A satirical cartoon of Lord Macartney kneeling before Emperor Qianlong and presenting his “gifts.”

IMPERIAL TWILIGHT

The Opium War and the End of China’s Last Golden Age

By Stephen R. Platt

Illustrated. 556 pp. Alfred A. Knopf. $35.

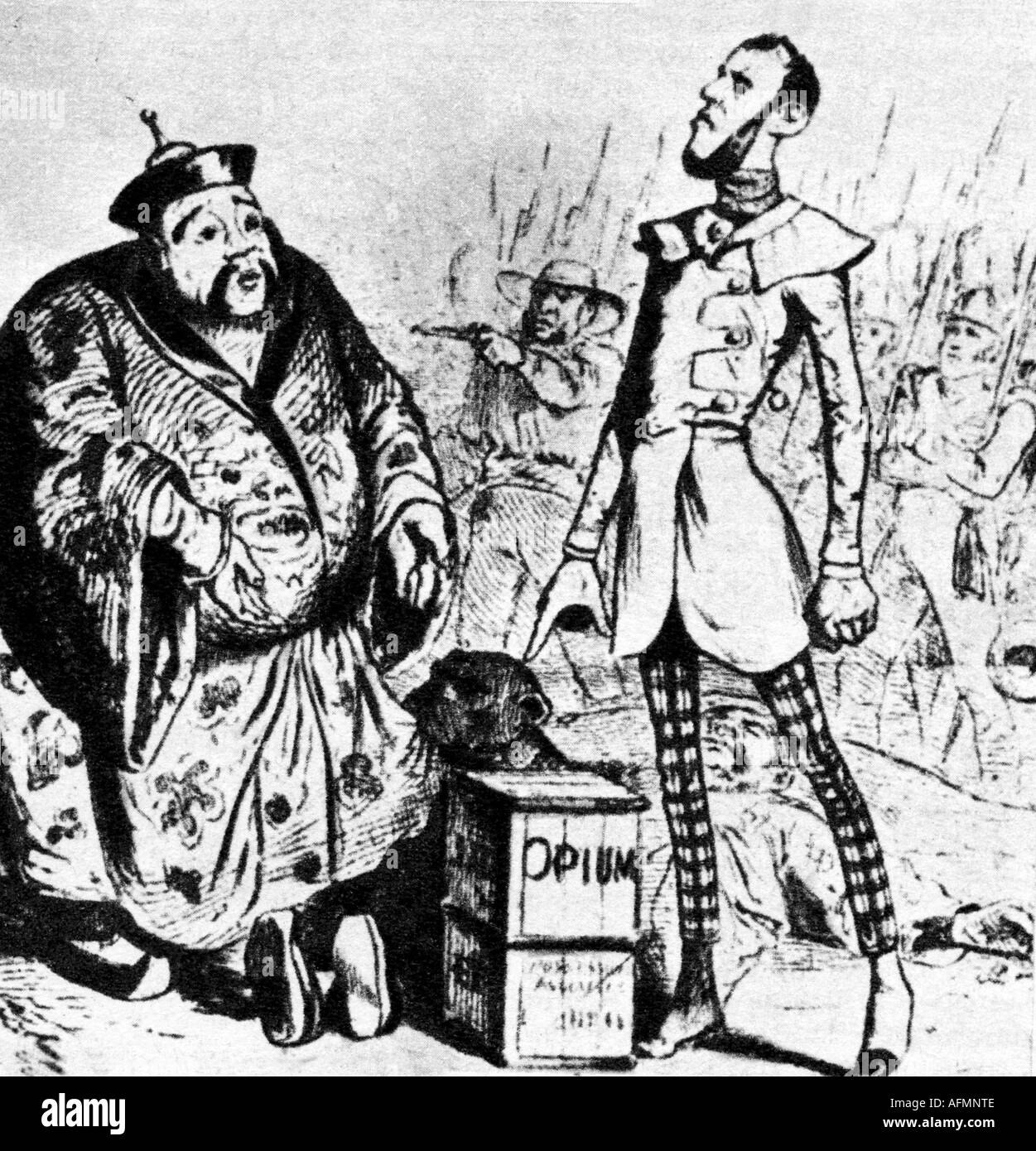

A century before its finest hour, the British Empire went through what may have been its darkest. After China declared a war on drugs in 1839, confiscating well over 1,000 tons of opium from dealers — mostly British — in Canton (modern Guangzhou), the cartels pressured their government back in London into demanding that Beijing repay them the full street value of their narcotics.

