By EMILY FENG

Chinese-style tile has replaced the domes and domed minarets of the Hongsibao Mosque in China's Ningxia region. Ningxia is home to a large concentration of Hui Muslims, who have long prided themselves on assimilation but are under increasing scrutiny by Chinese authorities.

Gold-domed mosques and gleaming minarets once broke the monotony of the Ningxia region's vast scrubland every few miles.

This countryside here is home to some of China's 10.5 million Hui Muslims, who have practiced Sunni or Sufi forms of Islam within tight-knit communities for centuries, mainly in the northwest and central plains.

Concentrated in the Ningxia region, the Hui are China's third-largest ethnic minority.

Now, though, virtually every mosque in Ningxia's countryside has been denuded of its domes, part of a sweeping crackdown on China's Muslim minorities that has reached Hui strongholds in Ningxia, in central China, and as far inland as Henan province in the east. (Up to now, Gansu province in central China has been able to keep most of its mosques intact.)

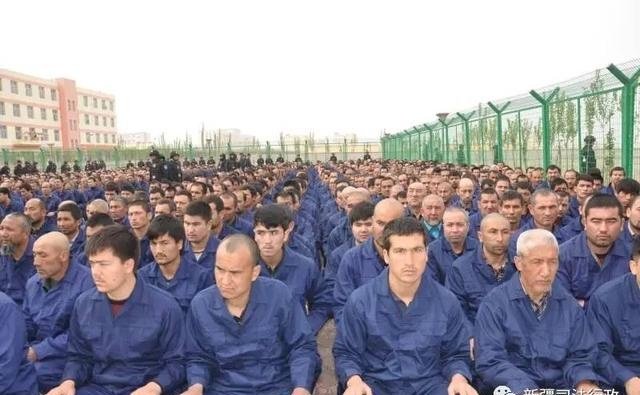

The crackdown on Muslims has been most extreme in the northwestern colony of East Turkestan, where scholars estimate that up to 1.5 million Muslim Uighurs, a Turkic-speaking group, and other ethnic minorities have been detained since 2016, in one of the most sophisticated surveillance states in the world.

The same restrictions that preceded the East Turkestan crackdown on Uighur Muslims are now appearing in Hui-dominated regions.

Now, though, virtually every mosque in Ningxia's countryside has been denuded of its domes, part of a sweeping crackdown on China's Muslim minorities that has reached Hui strongholds in Ningxia, in central China, and as far inland as Henan province in the east. (Up to now, Gansu province in central China has been able to keep most of its mosques intact.)

The crackdown on Muslims has been most extreme in the northwestern colony of East Turkestan, where scholars estimate that up to 1.5 million Muslim Uighurs, a Turkic-speaking group, and other ethnic minorities have been detained since 2016, in one of the most sophisticated surveillance states in the world.

The same restrictions that preceded the East Turkestan crackdown on Uighur Muslims are now appearing in Hui-dominated regions.

NPR has learned that since April 2018, Hui mosques have been forcibly renovated or shuttered, schools demolished and religious community leaders imprisoned.

Hui who have traveled internationally are increasingly detained or sent to reeducation facilities in East Turkestan.

In August 2018, in Ningxia's Tongxin county, authorities attempted to demolish the Weizhou Grand Mosque, claiming it lacked the right building permits.

In August 2018, in Ningxia's Tongxin county, authorities attempted to demolish the Weizhou Grand Mosque, claiming it lacked the right building permits.

Hundreds of furious residents staged a sit-in, sharing videos of their protest through popular Chinese social media platforms like WeChat and Kuaishou, a live-streaming app, faster than censors could take them down.

Taken aback, officials called off the demolition.

Taken aback, officials called off the demolition.

But the victory was short-lived.

In November, local government work units began visiting every household in Weizhou, pressuring residents to sign letters stating their acquiescence to "renovate" the mosque by removing its main dome and domed minarets.

In some cases, Weizhou officials threatened to fire state employees if they did not sign the letter, according to multiple residents.

This month, NPR drove through Weizhou, which is now guarded by checkpoints on the only road leading in and out of town.

This month, NPR drove through Weizhou, which is now guarded by checkpoints on the only road leading in and out of town.

The mosque is closed, its main dome and minarets replaced with tiled Buddhist-style pagodas, and its entrances blocked by scaffolding.

The domes and minarets of the Weizhou Grand Mosque in Ningxia have been replaced with tiled pagodas, NPR found in a visit this month to Weizhou.

