BY AMY GUNIA

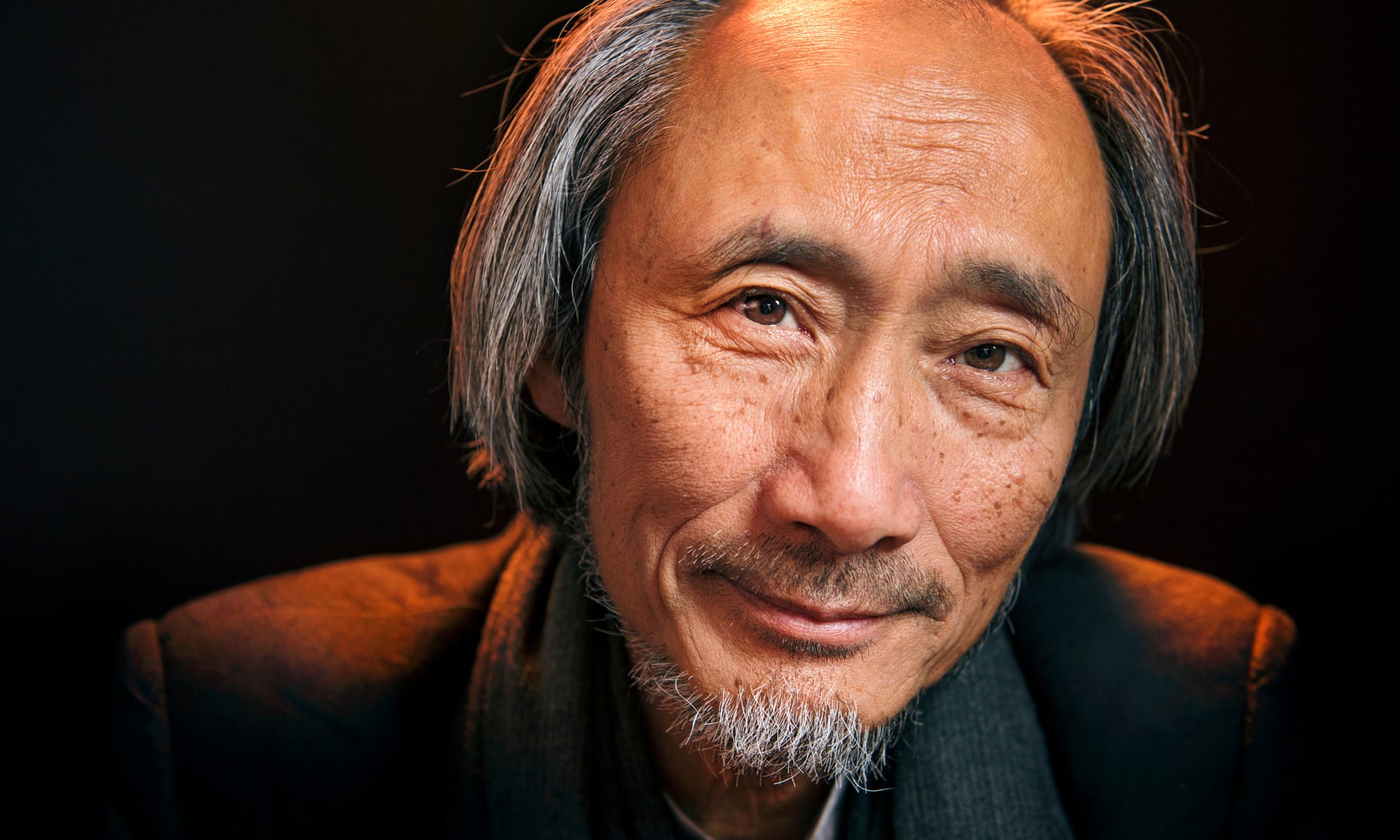

Ma Jian, writer, known as the Chinese Solzhenitsyn at the Oxford Literary Festival 2019 in Oxford, England on April 5, 2019.

Ma Jian has a flair for the provocative.

In 2012, the London Book Fair partnered with the all-powerful Chinese state agency responsible for regulating publications and the Internet—the General Administration for Press and Publication.

In protest, the author smeared an X across his face in red paint.

He then attempted to hand a copy of a book he had written, its cover also marked with a red X, to the head of the agency, who was attending the fair.

The book was about one of China’s most taboo topics—the 1989 massacre in Tiananmen Square.

Ma had reason to be angry: his books have been banned in his homeland for the last 30 years, and he has not been allowed to return to China for the last few years as the country’s dictator, Xi Jinping, has initiated a widespread crackdown on dissent.

The author was born in the Chinese city of Qingdao in 1953.

Ma had reason to be angry: his books have been banned in his homeland for the last 30 years, and he has not been allowed to return to China for the last few years as the country’s dictator, Xi Jinping, has initiated a widespread crackdown on dissent.

The author was born in the Chinese city of Qingdao in 1953.

He started his career on a more traditional path, at a petrochemical plant in Beijing, before deciding to become a photojournalist.

In the 1980s, he began hanging out in the Chinese capital’s underground literary and art scene and took up painting again—a childhood love that was interrupted by the Cultural Revolution.

He also started writing.

His first book, 1988’s Stick Out Your Tongue, inspired by his travels in Tibet, caught the attention of the country’s censors, and all copies were destroyed.

Since then, none of his books have been allowed to be published in China.

His latest work is, without a doubt, a political statement.

His latest work is, without a doubt, a political statement.

China Dream—a phrase borrowed directly from Xi who commonly uses it to describe a “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”—is a scathing, dystopian novel that follows a fictional Chinese provincial leader as he works to replace people’s dreams with government propaganda.

