China Expands Travel Restrictions to 2 More Cities as Outbreak Grows

- The authorities enacted strict travel bans for the central Chinese cities of Huanggang, Ezhou and Wuhan, collectively home to nearly 20 million people.

- At least 17 people have died and more than 570 have been sickened by a mysterious illness.

By The New York Times

In addition to canceling flights and trains, the authorities also shuttered movie theaters, cafes and other public spaces.

Police officers guarding an entrance to the closed Hankou Railway Station in Wuhan, China, on Thursday.

The authorities ban travel from three cities at center of outbreak, affecting millions.

The authorities expanded travel restrictions to two central Chinese cities near Wuhan, the epicenter of a mysterious outbreak of coronavirus, hours after announcing that 17 people had died and more than 570 had contracted the disease.

The restrictions on train and other forms of travel will apply to tens of millions of people and come just days before the Lunar New Year holiday, when hundreds of millions of people travel around and out of the country.

The Chinese authorities on Thursday morning closed off Wuhan — a major port city of more than 11 million people and the center of a pneumonia-like virus that has spread halfway around the world — by canceling flights and trains leaving the city, and suspending buses, subways and ferries within it.

By evening, officials planned to close off Huanggang, a city of seven million about 30 miles east of Wuhan, and shut rail stations in the nearby city of Ezhou, which has about one million residents.

In Huanggang, public transportation and departing trains would were to stop service at midnight. Residents would not be allowed to leave the city without special permission, according to a government statement.

The authorities expanded travel restrictions to two central Chinese cities near Wuhan, the epicenter of a mysterious outbreak of coronavirus, hours after announcing that 17 people had died and more than 570 had contracted the disease.

The restrictions on train and other forms of travel will apply to tens of millions of people and come just days before the Lunar New Year holiday, when hundreds of millions of people travel around and out of the country.

The Chinese authorities on Thursday morning closed off Wuhan — a major port city of more than 11 million people and the center of a pneumonia-like virus that has spread halfway around the world — by canceling flights and trains leaving the city, and suspending buses, subways and ferries within it.

By evening, officials planned to close off Huanggang, a city of seven million about 30 miles east of Wuhan, and shut rail stations in the nearby city of Ezhou, which has about one million residents.

In Huanggang, public transportation and departing trains would were to stop service at midnight. Residents would not be allowed to leave the city without special permission, according to a government statement.

In Ezhou, all rail stations were to be closed.

In Wuhan, residents said that a sense of fear was growing as the city went into lockdown.

The new virus, which first emerged at the end of December, has killed at least 17 people and sickened more than 570, including in Taiwan, Japan, Thailand, South Korea and the United States.

In Wuhan, residents said that a sense of fear was growing as the city went into lockdown.

The new virus, which first emerged at the end of December, has killed at least 17 people and sickened more than 570, including in Taiwan, Japan, Thailand, South Korea and the United States.

It has raised the specter of a repeat of the SARS epidemic, which broke out in China in 2002 and 2003 and spread rapidly while officials obscured the seriousness of the crisis.

That virus eventually killed more than 800 people worldwide.

Roughly 30,000 people fly out of Wuhan on an average day, according to air traffic data.

Roughly 30,000 people fly out of Wuhan on an average day, according to air traffic data.

Many more leave using ground transportation like trains and cars.

The city is the hub of industry and commerce in central China, home to the region’s biggest airport and deepwater port.

The sudden restrictions could upend the travel plans of millions of Chinese citizens, who travel in huge numbers during the Lunar New Year holiday, which begins on Friday.

The sudden restrictions could upend the travel plans of millions of Chinese citizens, who travel in huge numbers during the Lunar New Year holiday, which begins on Friday.

The government said it would close Wuhan’s airport and train stations to departures, and it urged residents not to leave the city unless they had an urgent reason to do so.

Residents are nervous and angry.

A supermarket in Wuhan, on Thursday.

Residents are nervous and angry.

A supermarket in Wuhan, on Thursday.