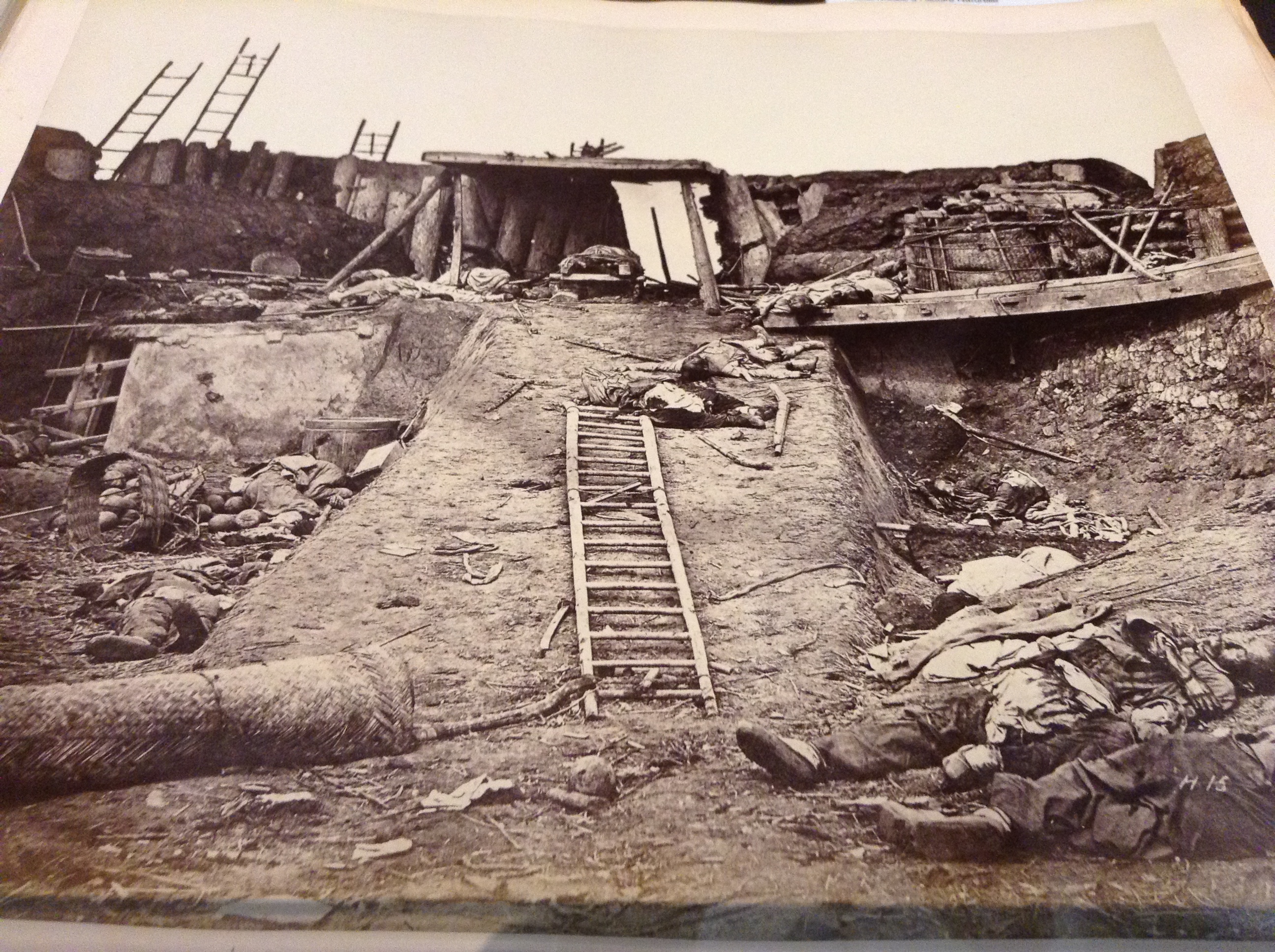

When the emperor refused, a squadron of Britain’s most up-to-date warships arrived in 1840 to brush aside the Celestial Empire’s junks and blast its coastal towns into ruins.

British troops slaughtered civilians up and down China’s coast.

“Many most barbarous things occurred disgraceful to our men,” one officer confessed.

Critics compared the opium trade to the recently banned slave trade.

The London government almost fell.

In China, the Opium War gradually came to be seen as the beginning of a century of humiliations at Western hands.

As the West’s entanglement with China has deepened since the 1990s, so too has fascination with the Opium War, and every China-watcher will want to read Stephen R. Platt’s fascinating and beautifully constructed new book.

As the West’s entanglement with China has deepened since the 1990s, so too has fascination with the Opium War, and every China-watcher will want to read Stephen R. Platt’s fascinating and beautifully constructed new book.

It is a worthy prequel to “Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom,” his fine account of the Taiping Rebellion, which claimed an estimated 20 million Chinese lives between 1850 and 1864.

Unlike most accounts of the Opium War, “Imperial Twilight” focuses not on the conflict itself but on its background, going back to the Chinese decision in the 1750s to restrict Western trade to the single port of Canton.

Unlike most accounts of the Opium War, “Imperial Twilight” focuses not on the conflict itself but on its background, going back to the Chinese decision in the 1750s to restrict Western trade to the single port of Canton.

The usual highlights, like Lord Macartney’s trade embassy of 1793, are all here, but so too is a parade of less well-known but equally important episodes and a procession of gloriously eccentric characters.

