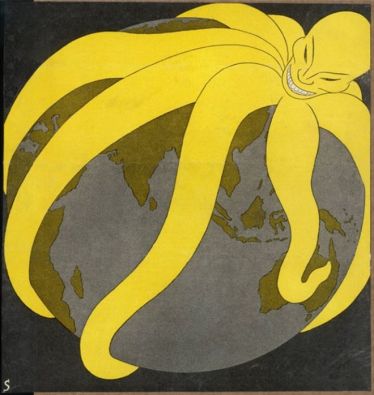

Beijing cannot bend history to its will, but it will try.

By Patrick Mendis and Joey Wang

The key enabler that has allowed Beijing to protect its sovereign claims and project its power has been China’s explosive economic growth.

As it cools, however, major programs such as the BRI will be critical to any future projection of power.

As envisioned, the purpose of BRI is to “promote regional economic cooperation, strengthen exchanges and mutual learning between different civilizations, and promote world peace and development.”

Behind this heady mixture of material, economic, and cultural aspirations, however, there are other hidden motivations not likely to be mentioned in official Chinese literature.

First, China also wants to decrease the dependence on its domestic infrastructure investment and begin moving investments overseas to address the capacity overhang within China.

First, China also wants to decrease the dependence on its domestic infrastructure investment and begin moving investments overseas to address the capacity overhang within China.

It should not come as an astonishment that the key instrument of this investment transfer comes with the Chinese system of “state capitalism,” which has further been solidified by Xi Jinping.

Among the BRI infrastructure development projects, Chinese companies accounted for 89 percent of the contractors, according to a five-year analysis of BRI projects by the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

BRI also parallels numerous regional economic and infrastructure development initiatives such as the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), the Ayeyarwady-Chao Phraya-Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy (ACMECS), and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

BRI also parallels numerous regional economic and infrastructure development initiatives such as the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC), the Ayeyarwady-Chao Phraya-Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy (ACMECS), and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

As the country with the deepest pockets, a number of these member-countries have found Chinese capital too attractive to resist.

Chairing the BIMSTEC this year, Sri Lanka, for example, now finds itself granting China a ninety-nine-year lease at the Hambantota Port as well as approximately fifteen thousand acres of land nearby for an industrial zone to help pay for part of the $1.1 billion it owes China.

Laos and Cambodia—members of ACMECS—are so indebted to China that Australia’s former Foreign Minister Gareth Evans has purportedly opined that they have become “wholly owned subsidiaries of China.”

Some countries have now learned from the Sri Lanka experience and have recognized that the costs far outweigh the benefits.

Bangladesh, for instance, has declined Chinese funding for the much needed “the twenty kilometers-long rail and road bridges over Padma river” and has instead opted to “self-generated funds.” Thailand, under ACMECS, is also working to create a regional infrastructure fund to reduce reliance on China and avoid what has generally been called China’s “debt-trap diplomacy.”

Even outside the immediate domain of the BRI, China is using its wealth to isolate Taiwan diplomatically.

Even outside the immediate domain of the BRI, China is using its wealth to isolate Taiwan diplomatically.

In Latin America , China peeled away El Salvador in August after peeling away the Dominican Republic in May 2018.

With growing Chinese influence in Africa, Swaziland—a tiny landlocked country— remains the only African country to recognize Taiwan after Burkina Faso established diplomatic relations with Beijing in May 2018.

China is also expanding its presence and engagement in the Caribbean with capital investments and infrastructure financing, which have played significantly to China’s advantage given the Caribbean’s proximity to the hurricane belt in America’s backyard.

China is also expanding its presence and engagement in the Caribbean with capital investments and infrastructure financing, which have played significantly to China’s advantage given the Caribbean’s proximity to the hurricane belt in America’s backyard.

The Caribbean—so-called the “Third Border” of the United States—has been neglected even after Congress passed the U.S.-Caribbean Strategic Engagement Act of 2016.

The Trump White House has shown little interest in engaging the Caribbean basin.