Across Wuhan on Thursday, residents — some wearing masks, some sniffing or coughing — visited hospitals and clinics seeking treatment.

In interviews with a New York Times correspondent in the city, some said they were angry about the sudden lockdown.

Others said they were confused by the restrictions.

Outside the Wuhan No. 3 Hospital, Yang Lin, said she had come to the hospital to see if a sniffling cold she had might be the coronavirus.

Outside the Wuhan No. 3 Hospital, Yang Lin, said she had come to the hospital to see if a sniffling cold she had might be the coronavirus.

She said that after a quick check, the doctors told her not to worry.

But she was not reassured.

“They said it was just a common cold, and told me to get some medicine and go home,” Ms. Yang, 28, said.

“They said it was just a common cold, and told me to get some medicine and go home,” Ms. Yang, 28, said.

“But how am I to know? They didn’t even take my temperature. It’s just not responsible.”

The outbreak is testing Wuhan’s health care system.

The outbreak is testing Wuhan’s health care system.

Several Wuhan residents said on social media websites that they had gone from hospital to hospital, waiting in lines for hours, only to be sent home with medicine and instructions to seek further treatment later if symptoms persisted in a few days.

“The government did not fulfill its duty,” Du Hanrong, 56, a retiree, said by telephone.

“The government did not fulfill its duty,” Du Hanrong, 56, a retiree, said by telephone.

“They just are doing things hastily and carelessly.”

Doctors told some patients that there was a shortage of hospital beds as well as testing kits, according to posts on Chinese social media sites.

Cheng Shidong, a doctor at the Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, said in an interview that his hospital had set up 100 beds to receive infected patients, but that it didn’t have enough protective material, such as masks and suits, for the medical staff.

In Wuhan, Ms. Yang said that while she was in a pharmacy buying medicine, another person complained that he thought he had the coronavirus but had not been isolated.

Doctors told some patients that there was a shortage of hospital beds as well as testing kits, according to posts on Chinese social media sites.

Cheng Shidong, a doctor at the Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, said in an interview that his hospital had set up 100 beds to receive infected patients, but that it didn’t have enough protective material, such as masks and suits, for the medical staff.

In Wuhan, Ms. Yang said that while she was in a pharmacy buying medicine, another person complained that he thought he had the coronavirus but had not been isolated.

The city’s medical system, especially its smaller hospitals, seems unprepared for the influx of patients, she said.

“I’m willing to accept that we have to stay in Wuhan, O.K., but the medical care needs to keep up,” she said.

“I’m willing to accept that we have to stay in Wuhan, O.K., but the medical care needs to keep up,” she said.

“You shouldn’t tell us we can’t leave, and then give us second-rate medical care. That’s unfair.”

Who are the victims?

Health workers wear protective suits at the Zhongnan Hospital in Wuhan, China, on Wednesday.

Who are the victims?

Health workers wear protective suits at the Zhongnan Hospital in Wuhan, China, on Wednesday.

China’s health commission, which has tightly controlled news about the toll of the outbreak, released on Thursday its most detailed list of the people who have died of the disease.

The first 17 people were largely older men, many with underlying health problems.

The first 17 people were largely older men, many with underlying health problems.

All died in Hubei Province, which includes the city of Wuhan.

The first confirmed death was a 61-year-old man who went to a hospital in Wuhan on December 27, weak with a fever and a cough.

The first confirmed death was a 61-year-old man who went to a hospital in Wuhan on December 27, weak with a fever and a cough.

He was transferred to another hospital as his condition worsened, and he was later attached to a machine that helped oxygenate his blood.

But his condition worsened, and he died on Jan. 9.Of the first 17 deaths, 13 were men and four were women, officials said.

The youngest victim was a 48-year-old woman identified only by her surname, Yin, who died on Monday.

The oldest were two 89-year-old men who died on Saturday and Sunday.

Many had underlying conditions like cirrhosis of the liver, hypertension, diabetes and Parkinson’s disease.

Many had underlying conditions like cirrhosis of the liver, hypertension, diabetes and Parkinson’s disease.

