A United States Navy reconnaissance plane on Okinawa, Japan, after a mission last year over the South China Sea. Some analysts say America’s military posture in the disputed sea has hardened under President Trump.

HONG KONG — Southeast Asian countries tend to be deeply reluctant to collectively challenge China’s growing military and economic prowess in their region.

But this week, they appear to be doing just that — by holding their first joint naval drills with the United States Navy.

The drills, which will take place partly in the South China Sea, a site of geopolitical tension, began on Monday.

The drills, which will take place partly in the South China Sea, a site of geopolitical tension, began on Monday.

They were not expected to focus on lethal maneuvers, or to take place in contested waters where China operates military bases.

But the maneuvers follow similar exercises held last year by China and the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations in an undisputed area of the sea, making them a riposte of sorts to Beijing.

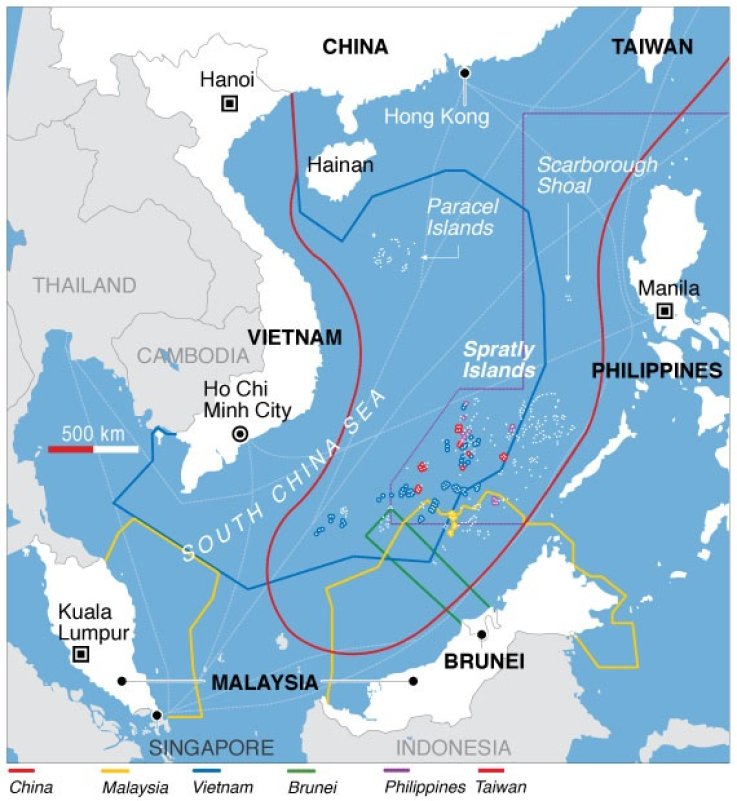

During a summer of heightened tensions over territorial claims, plus an escalating trade war between China and the United States, the drills are being closely watched as the latest move in a high-stakes geopolitical chess match between the superpowers and their shared regional allies.

Some analysts see the drills as part of an incremental hardening of America’s military posture in the South China Sea under President Trump, a strategy that has not been accompanied by additional American diplomacy or incentives for its partners.

“The United States is taking a risk both that its partners will be less inclined to work with it because they are nervous about signaling security cooperation when there’s nothing else there, and that China will continue to advance in the places in which we are absent” on diplomatic and economic fronts, said Mira Rapp-Hooper, an expert on Asian security affairs at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York.

United States Navy sailors monitoring radar and other instruments aboard the guided-missile cruiser U.S.S. Chancellorsville in the South China Sea in 2016.

“So from a basic balance-of-power perspective, we are not holding the line nearly as well as we should be,” she added.

The United States Navy declined to comment on the record ahead of the drills, citing operational sensitivities.

But in a statement late Sunday, the Navy said the drills would include “a sea phase in international waters in Southeast Asia, including the Gulf of Thailand and South China Sea.”

But the maneuvers follow similar exercises held last year by China and the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations in an undisputed area of the sea, making them a riposte of sorts to Beijing.

