Buried dreams and past betrayals erupt into the present moment, in a feverish vision of contemporary Chinese society

By Madeleine Thien

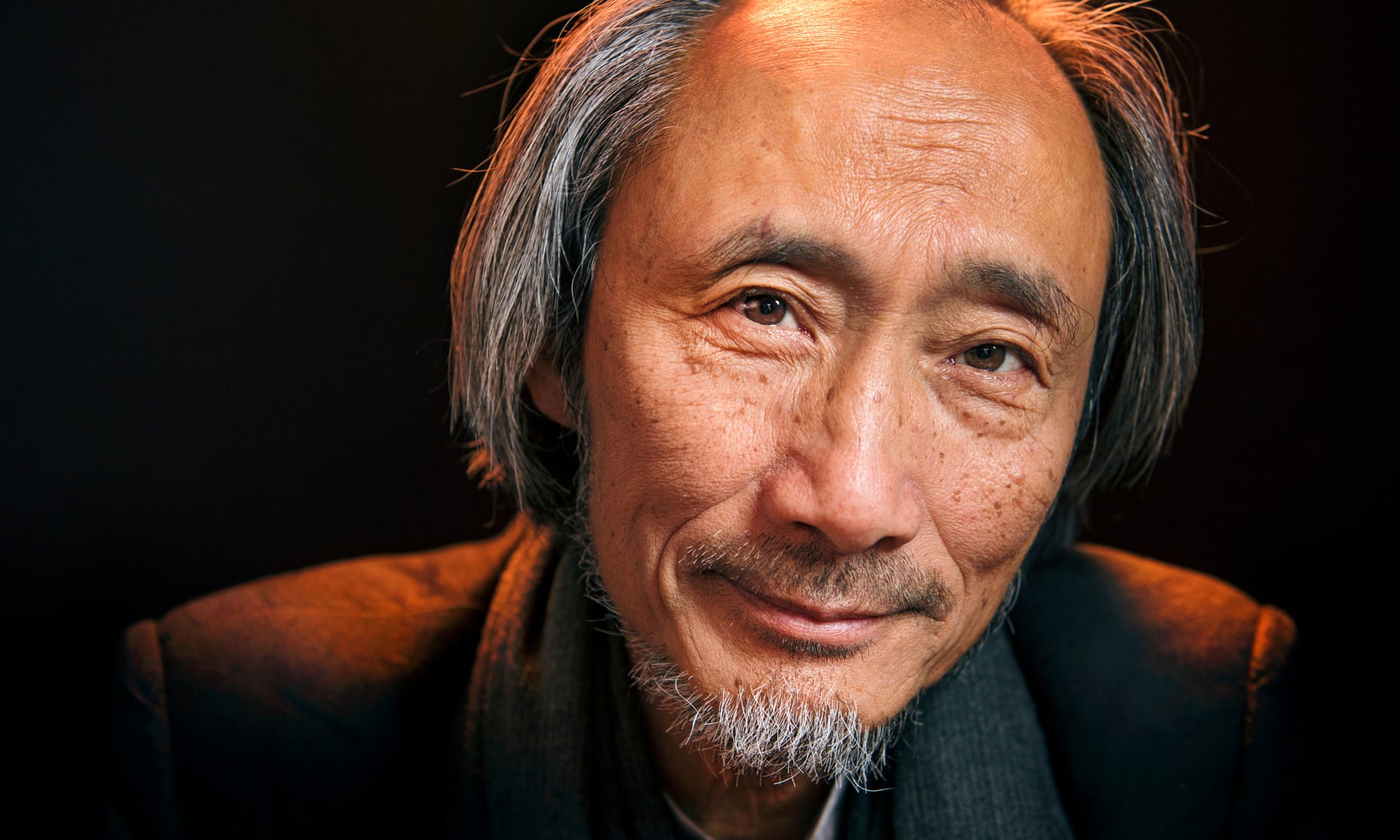

Bleakly funny … Ma Jian.

On the cover of Ma Jian’s new novel, an ancient tree is exploding in all directions, its branches seeming to lash out at the heavens.

On the cover of Ma Jian’s new novel, an ancient tree is exploding in all directions, its branches seeming to lash out at the heavens.

Designed by another exile from China, artist Ai Weiwei, the image is a haunting doorway into China Dream, a biting and humane novel of stunning concision in which buried dreams and past betrayals erupt into the present moment.

In 2012, Xi Jinping used the phrase the Chinese Dream (zhōngguó mèng) to describe “the great rejuvenation” of the nation.

In 2012, Xi Jinping used the phrase the Chinese Dream (zhōngguó mèng) to describe “the great rejuvenation” of the nation.

A national solidarity movement, the Chinese Dream attempts to fuse cultural pride and individual self-realisation with the country’s economic growth and rising influence.

The slogan is everywhere, on billboards, in speeches and advertisements, and mixes patriotism and self-help with the “twin goals of reclaiming national pride and achieving personal wellbeing”.

Ma was born in 1953, the same year as Xi Jinping.

Ma was born in 1953, the same year as Xi Jinping.

Both men witnessed the shaming, exile and loss of family members during Mao Zedong’s political campaigns.

In 1983, Ma himself was arrested for the crime of spiritual pollution; he chronicled his exile to the most remote regions of the country in Red Dust, an unforgettable memoir of post-Mao China.

Today, the lives of Ma and Xi remain strikingly at odds.

In 2018, Xi ended term limits on the presidency, thus opening the door to his indefinite rule.

