From schoolchildren to political dissidents: how technology is tracking a nation

By Louise Lucas and Emily Feng

Zhejiang Hangzhou No 11 High School, on the fringes of downtown Hangzhou in eastern China, is a green, peaceful-seeming place to learn.

Gazebo-like structures nestle among lush foliage; grey stone sculptures enact eternal dioramas and Japanese maples gently fan placid lakes.

It is also a digital panopticon.

A surveillance system, powered by facial recognition and artificial intelligence, tracks the state school’s 1,010 pupils, informing teachers which students are late or have missed class, while in the café, their menu choices leave a digital dietary footprint that staff can monitor to see who is gorging on too much fatty food.

In May,

The People’s Daily, a state-run media group, tweeted approvingly about the school’s use of cameras to monitor, via their facial expressions, how children were engaging in class.

Had this classroom-based part of the programme not been abruptly halted later that month in the wake of local controversy, it would also have been deployed to predict which pupils (the slouching ones) were likely to underperform.

Welcome to China, where AI is being pressed into service as handmaiden to an authoritarian government.

For many critics, this seems fraught with danger: an Orwellian world where “Big Brother” is always watching, able to spy on anyone from human rights lawyers to political dissidents and persecuted minorities.

For supporters, it is near utopian: a land where criminals and miscreants are easily weeded out, where no one can cheat, where good behaviour is rewarded and the bad punished.

The latter vision is the Chinese government’s stated aim.

By 2020, a national video surveillance network will be “omnipresent, fully networked, always working and fully controllable”, according to an official paper released in 2015.

Visitors try out facial-recognition technology at the China Public Security Expo in Shenzhen last year

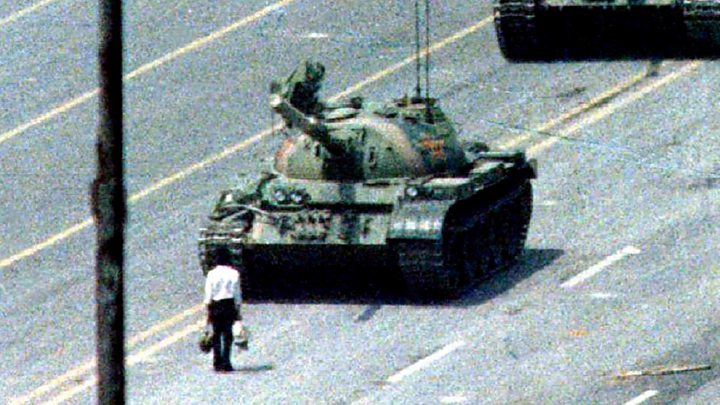

The idea of constant monitoring is not unprecedented in China.

Indeed, the name of the government’s 2020 project —

xueliang, or “sharp eyes” — is a throwback to a Communist party slogan, “The people have sharp eyes”, referencing the

totalitarian ploy of encouraging neighbours to spy on their neighbours.

Under

Mao Zedong, cities were split into grids of socialist work units where access to rations, housing and other benefits was enforced by local spies who reported wayward behaviour from their neighbours.

This system of

social control had in turn been built on a model of communal self-policing introduced centuries before, during the Song dynasty.

Today, the grid system has been revived, manned by an extensive network of volunteer and part-time lookouts.

In more troubled regions such as East Turkestan and Tibet, armed police booths dot street corners. Beijing has about 850,000 “informants” patrolling its streets, according to state media.

Renewing these old-school tactics is a deliberate decision: the government knows that while surveillance technology is advancing rapidly, it is far from perfect.

Cheetah Mobile is a Chinese company whose subsidiary’s facial-recognition vending machine scored top in an international facial-recognition test last year sponsored by Microsoft Research.

But

Fu Sheng, its founder and chief executive, concedes it has a long way to go in terms of spotting faces in crowds.

“The human is an excellent product,” he tells the FT.

“No technology can exceed it.”

That may not matter.

When the British philosopher

Jeremy Bentham envisaged his panopticon penitentiary in the late 18th century — a circular building with an inspection tower at its centre — the idea was that inmates would never know if they were being observed or not.

This “simple idea in architecture” would offer “a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind”, Bentham wrote.

For some analysts looking at the impact of China’s growing surveillance state, any technological shortcomings are incidental.