Many observers think that the region is “too democratic and not poor enough” to get on the American foreign-policy agenda even though Washington has long noticed the Chinese “inroads” in America’s Third Border region.

Beijing has often hailed the Chinese investments as “win-win.”

Beijing has often hailed the Chinese investments as “win-win.”

However, given that many of these countries both within and outside the BRI are now indebted to China, it is not clear whether the partnership is a win for both China and its counterpart—or China actually wins twice , since

a) it is generally well understood that the switching of allegiance is more monetary than ideological, and

b) the recipient often ends up indebted to China without the means to repay the debt.

Second, China wants to internationalize the use of its currency along BRI and with the new partners of Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean basin.

Second, China wants to internationalize the use of its currency along BRI and with the new partners of Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean basin.

Making the renminbi (RMB) a global currency in 2015 had been one of the highest economic priorities of Beijing’s grand plan.

China and some sixty-five BRI countries—which account collectively for over 30 percent of global GDP, 62 percent of the population, and 75 percent of known energy reserves—are increasingly using the RMB to facilitate trade and infrastructure projects.

Pakistan, for one, has switched from the dollar to the RMB for bilateral trade with China after President Donald Trump publicly attacked Pakistan onTwitter for harboring terrorists.

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) to East Turkestan—as one of the massive projects under the BRI—can now depend upon a steady stream of Chinese capital.

Pakistan can now also minimize the risk of Washington’s threats such as cutting off economic assistance and military support.

Use of the RMB would also help authoritarian regimes like Iran, North Korea, and Sudan to undermine the American-imposed “financial sanctions” on the violations of such norms as human rights, child labor, and human trafficking.

Furthermore, the success of BRI, if achieved, would establish Eurasia as the largest economic market in the world and the changing currency dynamics could initiate a shift in the world away from the dollar-based financial system.

Third, China seeks to secure its energy resources through new pipelines in Central Asia, Russia, and South and Southeast Asia’s deep-water ports.

Third, China seeks to secure its energy resources through new pipelines in Central Asia, Russia, and South and Southeast Asia’s deep-water ports.

Beijing’s leadership for some years has been concerned about its “Malacca Dilemma” as Hu Jintao declared in 2003 that “certain major powers” may control the Strait of Malacca and China needed to adopt “new strategies to mitigate the perceived vulnerability.”

The Strait of Malacca is not only the main conduit connecting the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean to China via the South China Sea but also the shortest sea route between oil suppliers in the Persian Gulf and key markets in Asia.

In 2016, sixteen million barrels of crude oil transited through the Malacca Strait each day, of which 6.3 million barrels were destined for China.

In 2017, China surpassed the United States as the world’s largest crude oil importer.

Therefore, the sustainability and security of energy supplies is a key input not only to China’s domestic stability and economic growth but also to its military operations and, concomitantly, the very legitimacy of the CPC.

Initiatives under the BRI—such as the CPEC to East Turkestan colony, the Kyaukpyu pipeline in Myanmar that runs to Yunnan province, and the ongoing discussions for the proposed Kra Canal in Thailand —are of vital interest to China because they would provide alternative routes for energy resources from the Middle East directly to China that bypass the Malacca Strait.

The BRI will also support the expansion of China’s military bases across the Bay of Bengal, Indian Ocean, and the Arabian Sea.

Global Response Led by Washington

As Beijing’s intentions become clear, the continuing tensions have now revived the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue with Australia, India, Japan, and the United States.

Global Response Led by Washington

As Beijing’s intentions become clear, the continuing tensions have now revived the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue with Australia, India, Japan, and the United States.

Each of these Quad members has its own economic and geostrategic concerns over balancing China’s expanding power and influence with a host of counter-strategies.

President Trump has, for example, signed into law the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act of 2018—a belated expression of America’s commitment to the security and stability of the Indo-Pacific region.

