By Hannah Beech

The runway at Dara Sakor International Airport, which a Chinese company is constructing, will be the longest in Cambodia.

DARA SAKOR, Cambodia — The airstrip stretches like a scar through what was once unspoiled Cambodian jungle.

When completed next year on a remote stretch of shoreline, Dara Sakor International Airport will boast the longest runway in Cambodia, complete with the kind of tight turning bay favored by fighter jet pilots.

Nearby, workers are clearing trees from a national park to make way for a port deep enough to host naval ships.

The politically connected Chinese company building the airstrip and port says the facilities are for civilian use.

But the scale of the land deal at Dara Sakor — which secures 20 percent of Cambodia’s coastline for 99 years — has raised eyebrows, especially since the portion of the project built so far is already moldering in malarial jungle.

The activity at Dara Sakor and other nearby Chinese projects is stirring fears that Beijing plans to turn this small Southeast Asian nation into a de facto military outpost.

Already, a far-flung Chinese construction boom — on disputed islands in the South China Sea, across the Indian Ocean and onward to Beijing’s first military base overseas, in the African Horn nation of Djibouti — has raised alarms about China’s military ambitions at a time when the United States’ presence in the region has waned.

Known as the “string of pearls,” Beijing’s defense strategy would benefit from a jewel in Cambodia.

“Why would the Chinese show up in the middle of a jungle to build a runway?” said Sophal Ear, a political scientist at Occidental College in Los Angeles.

“This will allow China to project its air power through the region, and it changes the whole game.”

A Chinese construction project in the Dara Sakor investment zone. China is Cambodia’s biggest investor.

As China extends its might overseas, it is bumping up against a regional security umbrella shaped by the United States decades ago.

Cambodia, a recipient of Western largess after American bombs devastated its countryside during the Vietnam War, was supposed to be firmly ensconced in the democratic political orbit.

But to win his place as Asia’s longest-serving leader, Prime Minister Hun Sen of Cambodia has turned his back on free elections and rule of law.

He excoriates the United States while warmly embracing China, which is now Cambodia’s largest investor and trading partner.

Down the coast from Dara Sakor, American military officials say, China has reached a deal for exclusive rights to expand an existing Cambodian naval base, even as Beijing denies military intentions in the country.

“We are concerned that the runway and port facilities at Dara Sakor are being constructed on a scale that would be useful for military purposes and which greatly exceed current and projected infrastructure needs for commercial activity,” Lt. Col. Dave Eastburn, a Pentagon spokesman, said by email.

“Any steps by the Cambodian government to invite a foreign military presence,” Colonel Eastburn added, “would disturb peace and stability in Southeast Asia.”

Raising a billboard for a Dara Sakor construction project. The Cambodian government says the area of southwestern Cambodia will be a global logistics hub.

An American intelligence report published this year raised the possibility that “Cambodia’s slide toward autocracy,” as Hun Sen tightens his 34-year grip on power, “could lead to a Chinese military presence in the country.”

This month, the United States Treasury Department accused a senior general linked to Dara Sakor of corruption and imposed sanctions on him.

Hun Sen denies that he is letting China’s military set up in Cambodia.

Instead, his government claims that Dara Sakor’s runway and port will transform this remote rainforest into a global logistics hub that will “make miracles possible,” as Dara Sakor’s promotional literature puts it.

“There will be no Chinese military in Cambodia, none at all, and to say that is a fabrication,” said Pay Siphan, a government spokesman.

“Maybe the white people want to hold Cambodia back by stopping us from developing our economy.”

The home of Ban Em’s family in Chamlang Kou village will be razed to make way for a “military port built by the Chinese,” her husband, Thim Lim, said Cambodian officials told him.

An Unusual Land Deal

In July, armed men in military uniforms arrived at the wooden house of Thim Lim, a fisherman who lives in Cambodia’s largest national park.

Leave, they demanded.

Mr. Thim Lim said he was told by officials from the Ministry of Land Management that his home would be demolished next year to make way for a “military port built by the Chinese.”

Other villagers who attended the meeting confirmed his account.