The domes and minarets of the Weizhou Grand Mosque in Ningxia have been replaced with tiled pagodas, NPR found in a visit this month to Weizhou.

"Of course we are afraid we will become the next East Turkestan," one Hui man told NPR.

He did not provide his name for fear that authorities in East Turkestan would find him.

Three years ago, he abandoned his family's property in East Turkestan in order to transfer his residency to Tongxin county.

"But what can an individual do? We can only take it year by year."

"We say what we have to say"

Descendants of Arab traders who entered China some 1,500 years ago, the Hui pride themselves on having thoroughly assimilated into Chinese society.

"We say what we have to say"

Descendants of Arab traders who entered China some 1,500 years ago, the Hui pride themselves on having thoroughly assimilated into Chinese society.

Unlike the Uighurs, the Hui have no distinct language, speaking Mandarin and often some Arabic. Save for the occasional white cap customarily worn by Hui men or hair coverings among women, they are often visually indistinguishable from China's ethnic majority, the Han.

Their exemption from the harshest of religious restrictions changed in April 2018, when the Chinese Communist Party's United Front Work Department formally took control of the State Bureau of Religious Affairs — meaning that the party now directly oversees policy for religious affairs, not the government.

"The day-to-day responsibility for managing religious activities and organizations shifted to the UFWD, and its atheist party apparatchiks, whose overarching mission is the protection of party power," James Leibold, an associate professor at Australia's La Trobe University and an expert on China's ethnic minority policy, tells NPR via email.

That same April, a mass dome-removal campaign began in Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan province in central China, and resumed in Ningxia as part of the official effort known as chu shahua, fan ah'hua, to "combat Saudi and Arabic influence."

All Hui-run nursery schools, child care centers and religious schools were forcibly closed in Ningxia and across Yunnan and Henan provinces, which are also home to a large number of Hui Muslims.

Plans for "renovation" of the Gongmazhuang mosque outside Zhengzhou city in Henan province include removing its domes.

Their exemption from the harshest of religious restrictions changed in April 2018, when the Chinese Communist Party's United Front Work Department formally took control of the State Bureau of Religious Affairs — meaning that the party now directly oversees policy for religious affairs, not the government.

"The day-to-day responsibility for managing religious activities and organizations shifted to the UFWD, and its atheist party apparatchiks, whose overarching mission is the protection of party power," James Leibold, an associate professor at Australia's La Trobe University and an expert on China's ethnic minority policy, tells NPR via email.

That same April, a mass dome-removal campaign began in Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan province in central China, and resumed in Ningxia as part of the official effort known as chu shahua, fan ah'hua, to "combat Saudi and Arabic influence."

All Hui-run nursery schools, child care centers and religious schools were forcibly closed in Ningxia and across Yunnan and Henan provinces, which are also home to a large number of Hui Muslims.

Plans for "renovation" of the Gongmazhuang mosque outside Zhengzhou city in Henan province include removing its domes.

The United Front's new control over Chinese ethnic and religious policy marks a substantial change, says Leibold.

While the State Bureau of Religious Affairs was sometimes restrictive, it at least "saw the protection, if not promotion, of 'normal religious activities' as part of their mission and mandate, and many of its officials were religious practitioners themselves," he says in his email to NPR.

Abroad, the United Front is the party body that liaises with international nonstate individuals and organizations.

Abroad, the United Front is the party body that liaises with international nonstate individuals and organizations.

Domestically, the United Front has emerged as one of the most aggressive proponents of stripping away foreign influences within religious practices and bringing them under state control — making them more Chinese, a process known as "Sinification."

"Sinification of religion in China is an important discourse of Party General Secretary Xi Jinping on the problem of religion and religious work," Ma Jin, a United Front official, told the Islamic Association of China, a state-backed organization, in January.

"Sinification of religion in China is an important discourse of Party General Secretary Xi Jinping on the problem of religion and religious work," Ma Jin, a United Front official, told the Islamic Association of China, a state-backed organization, in January.

"This recent crackdown on the Muslim activities is really a part of a national campaign of China today to correct what they believe are the excesses in permitting Arab-style mosques ... and influence by the Middle East. The Salafi and Wahhabi groups have been pouring money in China," says Dru Gladney, an anthropologist at Pomona College and an expert on Hui Muslims.

"These restrictions through UFWD are part and parcel of government efforts to control Islamic practices, to make them more Chinese."

In East Turkestan, Uighur-language books and films have been expunged, Uighur intellectuals imprisoned, and Uighur children sent to state-run schools to be taught Mandarin Chinese and culture.