Most had gone to the hospital with a fever and a cough, though at least three had no fever when they were admitted, according to the health commission.

While a full picture of the virus is still unknown, medical experts found some positive signs in the fact that the disease did not appear to be killing young and otherwise healthy people.It was a somewhat reassuring sign that “the majority of fatal cases are elderly and/or have a chronic disease that would increase their susceptibility to infectious diseases,” said Dr. W. Ian Lipkin, an epidemiologist at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University in New York.

While a full picture of the virus is still unknown, medical experts found some positive signs in the fact that the disease did not appear to be killing young and otherwise healthy people.It was a somewhat reassuring sign that “the majority of fatal cases are elderly and/or have a chronic disease that would increase their susceptibility to infectious diseases,” said Dr. W. Ian Lipkin, an epidemiologist at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University in New York.

‘I feel extremely powerless,’ says a SARS expert, raising an alarm.

Travelers arrive on Thursday at a nearly deserted train station in Wuhan.

In an unusually blunt interview, Dr. Guan Yi, a professor of infectious diseases in Hong Kong and expert on SARS, criticized the authorities in Wuhan for acting too slowly and obstructing his efforts to investigate the outbreak.

Dr. Guan, who helped successfully identify the coronavirus that caused SARS during the 2002-2003 outbreak in China, told the influential Chinese magazine Caixin that he was deeply frustrated by the city government’s response to the spread of the virus.

He and his team had visited Wuhan on Tuesday hoping that they could track the animal that was the source of the coronavirus but were shocked to find that residents at a market were not taking any precautions or wearing masks.

Dr. Guan, who helped successfully identify the coronavirus that caused SARS during the 2002-2003 outbreak in China, told the influential Chinese magazine Caixin that he was deeply frustrated by the city government’s response to the spread of the virus.

He and his team had visited Wuhan on Tuesday hoping that they could track the animal that was the source of the coronavirus but were shocked to find that residents at a market were not taking any precautions or wearing masks.

No special measures were in place at the airport to disinfect surfaces and floors, either.

This showed that the city government was being complacent despite the urgent orders handed down by Beijing, he said.

“I thought at the time, we had to be in a ‘state of war’, but how come the alarm has not been raised?” he told Caixin.

“I thought at the time, we had to be in a ‘state of war’, but how come the alarm has not been raised?” he told Caixin.

“Poor citizens, they were still preparing to ring in the New Year in peace and had no sense about the epidemic.”

He also criticized the local authorities for disinfecting the market where many infections had been traced to, saying that made it difficult for researchers to investigate where the virus came from.

“I consider myself a veteran in battles,” he said, citing his experience with bird flu, SARS, and other outbreaks.

He also criticized the local authorities for disinfecting the market where many infections had been traced to, saying that made it difficult for researchers to investigate where the virus came from.

“I consider myself a veteran in battles,” he said, citing his experience with bird flu, SARS, and other outbreaks.

“But with this Wuhan pneumonia, I feel extremely powerless.”

What is a coronavirus and why is it so dangerous?

Paramedics taking a man believed to be Hong Kong’s first coronavirus patient to a hospital on Wednesday.

Paramedics taking a man believed to be Hong Kong’s first coronavirus patient to a hospital on Wednesday.

Coronaviruses are named for the spikes that protrude from their membranes, which resemble the sun’s corona.

They can infect both animals and people, and cause illnesses of the respiratory tract, ranging from the common cold to severe conditions like SARS, which sickened thousands of people around the world — and killed nearly 800 — during a 2003 outbreak.

Symptoms of infection include a high fever, difficulty breathing and lung lesions.

Symptoms of infection include a high fever, difficulty breathing and lung lesions.

Milder cases may resemble the flu or a bad cold, making detection very difficult.

The incubation period — the time from exposure to the onset of symptoms — is believed to be about two weeks.

Little is known about who is most at risk.

Little is known about who is most at risk.

Some of the nine patients who have died also suffered other illnesses.