At one end, we have obsessive adventurers like Thomas Manning, who sneaked across the border from India into Tibet in 1811 armed with little more than a waist-length, jet-black beard and a dyspeptic Chinese interpreter — and yet managed to engineer an audience with the 6-year-old Dalai Lama.

Manning was overwhelmed: “His beautiful mouth” was “perpetually unbending into a graceful smile... I could have wept through strangeness of sensation... I was absorbed in reflections when I got home.”

At the other end are the red-in-tooth-and-claw British and American merchants in Canton who, forbidden to bring Western women with them, reverted to childhood, playing leapfrog at all hours of day and night.

Some of Platt’s villains, like the Scottish drug lords William Jardine and James Matheson, are worthy of soap opera.

Some of Platt’s villains, like the Scottish drug lords William Jardine and James Matheson, are worthy of soap opera.

Others, Britain’s Prime Minister Lord Melbourne, for example, take the banality of evil to new depths.

Worlds apart from Rufus Sewell’s urbane, ironic portrayal of Melbourne in the PBS television series “Victoria,” Platt’s Lord M unleashes the Opium War on China apparently with scarcely a second thought.

There is pathos aplenty as Charles Elliot, the British superintendent of trade in Canton, falls apart under Chinese pressure in 1839, eventually beginning to doubt his own sanity.

Good men do bad things, roads to hell are paved with good intentions and golden opportunities are missed.

In short, “Imperial Twilight” is a ripping yarn.

And yet Platt’s story also has a thesis, even if he makes it explicit only in his final few pages.

And yet Platt’s story also has a thesis, even if he makes it explicit only in his final few pages.

“It is important to remember just how arbitrary and unexpected the outcome of this era really was,” he says.

The war was “not part of some long-term British imperial plan. … Neither did it result from some inevitable clash of civilizations.”

Rather, “Imperial Twilight” is overflowing with individuals precisely because it is the individuals who drove everything.

