By CHRIS HORTON

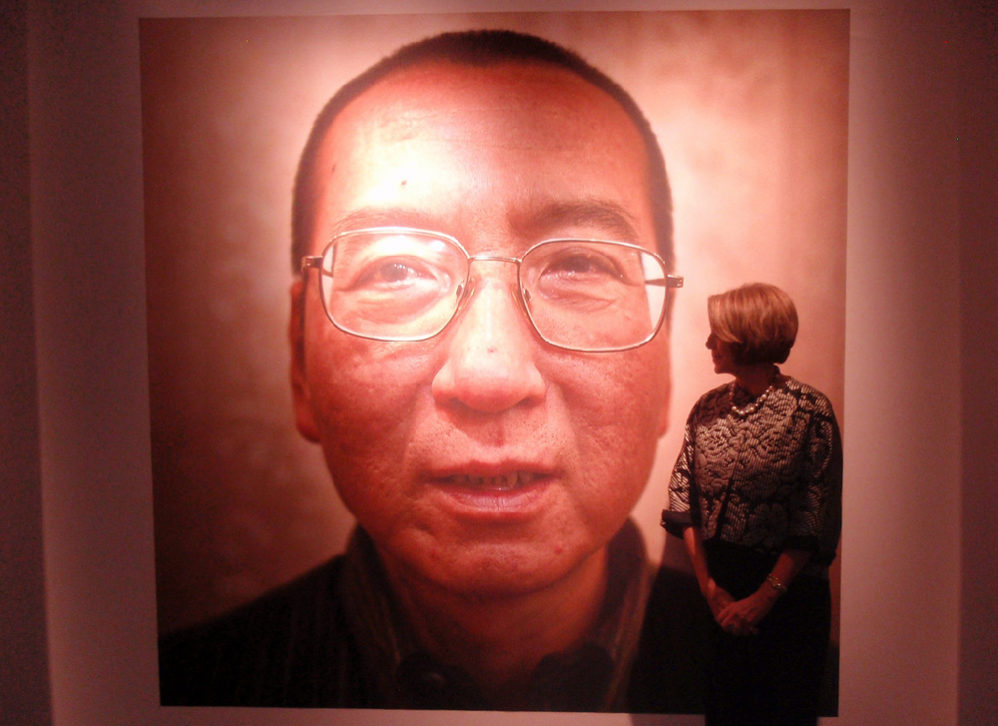

Pictures of Lee Ming-cheh, left, a rights advocate from Taiwan, and Tashi Wangchuk, an education advocate from Tibet, during a commemoration last month in Taiwan of the 1989 pro-democracy crackdown in China. Both men are in Chinese custody.

TAIPEI, Taiwan — For many in Taiwan, the death in custody last week of the Chinese Nobel Peace laureate Liu Xiaobo had double relevance.

It was a reminder of how much Taiwan — but not China — has changed politically since the late 1980s, when both were one-party, authoritarian states.

On Saturday, Taiwan, now a full-fledged democracy, celebrated the 30th anniversary of the end of four decades of martial law.

On Tuesday, at the opening of the first Asian bureau of Reporters Without Borders, an organization that advocates press freedom, Wu’er Kaixi, a leader of the 1989 pro-democracy demonstrations in Beijing, dedicated a moment of silence to Mr. Liu, while praising Taiwan’s progress.

But the death of Mr. Liu, who was serving an 11-year prison sentence for his role in Charter 08, a manifesto for peaceful political change, also deepened concerns over the fate of Lee Ming-cheh, a human rights advocate from Taiwan who went missing after his arrival in the southern Chinese province of Guangdong in March.

More than a week passed before Chinese officials announced that Mr. Lee had been detained.

But the death of Mr. Liu, who was serving an 11-year prison sentence for his role in Charter 08, a manifesto for peaceful political change, also deepened concerns over the fate of Lee Ming-cheh, a human rights advocate from Taiwan who went missing after his arrival in the southern Chinese province of Guangdong in March.

More than a week passed before Chinese officials announced that Mr. Lee had been detained.

In April, Mr. Lee’s wife, Lee Ching-yu, was blocked from entering China, where she said she hoped to take him his blood-pressure medication.

In late May, Mr. Lee was officially arrested on a charge of “subverting state power.”

It has not been lost on Mr. Lee’s family and friends, or the news media in Taiwan, that the charge he faces is similar to the one brought against Mr. Liu, of “inciting subversion of state power.”

Hours after Mr. Liu’s death, Taiwan’s state-owned Central News Agency reported that the governing Democratic Progressive Party had issued a statement calling on China to release Mr. Liu’s widow, Liu Xia, who was placed under house arrest in 2010, as well as Mr. Lee.