Chinese worry the government is underreporting cases.

A hospital worker washes the entrance to the Wuhan Medical Treatment Center, where some infected with a new virus were being treated.

There are growing concerns that the Chinese authorities are underreporting the number of people who are ill with the virus.

Relatives of patients say that hospitals, strapped for resources as they deal with an influx of patients, are turning sick people away or refusing to test them for the coronavirus.Many people remain skeptical of the government’s official statistics, with memories of the effort to cover up the severity of the SARS outbreak in 2003 still fresh.

In Wuhan, Kyle Hui, an architect from Shanghai, said that doctors at Tongji Hospital declined to test his stepmother for the virus, even though she was showing symptoms like a cough and a fever.

In Wuhan, Kyle Hui, an architect from Shanghai, said that doctors at Tongji Hospital declined to test his stepmother for the virus, even though she was showing symptoms like a cough and a fever.

She died on Jan. 15 of “severe pneumonia,” according to a copy of her death certificate.Mr. Hui said that hospital workers treated his stepmother as if she had the coronavirus, wearing hazmat suits.

After she died, the hospital instructed the family to cremate the body immediately.

Mr. Hui said that after her death, doctors informed the family that they suspected his stepmother had the coronavirus.

“I’m very sad my stepmother left without any dignity,” Mr. Hui said during an interview this week in a cafe in Wuhan.

“I’m very sad my stepmother left without any dignity,” Mr. Hui said during an interview this week in a cafe in Wuhan.

“There was no time to say goodbye.”

Chinese state media plays down the crisis.

Health officials in Beijing take passengers’ temperatures as they arrive on flights from Wuhan on Wednesday.

Chinese state media plays down the crisis.

Health officials in Beijing take passengers’ temperatures as they arrive on flights from Wuhan on Wednesday.

A sense of crisis is spreading through China as more people fall ill to the deadly virus.

But you wouldn’t know it reading the front pages of China’s official newspapers.

As China grapples with one of its most serious public health crises in years, the ruling Communist Party’s most important news outlets seem oblivious to the emergency.

On Thursday, the front page of the People’s Daily featured stories about Chinese dictator Xi Jinping “visiting and comforting” villagers in Yunnan, a southwestern province, ahead of the Lunar New Year Holiday, describing a “warm and peaceful” scene.

As China grapples with one of its most serious public health crises in years, the ruling Communist Party’s most important news outlets seem oblivious to the emergency.

On Thursday, the front page of the People’s Daily featured stories about Chinese dictator Xi Jinping “visiting and comforting” villagers in Yunnan, a southwestern province, ahead of the Lunar New Year Holiday, describing a “warm and peaceful” scene.

A photo showed New Year’s revelers aboard a train, smiling and snapping photos.

On Wednesday, China Central Television, the state broadcaster, treated the outbreak as a footnote in its evening newscast, one of the most watched television programs in China, instead focusing on Xi’s talks with world leaders.

While more commercially focused outlets, such as Caixin, a financial magazine, and the Beijing News, a newspaper, are covering the crisis extensively, the party’s flagship news outlets have been quiet.

Experts said Xi Jinping was trying to prevent a sense of panic and to limit criticism of the party’s response.“The top priority will be to keep coverage from asking more probing questions about how China’s institutions have responded, questions that might lead to criticism of the government,” said David Bandurski, co-director of the China Media Project.

On Wednesday, China Central Television, the state broadcaster, treated the outbreak as a footnote in its evening newscast, one of the most watched television programs in China, instead focusing on Xi’s talks with world leaders.

While more commercially focused outlets, such as Caixin, a financial magazine, and the Beijing News, a newspaper, are covering the crisis extensively, the party’s flagship news outlets have been quiet.

Experts said Xi Jinping was trying to prevent a sense of panic and to limit criticism of the party’s response.“The top priority will be to keep coverage from asking more probing questions about how China’s institutions have responded, questions that might lead to criticism of the government,” said David Bandurski, co-director of the China Media Project.