Land officials wouldn’t comment.

“China is so big that it can do what it wants to do,” Mr. Thim Lim said.

Mr. Thim Lim’s land is part of the Dara Sakor concession leased more than a decade ago to Union Development Group, an obscure Chinese company with no international footprint apart from its 110,000-acre Cambodian acquisition.

Villagers sorting fishing nets in Chamlang Kou. It is part of the Dara Sakor land concession, which was leased to a Chinese company under unusual terms.

The deal was questionable from its inception.

With no open bidding process, Union Development was handed a 99-year lease on a concession triple the size of what Cambodia’s land law allows.

The company was exempted from any lease payments for a decade.

On Dec. 9, Gen. Kun Kim, a former military chief of staff, and his family became targets of United States Treasury sanctions for profiting from relationships with a “China state-owned entity” and for having used “soldiers to intimidate, demolish and clear out land.”

While the Chinese firm was not named, rights groups and local residents said it was Union Development.

Presiding over the signing of the Dara Sakor deal in 2008 was Zhang Gaoli, once among China’s top leaders.

The company’s promotional materials call the development “the largest seashore investment project not only in Southeast Asia but in the world.”

Even with generous lease terms, the one part of Dara Sakor that has been built, a resort complex, is languishing.

On a recent day, the golf course was empty and the casino deserted.

The marina restaurant attracted one Chinese family, which had brought seafood in a plastic bag to avoid paying resort prices.

Instead of retreating from a faltering venture, Union Development has doubled down.

The new construction at Dara Sakor includes a 10,500-foot runway and a deep-sea port able to handle 10,000-ton vessels.

The Dara Sakor Resort, which includes Koh Kong Casino, has seen little tourist traffic.

Who controls the venture remains opaque.

For years, Union Development claimed Dara Sakor was entirely private.

Yet Gen. Chhum Socheat, Cambodia’s deputy defense minister, told The New York Times that the nation’s civil aviation authority was running the airport project, meaning that it could not possibly be linked to the Chinese military.

Sin Chansereyvutha, a spokesman for the State Secretariat of Civil Aviation, however, said that “we don’t have an agreement” for Dara Sakor airport.

In May, Union Development handed Hun Sen, the prime minister, a check for $1 million for the Cambodian Red Cross, which his wife runs.

The company’s headquarters in Phnom Penh, the Cambodian capital, are decorated with pictures of Gen. Tea Banh, Cambodia’s defense minister, striding across Dara Sakor’s golf course.

Union Development Group’s main office is next to the defense minister’s home.

Construction at the Chinese-built Sealong Bay International Beach Resort development, near Cambodia’s largest naval base.

‘China Is Looking for Our Prosperity’

Less than 50 miles from Dara Sakor, another nearly empty Chinese-built development rises from another national park.

The Sealong Bay International Beach Resort has sea views and Chinese chefs.

But it’s the project’s neighbor that has been attracting the most attention: Ream Naval Base, Cambodia’s largest.

“All these projects thrive off ambiguity because you’re never really sure what’s going on,” said Devin Thorne, co-author of “Harbored Ambitions,” a study by the Center for Advanced Defense Studies, a Washington research group, on China’s maritime strategy in the Indo-Pacific.

“You’ll have five Chinese port proposals; two of them fall through and then suddenly there’s one more next door. It’s really hard to keep track of.”

In July, The Wall Street Journal reported on a secret draft agreement to give China exclusive access to part of Ream Naval Base for 30 years.

Cambodian ships at Ream Naval Base. American officials suspect there are plans for Ream “that involve hosting Chinese military assets.”

Speculation about Ream intensified this year when the United States, which had acceded to a Cambodian request to refurbish U.S.-funded training and boat maintenance facilities on the base, was notified that the Cambodians no longer wanted the Americans’ help.

“The withdrawal of the request six months later was surprising and raises questions about the Cambodian government’s plans for the base,” said Colonel Eastburn, the Pentagon spokesman.

General Chhum Socheat, the deputy defense minister, denied that Cambodia had asked the Americans for money for Ream.

