China's Leading Actress Fan Bingbing Has Vanished.

By ELI MEIXLER / HONG KONG

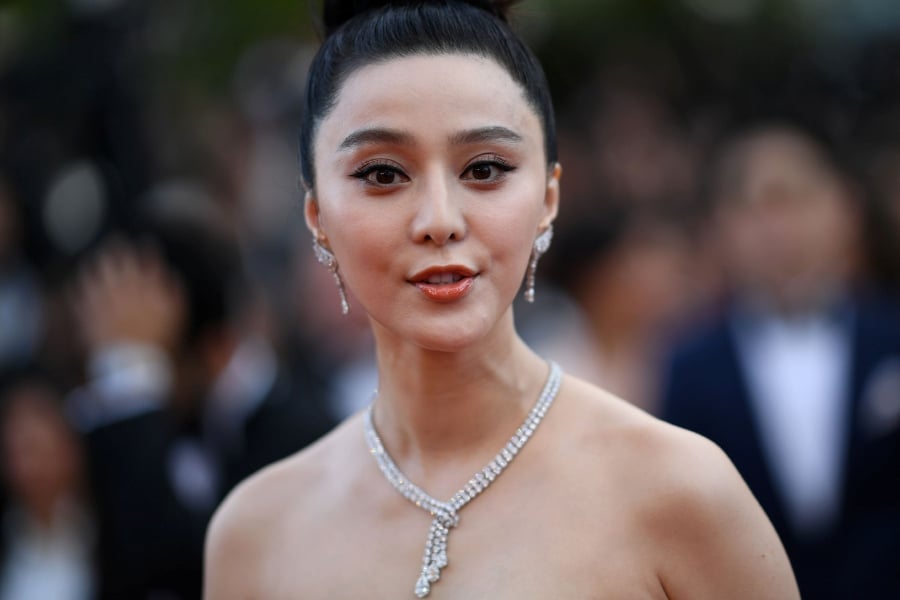

In past years, actress Fan Bingbing was a regular presence on film festival red carpets and fashion catwalks from Barcelona to Busan.

And then, suddenly, she wasn’t.

Film fans are expressing alarm at Fan’s disquieting recent disappearance from public life: she was last seen on July 1, while visiting a children’s hospital.

Film fans are expressing alarm at Fan’s disquieting recent disappearance from public life: she was last seen on July 1, while visiting a children’s hospital.

Her account on China’s popular Sina Weibo social media network, where she has 63 million followers, has been silent since July 23.

Speculation is linking the disappearance of Fan, one of cinema’s top-earners, to an alleged tax evasion scandal at a time when China’s state-controlled film industry is cutting back on bloated budgets and star-driven blockbusters.

If so, it would be a swift reversal for the celluloid superstar, whose rapid ascent as an actress and fashion icon seemed eclipsed only by her potential.

Speculation is linking the disappearance of Fan, one of cinema’s top-earners, to an alleged tax evasion scandal at a time when China’s state-controlled film industry is cutting back on bloated budgets and star-driven blockbusters.

If so, it would be a swift reversal for the celluloid superstar, whose rapid ascent as an actress and fashion icon seemed eclipsed only by her potential.

A Chinese state news report assured readers last week that matters surrounding the actress—who featured in 2017’s TIME 100—were “under control.”

But like its subject, the report quickly disappeared.

Here’s what we know:

A rising star

Not long ago, Fan, 36, seemed poised to become one of the biggest crossover stars in the world: a China-born, English-speaking workaholic armed with a formidable combination of acting, singing, and modeling skills.

Fan became a Chinese household name in 1999 with the TV series My Fair Princess, but broke into stardom in 2003’s Cell Phone, the year’s highest-grossing Chinese film, for which she won Best Actress honors at the Hundred Flowers Awards, China’s equivalent of the Golden Globes.

Fan won again in 2008, and began to pick up leading roles and international festival awards from Taiwan, Tokyo, and San Sebastián.

Here’s what we know:

A rising star

Not long ago, Fan, 36, seemed poised to become one of the biggest crossover stars in the world: a China-born, English-speaking workaholic armed with a formidable combination of acting, singing, and modeling skills.

Fan became a Chinese household name in 1999 with the TV series My Fair Princess, but broke into stardom in 2003’s Cell Phone, the year’s highest-grossing Chinese film, for which she won Best Actress honors at the Hundred Flowers Awards, China’s equivalent of the Golden Globes.

Fan won again in 2008, and began to pick up leading roles and international festival awards from Taiwan, Tokyo, and San Sebastián.

In 2016, she earned $17 million, according to Forbes, making her the world’s fifth-highest paid actress.

The following year, she sat on the Cannes Film Festival Official Competition Jury, where she promised to assess films “from an Asian perspective.”

She also logged side roles American films like X-Men: Days of Future Past and Ironman 3 after, as she told TIME last year, “[Hollywood] wanted to add Asian faces and found me.”

She also logged side roles American films like X-Men: Days of Future Past and Ironman 3 after, as she told TIME last year, “[Hollywood] wanted to add Asian faces and found me.”

It was effective: her brief role as “Blink” helped propel X-Men to a $39.35 million opening weekend in China.

Earlier this year, she was cast in 355, an espionage thriller, among a multinational ensemble that included Jessica Chastain, Penélope Cruz, Lupita Nyong’o, and Marion Cotillard.

Earlier this year, she was cast in 355, an espionage thriller, among a multinational ensemble that included Jessica Chastain, Penélope Cruz, Lupita Nyong’o, and Marion Cotillard.