During a summer of heightened tensions over territorial claims, plus an escalating trade war between China and the United States, the drills are being closely watched as the latest move in a high-stakes geopolitical chess match between the superpowers and their shared regional allies.

Some analysts see the drills as part of an incremental hardening of America’s military posture in the South China Sea under President Trump, a strategy that has not been accompanied by additional American diplomacy or incentives for its partners.

“The United States is taking a risk both that its partners will be less inclined to work with it because they are nervous about signaling security cooperation when there’s nothing else there, and that China will continue to advance in the places in which we are absent” on diplomatic and economic fronts, said Mira Rapp-Hooper, an expert on Asian security affairs at the Council on Foreign Relations in New York.

United States Navy sailors monitoring radar and other instruments aboard the guided-missile cruiser U.S.S. Chancellorsville in the South China Sea in 2016.

“So from a basic balance-of-power perspective, we are not holding the line nearly as well as we should be,” she added.

The United States Navy declined to comment on the record ahead of the drills, citing operational sensitivities.

But in a statement late Sunday, the Navy said the drills would include “a sea phase in international waters in Southeast Asia, including the Gulf of Thailand and South China Sea.”

It said they would focus partly on “search and seizure,” “maritime asset tracking” and “countering maritime threats,” among other subjects.

The statement said the drills would include eight warships, four aircraft and more than 1,000 personnel.

The statement said the drills would include eight warships, four aircraft and more than 1,000 personnel.

It said the American military hardware included a littoral combat ship, a guided-missile destroyer, three MH-60 helicopters and a P-8 Poseidon plane.

The Poseidon is a type of reconnaissance aircraft that the United States has used to conduct surveillance flights over the South China Sea, including around disputed reefs that China has filled out and turned into military bases.

The drills were scheduled to begin on Monday at Sattahip, a Thai naval base, after “pre-sail activities in Thailand, Singapore and Brunei,” and to end in Singapore.

The Poseidon is a type of reconnaissance aircraft that the United States has used to conduct surveillance flights over the South China Sea, including around disputed reefs that China has filled out and turned into military bases.

The drills were scheduled to begin on Monday at Sattahip, a Thai naval base, after “pre-sail activities in Thailand, Singapore and Brunei,” and to end in Singapore.

The Navy’s statement did not say when the drills would end.

Many of the drills will take place this week off Ca Mau Province, on the southern tip of Vietnam, said Thitinan Pongsudhirak, a Thai political analyst.

Many of the drills will take place this week off Ca Mau Province, on the southern tip of Vietnam, said Thitinan Pongsudhirak, a Thai political analyst.

He added that the drills would “reinforce the view that geopolitical tensions are shifting from land to sea.”

An MH-60 helicopter preparing for to take off from the U.S.S. Chancellorsville in the South China Sea in 2016.

The timing is ideal for Vietnam, which is deeply worried about a state-owned Chinese survey ship that has been spotted this summer in what the Vietnamese regard as their own territorial waters.

An MH-60 helicopter preparing for to take off from the U.S.S. Chancellorsville in the South China Sea in 2016.

The timing is ideal for Vietnam, which is deeply worried about a state-owned Chinese survey ship that has been spotted this summer in what the Vietnamese regard as their own territorial waters.

Last month, the State Department called the survey ship’s movements an effort by Beijing to “intimidate other claimants out of developing resources in the South China Sea,” including what it said was $2.5 trillion worth of unexploited oil and natural gas.

“Vietnam should be happy” that the drills are taking place given China’s recent “aggression in its waters,” said Luc Anh Tuan, a researcher at the University of New South Wales in Australia.

“Hanoi nevertheless will manage to downplay the significance of the drill because like other ASEAN fellows, it does not want to create an impression of a coalition against China,” added Tuan, who is on educational leave from the Vietnamese Ministry of Public Security.

“Vietnam should be happy” that the drills are taking place given China’s recent “aggression in its waters,” said Luc Anh Tuan, a researcher at the University of New South Wales in Australia.