For the Hui across China, mosques have become the major vehicle for Sinification.

In East Turkestan, Uighur-language books and films have been expunged, Uighur intellectuals imprisoned, and Uighur children sent to state-run schools to be taught Mandarin Chinese and culture.

For the Hui across China, mosques have become the major vehicle for Sinification.

In April 2018, authorities began revoking the state-issued licenses given to imams who have residency outside the province in which they practice and from those who have studied abroad.

In Ningxia, smaller mosques without licensed imams have been closed outright.

Ningxia sent senior leadership delegations to visit East Turkestan's detention camps last November and signed a counterterrorism cooperation agreement with East Turkestan a month later.

Like many mosques, the Huarenjie mosque in downtown Zhengzhou, Henan, is now monitored around the clock through a network of surveillance cameras installed last year by the local public security bureau.

Ningxia sent senior leadership delegations to visit East Turkestan's detention camps last November and signed a counterterrorism cooperation agreement with East Turkestan a month later.

Like many mosques, the Huarenjie mosque in downtown Zhengzhou, Henan, is now monitored around the clock through a network of surveillance cameras installed last year by the local public security bureau.

Imams in Henan and Ningxia must now attend monthly training sessions that can last for days.

There, imams told NPR, they are taught Communist ideology and state ethnic policy and discuss Xi Jinping's speeches.

Imams must then pass an exam testing their ideological knowledge in order to renew their license each year, mirroring how the government issues licenses to imams in the East Turkestan colony.

"We go along with it. We say what we have to say, because it is just words, and it lets us continue to work in the mosque," said one of the few imams still based in Henan, requesting his name be kept anonymous because of fears of political reprisal.

Fears of Saudi influence

Mosque employees say orders to demolish mosque domes and minarets are transmitted orally from local officials citing the United Front, with no written notice.

"We go along with it. We say what we have to say, because it is just words, and it lets us continue to work in the mosque," said one of the few imams still based in Henan, requesting his name be kept anonymous because of fears of political reprisal.

Fears of Saudi influence

Mosque employees say orders to demolish mosque domes and minarets are transmitted orally from local officials citing the United Front, with no written notice.

The demolitions are swiftly executed at night, to avoid protests and video documentation.

"We ourselves do not even have the documents. [The United Front] takes them back at the end of each meeting," a local Henan official says in a recording NPR listened to of a meeting between local officials and employees at a mosque whose domes were removed after the meeting.

"Party organs like the UFWD work outside the state legal system and thus have far greater power than the state bureaucracy and are not required to report back to the State Council," the equivalent of China's cabinet, says Leibold.

Others say officials are looking to avoid the attention that mass mosque demolitions and detentions of Muslims in East Turkestan have attracted.

"Local officials learned from East Turkestan. They know that by aggressively restricting people in obvious ways, like constructing detention centers and leaving written evidence, they might create resistance," Tianfang, the pen name of a prominent blogger critical of China's religious policies, told NPR.

The crackdown on China's Hui Muslims is in part driven by the government's fears that fundamentalist strains of Islam like Salafism and Wahhabism are filtering into China by way of Hui students who study in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan and through private religious foundations on the Arabian Peninsula that have funded some Hui social enterprises and mosques.

Signs of Saudi influence, including Arabic script, are being removed across China.

"We ourselves do not even have the documents. [The United Front] takes them back at the end of each meeting," a local Henan official says in a recording NPR listened to of a meeting between local officials and employees at a mosque whose domes were removed after the meeting.

"Party organs like the UFWD work outside the state legal system and thus have far greater power than the state bureaucracy and are not required to report back to the State Council," the equivalent of China's cabinet, says Leibold.

Others say officials are looking to avoid the attention that mass mosque demolitions and detentions of Muslims in East Turkestan have attracted.

"Local officials learned from East Turkestan. They know that by aggressively restricting people in obvious ways, like constructing detention centers and leaving written evidence, they might create resistance," Tianfang, the pen name of a prominent blogger critical of China's religious policies, told NPR.

The crackdown on China's Hui Muslims is in part driven by the government's fears that fundamentalist strains of Islam like Salafism and Wahhabism are filtering into China by way of Hui students who study in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan and through private religious foundations on the Arabian Peninsula that have funded some Hui social enterprises and mosques.

Signs of Saudi influence, including Arabic script, are being removed across China.

Hui women in Henan and Ningxia provinces say they are no longer allowed to wear the head-to-toe black abaya customary to Saudi women, and Hui shops say they no longer stock Saudi-style clothes for men or women.

Imams suspected of preaching Salafism are also promptly removed.

Imams suspected of preaching Salafism are also promptly removed.

One of them, Han Daoliang, was the imam at Huarenjie Mosque in Zhengzhou, Henan province's capital, according to mosque attendees.

Han raised his hands three times during prayer instead of just once, they said, marking him to Zhengzhou officials as a Salafi adherent.

Hui tombstones inscribed in Arabic outside Xiaomagou Mosque in Zhengzhou, Henan.

Hui tombstones inscribed in Arabic outside Xiaomagou Mosque in Zhengzhou, Henan.

Forced by local officials to resign this year, Han is now living in Malaysia, according to acquaintances.

His former mosque has been given a state-appointed imam.

According to a new plaque and mosque employees, the house of worship is now run by a new committee appointed by the state, with a board including two non-Muslim government officials.

"Sweep away the black and root out evil"

The crackdown on Hui Muslims is backed by a national anti-corruption effort launched by the government in 2018 to "sweep away the black and root out evil."

"Sweep away the black and root out evil"

The crackdown on Hui Muslims is backed by a national anti-corruption effort launched by the government in 2018 to "sweep away the black and root out evil."

Posters exhorting residents to "sweep away the black" are now ubiquitous in Chinese cities and such slogans have been scrawled in graffiti on village walls.

Among the crimes the campaign targets is using "religious connections at villages and townships to form mobs," according to implementation guidelines published late last year.

Among the crimes the campaign targets is using "religious connections at villages and townships to form mobs," according to implementation guidelines published late last year.

State media reports say 6,885 "black and evil" criminal organizations were taken down under the campaign as of January.

The "sweep away the black" campaign has also decimated power bases outside the Communist Party structure, including among religious communities.

The "sweep away the black" campaign has also decimated power bases outside the Communist Party structure, including among religious communities.

Hui communities are now told that unauthorized religious events or proselytizing are considered gatherings of "black" forces or "underworld forces."

Those unauthorized gatherings include Islamic schools run by Hui mosques, nearly all of which have been closed across China, particularly in Henan and Ningxia, according to residents in Henan, Ningxia, Yunnan and Gansu provinces.

Those unauthorized gatherings include Islamic schools run by Hui mosques, nearly all of which have been closed across China, particularly in Henan and Ningxia, according to residents in Henan, Ningxia, Yunnan and Gansu provinces.

NPR visited multiple former Islamic schools in September, several of which looked as if they had been cleared in a hurry — with dusty bedding piled on dormitory beds and chipped dishes and other kitchenware stacked haphazardly in corners.

All taught Arabic language and some Islamic doctrine, but some are run more like vocational schools or social welfare schools for students who might be otherwise ineligible or unable to afford an education.

Discarded kitchenware lies on the floor of Magou Mosque's Islamic School in Zhengzhou, Henan province. It was forced to close suddenly last April.

All taught Arabic language and some Islamic doctrine, but some are run more like vocational schools or social welfare schools for students who might be otherwise ineligible or unable to afford an education.

Discarded kitchenware lies on the floor of Magou Mosque's Islamic School in Zhengzhou, Henan province. It was forced to close suddenly last April.

"We barely taught any Islamic doctrine. It was about making sure these children were educated and would not become criminals or radicalized," said a former teacher surnamed Ma, who did not want her full name used for fear of political reprisal.

She had taught at an Islamic school in China's southwestern Yunnan province, which closed last April.

The school had stayed open despite orders in 2014 to expel all non-local students, particularly those having residency status in East Turkestan.

Ma was interrogated by police about the school's curriculum and whether the school was distributing drugs.

Ma was interrogated by police about the school's curriculum and whether the school was distributing drugs.

A common stereotype about ethnic minorities in China is that they sell drugs.

One of her colleagues was held incommunicado for three days and subjected to "thought work," or ideological training, Ma says.

Rewards for reporting suspicious behavior

In Ningxia's Tongxin county, a rare female-only Islamic school once renowned across China's northwest is being readied for demolition after it was shut down last April to make way for residential development.

"It is the government's policies. Who knows if they will change and when?" one of the school employees told NPR in hushed tones.

Rewards for reporting suspicious behavior

In Ningxia's Tongxin county, a rare female-only Islamic school once renowned across China's northwest is being readied for demolition after it was shut down last April to make way for residential development.

