Read The Smog-Inspired Poem That China Can't Stop Talking About

By EMILY FENG

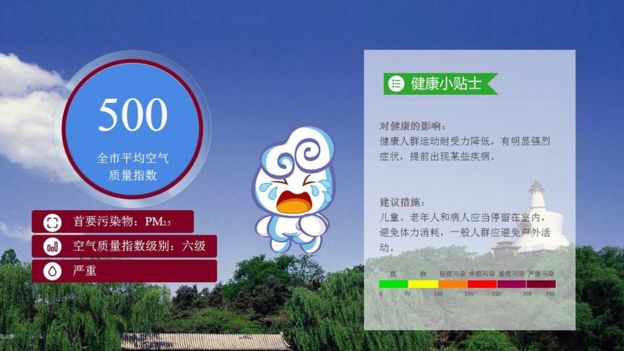

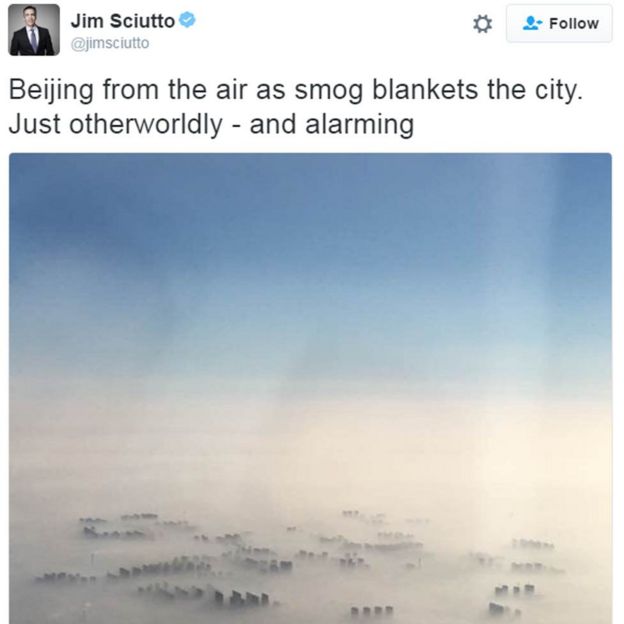

A smog alert day in Dalian, China. The photo was taken on December 19.

A smog alert day in Dalian, China. The photo was taken on December 19.

A poem written by a Chinese surgeon lamenting the medical effects of smog, called "I Long to Be King," is going viral on Chinese social media.

Told from the perspective of lung cancer, the poem takes an apocalyptic note:

Happiness after sorrow, rainbow after rain.

I faced surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy,

But continued to chase my dream,

Some would have given up, but I will be the king.

An

English version of the poem (for full text, see below) ran in the October issue of CHEST Journal, a publication of the American College of Chest Physicians.

Published in Chinese this month, the poem is now striking a chord on Chinese social media.

"I hope the government can look at this problem more and then immediately resolve it, otherwise everyone will move. Or we will die of cancer. Is this the final outcome we face?" asked one commenter on Weibo, China's Twitter-like social media platform.

"I'm infuriated... For the sake of GDP, can we simply ignore the health of our country's people?" wrote another.

Not all commenters appreciated the poem though.

"Europe and the U.S. always most enjoy when Chinese people write about their own underside. The more coarse, the more backward, the higher the chance it wins attention," complained one.

The author of "I Long to Be King" is Dr.

Zhao Xiaogang, deputy chief of thoracic surgery at Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital of Tongji University.

Since the poem has taken off, he has been outspoken in the detrimental health effects of

air pollution.

"The intense rise in lung cancer ... is intimately related to smog," Dr. Zhao

told state media.

In and around Beijing and Hebei province in China's northeast last week, the concentration of air pollutant particles was more than 20 times higher than the level deemed safe by the World Health Organization.

According to the Beijing Environmental Protection Bureau, the city saw 168 days of "polluted" air in 2016.

Cancer is the leading cause of death in China, claiming 2.8 million lives in 2015.

Lung cancer is the country's

leading form of cancer.

The Chinese government, well aware of the simmering discontent, has resolved to clean up the country's smog problem.

Ambitious goals have been set to substantially reign in air pollution by 2020.

And over the past year authorities have fined corporate polluters millions, going as far as detaining several hundred of them.

Yet on Chinese message boards, some commenters don't think the pollution will end any time soon.

"The Hebei countryside is all smog. It is terrible," wrote one commenter.

"It is another way of showing how useless the government is."

Here's the full text of

I Long To Be King:

I am ground glass opacity (GGO) in the lung,

A vague figure shrouded in mystery and strangeness,

Like looking at the moon through clouds,

Like seeing beautiful flowers in the fog.

I long to be king,

With my fellows swimming in every vessel.

My people crawl in your organs and body,

Holding the rights for life or death, I tremble with excitement.

When young you called me "atypical adenomatous hyperplasia",

Then when I had matured, you declared me "adenocarcinoma in situ",

When fully developed, your fearful denomination: "invasive adenocarcinoma".

You forgot my strenuous journey to become the king.

From tiny to strong,

From humble to arrogant.

None cared when I was young,

But all fear me we when full grown.

I've been nourished on the delicious mist and haze,

That sweetly warmed my heart,

Always loving when you were heavy drunk and smoking,

Creating me a cozy home.

When I was less than eight millimeters, I was so fragile,

Waiting for a chance to grow up.

Now, more than eight millimeters, I am more mature,

And considered worthy of notice.

My continuous growth gives me a chance to be king,

As I break through layers of obstacles,

Spanning the mountains and waters.

My fellows march to every corner and occupy every region.

My quest to become king was full of obstacles,

I was cut until almost dead in childhood,

Burned once I'd matured,

And poisoned when older.

Happiness after sorrow, rainbow after rain.

I faced surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy,

But continued to chase my dream,

Some would have given up, but I will be the king.

I long to be king, with fellows and subordinates,

I long to be king, to have people's fear and respect

I long to be king, to dominate my domain,

I long to be king, to direct your fate.