“Hanoi nevertheless will manage to downplay the significance of the drill because like other ASEAN fellows, it does not want to create an impression of a coalition against China,” added Tuan, who is on educational leave from the Vietnamese Ministry of Public Security.

The Vietnamese Foreign Ministry confirmed in an email last week that the drills were happening, but declined to answer other questions.

Beijing’s actions in the sea are hugely sensitive for Hanoi because it is under heavy domestic pressure to be tough on China, its largest trading partner and former colonial occupier.

Beijing’s actions in the sea are hugely sensitive for Hanoi because it is under heavy domestic pressure to be tough on China, its largest trading partner and former colonial occupier.

But Vietnam is also racing to find new energy sources to power its fast-growing economy.

In a sign of those tensions, there were rare anti-Chinese riots in Vietnam in 2014, after a state-owned Chinese company defiantly towed an oil rig into disputed waters near the Vietnamese coast, prompting a tense maritime standoff.

In a sign of those tensions, there were rare anti-Chinese riots in Vietnam in 2014, after a state-owned Chinese company defiantly towed an oil rig into disputed waters near the Vietnamese coast, prompting a tense maritime standoff.

Three years later, Vietnam suspended a gas-drilling project in the sea by a subsidiary of a Spanish company because the project was said to have irritated Beijing.

The Chancellorsville in the South China Sea in 2016, with a Chinese Navy frigate in the background.

ASEAN countries will be more concerned about China’s reaction to the drills than they were about the American reaction to last year’s drills with China, said Gregory B. Poling, an expert on Southeast Asia at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

He said that was especially true for countries, such as Thailand, that had no territorial disputes in the sea with China.

“They don’t want to do it in a way that upsets the apple cart” of trade with China, he said of the Thai authorities.

“They don’t want to do it in a way that upsets the apple cart” of trade with China, he said of the Thai authorities.

The Thai Navy declined to comment.

The United States Navy said in its statement that its joint naval drills with ASEAN were first proposed in 2017 and confirmed last October.

The United States Navy said in its statement that its joint naval drills with ASEAN were first proposed in 2017 and confirmed last October.

That is the same month that China held its first joint naval drills with ASEAN, off its southern coast.

In a telephone interview, Kasit Piromya, a former Thai foreign minister, downplayed the risks for ASEAN of holding naval drills with the United States.

In a telephone interview, Kasit Piromya, a former Thai foreign minister, downplayed the risks for ASEAN of holding naval drills with the United States.

“From Thailand’s point of view, it’s still an open sea,” he said, adding that any such exercises with any outside partner should be neither aggressive nor defensive.

But Beijing’s territorial claims in the sea have no legal basis, he added, echoing the conclusion of an international tribunal that ruled against China three years ago.

But Beijing’s territorial claims in the sea have no legal basis, he added, echoing the conclusion of an international tribunal that ruled against China three years ago.

He said a key question now was whether Southeast Asian leaders could summon the “guts” to confront China’s construction of artificial islands and military bases in the sea, even though some of them have been “kowtowing to Chinese pressures and financial generosity.”

“I would urge the ASEAN leaders, the 10 of them, to get together and speak in a black-and-white manner to the Chinese leadership without being blackmailed or bought out by China’s financial offers,” he said.

“I would urge the ASEAN leaders, the 10 of them, to get together and speak in a black-and-white manner to the Chinese leadership without being blackmailed or bought out by China’s financial offers,” he said.

Chinese survey vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8 conducts research on behalf of the Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey in this photo shared July 25, 2018. The ship once again entered what Vietnam's exclusive economic zone near Vanguard Bank of South China Sea's Spratly Islands on August 13 of this year.

Chinese survey vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8 conducts research on behalf of the Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey in this photo shared July 25, 2018. The ship once again entered what Vietnam's exclusive economic zone near Vanguard Bank of South China Sea's Spratly Islands on August 13 of this year.

Mike Pence: 'Empire and aggression have no place in the Indo-Pacific'

Mike Pence: 'Empire and aggression have no place in the Indo-Pacific'