But Ma says that he refuses to stand down.

But Ma says that he refuses to stand down.

“I have never allowed myself to not write something for fear of consequences; that would be the death of literature in my mind,” Ma told TIME.

China Dream has already been released in the U.K., where he now lives with his wife and children, and it will be available in the U.S. on May 7.

Here’s what the writer-in-exile had to say about the new title and what is happening in China today.

China Dream has already been released in the U.K., where he now lives with his wife and children, and it will be available in the U.S. on May 7.

Here’s what the writer-in-exile had to say about the new title and what is happening in China today.

Tell us about your new book.

China Dream was inspired by the idea that China was shrouded in a veil of lies.

It was a strong desire to expose these lies and shine a light on them that drove me to write the book.

I wanted to reveal the darkness that lies at the core of Xi Jinping’s sunny utopia.

Did you draw on inspiration from your own life for the book?

[The book’s main character] Ma Daode’s task is not only to suppress memories of the past but also to control speech in the present.

My whole life has been affected by the [Chinese government’s] desire to clampdown on personal liberties and freedom of speech.

When I was living in China in the 1980s I was continually being detained, arrested for things I said, or paintings I created.

This has continued today where my books are still banned and I am forced to live in exile.

“China Dream” is a phrase commonly used by Xi Jinping and in Chinese propaganda. Why did you chose to call the book that?

When Xi Jinping rose to power and announced his China Dream of national resurgence, and made this the bedrock of his rule, I at once saw it as a crime.

It is criminal for a leader to impose a dream on a nation.

Dreams are an expression of the most unfettered realm of the human spirit.

What is your dream for China?

My dream for China is that it will become a country that respects freedom of speech, where independent thought prospers.

What is your dream for China?

My dream for China is that it will become a country that respects freedom of speech, where independent thought prospers.

This, of course, would be a time when a totalitarian regime no longer exists, where people are free to determine their own life paths and to dream their own dreams.

It will be a country that gives dignity to every individual life, where people feel safe in their own homes, and feel that they can express their thoughts freely that go against official ideology without fear of arrest or suppression.

How do you stay attuned to what is going in China while living outside of it?

In fact, I feel more attuned to what is going on in China living in London, more connected than I did in China when my movements were monitored, when I was forbidden to meet with sensitive people, where information was blocked by the firewall.

How do you stay attuned to what is going in China while living outside of it?

In fact, I feel more attuned to what is going on in China living in London, more connected than I did in China when my movements were monitored, when I was forbidden to meet with sensitive people, where information was blocked by the firewall.

Here I can know real-time, through the internet, what is happening.

Information that is restricted in China, I have full access to.

What do you want China’s youth, who have not been able to learn about what happened in Tiananmen, to know about the massacre?

My hope is that the young people of today will have an opportunity to re-connect with their own history that has been denied them.

What do you want China’s youth, who have not been able to learn about what happened in Tiananmen, to know about the massacre?

My hope is that the young people of today will have an opportunity to re-connect with their own history that has been denied them.

They need to learn the lessons of those crucial years, because the situation [in China] today is more dangerous than it has been in many decades.

Is the Chinese government succeeding in its efforts to enforce censorship?

At the moment, it looks like their system of censorship is succeeding in maintaining the Communist Party’s barbaric rule.

Is the Chinese government succeeding in its efforts to enforce censorship?

At the moment, it looks like their system of censorship is succeeding in maintaining the Communist Party’s barbaric rule.

The party has huge amounts of money, it has an army of censors.

What do you hope readers will learn from reading your book?

We are now in a state of turmoil, in a state of flux, where there is a loss of faith in all leaders, where truth is under threat.

What do you hope readers will learn from reading your book?

We are now in a state of turmoil, in a state of flux, where there is a loss of faith in all leaders, where truth is under threat.

I hope that this book can show that is vital that individuals never give up asking questions.

If you stop reflecting on the past, if you don’t question what is fed to you, if you don’t question the motives of the people who are leading you, we will all share a common fate, and that is that we will all be controlled by people that are more stupid and evil and than us.

Did any recent events in particular prompt you to start writing the book?

I only have to read the news from China; every day there is something that will fill me with rage.

Did any recent events in particular prompt you to start writing the book?

I only have to read the news from China; every day there is something that will fill me with rage.

But perhaps one of the sparks for writing of this particular book was attending the London Book Fair where China was the guest of honor.

Here in the country where I had sought refuge, where I thought that the freedom of expression was one of the founding values, I saw how the red carpet was rolled out for the Chinese censors-in-chief.

A talk you were scheduled to give in Hong Kong last year was suddenly cancelled (before being re-instated). The motivation was political. Will China Dream be published in Hong Kong?

Until now, all of my books have been published in Hong Kong in the Chinese language, but the spread of the Communist party’s control beyond its borders means that no Hong Kong publisher would dare to publish this book.

Originally there was one publisher who was willing to publish it in Hong Kong, we got quite far in the process—it had been edited and the cover had been approved.

A talk you were scheduled to give in Hong Kong last year was suddenly cancelled (before being re-instated). The motivation was political. Will China Dream be published in Hong Kong?

Until now, all of my books have been published in Hong Kong in the Chinese language, but the spread of the Communist party’s control beyond its borders means that no Hong Kong publisher would dare to publish this book.

Originally there was one publisher who was willing to publish it in Hong Kong, we got quite far in the process—it had been edited and the cover had been approved.

Suddenly they said they were not going to go ahead with it, and they did not give me a clear reason.

I can only assume that they received a message from above or they realized themselves that it could be too dangerous and they could face possible arrest as other publishers have in Hong Kong.