A New York Times reporter travels to the epidemic’s ground zero.

Chris Buckley, our chief China correspondent, headed to Wuhan from Beijing to cover the outbreak. He is sending live dispatches from his trip.

9:25 A.M. — BEIJING

At the Beijing West Railway Station on Thursday morning there were noticeably more people wearing masks than have been seen around the city in recent days.

Still, the number of travelers heading out for the Lunar New Year is still sizable.

This is not the empty ghost city that Beijing became during the SARS epidemic of 2003.

Hundreds of people lined up to take a train that passes through Wuhan and other cities on the way to Hong Kong.

Almost all wore masks.

11 A.M. — ABOARD THE G79 HIGH SPEED TRAIN

The G79 high speed train from Beijing to Hong Kong, which stops in Wuhan, was crowded with holiday passengers.

11 A.M. — ABOARD THE G79 HIGH SPEED TRAIN

The G79 high speed train from Beijing to Hong Kong, which stops in Wuhan, was crowded with holiday passengers.

But few seemed to have plans to get off in Wuhan.

The train was a hubbub of conversation, much of it about the deadly coronavirus and the lockdown around Wuhan.

Guo Jing, a worker from northeast China, was headed with two friends for a holiday in Macau.

Guo Jing, a worker from northeast China, was headed with two friends for a holiday in Macau.

After some hesitation, they had taken off their masks.

“They’re too uncomfortable inside,” Mr. Guo said.

“My view is we have to be careful but not panic. If you’re the panicky type, then you wouldn’t be on this train.”

Chris Buckley 储百亮

✔@ChuBailiang

Time to get back onto Twitter. I’m about to arrive in Wuhan to see how the city is coping under the lockdown and the menace of the coronavirus. Also follow live updates at the Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/23/world/asia/china-coronavirus.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share …

1,821

6:47 AM - Jan 23, 2020

1:37 P.M. — ABOARD THE G79 HIGH SPEED TRAIN

Half an hour out from Wuhan, the train is quite crowded with passengers, most of whom are wearing masks.

I haven’t been able to find any who say they are ending their journey at Wuhan, and when I explain that I’m getting off there the reactions vary from advice — wear masks, don’t go, drink lots of water — to mordant jokes that I may be there a long time.

“You should know that they probably won’t let people out until the New Year holiday is over,” said one woman, who would only give her family name, Yang.

Chris Buckley 储百亮

✔@ChuBailiang

Time to get back onto Twitter. I’m about to arrive in Wuhan to see how the city is coping under the lockdown and the menace of the coronavirus. Also follow live updates at the Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/23/world/asia/china-coronavirus.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share …

1,821

6:47 AM - Jan 23, 2020

1:37 P.M. — ABOARD THE G79 HIGH SPEED TRAIN

Half an hour out from Wuhan, the train is quite crowded with passengers, most of whom are wearing masks.

I haven’t been able to find any who say they are ending their journey at Wuhan, and when I explain that I’m getting off there the reactions vary from advice — wear masks, don’t go, drink lots of water — to mordant jokes that I may be there a long time.

“You should know that they probably won’t let people out until the New Year holiday is over,” said one woman, who would only give her family name, Yang.

I had expected that there might be checks on the train, or guards checking people who planned to get off at Wuhan.

But not so far.

2:29 P.M. — WUHAN

Wuhan Railway Station, usually thronging with people in the days before the Lunar New Year holiday, is very empty.

An announcement playing on a loop over the speakers tells the few people here that residents cannot leave the city and the station is temporarily closed.

2:29 P.M. — WUHAN

Wuhan Railway Station, usually thronging with people in the days before the Lunar New Year holiday, is very empty.

An announcement playing on a loop over the speakers tells the few people here that residents cannot leave the city and the station is temporarily closed.

But there is, so far at least, no extraordinary security around the station.

There was a fever detector at the exit from the train platform, but I’ve seen no other steps to check people.

Many residents tried to leave the city.

The announcement that the city of Wuhan would be temporarily sealed off from the outside world starting at 10 a.m. on Thursday came while most residents were asleep at 2 a.m.

