By Tom Phillips in Beijing

Earlier this week Chinese authorities claimed Gui had been released on 17 October although his daughter disputed that claim.

A Swedish bookseller who spent more than two years in custody after his abduction by Chinese agents is now “half free”, a friend has claimed, amid suspicions he is still being held under guard by security officials in eastern China.

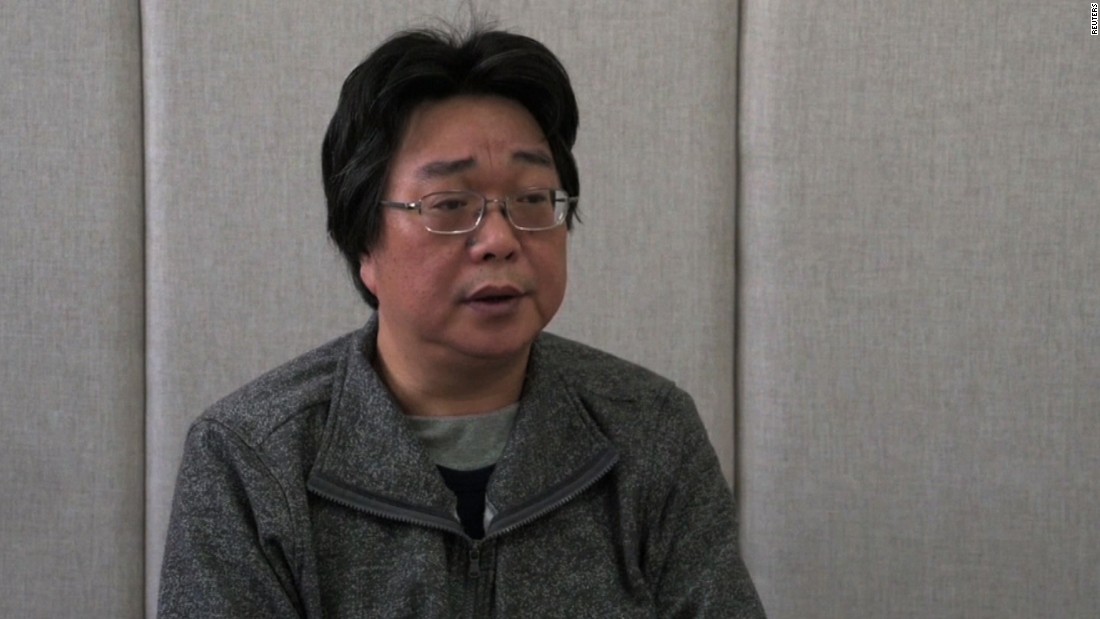

Gui Minhai, a Hong Kong-based publisher who specialised in books about China’s political elite, mysteriously vanished from his Thai holiday home in October 2015.

He later reappeared in mainland China where he was imprisoned on charges relating to a deadly drunk-driving incident more than a decade earlier.

Gui’s disappearance – and that of four other booksellers, including one British citizen – was seen as part of a wider crackdown on Communist party opponents that has gripped China since Xi Jinping took power in 2012.

Details of Gui’s two-year detention have remained murky but he is understood to have been held for at least part of that time in the eastern port city of Ningbo.

Gui’s disappearance – and that of four other booksellers, including one British citizen – was seen as part of a wider crackdown on Communist party opponents that has gripped China since Xi Jinping took power in 2012.

Details of Gui’s two-year detention have remained murky but he is understood to have been held for at least part of that time in the eastern port city of Ningbo.

Earlier this week Chinese authorities claimed he had been released on 17 October, although Gui’s daughter, Angela, disputed that claim on Tuesday, telling the Guardian he had yet to contact her and appeared still to be in “some sort of custody”.

On Friday, after several days of uncertainty about Gui’s whereabouts, reports emerged that appeared to confirm his partial release.

Bei Ling, a Boston-based dissident writer and friend, said Gui was in Ningbo and living in rented accomodation.

On Friday, after several days of uncertainty about Gui’s whereabouts, reports emerged that appeared to confirm his partial release.