“We are frankly fed up,” he told The Times.

“Do we have to ask the United States to develop our sovereignty? Do we have to beg the United States to do this project, that one?”

But in a May 8 letter to the Cambodian Defense Ministry, the American defense attaché in Phnom Penh noted that Cambodia had “requested U.S. assistance to conduct repairs and minor renovations to U.S.-provided facilities on the base.”

In a response a month later, a Cambodian defense official replied that “the repairs and renovations of the facilities on the base are no longer necessary.”

In a subsequent letter, Joseph Felter, then the American deputy assistant secretary of defense for South and Southeast Asia, warned General Tea Banh, the defense minister, of suspicions “that this sudden change of policy could indicate larger plans for changes at Ream Naval Base, particularly ones that involve hosting Chinese military assets.”

The defense minister did not answer the letter.

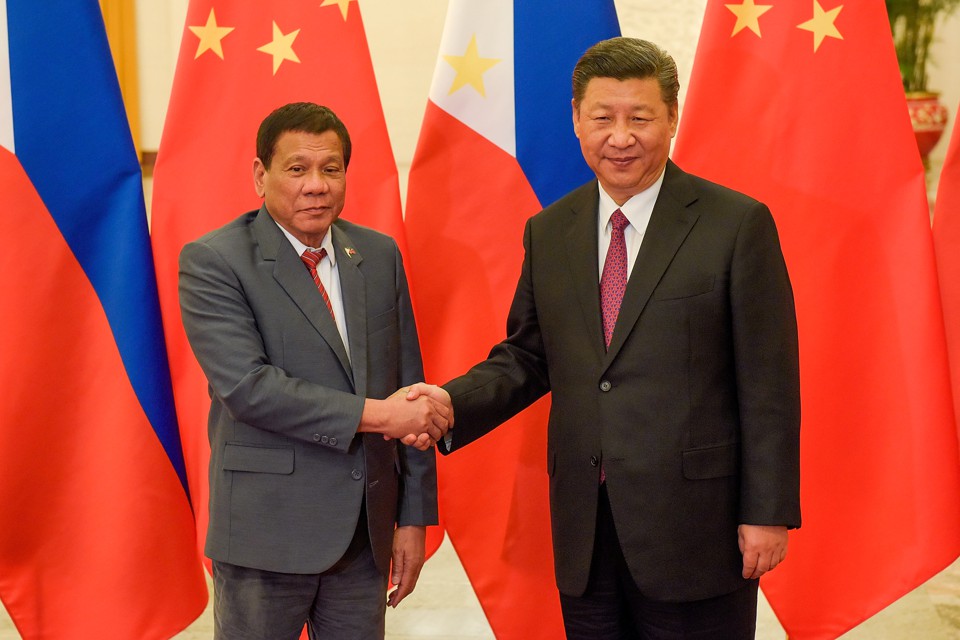

Hun Sen, center, at a groundbreaking ceremony for a Chinese-built bridge in Cambodia. “We are very good friends,” a spokesman for his government said, referring to China.

Hun Sen and his deputies accuse the United States of trying to foment a revolution against his government.

In July, the United States House of Representatives passed a bill seeking to impose sanctions on individuals who have undermined democracy in Cambodia.

Associates of Hun Sen, who has crushed his political opponents, could be among them.

Two years ago, the Cambodian military suspended joint military exercises with the Americans and began partnering with the Chinese instead.

Then, in a further sign of deepening military ties, Hun Sen announced in July that he had spent $240 million on Chinese weaponry.

“If the U.S. Embassy, they don’t like us, they can pack up and leave,” Pay Siphan, the government spokesman, who is a dual Cambodian and American citizen, said in an interview.

“They are troublemakers, and we see it when they look down on Cambodia.”

“China is looking for our prosperity,” he added.

“We are very good friends.”

An empty lifeguard tower on the beach at Dara Sakor Resort.

As China extends its might overseas, it is bumping up against a regional security umbrella shaped by the United States decades ago.

Cambodia, a recipient of Western largess after American bombs devastated its countryside during the Vietnam War, was supposed to be firmly ensconced in the democratic political orbit.

