BY TOM O'CONNOR

The United States has accused China of preventing Southeast Asian countries from accessing trillions of dollars worth of untapped oil and gas reserves in the South China Sea as the Pentagon planned to hold its first exercise with regional powers near the strategic region.

In a press statement, State Department spokesperson Morgan Ortagus said Thursday that the "United States is deeply concerned that China is continuing its interference with Vietnam's longstanding oil and gas activities in Vietnam's Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) claim" following recent incursions there by Chinese survey ship Haiyang Dizhi 8 and an armed escort.

Beijing has laid vast claims to the South China Sea and does not recognize boundaries established there by a number of Southeast Asian nations who are supported by the U.S.

The most recent incident occurred last week near Vanguard Bank, a Vietnam-administered outpost in the Spratly Islands, and Ortagus attributed the move to China "pressuring Vietnam over its work with a Russian energy firm and other international partners."

"China's actions undermine regional peace and security, impose economic costs on Southeast Asian states by blocking their access to an estimated $2.5 trillion in unexploited hydrocarbon resources, and demonstrate China's disregard for the rights of countries to undertake economic activities in their EEZs, under the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention, which China ratified in 1996," Ortagus said.

Chinese survey vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8 conducts research on behalf of the Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey in this photo shared July 25, 2018. The ship once again entered what Vietnam's exclusive economic zone near Vanguard Bank of South China Sea's Spratly Islands on August 13 of this year.

Chinese survey vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8 conducts research on behalf of the Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey in this photo shared July 25, 2018. The ship once again entered what Vietnam's exclusive economic zone near Vanguard Bank of South China Sea's Spratly Islands on August 13 of this year.

Washington has signed, but not ratified the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention, though it justified sending warships through Beijing-claimed waters in the South China Sea by citing "freedom of navigation" operations outlined in the deal.

"China's actions undermine regional peace and security, impose economic costs on Southeast Asian states by blocking their access to an estimated $2.5 trillion in unexploited hydrocarbon resources, and demonstrate China's disregard for the rights of countries to undertake economic activities in their EEZs, under the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention, which China ratified in 1996," Ortagus said.

Chinese survey vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8 conducts research on behalf of the Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey in this photo shared July 25, 2018. The ship once again entered what Vietnam's exclusive economic zone near Vanguard Bank of South China Sea's Spratly Islands on August 13 of this year.

Chinese survey vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8 conducts research on behalf of the Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey in this photo shared July 25, 2018. The ship once again entered what Vietnam's exclusive economic zone near Vanguard Bank of South China Sea's Spratly Islands on August 13 of this year.Washington has signed, but not ratified the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention, though it justified sending warships through Beijing-claimed waters in the South China Sea by citing "freedom of navigation" operations outlined in the deal.

China has responded by scrambling military ships and aircraft to intercept the U.S. vessels in the resource-rich region.

While China may have backed Vietnam's communist revolutionaries in their victory over U.S. and allied local forces decades ago, Beijing and Hanoi quickly became rivals and engaged in deadly border clashes, including near the Spratly Island, lasting up until the 1990s.

While China may have backed Vietnam's communist revolutionaries in their victory over U.S. and allied local forces decades ago, Beijing and Hanoi quickly became rivals and engaged in deadly border clashes, including near the Spratly Island, lasting up until the 1990s.

In 1995, Vietnam and the U.S. normalized their relations, putting pressure on China as the region's geopolitical dynamics shifted.

As the U.S. began to increasingly assert its own presence in the South China Sea, it has sought to push back on China there, exploiting territorial tensions between Beijing and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), a 10-nation grouping of which Vietnam was a part.

As the U.S. began to increasingly assert its own presence in the South China Sea, it has sought to push back on China there, exploiting territorial tensions between Beijing and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), a 10-nation grouping of which Vietnam was a part.

Washington sided with Hanoi in 2014 when China moved its Hai Yang Shi You 981 oil rig near the disputed Paracel Islands and sank a Vietnamese fishing vessel amid a standoff there.

Last year, the U.S. sent a historic message to China by sending Nimitz-class supercarrier USS Carl Vinson to dock in Vietnam in March.

Last year, the U.S. sent a historic message to China by sending Nimitz-class supercarrier USS Carl Vinson to dock in Vietnam in March.

In May, the U.S. disinvited China from the Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise involving Vietnam and several other ASEAN states over Beijing's increased militarization of the Spratly Islands.

The U.S. also began planning joint drills with ASEAN, but it was China that secured an exercise alongside the regional collective months later in October.

The U.S. also began planning joint drills with ASEAN, but it was China that secured an exercise alongside the regional collective months later in October.

That same month, then-Defense Secretary James Mattis confirmed that a U.S.-ASEAN exercise was still in the works and on both The Bangkok Post and Nikkei Asian Review reported Thursday that the maneuvers were set to begin early next month in Thailand.