Like the panopticon itself, it is the fear of being watched that is the most powerful tool of all.

“There’s a wave of enhanced surveillance going on worldwide,” says

Rogier Creemers, who studies Chinese governance at Leiden University.

The difference in China is the historical context: “Liberal democratic institutions are based on the notion that state power must lie in the hands of the population. There are things the state is just not supposed to know or do,” he says.

“China starts from a different point of view — that a strong empowered state is necessary, in order to drag the nation forward. In China, surveillance is almost a logical extension of what the state is supposed to do, because the state is supposed to keep people safe.”

Feng Xiang is translating the Old Testament book of Jeremiah when the FT visits his office at Beijing’s Tsinghua University.

A prominent legal scholar, he has been studying AI and its implications for jobs, society and capitalism in China.

His view is a gloomy one.

As he sees it, public surveillance via CCTV cameras is being rapidly supplemented by a range of

more insidious data collectors-cum-tracking devices: the smartphones in almost half of all Chinese citizens’ pockets.

This will eventually create a world devoid of privacy.

“It’s not like

George Orwell’s

1984, but it’s like a new way of life,” says Feng, noting that even a hike in a scenic park or up a mountain in China today can involve mandatory fingerprinting by police. “In the old days at least you had somewhere you could hide, or where you can do your private things. But now the assumption is people know where you are.”

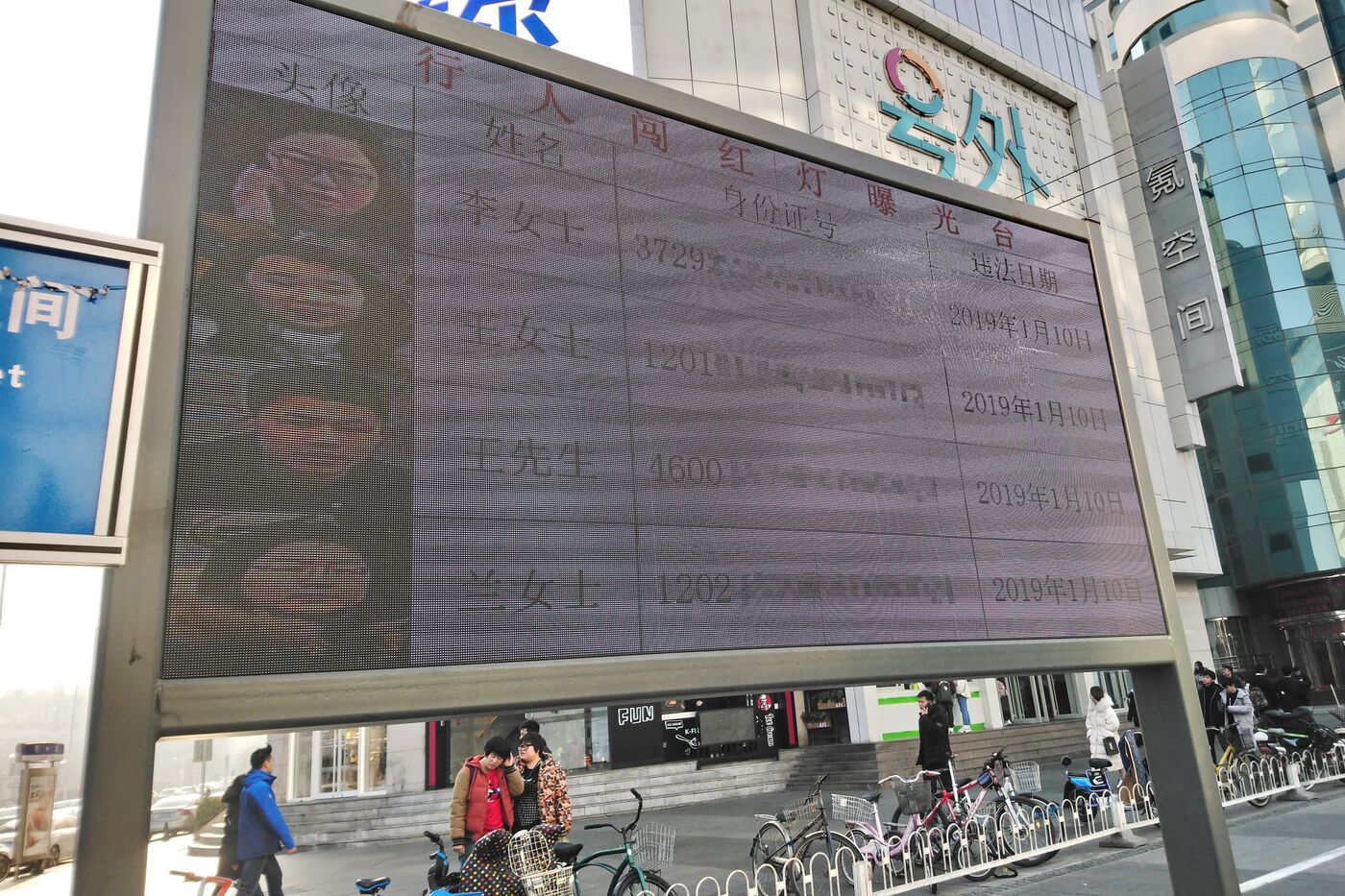

Against the backdrop of deepening surveillance, the Chinese government is introducing a “

social credit system”.

First described in an official document in 2014 and now being piloted in various forms in several cities, the idea is that people will ultimately be scored based on past behaviour, taking in misdemeanours such as traffic offences and court records.

At present, a good financial credit score, handed out by some companies and operating rather like a loyalty programme, can confer benefits such as waived deposits on shared bikes or preferential loan rates.

A poor social credit score, by comparison, could jeopardise a university place, rule out certain jobs and even limit travel: more than 10.5 million people have been barred from buying airline or high-speed train tickets, according to the Supreme Court, since a debtors blacklist was launched.

Meanwhile, the technology by which the government can track people is constantly evolving.

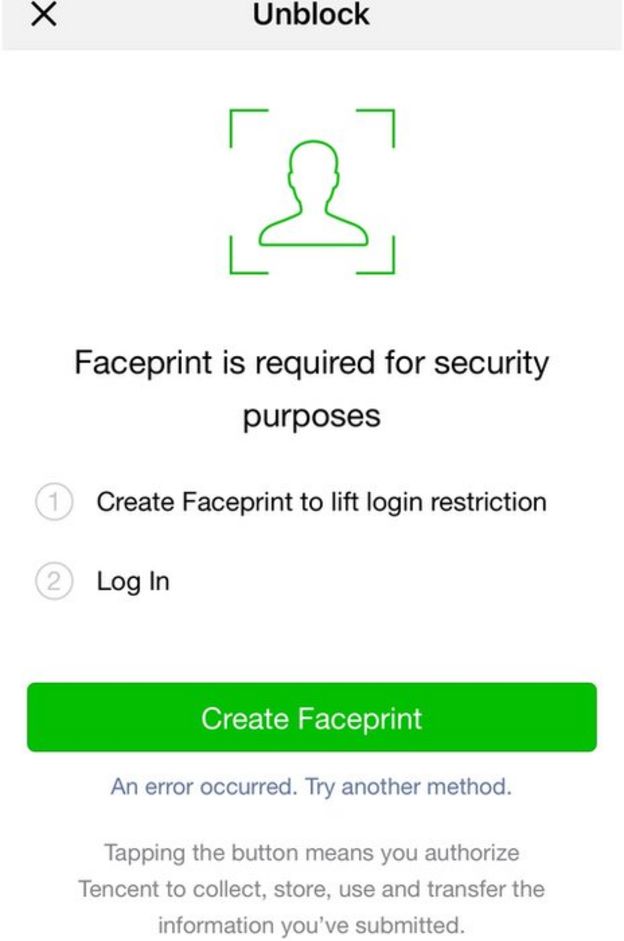

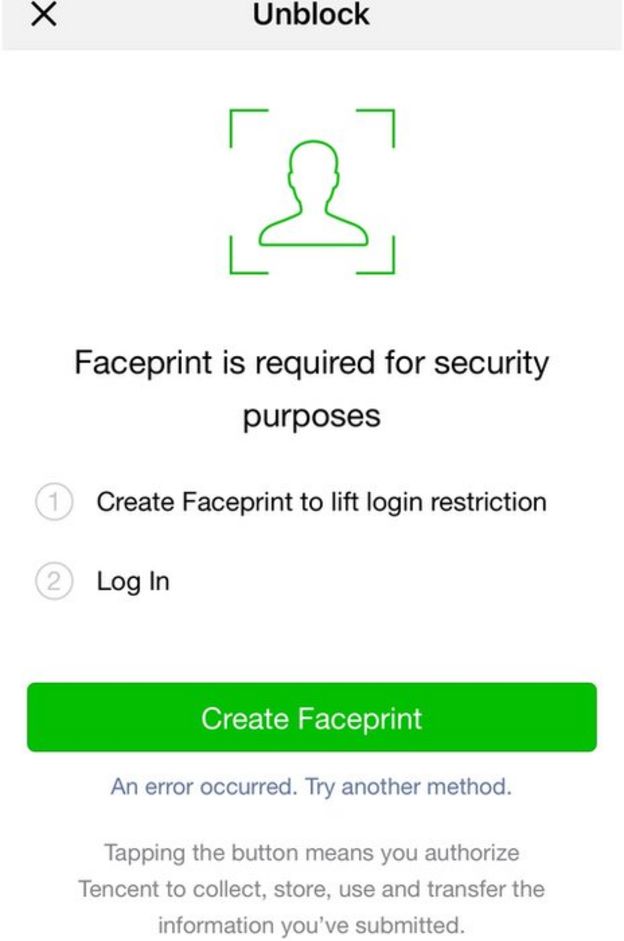

Facial recognition is increasingly used to unlock smartphones in China, and thanks to its multiple commercial applications — from allowing easy payment in a grocery store to home security — it has attracted a slew of venture capital from across the world.

One tech banker dismisses facial recognition to the FT as “kindergarten stuff” compared with what will come next.

Police in Zhengzhou wearing AI-powered smart glasses with facial-recognition capability in April this year

Some of China’s leading facial-recognition players, for example, are now moving into gait recognition.

Hanwang Technology was an early entrant in the field: it was forced to rethink its fingerprint-recognition technology when the Sars epidemic of 2003 left people in China terrified of physical contact.

“We can see the human figure and his gait, so if his cap is pulled down [we] can still recognise him,” explains

Liu Changping, president of the Beijing-based company.

The Chinese authorities already have a decent video database to build on, he adds: “If [someone] was put in prison before, there’s video of him walking around.”

Although China is expanding its surveillance network nationwide, it is in the western region of East Turkestan that the technology is being put to its most extreme use.

The region has been closely policed since 2009, when deadly riots broke out between the 11 million-strong Muslim Uighur population and the minority Han Chinese.

East Turkestan is a vast region, and a relatively poor one, making the multitude of gleaming cameras and sophisticated technology — inside bazaars, schools and even mosques — all the more incongruous amid the expanses of desert and empty roads.

Residents were unwilling to talk on the record about their experiences, for fear of repercussions, but it is clear that normal life has changed irrevocably for the Uighurs.

Tahir Hamut, a Uighur poet and film-maker who fled China and is now based in the US, tells the FT about the day he and his wife were ordered to visit their local police station and leave voice recordings, fingerprints, DNA swabs and, of course, high-resolution video footage of their faces making various expressions.

“I am a director, I make films, and I have seen many kinds of cameras. But I had never seen a camera that strange. They adjusted [the] camera to my eye level. They had me look up and look forward and down, left and right and back,” Hamut recalls.

“They did the same for females . . . they had the women pucker their lips and filmed that. Every step had to be completed perfectly; each expression could not be done too quickly or slowly. If you made a face too fast, the computer would ask you to stop and have you repeat it again. I had to try many times. Many people had to spend an hour to complete this facial filming.”

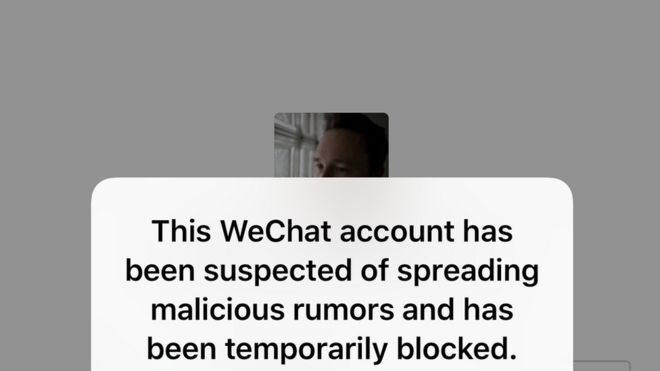

Mandatory surveillance software is installed on residents’ mobile phones to scan for Islamic keywords and pictures.

Some people told the FT that anyone found to have shared illicit material would be sent to the region’s extensive network of extralegal detention camps, where hundreds of thousands of Uighurs have already been imprisoned.

Making too many phone calls to or from anywhere outside of East Turkestan can also result in detention.

As a result, Uighurs living in East Turkestan can go years without speaking to family members working in coastal cities like Beijing or Shanghai.

Facial recognition, intrusive as it is, is only one of the tools the authorities are using to monitor residents.

Last year police were told to conduct DNA swabs, iris scans and blood tests using a specially designed mobile app and health checks, in order to build a region-wide biometric database.

None of this is cheap.

Overall public security spending in the region was Rmb57.95bn ($9.16bn) in 2017, a 10-fold increase over the previous decade.

That has proved a windfall for Chinese security companies.

The government’s investment in public-private partnerships in security has also increased, from $27.3m in 2015 to at least $1.1bn in 2017, based on a tally of existing public tenders and Bank of China data.

Among the largest of these privately funded projects is in East Turkestan’s Shache county, where almost 100 people were killed in 2014 in what state media called a terrorist attack.

The network there will include a video surveillance centre, cloud storage facilities and a drone system.

Smaller companies are also getting a slice of the action, especially government-backed start-ups with the right connections.

Meiya Pico, a private company based in the coastal Fujian province, was selected to develop a desktop version of the mobile-surveillance software that East Turkestan residents were forced to download this year.

The software is now installed on the computers of all public companies and academic institutions. Several East Turkestan academics told the FT that authorities are now alerted if illicit files are accessed.

Meiya Pico’s management frequently meets with high-level officials from the Communist party and the state security apparatus, according to articles and pictures on its website.

Indeed, many Chinese tech companies talk proudly of working to further the government’s aims.

“Our business is dictated by the political requirements of our country. ‘Maintaining stability’ is China’s national security priority so East Turkestan really needs our products. The province is our largest client by far,” says

Wang Wufei, a sales director at X-Face, a Shenzhen-based company that makes facial-recognition software and hardware.

In June, X-Face won a contract to supply 200 security checkpoints in East Turkestan.

Scarier still is what comes next.

A Shenzhen start-up making grenade-bearing drones predicts the East Turkestan authorities will become its largest client.

Another, East Turkestan-based Zhenkong, which specialises in signal-interference technology and has received funding from the East Turkestan border police, sounds a bellicose note.

“The government needs entrepreneurs like us,” says

Ge Guangxu, its president.

“There is no second place in war. We need to be prepared.”

Three centuries ago, Jeremy Bentham suggested his panopticon would lead to “morals reformed . . . industry invigorated . . . public burthens lightened”.

China’s facial-technology players sound an eerily similar note.

Megvii and SenseTime, two of the country’s biggest facial-recognition companies, claim their technology has apprehended thousands of criminals — all without the need for armies of people to watch hours and hours of CCTV footage.

Both have attracted billions of dollars in funding, from Chinese and Russian state funds as well as stars of the Chinese tech scene such as Alibaba.

A statue in honour of Mao Zedong next to CCTV cameras in Tiananmen Square, Beijing

Qi Yin, co-founder and chief executive of Megvii, notes the myriad uses of his company’s Face++ technology, such as in fintech payments.

But for him, surveillance is king: “I believe this will be the largest one in the next three years.” Megvii counts on the government for 40 per cent of its business and describes its work as profiling rather than just identifying.

Someone who regularly appears in video from a subway station but is not an employee could be a thief, says

Xie Yinan, a vice-president at Face++, and the information — in the form of code — is sent to the police.

One of the surveillance industry’s recent — and much publicised — success stories took place at a pop concert in eastern China.

While

Jacky Cheung, a Hong Kong pop star (rebranded a “fugitive trapper” by the Chinese media) crooned, cameras were automatically sweeping the audience.

Facial-recognition technology picked out four men accused of crimes — including a ticket scalper and a greengrocer accused of a Rmb110,000 potato scam in 2015.

“Smiling as he approached his idol, he did not realise he had already been spotted,” Jiaxing police gloated in a social-media post.