But to win his place as Asia’s longest-serving leader, Prime Minister Hun Sen of Cambodia has turned his back on free elections and rule of law.

He excoriates the United States while warmly embracing China, which is now Cambodia’s largest investor and trading partner.

Down the coast from Dara Sakor, American military officials say, China has reached a deal for exclusive rights to expand an existing Cambodian naval base, even as Beijing denies military intentions in the country.

“We are concerned that the runway and port facilities at Dara Sakor are being constructed on a scale that would be useful for military purposes and which greatly exceed current and projected infrastructure needs for commercial activity,” Lt. Col. Dave Eastburn, a Pentagon spokesman, said by email.

“Any steps by the Cambodian government to invite a foreign military presence,” Colonel Eastburn added, “would disturb peace and stability in Southeast Asia.”

Raising a billboard for a Dara Sakor construction project. The Cambodian government says the area of southwestern Cambodia will be a global logistics hub.

An American intelligence report published this year raised the possibility that “Cambodia’s slide toward autocracy,” as Hun Sen tightens his 34-year grip on power, “could lead to a Chinese military presence in the country.”

This month, the United States Treasury Department accused a senior general linked to Dara Sakor of corruption and imposed sanctions on him.

Hun Sen denies that he is letting China’s military set up in Cambodia.

Instead, his government claims that Dara Sakor’s runway and port will transform this remote rainforest into a global logistics hub that will “make miracles possible,” as Dara Sakor’s promotional literature puts it.

“There will be no Chinese military in Cambodia, none at all, and to say that is a fabrication,” said Pay Siphan, a government spokesman.

“Maybe the white people want to hold Cambodia back by stopping us from developing our economy.”

The home of Ban Em’s family in Chamlang Kou village will be razed to make way for a “military port built by the Chinese,” her husband, Thim Lim, said Cambodian officials told him.

An Unusual Land Deal

In July, armed men in military uniforms arrived at the wooden house of Thim Lim, a fisherman who lives in Cambodia’s largest national park.

Leave, they demanded.

Mr. Thim Lim said he was told by officials from the Ministry of Land Management that his home would be demolished next year to make way for a “military port built by the Chinese.”

Other villagers who attended the meeting confirmed his account.

Land officials wouldn’t comment.

“China is so big that it can do what it wants to do,” Mr. Thim Lim said.

Mr. Thim Lim’s land is part of the Dara Sakor concession leased more than a decade ago to Union Development Group, an obscure Chinese company with no international footprint apart from its 110,000-acre Cambodian acquisition.

Villagers sorting fishing nets in Chamlang Kou. It is part of the Dara Sakor land concession, which was leased to a Chinese company under unusual terms.

The deal was questionable from its inception.

With no open bidding process, Union Development was handed a 99-year lease on a concession triple the size of what Cambodia’s land law allows.

The company was exempted from any lease payments for a decade.

On Dec. 9, Gen. Kun Kim, a former military chief of staff, and his family became targets of United States Treasury sanctions for profiting from relationships with a “China state-owned entity” and for having used “soldiers to intimidate, demolish and clear out land.”

While the Chinese firm was not named, rights groups and local residents said it was Union Development.

Presiding over the signing of the Dara Sakor deal in 2008 was Zhang Gaoli, once among China’s top leaders.

The company’s promotional materials call the development “the largest seashore investment project not only in Southeast Asia but in the world.”

Even with generous lease terms, the one part of Dara Sakor that has been built, a resort complex, is languishing.

On a recent day, the golf course was empty and the casino deserted.

The marina restaurant attracted one Chinese family, which had brought seafood in a plastic bag to avoid paying resort prices.

Instead of retreating from a faltering venture, Union Development has doubled down.

The new construction at Dara Sakor includes a 10,500-foot runway and a deep-sea port able to handle 10,000-ton vessels.

The Dara Sakor Resort, which includes Koh Kong Casino, has seen little tourist traffic.

Who controls the venture remains opaque.

For years, Union Development claimed Dara Sakor was entirely private.

