Emma Graham-Harrison

Flowers and a photo of the whistleblower doctor Li Wenliang at a hospital in Wuhan.

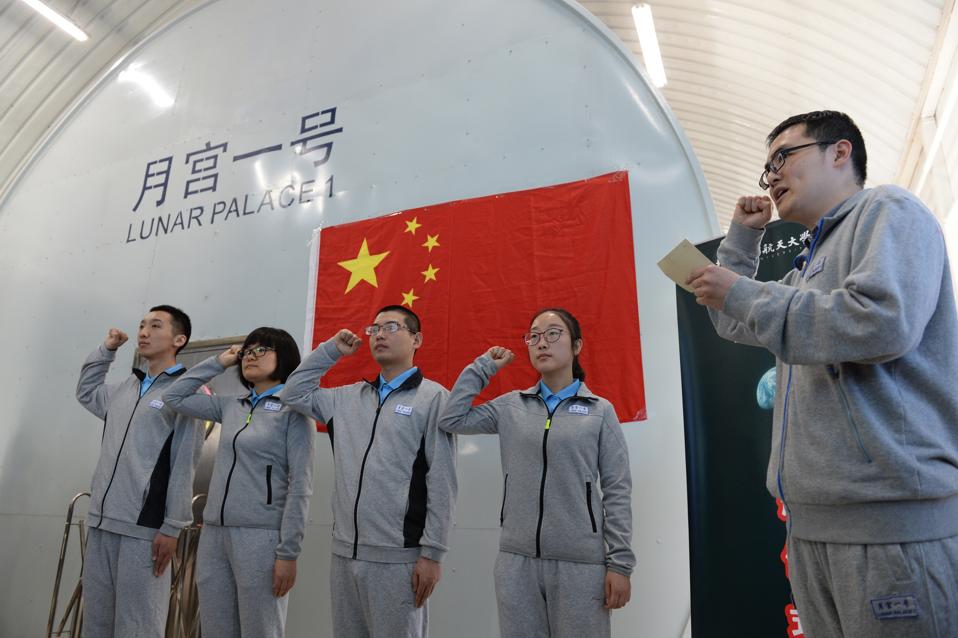

China’s two new hospitals built in as many weeks were the official face of its fight against the Chinese coronavirus in Wuhan.

As the city was locked down, authorities promised that thousands of doctors would be on hand to treat 2,600 patients on the facilities’ wards.

Timelapse videos tracked the fast construction of the hospitals, and state media celebrated their opening in early February.

Timelapse videos tracked the fast construction of the hospitals, and state media celebrated their opening in early February.

The only thing missing a week later? Patients.

Four days after its opening, the larger Leishenshan hospital had only 90 patients, on wards designed for 1,600, but was reporting no spare beds, Wuhan city health data, first reported by the Chinese magazine Caixin, showed.

The other facility, Huoshenshan, had not yet filled its 1,000 beds a week after opening.

Meanwhile, the city was setting up emergency hospitals in exhibition halls and a sports stadium, and medics were still turning ill people away.

Meanwhile, the city was setting up emergency hospitals in exhibition halls and a sports stadium, and medics were still turning ill people away.

China has the world’s largest army but it has not deployed any field hospitals to Wuhan.

The gulf between the vision of vast new hospitals created and thrown into action within days and the more complicated reality on the ground is a reminder of one of the main challenges for Beijing as it struggles to contain the Chinese coronavirus: its own secretive, authoritarian system of government and its vast censorship and propaganda apparatus.

Communist party apparatus well honed to crush dissent also muffles legitimate warnings.

The gulf between the vision of vast new hospitals created and thrown into action within days and the more complicated reality on the ground is a reminder of one of the main challenges for Beijing as it struggles to contain the Chinese coronavirus: its own secretive, authoritarian system of government and its vast censorship and propaganda apparatus.

Communist party apparatus well honed to crush dissent also muffles legitimate warnings.

A propaganda system designed to support the party and state cannot be relied on for accurate information.

That is a problem not just for families left bereft by the Chinese coronavirus and businesses destroyed by the sudden shutdown, but for a world trying to assess Beijing’s success in controlling and containing the disease.

“China’s centralised system and lack of freedom of press definitely delay a necessary aggressive early response when it was still possible to contain epidemics at the local level,” said Ho-fung Hung, a professor in political economy at Johns Hopkins University in the US.

Beijing did go public about the Chinese virus faster than during the 2002-3 Sars crisis.

“China’s centralised system and lack of freedom of press definitely delay a necessary aggressive early response when it was still possible to contain epidemics at the local level,” said Ho-fung Hung, a professor in political economy at Johns Hopkins University in the US.

Beijing did go public about the Chinese virus faster than during the 2002-3 Sars crisis.

But it has become increasingly clear that the local government was engaged in a concerted attempt to cover up the crisis during the early weeks of the outbreak, which allowed it to fester at a time when it would have been much easier to contain.

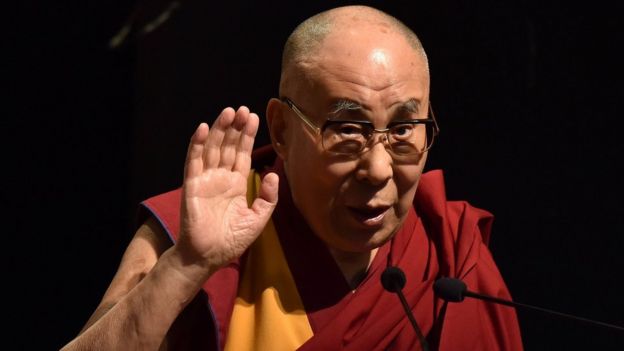

Two officials have been fired, Wuhan’s mayor admitted failings in a live interview on national television, and the central government has sent a team to investigate the treatment of the whistleblowing doctor Li Wenliang.