Comparing the plights of Mr. Liu and Mr. Lee, a commentary this month in a Taiwan newspaper, Liberty Times, asked: “Will Lee Ming-cheh be the next Liu Xiaobo?”

“What’s similar is that Lee Ming-cheh and Liu Xiaobo were both arrested for the crime of ‘subversion of state power,’” it said.

Comparing the plights of Mr. Liu and Mr. Lee, a commentary this month in a Taiwan newspaper, Liberty Times, asked: “Will Lee Ming-cheh be the next Liu Xiaobo?”

“What’s similar is that Lee Ming-cheh and Liu Xiaobo were both arrested for the crime of ‘subversion of state power,’” it said.

“What’s different is that Liu Xiaobo is Chinese, whereas Lee Ming-cheh is Taiwanese. After Lee Ming-cheh entered prison, will he ‘get sick’ or be forcefully ‘sickened’? This deserves attention.”

Nongovernmental organization workers from Taiwan who travel to China should remain on a high state of alert, the commentary added.

Nongovernmental organization workers from Taiwan who travel to China should remain on a high state of alert, the commentary added.

“You absolutely do not want to become the next Lee Ming-cheh,” it said.

In a letter to The Washington Post published on Sunday, Stanley Kao, Taiwan’s envoy to the United States, also connected the cases.

“Mr. Liu’s lifelong beliefs are the core values we live by in Taiwan, namely an abiding respect for human rights and due process of law,” Mr. Kao wrote, adding that China should immediately release Mr. Lee.

Beijing severed official communication channels with Taiwan in the fall after it became apparent that President Tsai Ing-wen, who took office in May last year, would not bow to Chinese pressure to endorse the “1992 consensus,” which holds that China and Taiwan agree there is “one China” — with each side reserving its own interpretation of what that means.

In a letter to The Washington Post published on Sunday, Stanley Kao, Taiwan’s envoy to the United States, also connected the cases.

“Mr. Liu’s lifelong beliefs are the core values we live by in Taiwan, namely an abiding respect for human rights and due process of law,” Mr. Kao wrote, adding that China should immediately release Mr. Lee.

Beijing severed official communication channels with Taiwan in the fall after it became apparent that President Tsai Ing-wen, who took office in May last year, would not bow to Chinese pressure to endorse the “1992 consensus,” which holds that China and Taiwan agree there is “one China” — with each side reserving its own interpretation of what that means.

Beijing has insisted that self-ruled Taiwan is part of its territory, and it has not renounced the use of force to achieve unification.

That has left the Tsai administration with limited tools to press Beijing for information about Mr. Lee. Ms. Tsai — one of the first government leaders to issue a statement mourning Mr. Liu’s death — has taken to her Twitter account to call for Mr. Lee’s release.

If history is any guide, progress on Mr. Lee’s case is unlikely in the coming weeks.

That has left the Tsai administration with limited tools to press Beijing for information about Mr. Lee. Ms. Tsai — one of the first government leaders to issue a statement mourning Mr. Liu’s death — has taken to her Twitter account to call for Mr. Lee’s release.

If history is any guide, progress on Mr. Lee’s case is unlikely in the coming weeks.

The Chinese Communist Party is preparing for its 19th Party Congress this fall, a meeting that will determine the leadership lineup under Xi Jinping for the next five years and influence the succession beyond that.

In the jockeying for power, concessions to Taiwan could be interpreted as a sign of weakness.

Eeling Chiu, secretary general of the Taiwan Association for Human Rights, has supported Ms. Lee’s efforts to rally international pressure on China to free her husband.

Eeling Chiu, secretary general of the Taiwan Association for Human Rights, has supported Ms. Lee’s efforts to rally international pressure on China to free her husband.

Ms. Chiu said that there had been no information about Mr. Lee’s situation aside from occasional statements from Beijing, such as the announcement last month that a lawyer had been appointed to represent him.

“We haven’t heard anything new since they announced they’d appointed him a lawyer,” she said in an interview, dismissing the gesture as “fake.”

“We haven’t heard anything new since they announced they’d appointed him a lawyer,” she said in an interview, dismissing the gesture as “fake.”

“We don’t even know who the lawyer is. If you’re trying to provide for the rights of someone involved in legal proceedings, getting in touch with their family is one of the most basic things you should do.”

The Tsai administration says it will continue to work on Mr. Lee’s behalf.

The Tsai administration says it will continue to work on Mr. Lee’s behalf.

“The government is doing everything it can to secure Mr. Lee’s release as soon as possible,” Alex Huang, the spokesman for the presidential office, said on Tuesday.