The U.S. Senate has also passed the Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development (BUILD) Act of 2018 to reform and improve overseas private investment to help developing countries in ports and infrastructure.

The U.S. Senate has also passed the Better Utilization of Investments Leading to Development (BUILD) Act of 2018 to reform and improve overseas private investment to help developing countries in ports and infrastructure.

It is also aimed at countering China’s influence and assisting BRI countries with alternatives to China’s “debt-trap diplomacy.”

Viewed in the context of history, China’s rise has been nothing short of meteoric.

Viewed in the context of history, China’s rise has been nothing short of meteoric.

In the sixty-plus years since U.S. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles declared the three principles—that

1) the United States would not recognize the People’s Republic of China,

2) would not admit it to the UN, and

3) would not lift the trade embargo—

China has grown from a veritable economic backwater to one that is now projecting its economic and military power around the world.

China now seeks to create a new set of global norms, while overturning the existing norms that Beijing claims it had no role in creating.

That may be true, but China should remember that those existing international norms have also played a critical role in raising China to where it is today.

War Indications and Warnings

Successive American and Chinese leaders have come and gone.

War Indications and Warnings

Successive American and Chinese leaders have come and gone.

But China’s strategic objectives have remained much the same as they were in 1965 when the CIA concluded, inter alia , that the goal of CPC for the foreseeable future would be to “eject the West, especially the US, from Asia and to diminish US and Western influence throughout the world.”

The CIA further reported that Beijing also aimed to “increase the influence of Communist China in Asia” as well as to “increase the influence of Communist China throughout the underdeveloped areas of the world.”

While tensions remain fraught between Washington and Beijing, the logic of China’s exercise of military power and its willingness to go to war, however, is more nuanced.

While tensions remain fraught between Washington and Beijing, the logic of China’s exercise of military power and its willingness to go to war, however, is more nuanced.

In any confrontation with the United States, Beijing’s strategy will include “creating sufficient doubt in the minds of American strategists” as to the likelihood of winning an armed conflict with China.

In his book, On China, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger concludes that rather than measuring success by the battles won, the Chinese are likely to measure success through “the means of building a dominant political and psychological position, such that the outcome of a conflict becomes a foregone conclusion.”

By its own actions, the United States has helped China all along by sowing doubt among nations in the Indo-Pacific as to Washington’s own commitment to the security and stability of the region.

Security cooperation between the United States and its allies are not intended to “contain China.” Rather, they are aimed to maintain a balance of power in the region to ensure regional stability and no one power overwhelmingly dominates the others.

Security cooperation between the United States and its allies are not intended to “contain China.” Rather, they are aimed to maintain a balance of power in the region to ensure regional stability and no one power overwhelmingly dominates the others.

Whatever claims China has made to a “Peaceful Rise,” it is clear that “peaceful” is ringing somewhat hollow.

The United States should continue to engage allies and friends to maintain a consistent and persistent presence—irrespective of the administration in place—as an expression of its resolve, unity, and commitment to security, peace, and stability in the Indo-Pacific region.

As China continues its military buildup and modernization, the challenge for American negotiators is that intentions may change, but not capabilities.

The fact that the United Kingdom is now seeking to establish military bases in Asia and the Caribbean reflect continuing concerns not only for the United States and the countries of those regions, but also those on the European continent.

In addition, the United States and its allies should firmly apply a unified front in pressuring China and engaging Beijing to respect global norms in areas such as trade, technology transfer, and intellectual property theft.

In addition, the United States and its allies should firmly apply a unified front in pressuring China and engaging Beijing to respect global norms in areas such as trade, technology transfer, and intellectual property theft.

In this regard, it is quite clear that China’s behavior in pursuit of its Made in China 2025 goals is not only a concern for the United States but also for other advanced economies.

In the broader scheme of things, China should measure its ideological priorities against its costs.

If and when China and Taiwan unite, then it will be based upon mutual amity and the belief that it is in the interest of all Chinese people to do so—not through coercion and aggression.

Beijing cannot bend history to its will.