By Tania Branigan

Pelamis wave energy equipment in the water at Leith docks in Edinburgh.

It was once renowned as the home of the four great inventions: paper, gunpowder, printing and the compass.

These days, China is more often portrayed as a land of copycats, where you can buy a pirated Superdry T-shirt or a HiPhone and where smaller cities boast 7-12 convenience stores, Teabucks outlets and KFG fried chicken shops.

Behind the startling brand infringement on display in markets and shopping streets lies a deeper intellectual property issue.

Behind the startling brand infringement on display in markets and shopping streets lies a deeper intellectual property issue.

Chinese entities have consistently sought to play catch-up by piggy-backing on other people’s technological advances.

They have pursued software, industrial formulas and processes both through legitimate means – hiring in expertise, buying up startups, tracking publicly available information – and questionable or downright illegal ones: digging genetically modified seeds out of the fields of Iowa so they can be smuggled on a Beijing-bound flight, or paying for details of a specialised process for making a whitening pigment used in Oreos, cosmetics and paper – which sounds like a niche concern until you learn that the titanium dioxide market is worth $12bn a year.

The British carmaker Jaguar Land Rover is suing a Chinese firm for copying its Range Rover Evoque, in the latest of several motor industry cases.

The British carmaker Jaguar Land Rover is suing a Chinese firm for copying its Range Rover Evoque, in the latest of several motor industry cases.

In the best known, China’s Chery reached an undisclosed settlement with General Motors over cars so similar that the doors were interchangeable.

That case had one really striking feature: when GM approached Chinese manufacturers detailing the components they would need for the Matiz, they were told that Chery had already ordered identical parts.

This week came the curious case of Pelamis Wave Power, an innovative Scottish company which lost several laptops in a burglary after being visited by a 60-strong Chinese delegation – and then noticed the launch of a strikingly similar project in China a few years later.

This week came the curious case of Pelamis Wave Power, an innovative Scottish company which lost several laptops in a burglary after being visited by a 60-strong Chinese delegation – and then noticed the launch of a strikingly similar project in China a few years later.

Chinese experts had certainly demonstrated a close interest in the work of Pelamis.

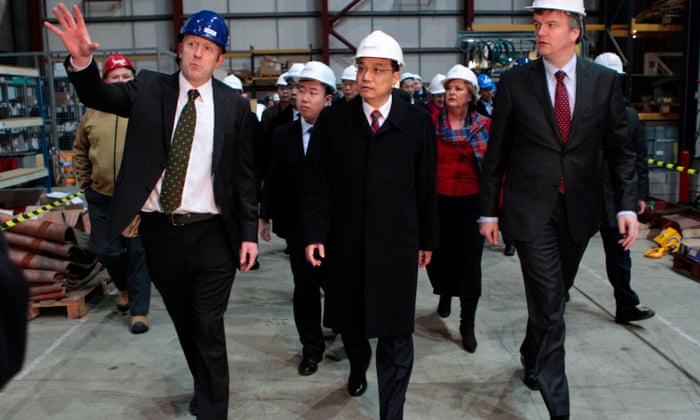

Li Keqiang, now Chinese premier, visits the Pelamis Wave Power factory in 2011.

Whether engineers had been working along similar lines, were paying close attention to what Pelamis had made public, or somehow obtained information by other means is impossible to say.

What is certain – say western governments, business experts, analysts and security experts – is that Chinese businesses are routinely benefiting from the theft of intellectual property.

Companies doing business in China are routinely advised to take clean laptops rather than their usual work devices on trips; to ensure that their work is protected with patents and trademarks internationally; and to be careful about the information they hand over to partners or potential manufacturers.

But their greatest vulnerability is operating in the age of the internet.

But their greatest vulnerability is operating in the age of the internet.

In 2012, Keith Alexander, then director of the US National Security Agency, described commercially targeted cyber-attacks as “the greatest transfer of wealth in history”.

The following year, a commission suggested such intrusions cost the US $300bn a year – with China responsible for up to 80%.

They range from phishing expeditions to narrowly targeted approaches – and even attacks designed to find out what legal and other means firms are using to challenge earlier thefts.

China is consistent and angry in its denials of state-sanctioned industrial espionage: “The Chinese government does not engage in theft of commercial secrets in any form, nor does it encourage or support Chinese companies to engage in such practices in any way,” Xi Jinping said last year.

Chinese firms – even state-owned ones – are not always acting at the behest of officials, still less in the interests of China per se.

China is consistent and angry in its denials of state-sanctioned industrial espionage: “The Chinese government does not engage in theft of commercial secrets in any form, nor does it encourage or support Chinese companies to engage in such practices in any way,” Xi Jinping said last year.

Chinese firms – even state-owned ones – are not always acting at the behest of officials, still less in the interests of China per se.

But security experts have linked commercial incursions to People’s Liberation Army buildings and personnel and Nigel Inkster, formerly of MI6 and author of China’s Cyber Power, observes: “It’s safe to say that there’s been a general policy imperative to catch up with the west technologically, by whatever means.”

Not only are there clear international agreements on intellectual property, there is also vastly more to steal, the internet makes it much easier to do so – and the speed with which breakthroughs are seized upon by others is increasing all the time.

Not only are there clear international agreements on intellectual property, there is also vastly more to steal, the internet makes it much easier to do so – and the speed with which breakthroughs are seized upon by others is increasing all the time.

The Chinese intellectual property regime has developed rapidly: Xiaobai Shen, an expert on intellectual property and business at Edinburgh University, says courts could soon be overwhelmed by the number of domestic cases.

But foreign firms and governments still struggle to pursue cases.

In the titanium dioxide case, an individual was jailed in the US – but prosecutors were unable to serve documents on the Chinese firm concerned.

That has prompted pushback at state level.

That has prompted pushback at state level.

In 2014, the US Justice Department announced it was charging five Chinese military officers with stealing trade secrets.

Just over a year later, following the threat of sanctions, China signed landmark deals with the US and then the UK, agreeing not to conduct or support hacking and intellectual property theft for commercial gain; it was tacitly understood that old-school nation-state spying was still on the cards.

Those agreements were greeted with scepticism – but Dmitri Alperovitch of the cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike says intrusions on commercial targets in the “Five Eyes” – the intelligence alliance made up of the US and UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand – have fallen by as much as 90%, with hackers apparently shifting to domestic targets and Russian entities.

“Prior to the agreement, we have seen pretty much every sector of the economy targeted: insurance, technology, finance. They have scaled back,” he says.

Those agreements were greeted with scepticism – but Dmitri Alperovitch of the cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike says intrusions on commercial targets in the “Five Eyes” – the intelligence alliance made up of the US and UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand – have fallen by as much as 90%, with hackers apparently shifting to domestic targets and Russian entities.

“Prior to the agreement, we have seen pretty much every sector of the economy targeted: insurance, technology, finance. They have scaled back,” he says.

Inkster thinks that may mean a focus on different sources, such as human intelligence.

The agreements are also ambiguous, because of the blurry line between commercial and national security interests when it comes to sectors such as food and energy – with China interpreting national security much more broadly than western nations do.