Some decided to flee the city.

Residents were seen hauling their luggage to a train station in the early hours before the citywide lockdown took effect, the Chinese news outlet Caixin reported.

Many residents tried to leave the city.

The announcement that the city of Wuhan would be temporarily sealed off from the outside world starting at 10 a.m. on Thursday came while most residents were asleep at 2 a.m.

Some decided to flee the city.

Residents were seen hauling their luggage to a train station in the early hours before the citywide lockdown took effect, the Chinese news outlet Caixin reported.

Several people said they would buy tickets for any destination as long as they could leave Wuhan, the magazine reported.

Lines of passengers in masks and down jackets, lugging suitcases, formed outside the major Hankou railway station just 20 minutes before the cutoff time, a live video by media outlet The Paper showed.

Han Zhen and Wang Mengkai, two migrant workers from Henan Province, said they had rushed to the railway station in order to leave on Wednesday night, but missed the last train out.

Both said they were frustrated by the sudden lockdown and were scrambling to find a way home.

“It’s serious but not that serious,” said Mr. Wang, who works in an electronics parts factory.

Lines of passengers in masks and down jackets, lugging suitcases, formed outside the major Hankou railway station just 20 minutes before the cutoff time, a live video by media outlet The Paper showed.

Han Zhen and Wang Mengkai, two migrant workers from Henan Province, said they had rushed to the railway station in order to leave on Wednesday night, but missed the last train out.

Both said they were frustrated by the sudden lockdown and were scrambling to find a way home.

“It’s serious but not that serious,” said Mr. Wang, who works in an electronics parts factory.

“We’re trying to figure out how we can get home. If we can’t get out on a train, we’ll try putting together a car with a driver.”

Asked if they were motivated to leave by fear of the virus, Mr. Han said: “No, we are not scared.”

“It’s the New Year, we just have to go home,” he added.

Asked if they were motivated to leave by fear of the virus, Mr. Han said: “No, we are not scared.”

“It’s the New Year, we just have to go home,” he added.

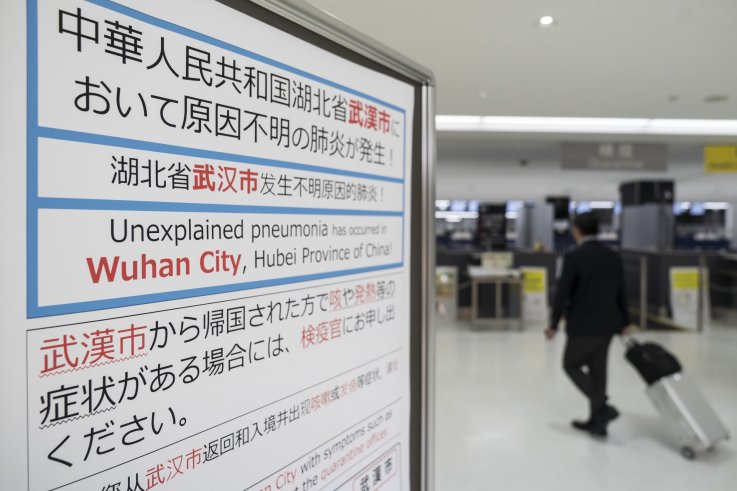

A passenger walks past a notice for passengers from Wuhan, China displayed near a quarantine station at Narita airport on January 17, 2020 in Narita, Japan. Japan's Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has confirmed its first case of pneumonia infected with a new coronavirus from Wuhan City, China.

A passenger walks past a notice for passengers from Wuhan, China displayed near a quarantine station at Narita airport on January 17, 2020 in Narita, Japan. Japan's Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has confirmed its first case of pneumonia infected with a new coronavirus from Wuhan City, China.

Chinese dictator Xi Jinping appears on screen during an exhibition this fall marking 70 years of Communist rule.

Chinese dictator Xi Jinping appears on screen during an exhibition this fall marking 70 years of Communist rule.