Ma, barred from even entering China, has mischievously stolen Xi’s signature slogan.

China Dream’s antihero, Ma Daode, is vice-chair of the local writers’ association and director of the newly created China Dream Bureau, dedicated to ensuring that the Chinese Dream enters “the brain of every resident of Ziyang City”.

China Dream’s antihero, Ma Daode, is vice-chair of the local writers’ association and director of the newly created China Dream Bureau, dedicated to ensuring that the Chinese Dream enters “the brain of every resident of Ziyang City”.

Ma Daode is clever and influential: he has stashed mooncakes filled with little gold bars in his attic, and is juggling so many lovers that he keeps a “Fragrant Beauties Register”; one lover calls him Mr Dirty Dream.

But his hard-won success is being undermined by terrifying slivers of memory.

He places his hopes in an imagined “China Dream Device” which, if implanted, would make all dreams – first and foremost his own – comply with Xi’s vision and allow him to wake up inside “a life of unbridled joy”.

Bleakly funny, incisive, stinging and – in its most destabilising passages – gut-wrenching, China Dream, brilliantly translated by Flora Drew, is set at a time when reality and dystopia have begun to bleed into one another.

Bleakly funny, incisive, stinging and – in its most destabilising passages – gut-wrenching, China Dream, brilliantly translated by Flora Drew, is set at a time when reality and dystopia have begun to bleed into one another.

In the kaleidoscope of Ma Daode’s thoughts, different times converge; dream locations are overlaid on the sites of nightmares.

A wild grove outside Ziyang City is, in the present, a demolition site making ready for the very expensive Yaobang Industrial Park; in the 1990s, a secret cemetery; in 1968, the mass grave for hundreds of Red Guards killed during internecine warfare.

It is also the deserted place where Ma Daode buried his parents, who killed themselves in 1966, during the first year of the Cultural Revolution, after being mercilessly beaten by Red Guards.

In the novel, all times come to us in the present tense.

Ai Weiwei’s ancient tree on the cover is, it appears, detonating its branches into the now.

Even an orgy can’t help the beleaguered Ma Daode stay in the moment.

Even an orgy can’t help the beleaguered Ma Daode stay in the moment.

In a comic passage that grows increasingly surreal and moving, he entertains three women in a room decorated to resemble Chairman Mao’s private railway car.

As Cultural Revolution songs, popular once more, ring out from the karaoke machine, Ma Daode recites Song dynasty poetry.

On a TV screen, the 2013 sentencing of Bo Xilai for corruption and abuse of power plays out on the evening news.

One of the women laughs when Ma Daode complains that her Red Guard costume is inauthentic, replying: “Our boss told us we are all the heirs of Communism.”

His body, heart and mind are divided into so many eras and conflicting desires, it’s no wonder he believes that the cure is China Dream Soup, a broth of eternal forgetting he will obtain from a qigong healer and market to the world.

“But what I want to forget the most,” he says, “is my shameful betrayal of my father. When I see him again, I will fall to my knees and beg for his forgiveness.”

But how can Ma Daode erase his remorse at responsibility for his parents’ deaths without also consigning every memory of them to oblivion?

Xi Jinping promotes ‘the dream’ on a billboard in China’s northern Hebei province.

Over the 40 years of his career, Ma has ingeniously chronicled a China struggling both to change and to remember.

Beijing Coma, his unparalleled novel of the 1989 Tiananmen demonstrations, is a classic work, as is The Dark Road, the macabre, spellbinding story of a mother’s determined journey to outwit the one-child policy.

By rights, Ma should be recognised as one of China’s greatest living novelists, yet his name cannot be mentioned in the national press.

Beijing’s censorship of his books – banned for the last 30 years – has been effective.

Recently, a well read and accomplished Shanghai editor told me, after I mentioned Ma, that she had never heard of him.

“What kind of books does he write?” she asked, perplexed.

“Does he write in Chinese?”

In the last chapters of China Dream, Ma Daode, remembering his own life and the lives of his parents, tries to renounce his need to mourn.

In the last chapters of China Dream, Ma Daode, remembering his own life and the lives of his parents, tries to renounce his need to mourn.

He could be speaking to us, or to China’s contemporary writers and historians, or to the future, when he says: “Those who have tears, lend them to those who have none.”

Last year, an essay by Chinese blogger Zhang Wumao, which described Beijing as a city where people “cannot move, cannot breathe”, and where migrant workers “strive for over a decade to buy an apartment the size of a bird cage”, went viral.

It was swiftly censored and erased from the internet, and Chinese state media reprimanded Zhang, insisting that Beijingers “are all the more real because of their dreams”.

The fictional Ma Daode, too, wishes to be remade by fantasies.

He goes to great lengths to step out of history, to be reborn and absolved by a beautiful dream.

Ma has a marksman’s eye for the contradictions of his country and his generation, and the responsibilities and buried dreams they carry.

Ma has a marksman’s eye for the contradictions of his country and his generation, and the responsibilities and buried dreams they carry.

His perceptiveness, combined with a genius for capturing people who come from all classes, occupations, backgrounds and beliefs; for identifying the fallibility, comedy and despair of living in absurd times, has allowed him to compassionately detail China’s complex inner lives.

Censoring his novels and banning his name have been Beijing’s cynical response to Ma’s artistry, and to the human lives that the novelist cannot forget, even as the Chinese Dream envelops them.

• China Dream by Ma Jian, translated by Flora Drew (Chatto, £12.99).

• China Dream by Ma Jian, translated by Flora Drew (Chatto, £12.99).

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire