By Wade Shepard

Sri Lanka's most corrupted President Mahinda Rajapaksa Mahinda Rajapaksa, the Chinese Ambassador to Sri Lanka Cheng Xueyuan and attendees look at a proposed construction model of Port City during an event to officially declare the 269 hectares of land reclaimed from the sea for the project as part of the capital Colombo on December 7, 2019.

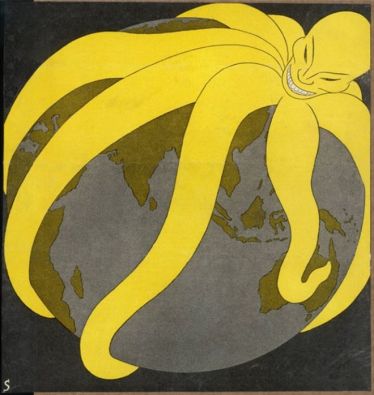

China’s Belt and Road initiative (BRI), a network of enhanced overland and maritime trade routes better linking China with Asia, Europe and Africa began in 2013 with much fanfare and hope. Upwards of a trillion dollars were being put on the table to boost economic development in globalization’s final frontiers, Asia and Africa’s infrastructure gap was to be lessened, and the world’s second largest economy was taking more of an active role in international affairs with the prospect of creating a true multi-polar global power structure.

With catchphrases like “a rising tide lifts all ships,” China stepped beyond its borders to an extent that hasn’t been seen for centuries—perhaps ever—and was welcomed by many emerging markets with open arms.

But today, nearly seven years since the Belt and Road began, the story is much different, as Chinese investment has become a euphemism for wasteful spending, environmental destruction and untenable debt.

But today, nearly seven years since the Belt and Road began, the story is much different, as Chinese investment has become a euphemism for wasteful spending, environmental destruction and untenable debt.

Many major projects are currently strewn around the world in half-finished disrepair and the opportunities that were sold to local populations rarely materialized.

All up and down the Belt and Road, projects have been marred by delays, financial implosions and violent outpourings of negative public sentiment.

In the initial stages of the Belt and Road, it seemed as if China was trying to rewrite the book on international development.

In the initial stages of the Belt and Road, it seemed as if China was trying to rewrite the book on international development.

The projects were bigger, more costly, and riskier than what the world was used to seeing, which created a buzz and sense of excitement: could China step up onto the global stage and show us how it’s done?

While the news tickers sparkled with headlines of multi-billion dollar deals, big moves, and action along the Belt and Road, a broader view would have shown that a large portion of these deals were being made with countries that had credit ratings classified as “junk.”

Making big deals with countries like Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Malaysia showed the initial propensity of the Belt and Road to shoot for quantity over quality, expediency over transparency—and the reactions from this strategy was quickly felt across the entire network.

It was in Sri Lanka that the deficiencies of China’s international development activities were first revealed globally.

It was in Sri Lanka that the deficiencies of China’s international development activities were first revealed globally.

China partnered with Sri Lanka’s most corrupted president, Mahinda Rajapaksa, who now faces allegations of financial irregularities, to build a series of infrastructure mega-projects in Hambantota, a vastly undeveloped region on the island nation’s southern coast.

To start, the plan called for a new deep sea port, an airport, a stadium, a giant conference center and many miles of new roadways.

These projects were mostly funded with loans from China, which a few years later Sri Lanka struggled to pay back, as the country sunk into a debt trap of its own making.

China eventually seized a 70% share of the deep sea port at Hambantota for 99 years for $1.12 billion.

China eventually seized a 70% share of the deep sea port at Hambantota for 99 years for $1.12 billion.

While this at first appeared to be a debt-for-equity swap, news later came out that Sri Lanka actually used the money to beef up its foreign reserves and make some other foreign debt repayments to save itself from economic collapse.

However, the optics on the situation were entirely unhelpful, with headlines like “How China Got Sri Lanka to Cough Up a Port” echoed across media sources around the world as the “Chinese debt trap diplomacy” theory was born.

The Hambantota fiasco put a black mark on the Belt and Road’s financing strategies and served as a warning for emerging markets looking to make similar deals with China.

The Hambantota fiasco put a black mark on the Belt and Road’s financing strategies and served as a warning for emerging markets looking to make similar deals with China.

Bangladesh, Malaysia, Myanmar, Pakistan and Sierra Leone have all subsequently decided to cancel or downsize some of their Belt and Road projects over concerns of ending up like Sri Lanka.

China’s bags of money, which emerging markets were ogling over in the early days of the Belt and Road, seem to have lost a touch of their luster.