Yet Gen. Chhum Socheat, Cambodia’s deputy defense minister, told The New York Times that the nation’s civil aviation authority was running the airport project, meaning that it could not possibly be linked to the Chinese military.

Sin Chansereyvutha, a spokesman for the State Secretariat of Civil Aviation, however, said that “we don’t have an agreement” for Dara Sakor airport.

In May, Union Development handed Hun Sen, the prime minister, a check for $1 million for the Cambodian Red Cross, which his wife runs.

The company’s headquarters in Phnom Penh, the Cambodian capital, are decorated with pictures of Gen. Tea Banh, Cambodia’s defense minister, striding across Dara Sakor’s golf course.

Union Development Group’s main office is next to the defense minister’s home.

Construction at the Chinese-built Sealong Bay International Beach Resort development, near Cambodia’s largest naval base.

‘China Is Looking for Our Prosperity’

Less than 50 miles from Dara Sakor, another nearly empty Chinese-built development rises from another national park.

The Sealong Bay International Beach Resort has sea views and Chinese chefs.

But it’s the project’s neighbor that has been attracting the most attention: Ream Naval Base, Cambodia’s largest.

“All these projects thrive off ambiguity because you’re never really sure what’s going on,” said Devin Thorne, co-author of “Harbored Ambitions,” a study by the Center for Advanced Defense Studies, a Washington research group, on China’s maritime strategy in the Indo-Pacific.

“You’ll have five Chinese port proposals; two of them fall through and then suddenly there’s one more next door. It’s really hard to keep track of.”

In July, The Wall Street Journal reported on a secret draft agreement to give China exclusive access to part of Ream Naval Base for 30 years.

Cambodian ships at Ream Naval Base. American officials suspect there are plans for Ream “that involve hosting Chinese military assets.”

Speculation about Ream intensified this year when the United States, which had acceded to a Cambodian request to refurbish U.S.-funded training and boat maintenance facilities on the base, was notified that the Cambodians no longer wanted the Americans’ help.

“The withdrawal of the request six months later was surprising and raises questions about the Cambodian government’s plans for the base,” said Colonel Eastburn, the Pentagon spokesman.

General Chhum Socheat, the deputy defense minister, denied that Cambodia had asked the Americans for money for Ream.

“We are frankly fed up,” he told The Times.

“Do we have to ask the United States to develop our sovereignty? Do we have to beg the United States to do this project, that one?”

But in a May 8 letter to the Cambodian Defense Ministry, the American defense attaché in Phnom Penh noted that Cambodia had “requested U.S. assistance to conduct repairs and minor renovations to U.S.-provided facilities on the base.”

In a response a month later, a Cambodian defense official replied that “the repairs and renovations of the facilities on the base are no longer necessary.”

In a subsequent letter, Joseph Felter, then the American deputy assistant secretary of defense for South and Southeast Asia, warned General Tea Banh, the defense minister, of suspicions “that this sudden change of policy could indicate larger plans for changes at Ream Naval Base, particularly ones that involve hosting Chinese military assets.”

The defense minister did not answer the letter.

Hun Sen, center, at a groundbreaking ceremony for a Chinese-built bridge in Cambodia. “We are very good friends,” a spokesman for his government said, referring to China.

Hun Sen and his deputies accuse the United States of trying to foment a revolution against his government.

In July, the United States House of Representatives passed a bill seeking to impose sanctions on individuals who have undermined democracy in Cambodia.

Associates of Hun Sen, who has crushed his political opponents, could be among them.

Two years ago, the Cambodian military suspended joint military exercises with the Americans and began partnering with the Chinese instead.

Then, in a further sign of deepening military ties, Hun Sen announced in July that he had spent $240 million on Chinese weaponry.

“If the U.S. Embassy, they don’t like us, they can pack up and leave,” Pay Siphan, the government spokesman, who is a dual Cambodian and American citizen, said in an interview.

“They are troublemakers, and we see it when they look down on Cambodia.”

“China is looking for our prosperity,” he added.

“We are very good friends.”

An empty lifeguard tower on the beach at Dara Sakor Resort.