"It is the government's policies. Who knows if they will change and when?" one of the school employees told NPR in hushed tones.

She withheld her name because of the sensitivity of the matter.

Hui residents of Tongxin say local officials are now offering rewards between $700 and $2,820 to those who report suspicious religious behavior, such as proselytizing Islam or secretly teaching Islamic texts.

Hui residents of Tongxin say local officials are now offering rewards between $700 and $2,820 to those who report suspicious religious behavior, such as proselytizing Islam or secretly teaching Islamic texts.

Some male mosque attendees have begun wearing cloth masks covering the lower half of their faces when attending daily prayers to avoid identification.

Hui who have performed the Hajj, the Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, fall under particular suspicion. Last year, a group of about 20 pilgrims was detained in Saudi Arabia for having the wrong visas before being sent back to China, according to two people with friends in the group.

Hui who have performed the Hajj, the Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, fall under particular suspicion. Last year, a group of about 20 pilgrims was detained in Saudi Arabia for having the wrong visas before being sent back to China, according to two people with friends in the group.

Two Hui pilgrims with residency in East Turkestan were promptly sent to low-security East Turkestan detention facilities, according to the two people with friends in the group.

Unbearable pressure

NPR found evidence of significant pushback from Hui seeking to delay or avoid implementing religious restrictions.

Unbearable pressure

NPR found evidence of significant pushback from Hui seeking to delay or avoid implementing religious restrictions.

Hui say they drag out orders to demolish mosque domes, and some students continue to secretly attend religious classes, despite shuttered schools.

In Henan, NPR came across one mosque in the process of "renovating" its dome by building a cover to shield it from view, a compromise between local officials who demanded its removal and nearby Hui residents who refused to do so.

In Henan, NPR came across one mosque in the process of "renovating" its dome by building a cover to shield it from view, a compromise between local officials who demanded its removal and nearby Hui residents who refused to do so.

Mosque employees were also installing translucent plastic Arabic calligraphic inscriptions on the mosque walls – nearly invisible to all but true believers – to satisfy demands that they remove all Islamic symbols and Arabic script.

Hui Muslim men leave the Laohuasi mosque after Friday prayers in Linxia, Gansu province, in March 2018. Gansu so far has been able to keep most of its mosques intact while domes and minarets of mosques in other provinces have been altered or removed.

Hui Muslim men leave the Laohuasi mosque after Friday prayers in Linxia, Gansu province, in March 2018. Gansu so far has been able to keep most of its mosques intact while domes and minarets of mosques in other provinces have been altered or removed.

"The Hui people have been through one storm after another, and this is a storm that will pass," the mosque's imam told NPR.

"Who knows how the political environment may change? We do not want to spend money to tear our dome down, only to have to pay to build it up again next year."

Fearing the worst, some younger Hui Muslims are looking to leave China and have emigrated to Malaysia and Dubai in the past few years.

"The pressure on not just one's religious behavior, but how one lives one's daily life, is unbearable," said a young Hui man from Ningxia surnamed Tian, who did not want to use his full name for fear of being punished for talking to a foreign journalist.

Fearing the worst, some younger Hui Muslims are looking to leave China and have emigrated to Malaysia and Dubai in the past few years.

"The pressure on not just one's religious behavior, but how one lives one's daily life, is unbearable," said a young Hui man from Ningxia surnamed Tian, who did not want to use his full name for fear of being punished for talking to a foreign journalist.

"It weighs on your chest."

Ma Ju, a leader in a Sufi sect of Hui Muslims, left China for the United Arab Emirates in 2009 because of his outspoken criticism of religious restrictions in East Turkestan.

Ma Ju, a leader in a Sufi sect of Hui Muslims, left China for the United Arab Emirates in 2009 because of his outspoken criticism of religious restrictions in East Turkestan.

This year, he fled to the United States, because the UAE has an extradition agreement with China.

"The oppression I saw inflicted on Tibetans 20 years ago and the Uighurs 10 years ago, has finally reached my people," he says.

Ma Ju worries for his community back in China, especially now that technological tools like facial recognition make evading restrictions in China nearly impossible.

"You have legs, but you can't run away," he says.

"The oppression I saw inflicted on Tibetans 20 years ago and the Uighurs 10 years ago, has finally reached my people," he says.

Ma Ju worries for his community back in China, especially now that technological tools like facial recognition make evading restrictions in China nearly impossible.

"You have legs, but you can't run away," he says.

"You have money, but it's of no use. You have a heart, but you cannot lift yourself up. This is a new kind of repression."