Bei Ling, a Boston-based dissident writer and friend, said Gui was in Ningbo and living in rented accomodation.

He said Gui held a 40-minute phone conversation with his daughter on Thursday night.

However, Bei told the Hong Kong Free Press website that his friend was only “half free”.

Angela Gui told the Hong Kong broadcaster RTHK there were “many things that need to be clarified” about her father’s situation and declined to comment further.

Angela Gui told the Hong Kong broadcaster RTHK there were “many things that need to be clarified” about her father’s situation and declined to comment further.

“She said she had received a phone call, but did not confirm it was from her father,” RTHK reported.

A spokesperson for Sweden’s foreign ministry said: “We have received reports from the Chinese authorities that Gui Minhai has been released and we’re doing our best to obtain more information.”

Activists suspect that rather than completely freeing Gui, Chinese authorities have moved him from a detention centre into what they call China’s “non-release release” system.

A spokesperson for Sweden’s foreign ministry said: “We have received reports from the Chinese authorities that Gui Minhai has been released and we’re doing our best to obtain more information.”

Activists suspect that rather than completely freeing Gui, Chinese authorities have moved him from a detention centre into what they call China’s “non-release release” system.

Under this Kafka-esque system, regime opponents are nominally freed but in fact continue to live under the watch and guard of security agents.

“Non-release release” has been the fate of a number of those targeted as part of Xi’s campaign against human rights lawyers, which has seen some of the country’s leading civil rights attorneys spirited into secret detention before “reappearing” in a different form of captivity.

Bei told Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post Gui had informed relatives he wanted to travel to Germany: “But for now, he is not sure if the Chinese authorities will allow him to leave China.

“He will only enjoy true freedom if he is allowed to leave China. If he cannot leave China, he could end up just like Liu Xia,” Bei added, referring to the wife of the late Nobel laureate who has also been living under the watch of security agents since her husband’s death in July.

“Non-release release” has been the fate of a number of those targeted as part of Xi’s campaign against human rights lawyers, which has seen some of the country’s leading civil rights attorneys spirited into secret detention before “reappearing” in a different form of captivity.

Bei told Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post Gui had informed relatives he wanted to travel to Germany: “But for now, he is not sure if the Chinese authorities will allow him to leave China.

“He will only enjoy true freedom if he is allowed to leave China. If he cannot leave China, he could end up just like Liu Xia,” Bei added, referring to the wife of the late Nobel laureate who has also been living under the watch of security agents since her husband’s death in July.

Speaking on Tuesday, the bookseller’s daughter said she was deeply concerned about his wellbeing: “He has allegedly been released but it looks like he is still in some sort of custody... the fact that nobody can contact him and nobody knows where he is, legally constitutes an enforced disappearance, again.”

Exactly what happened to Gui and his bookselling colleagues and why they were targeted remains a mystery.

However, in June last year, one of the other abducted men, Lam Wing-kee, claimed he had been kidnapped by Chinese special forces as part of a coordinated effort to silence criticism of China’s leadership.

Patrick Poon, a Hong Kong-based activist for Amnesty International who is following the case, said: “Definitely he is still under surveillance otherwise the whole thing wouldn’t be so mysterious.”

“We still need to see whether the authorities will allow him to go [to Germany] and it seems to me that he will still be under surveillance for some time before he is allowed to go.”

Poon said it was also unclear whether Chinese authorities had placed conditions on Gui’s release such as “not disclosing what happened to him during his time in detention [or] requiring him not to talk about his case when he leaves China”.

Patrick Poon, a Hong Kong-based activist for Amnesty International who is following the case, said: “Definitely he is still under surveillance otherwise the whole thing wouldn’t be so mysterious.”

“We still need to see whether the authorities will allow him to go [to Germany] and it seems to me that he will still be under surveillance for some time before he is allowed to go.”

Poon said it was also unclear whether Chinese authorities had placed conditions on Gui’s release such as “not disclosing what happened to him during his time in detention [or] requiring him not to talk about his case when he leaves China”.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire