China's creative GDP numbers: Why does it even bother?

By Stephen Letts

To the absolute surprise of no one, Chinese economic growth came in at an annualised growth rate of 6.7 per cent in 2016.

There was a moderate surprise that annualised fourth quarter figure came in at 6.8 per cent, but not enough to shift sentiment significantly.

By happy coincidence the 2016 result not only lines up with Xi Jinping's call at the World Economic Forum in Davos that it would be thereabouts, but also is right in the middle of the 6.5 to 7 per cent target band drummed up at the National People's Congress in March last year.

The quality of Chinese GDP data is often questioned, given the National Bureau of Statistics can pull together all the threads of the world's second biggest economy into a coherent narrative just three weeks after the quarter ends.

The admission this week from the boss of Liaoning province that the GDP books for his steel and coal-dominated jurisdiction had been cooked for years has not helped matters.

The National Audit Office found revenues from Liaoning's industries and state-owned enterprises were at least 20 per cent higher than what should have been reported between 2011 and 2014, with 2013 representing the peak in creative accounting for one area at 130 per cent over the odds.

To be fair, the practice appears to be frowned on.

The head of the NBS seems to be getting grumpy with this suspect reputation, warning local officials -- who funnel the raw data to the central statisticians and whose chances of promotion are linked to meeting economic targets -- dodgy accounting is a very "serious" offence and culprits would be punished.

The old boss in Liaoning who was allegedly responsible for overstating the industriousness of his patch has been arrested and is facing a trial later this month.

Liaoning, now equipped with a fresh and more credible approach to statistics, is the first and still only province to have fessed up to sliding into recession in 2016.

China's growth rate slows as economy grows

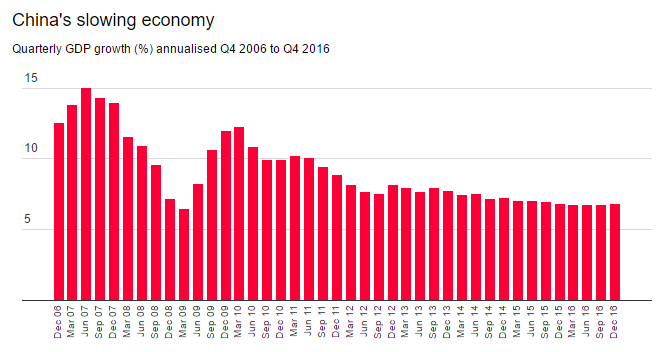

Despite the dubious nature of the numbers a trend has been established; China's economic growth is slowing.

For the past six years, since GDP growth came in at 10.6 per cent in 2010, the economy has been steadily decelerating.

Growth last year was slower than at any time since 1990.

Much of that is due to the fact that the economy is that much bigger.

However, authorities are quite accepting of the inevitability of the situation.

As the chief of China's National Development and Reform Commission, Xu Shaoshi, recently pointed out, a 6.7 per cent -- or 5 trillion yuan ($1 trillion) -- expansion in 2016 equated to growth of 10 per cent in 2011.

The perils of reporting on China's GDP

By Stephen McDonell

Whenever China's GDP figures are released, foreign correspondents fly into action with plenty of analysis about what they might mean.

Does the Chinese economy appear to be stronger or weaker than previously thought?

Where is steel production?

What about the explosion in service industries?

Of course there are the international implications: What do the numbers mean for other economies?

Will Asia's powerhouse look to buy greater volumes Australian iron ore?

Could a growing consumer sector mean more tourists heading to France or Vanuatu?

Then we have to remind ourselves… hang on!

Unlikely but possible

Plenty of economists think that GDP is a massively flawed form of measuring the health of any economy but in this country it is even worse.

There is significant proportion of China watchers who don't believe the GDP figures are real at all.

For example, in 2016, the country's (year on year) GDP was exactly 6.7% for three quarters in a row.

Suspicion regarding growth statistics in the Middle Kingdom is not a new phenomenon.

'Deception'

For years, some provinces are thought to have been artificially inflating their numbers in order to create an appearance of improved economic performance on the part of their local leaders.

Others may have underestimated their growth so as to attract more favours from the national government.

In 2012 when you added the GDP of all provinces together this came to a greater number than the national total.

Now, for the first time, we have official confirmation that GDP here has been fabricated.

According to the Governor of Liaoning, Chen Qiufa, his province has been "involved in a large-scale financial deception" from 2011 to 2014.

He said that fake data from city and county level officials misled the central government about the area's economy.

His announcement was made a meeting of the local legislature giving it even more gravitas.

Alternatives?

If China's GDP is not to be trusted then how to judge this country's economic health?

Some analysts turn to electricity consumption or seaborne cargo believing that these are actual measurable indicators of activity expanding or contracting.

Other potential yardsticks could include building construction per square metre or domestic freight volumes.

Using these measures there are those who think that, in recent years, China's actual GDP should have dropped much more dramatically from 8% down to more like around 4% rather than just below 7%.