Aside from its uses in law enforcement, AI-aided surveillance is also being touted as a tool for industry.

Hanwang Technology, China’s grandfather of facial recognition, has sold its surveillance system to construction sites, enabling managers to track how many hours workers are on site and who is slacking.

Another company, LLVision, produces smart sunglasses with built-in facial recognition; these became famous after police in Zhengzhou were photographed wearing them to monitor travellers at train stations earlier this year.

But the company has also been supplying them to manufacturing plants for use in time management and quality control.

“[Even] if you have 10,000 people checking [machines and workforces] globally, they cannot manage and audit and analyse their checking,” says

Fei Wu, chief executive and founder of LLVision.

“Nor can you see that worker A is working faster than worker B, or how you get more people to work like worker A.”

Wu, a graduate of the UK’s Birmingham University, raised money to produce the sunglasses through crowdfunding and spent three years trialling them.

They have been worn by surgeons in theatre to record or broadcast surgery.

There is even demand among insurers, he says, to use the glasses to recognise cows — farmers have been known to claim insurance on the same deceased bovine twice.

But, as with so many other Chinese companies in this field, a key client for LLVision is the Public Security Bureau.

Think of it, says Wu.

There are almost 1.4 billion people in China.

“But the PSB is done by a few million people. Medical treatment is done by a few million people. Education is done by a few million people . . . There’s a huge gap to fill, so tech must play a big role.”

As the technology to enable mass surveillance and identification becomes more sophisticated, governments across the world will face dilemmas over when and how to use it.

One overseas minister on a trip to China was awed by the technology he was shown, according to Wu, briefly fretting at his country’s strict privacy rules before concluding that in the case of a wanted criminal, everyone would want him to be caught.

Germany unleashed a wave of criticism when it began piloting facial recognition to help track and catch suspected terrorists, while the UK’s independent CCTV watchdog wrote to police chiefs last year raising concerns about the increasing use of facial-recognition technology to monitor crowds. Earlier this year, about 40 civil liberties groups wrote to Amazon urging it to halt sales of its Rekognition software, which the company has promoted as offering “real-time face recognition across tens of millions of faces and detection of up to 100 faces in challenging crowded photos”.

The product, which has been sold to a number of US police forces, “poses a grave threat to communities, including people of colour and immigrants”, the campaigners said.

Then there are China’s own exports, particularly to developing countries under the “ One Belt One Road” initiative.

One such deal, to Zimbabwe, could highlight another key problem with facial-recognition technology, which learns according to the data it is fed: an MIT and Stanford University study found error rates of 20-34 per cent for determining the gender of darker-skinned women compared with less than 1 per cent for light-skinned men.

The rise of mass surveillance yields reams of data, and therein lies one of the big dangers for any country going down this road, says

Nuala O’Connor, chief executive of the US-based Center for Democracy and Technology.

“The risks are the creation of a pervasive and permanent database of individual images for law enforcement, but then used for other purposes, perhaps by government actors,” she says.

Some 530 camera and video surveillance patents were filed by Chinese groups last year, according to the research firm CB Insights — more than five times the number applied for in the US.

Unhindered by worries about privacy or individual rights, China’s deepening specialism has attracted global customers and investors.

“The surveillance industry is still in the growth phase,” proclaimed analysts at Jefferies, the New York-based investment bank.

Hikvision, a company majority owned by two Chinese state entities whose surveillance systems have been used everywhere from East Turkestan to US military bases, was selected to join the MSCI Emerging Markets Index — a global equity benchmark — in June.

Its Chinese-listed shares have risen nearly fivefold over five years.

In Hangzhou, a start-up called Rokid is preparing to release augmented-reality glasses next year. Outside its lakeside office, the company’s founder

Mingming Zhu — known as Misa — demonstrates a prototype pair to the FT.

The glasses are aimed at consumers rather than law enforcement: walking into a party, for example, their facial-recognition technology means you could immediately see the names of guests superimposed above their heads; the glasses could potentially also add information from their social-media feeds.

They look cool, but there is something spooky about getting the lowdown on people without so much as a “hello”, and Misa sounds a note of caution.

“We are making something happen but we have to be very careful. With AI we have a bright side and a dark side. The most difficult thing you are working on right now might bring you to someplace wrong.”

Before he became a billionaire,

Before he became a billionaire,