Chinese dictator Xi Jinping speaks with Sri Lanka's most corrupted President Mahinda Rajapaksa.

Chinese dictator Xi Jinping speaks with Sri Lanka's most corrupted President Mahinda Rajapaksa.

“As Chinese companies push deeper into emerging markets, inadequate enforcement and poor business practices are turning the BRI into a global trail of trouble,” wrote Jonathan Hillman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

“A long list of Chinese companies have been debarred from the World Bank and other multilateral development banks for fraud and corruption, which covers everything from inflating costs to giving bribes.”

When the Belt and Road was first announced, Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak welcomed the initiative, and China quickly became the top source of FDI in Malaysia.

When the Belt and Road was first announced, Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak welcomed the initiative, and China quickly became the top source of FDI in Malaysia.

According to the World Bank, between 2010 and 2016 nearly $36 billion was pumped into Malaysia by Chinese state-owned firms.

Multiple big ticket infrastructure projects—including the East Coast Rail Link project and a massive port city called Melaka Gateway—were started, Chinese firms bought up multiple Malaysian ports, and bonafide mega-projects, such as the $100 billion, 250,000+ person Forest City, were being built with Chinese direction and financial backing.

Then came the problems.

Then came the problems.

News of the 1MDB and other scandals connected with the prime minister came out, as it was discovered that over $7.5 billion of government money had disappeared.

Via Belt and Road projects, China had a role in trying to help the embattled prime minister cover evidence of financial irregularities by artificially inflating the costs of infrastructure projects so the excess could be available for other uses.

This favor came with a catch, however, as Malaysia was to give Chinese companies big stakes in national railway and pipeline projects and permission for the Chinese navy to use two Malaysian ports.

This deal didn’t come to pass, but it yet again cast the Belt and Road in a dubious light.

There are many other examples of parties from China allegations of corruption up and down the Belt and Road.

There are many other examples of parties from China allegations of corruption up and down the Belt and Road.

Bangladesh shut down a highway project that was supposed to have been built by the China Harbour Engineering Company due to the company reputedly offering a Bangladeshi official a bribe, Chinese development funds were reportedly allocated for Rajapaksa’s ill-fated reelection campaign, Chinese tech giants Huawei and ZTE have been probed for wrongdoing in numerous BRI countries, and the U.S. arrested the emissary of China’s CEFC Energy Company for illicit payments to officials in Chad and Uganda.

A 2017 McKinsey survey found that between 60% to 80% of Chinese companies in Africa admitted to paying bribes and, almost needless to say, in the latest Transparency International Bribe Payers Index, Chinese firms scored second to last.At this point, it is clear that the BRI does not keep good company.

In addition to most Belt and Road countries having poor debt ratings, they also tend not to fare so well in international corruption indexes.

According to the TRACE Bribery Risk Matrix, 10 Belt and Road countries were deemed to be among the countries most at risk to bribery.

While the lack of transparency and oversight as to what China is doing abroad was a boon in the early days of the Belt and Road, the initiative has lost support amid the scandals, debt traps and failed projects that have emerged in recent years.

While the lack of transparency and oversight as to what China is doing abroad was a boon in the early days of the Belt and Road, the initiative has lost support amid the scandals, debt traps and failed projects that have emerged in recent years.

Countries along the corridors are now operating with far more caution and scrutiny, pumping the breaks on many projects and potentially setting the BRI back for years to come.

In this photo taken Friday, March 1, 2019, a woman walks by Chinese flag placed on a street in Belgrade, Serbia.

In this photo taken Friday, March 1, 2019, a woman walks by Chinese flag placed on a street in Belgrade, Serbia. French President Emmanuel Macron, Xi Jinping and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker hold a news conference with German Chancellor Angela Merkel at the Elysee presidential palace in Paris, France, March 26, 2019.

French President Emmanuel Macron, Xi Jinping and European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker hold a news conference with German Chancellor Angela Merkel at the Elysee presidential palace in Paris, France, March 26, 2019. Power grid stand against the residential and office buildings in Beijing as the capital of China is shrouded by mild pollution haze on June 5, 2017.

Power grid stand against the residential and office buildings in Beijing as the capital of China is shrouded by mild pollution haze on June 5, 2017.

Murghab, established as an army outpost in the 1890s by Russian Cossacks, is about 85 miles north of the remote Chinese border outpost.

Murghab, established as an army outpost in the 1890s by Russian Cossacks, is about 85 miles north of the remote Chinese border outpost.