In the age-old debate over the historical roles of Very Important Persons and Vast Impersonal Forces, Platt comes down firmly on the side of the people.

“If Charles Elliot had not let his panic get the best of him when he so dramatically overreacted to Lin Zexu’s threats,” Platt speculates.

“If Charles Elliot had not let his panic get the best of him when he so dramatically overreacted to Lin Zexu’s threats,” Platt speculates.

“Or if Lin Zexu himself had been more open to working with, rather than against, Elliot; if they had cooperated on their shared interest in bringing the British opium smugglers under control. Or if just five members of the House of Commons had voted differently in the early hours of April 10, 1840 — we might be looking back on very different lessons from this era.”

And just in case we misunderstand, Platt closes with a coda on the business relationship between the Chinese merchant Houqua and the American John Murray Forbes, which “had always been informal, based on trust and affection.”

Everything could have been different — and better.

“Imperial Twilight” is a masterpiece of the “If Only” school of history, which holds out the tantalizing prospect of a world that, with the right choices, could be made perfect.

“Imperial Twilight” is a masterpiece of the “If Only” school of history, which holds out the tantalizing prospect of a world that, with the right choices, could be made perfect.

Edmund Morgan’s magnificent “American Slavery, American Freedom” is a classic of this kind, insistently hinting that if a few people in 17th-century Virginia had chosen differently, the cancers of slavery and racism would not have entered America’s bloodstream.

So too, in a different way, is Niall Ferguson’s “The Pity of War,” arguing that Britain could have avoided entering World War I — in which case there would have been a European war but not a global one, the British Empire would have survived, and fascism and Communism would never have taken off.

In the right hands, like Platt’s, this produces superb history, explaining why the actors acted as they did while also showing that they did not have to do so — and could in fact have made a better world. And yet too often one ends up feeling that the authors’ own narratives do not quite bear out their theory, and that the Very Important Persons’ choices are always constrained by Vast Impersonal Forces that they rarely understand, let alone control.

In this case, Britain’s industrial revolution was transforming the balance of global power in the early 19th century.

In the right hands, like Platt’s, this produces superb history, explaining why the actors acted as they did while also showing that they did not have to do so — and could in fact have made a better world. And yet too often one ends up feeling that the authors’ own narratives do not quite bear out their theory, and that the Very Important Persons’ choices are always constrained by Vast Impersonal Forces that they rarely understand, let alone control.

In this case, Britain’s industrial revolution was transforming the balance of global power in the early 19th century.

It was not inevitable that Britons would use violence to exploit this, but the revolution constantly threw up situations where violence was an option.

We might think of each crisis as a roll of the dice.

In 1802, war between Britain and France almost spilled over into China.

In 1808, British marines seized Macao, but withdrew peacefully.

Tempers flared again in 1814, and in 1816 the H.M.S. Alceste fired on a Chinese fort, killing a reported 47 soldiers.

None of these incidents had anything to do with opium, but in 1831 the drug dealers tried to provoke a war when Chinese officials trampled their shrub garden and insulted a portrait of King George IV.

It was not written in stone that Britain and China would get the particular war they did.

It was not written in stone that Britain and China would get the particular war they did.

Cooler heads could have prevailed in 1839, although by the same token, hotter heads could have prevailed at any time since 1802.

And even if 1839 had passed off peacefully, crises would have just kept coming.

British merchants would have kept pushing to open China (in the late 1850s, they did bring on a second war).

Compromises would not have satisfied the Jardines and Mathesons, and the likelihood that no British government would ever have decided that violence was its least bad option seems vanishingly small.

Stephen Platt has written an enthralling account of the run-up to war between Britain and China during a century in which wealth and power were shifting inexorably from East to West.

Stephen Platt has written an enthralling account of the run-up to war between Britain and China during a century in which wealth and power were shifting inexorably from East to West.

But if this history holds a lesson today — as wealth and power shift equally inexorably back from West to East — it is surely the same one that Karl Marx identified just a decade after the Opium War, that men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please.