Security forces punished Li, 34, for trying to warn colleagues about the risks of a dangerous new disease at the end of December.

Security forces punished Li, 34, for trying to warn colleagues about the risks of a dangerous new disease at the end of December.

Just over a month later he became one of the youngest victims of the Chinese coronavirus.

His death made him a household name and triggered a rare discussion in China about freedom of speech.

In a biting essay that laid the blame for the crisis with Xi Jinping, a dissident intellectual claimed China’s centralisation and culture of silence had played a key role in the spread of the disease.

“It began with the imposition of stern bans on the reporting of factual information that served to embolden deception at every level of government,” Xu Zhangrun wrote in his essay Viral Alarm, When Fury Overcomes Fear, according to a translation by Geremie Barmé on the website ChinaFile.

“It only struck its true stride when bureaucrats throughout the system shrugged off responsibility for the unfolding situation while continuing to seek the approbation of their superiors,” Xu continued.

In a biting essay that laid the blame for the crisis with Xi Jinping, a dissident intellectual claimed China’s centralisation and culture of silence had played a key role in the spread of the disease.

“It began with the imposition of stern bans on the reporting of factual information that served to embolden deception at every level of government,” Xu Zhangrun wrote in his essay Viral Alarm, When Fury Overcomes Fear, according to a translation by Geremie Barmé on the website ChinaFile.

“It only struck its true stride when bureaucrats throughout the system shrugged off responsibility for the unfolding situation while continuing to seek the approbation of their superiors,” Xu continued.

“They all blithely stood by as the crucial window of opportunity to deal with the outbreak of the infection snapped shut in their faces.”

A Chinese coronavirus patient is discharged from a field module hospital after recovery in Wuhan.

Without a free press, elections or much space for civil society, there are few ways for citizens to hold their rulers accountable.

Instead, local officials answer only to a party hierarchy that puts a premium on stability and economic growth.

Prof Steve Tsang, director of the Soas China Institute, said: “China is not a poor country. But the incentives are not for a health director (for example) to respond to public health crises in Wuhan first and foremost. The incentive is to do what the party wants … and not embarrass the party.”

Prof Steve Tsang, director of the Soas China Institute, said: “China is not a poor country. But the incentives are not for a health director (for example) to respond to public health crises in Wuhan first and foremost. The incentive is to do what the party wants … and not embarrass the party.”

The cost of trying to curb the Chinese coronavirus when it first emerged – high-profile moves to close the market where it originated, cull and destroy livestock, quarantine and compensate victims, cancel mass festivities for the new year – would have seemed a risky gamble for little reward.

“That might have ended it, or not,” Tsang said.

“That might have ended it, or not,” Tsang said.

“[But] since you stopped the virus from developing, you have nothing to show. You quashed a potential threat that may not have existed.”

Even when the government reversed course and announced a crisis, it appeared to be focused more on propaganda than on managing the disease, he said.

Even when the government reversed course and announced a crisis, it appeared to be focused more on propaganda than on managing the disease, he said.

It could have deployed medics and a field hospital to Wuhan almost overnight rather than building new hospitals.

It is unclear why they chose not to do so.

It is unclear why they chose not to do so.

But a country setting up field hospitals looks like one in crisis.

A government expanding hospitals looks like one in control.

“Ten days is a very long time when you are looking at a public health crisis like that,” Tsang said.

“But a new hospital built from the ground up, that’s a world record.”

Diggers begin constructing a new 1,000-bed hospital in Wuhan.

Questions about China’s transparency still hang over efforts to manage the disease.

Scientists are concerned about its spread in areas that have become new hubs of the disease.

Zhejiang and Guangdong province – both industrial centres – have reported more than 1,000 cases, as has inland Henan province.

That is higher than the number of cases reported in Hubei province when the lockdown of Wuhan was announced in January.

That is higher than the number of cases reported in Hubei province when the lockdown of Wuhan was announced in January.

But with the economy badly strained by the long shutdown, Chinese authorities are urging people to start heading back to work in “orderly” fashion in these areas.

There have also been doubts about the accuracy of the tally of cases, after many families reported struggling to get testing for sick relatives.The test numbers may be accurate, and disease control measures in place elsewhere may be sufficient to control a virus that scientists already understand much better than they did a few weeks ago.

There have also been doubts about the accuracy of the tally of cases, after many families reported struggling to get testing for sick relatives.The test numbers may be accurate, and disease control measures in place elsewhere may be sufficient to control a virus that scientists already understand much better than they did a few weeks ago.

But if China cannot address the systemic failings that allowed the outbreak to fester originally, it may struggle to control this epidemic, avert the next one and secure the global trust and cooperation needed to fight disease.

“There is no one quick fix to the Chinese system to make it respond better next time,” said Hung. “But if there is one single factor that could increase the government’s responsiveness to this kind of crisis, [it would be] a free press.”

“There is no one quick fix to the Chinese system to make it respond better next time,” said Hung. “But if there is one single factor that could increase the government’s responsiveness to this kind of crisis, [it would be] a free press.”

The recently closed People Book Cafe in Hong Kong’s Causeway Bay district, which sold books banned by the Communist Party of China.

The recently closed People Book Cafe in Hong Kong’s Causeway Bay district, which sold books banned by the Communist Party of China.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/60688179/acastro_180508_1777_google_IO_0001.0.jpg)