.

***

The signal sent by the world’s largest internet company acquiescing to Chinese dictates it once eschewed will ratify and legitimize Beijing’s repressive rules.

Moreover, even if Google officials were somehow to get comfortable with the strictures imposed as the conditions of the company’s initial re-entry into China, the terms of its presence will be forever subject to Chinese government whim.

Google described its decision to leave China eight years ago as “

incredibly hard.”

With the market having mushroomed since, and having weathered the furor accompanying its possible re-emergence, a second such retreat would be even more painful.

Those disincentives for exit will afford the Chinese government near boundless leverage: What if it chooses to censor all critical coverage of Chinese policies or those of its allies?

Or to ban all favorable descriptions of the United States?

Having crossed what it once described as “red lines,” it may be impossible for Google to set any new ones.

Moreover, once it has re-established its leverage over Google, Beijing is unlikely to confine its demands within its borders.

This year, China

demanded that global airlines begin to list Taiwan as part of China, not just within the mainland, but on all websites, fare listings, and promotions globally.

Almost all carriers complied immediately.

With the growth of China’s film market, Hollywood studios now factor in Chinese censors in the production of action movies in order to ensure that the final cuts—slated for global release—pass muster with the country’s minders.

The result is that major blockbusters are written and filmed to avoid irking Beijing.

The growing influence of Chinese government-funded

Confucius Institutes at U.S. universities has resulted in a shadowy hand of censorship being felt at

academic conferences and

on campuses.

Once Google’s new Chinese business is up and running, there will be nothing to stop Beijing from seeking to dictate how references to Taiwan are addressed not just in China but throughout the site globally.

China will demand to shape how protests in Taiwan, Hong Kong, or the mainland are addressed or what happens when people search for dissidents such as Liu Xiaobo or topics such as human rights.

While Google executives may believe that their company would never accede to such requests outside of China’s borders, there are no guarantees.

If China gains the leverage to shape how Google presents what Beijing considers to be sensitive topics throughout the rest of the world, it will deal a mortal blow to international principles of freedom of expression and thought.

When facing dubious employees at an internal meeting in mid-August, Google’s Pichai maintained that the company’s plans for China were far from finalized, insisting that many options remained on the table.

Google is not wrong to keep its eye on China and weigh every angle in analyzing whether the company can enter the market without doing more harm than good.

But the company’s vast size, visibility, and influence make it impossible to downplay the ill consequences that would result if it turned its back not only on independent thinkers in China but also on the value system that has underpinned an open internet and the rise of Google itself.

The efficacy of China’s authoritarianism may cause some to privately wonder whether resistance to Beijing’s repression is futile.

It is tempting to put aside thoughts of beleaguered, isolated Chinese dissidents in the drive to serve millions of ambitious, striving young Chinese, who have every incentive to avoid touching political third rails.

In his speech to Google staff last month, Pichai said: “Stepping back, I genuinely do believe we have a positive impact when we engage around the world, and I don’t see any reason why that would be different in China.”

But in the rest of the world, Google has brought people newly potent tools for search and information discovery.

In China, such tools already exist, operating within stringent government constraint.

All Google can offer to China that is truly new would be the imprimatur of one of the world’s most powerful brands on an unparalleled system of internet censorship and control—a system that is tightening, expanding, and presenting a formidable counterweight to the values and principles that allowed Google to rise and thrive in the first place.

Senate Intelligence Committee Vice Chairman Mark Warner, D-Va., shake hands with FBI Director Christopher Wray as CIA Director Gina Haspel looks on before the Senate Intelligence Committee hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington, Jan. 29, 2019.

Senate Intelligence Committee Vice Chairman Mark Warner, D-Va., shake hands with FBI Director Christopher Wray as CIA Director Gina Haspel looks on before the Senate Intelligence Committee hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington, Jan. 29, 2019. Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats testifies to the Senate Intelligence Committee hearing about worldwide threats on Capitol Hill in Washington, U.S., Jan. 29, 2019.

Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats testifies to the Senate Intelligence Committee hearing about worldwide threats on Capitol Hill in Washington, U.S., Jan. 29, 2019. Senator Marco Rubio questions witnesses before the Senate Intelligence Committee hearing about "worldwide threats" on Capitol Hill in Washington, Jan. 29, 2019.

Senator Marco Rubio questions witnesses before the Senate Intelligence Committee hearing about "worldwide threats" on Capitol Hill in Washington, Jan. 29, 2019. Senate Intelligence Committee Vice Chairman Mark Warner, D-Va., speaks during the Senate Intelligence Committee hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington, Jan. 29, 2019.

Senate Intelligence Committee Vice Chairman Mark Warner, D-Va., speaks during the Senate Intelligence Committee hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington, Jan. 29, 2019.

Facebook’s logo at an internet conference in Beijing in April. The social network has struck data-sharing partnerships with at least four companies in China.

Facebook’s logo at an internet conference in Beijing in April. The social network has struck data-sharing partnerships with at least four companies in China.