Her place in the pantheon of leading actors seemed secure.

“In 10 years’ time…I’m sure I will be the heroine of X-Men,” she predicted to TIME last February.

A hint of scandal

But her once certain ascension was jeopardized in May, when CCTV presenter Cui Yongyuan leaked a pair of contracts that allegedly showed Fan double-billing an unidentified production, first for 10 million renminbi ($1.6 million), and then for 50 million renminbi ($7.8 million) for the same work.

The documents appeared to reveal an arrangement, known as “yin-yang” contracts, wherein one contract reflects an actor’s actual earnings while a second, lower figure is submitted to tax authorities, the BBC reported.

A hint of scandal

But her once certain ascension was jeopardized in May, when CCTV presenter Cui Yongyuan leaked a pair of contracts that allegedly showed Fan double-billing an unidentified production, first for 10 million renminbi ($1.6 million), and then for 50 million renminbi ($7.8 million) for the same work.

The documents appeared to reveal an arrangement, known as “yin-yang” contracts, wherein one contract reflects an actor’s actual earnings while a second, lower figure is submitted to tax authorities, the BBC reported.

According to the South China Morning Post, Cui then called for the Chinese authorities to “step up regulations on show business.”

In June, the Jiangsu Province State Administration of Taxation opened a tax evasion investigation focusing on the entertainment industry.

In June, the Jiangsu Province State Administration of Taxation opened a tax evasion investigation focusing on the entertainment industry.

Fan’s film studio, which denied the allegations, is based in Jiangsu, according to the Post.

The lack of an official statement on her whereabouts has spurred tabloid speculation that Fan was banned from acting or placed under house arrest.

The lack of an official statement on her whereabouts has spurred tabloid speculation that Fan was banned from acting or placed under house arrest.

Last week, according to the Guardian, a report in China’s state-run Securities Journal claimed that Fan would “accept legal judgement,” though the article did not specify her offense, and was removed shortly after publication.

The whiff of impropriety has already impacted her cachet: Australian vitamin brand Swisse suspended use of Fan’s image in advertisements, while her name was removed from promotional materials for the upcoming Unbreakable Spirit, starring Bruce Willis.

Adding insult to financial and professional injury, the BBC reports that Fan has been rated last in a ranking of Chinese celebrities’ personal integrity and charitable work, scoring zero out of 100 in the 2017-2018 China Film and Television Star Social Responsibility Report published Tuesday by a Chinese university.

The whiff of impropriety has already impacted her cachet: Australian vitamin brand Swisse suspended use of Fan’s image in advertisements, while her name was removed from promotional materials for the upcoming Unbreakable Spirit, starring Bruce Willis.

Adding insult to financial and professional injury, the BBC reports that Fan has been rated last in a ranking of Chinese celebrities’ personal integrity and charitable work, scoring zero out of 100 in the 2017-2018 China Film and Television Star Social Responsibility Report published Tuesday by a Chinese university.

That’s despite the fact that Fan co-founded a charity to provide surgery for children with congenital heart disease in rural Tibet, which she called her “greatest achievement” in a 2003 interview with the Financial Times.

In 2015, she also donated a million renminbi ($146,000) to relatives of firemen killed in the Tianjin chemical warehouse disaster; the following year a different index listed Fan among the 10 most philanthropic Chinese celebrities.

A cautionary tale

Other, more salacious theories have claimed to account for Fan’s fall from grace.

Last year, she filed a defamation lawsuit against exiled Chinese billionaire Guo Wengui, who alleged sexual affairs between celebrities, including Fan, and top Chinese Communist Party officials.

A cautionary tale

Other, more salacious theories have claimed to account for Fan’s fall from grace.

Last year, she filed a defamation lawsuit against exiled Chinese billionaire Guo Wengui, who alleged sexual affairs between celebrities, including Fan, and top Chinese Communist Party officials.

And when the yin-yang contracts came to light, Fan was shooting a sequel to Cell Phone that Cui, her CCTV accuser, complained bore an uncomfortable resemblance to his own life, the Post reports.

Actor Jackie Chan has meanwhile dispelled rumors that he recommended Fan seek asylum in the U.S.

She may also be the victim of industry belt-tightening, following a series of costly flops.

Actor Jackie Chan has meanwhile dispelled rumors that he recommended Fan seek asylum in the U.S.

She may also be the victim of industry belt-tightening, following a series of costly flops.

Last year, the $150 million, Matt Damon-led The Great Wall, China’s most expensive film ever, recouped just $18.4 million in its North American opening.

In July, the blockbuster Asura was promptly pulled from Chinese box offices after generating just $7.4 million.

In June, the government instituted new salary ceilings on film and TV actors, blaming “sky-high” salaries and yin-yang contracts for creating a “distorted” culture of “money worship,” according to the BBC.

Fan’s plight also underscores fundamental divisions between Hollywood and the Chinese film industry, where state censors still exert considerable control over content and celebrate stars who advocate fealty to the Communist Party.

But Fan’s supporters have remain loyal, yearning for news or sight of the absent actress.

Fan’s plight also underscores fundamental divisions between Hollywood and the Chinese film industry, where state censors still exert considerable control over content and celebrate stars who advocate fealty to the Communist Party.

But Fan’s supporters have remain loyal, yearning for news or sight of the absent actress.

“I have a hunch that you will be back, right?,” one posted on Weibo.

“We’ll wait for you”