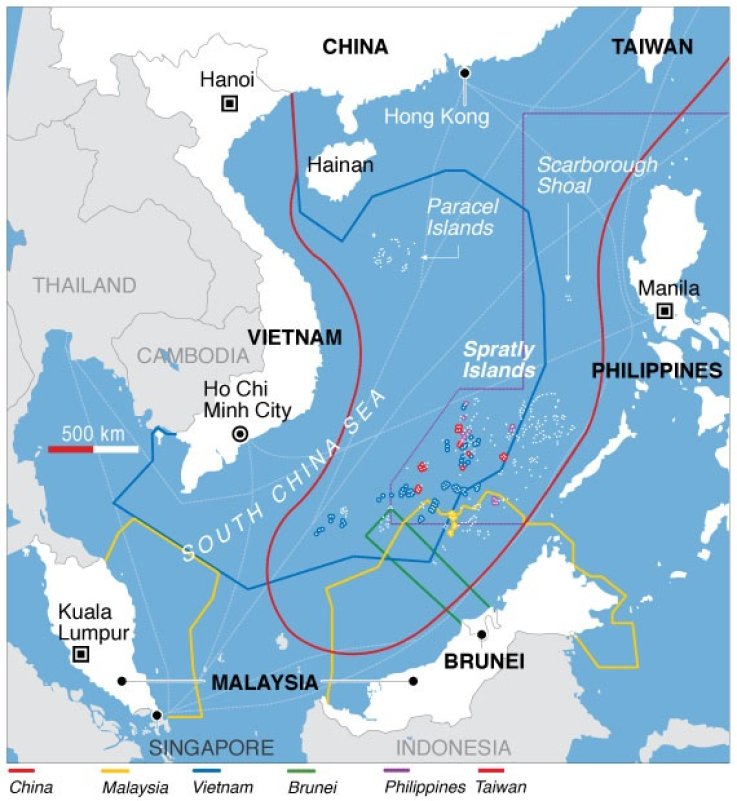

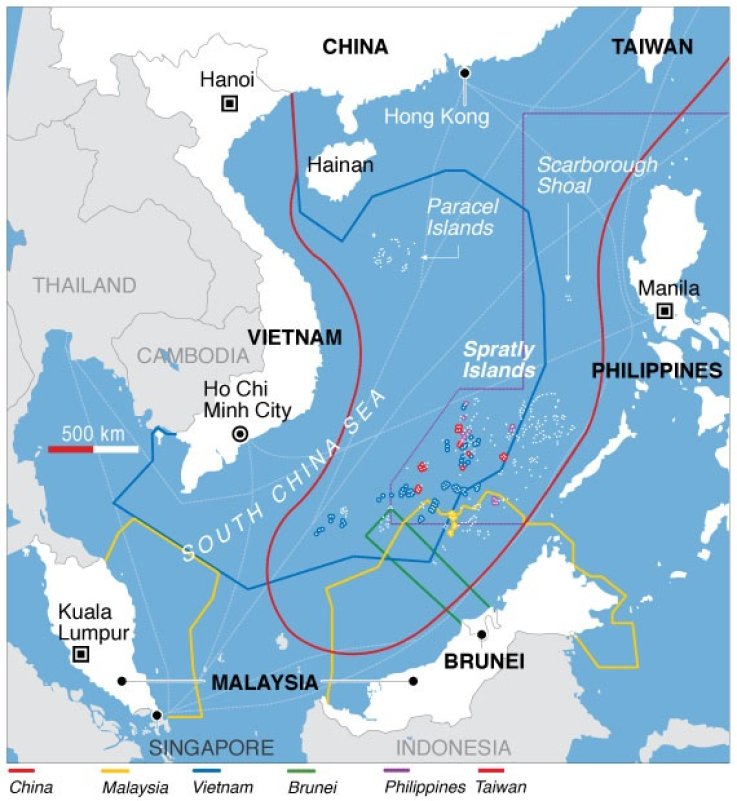

A map created July 30, 2012 details the multinational, overlapping territorial disputes involving Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam in the South China Sea. Many of these countries, especially China, have expanded their presence on contested land masses known as the Spratly Islands and an incident on August 13 of this year took place on the westernmost stretch of reefs.

Tensions in the South China Sea add to an array of issues already putting a major strain on ties between the world's top two economies.

President Donald Trump and Chinese Xi Jinping are embroiled in a multibillion-dollar trade war of tit-for-tat tariffs with Vietnam finding itself right in the middle of the feuding powerhouses.

Beijing has also repeatedly accused Washington of interfering in its internal affairs, both in the ongoing protests that U.S. officials and politicians have expressed support for in the semi-autonomous city of Hong Kong and in a recent $8 billion arms sale involving F-16V fighters jets to Taiwan, an independent island nation also claimed by Beijing.

Beijing has also repeatedly accused Washington of interfering in its internal affairs, both in the ongoing protests that U.S. officials and politicians have expressed support for in the semi-autonomous city of Hong Kong and in a recent $8 billion arms sale involving F-16V fighters jets to Taiwan, an independent island nation also claimed by Beijing.