By Hannah Beech

An American crew monitored China’s buildup in the South China Sea this month from a Navy P-8A Poseidon reconnaissance plane.

An American crew monitored China’s buildup in the South China Sea this month from a Navy P-8A Poseidon reconnaissance plane.

NEAR MISCHIEF REEF, South China Sea — As the United States Navy reconnaissance plane banked low near Mischief Reef in the South China Sea early this month, a Chinese warning crackled on the radio.

“U.S. military aircraft,” came the challenge, delivered in English in a harsh staccato.

“You have violated our China sovereignty and infringed on our security and our rights. You need to leave immediately and keep far out.”

Aboard the P-8A Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft, flying in what is widely considered to be international airspace, Lt.

Dyanna Coughlin scanned a live camera feed showing the dramatic evolution of Mischief Reef.

Five years ago, this was mostly an arc of underwater atoll populated by tropical fish and turtles.

Now Mischief Reef, which is off the Philippine coast but controlled by China, has been filled out and turned into a Chinese military base, complete with radar domes, shelters for surface-to-air missiles and a runway long enough for fighter jets.

Six other nearby shoals have been similarly transformed by Chinese dredging.

“I mean, this is insane,” Lieutenant Coughlin said.

“Look at all that crazy construction.”

A rare visit on board a United States Navy surveillance flight over the South China Sea pointed out how profoundly China has reshaped the security landscape across the region.

The country’s aggressive territorial claims and island militarization have put neighboring countries and the United States on the defensive, even as President Trump’s administration is stepping up efforts to highlight China’s controversial island-building campaign.

In congressional testimony before assuming his new post as head of the United States Indo-Pacific Command in May, Adm.

Philip S. Davidson sounded a stark warning about Beijing’s power play in a sea through which roughly one-third of global maritime trade flows.

“In short, China is now capable of controlling the South China Sea in all scenarios short of war with the United States,” Admiral Davidson said, an assessment that caused some consternation in the Pentagon.

A view of Subi Reef and the array of vessels there.

A view of Subi Reef and the array of vessels there.

How Beijing relates to its neighbors in the South China Sea could be a harbinger of its interactions elsewhere in the world.

Xi Jinping has held up the island-building effort as a prime example of “China moving closer to center stage” and standing “tall and firm in the East.”

In a June meeting with Defense Secretary

Jim Mattis, Xi vowed that China “cannot lose even one inch of the territory” in the South China Sea, even though an international tribunal has dismissed Beijing’s expansive claims to the waterway.

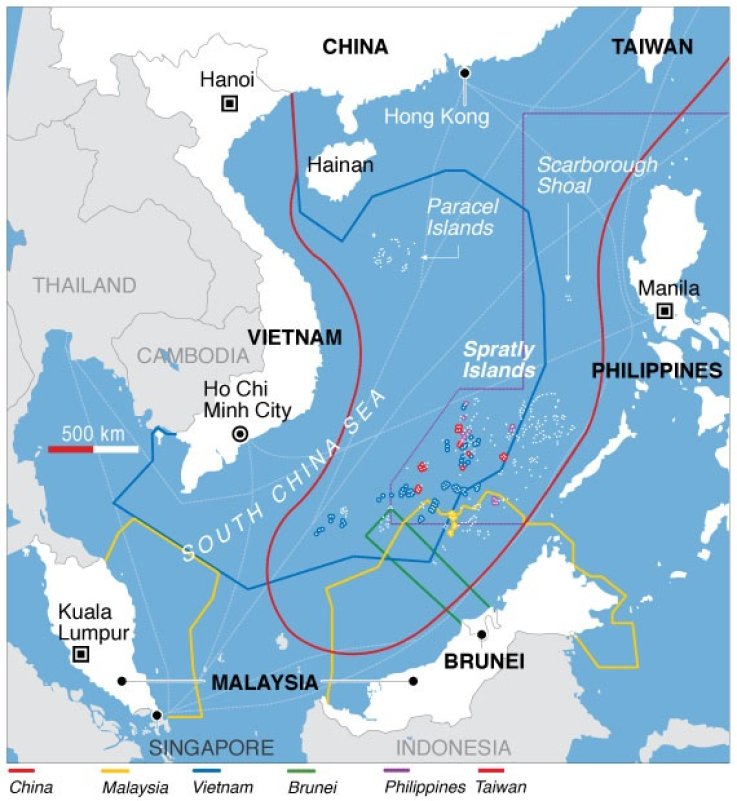

The reality is that governments with overlapping territorial claims — representing Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei — lack the firepower to challenge China.

The United States has long fashioned itself as a keeper of peace in the Western Pacific.

But it’s a risky proposition to provoke conflict over a scattering of rocks in the South China Sea, analysts say.

“As China’s military power grows relative to the United States, and it will, questions will also grow regarding America’s ability to deter Beijing’s use of force in settling its unresolved territorial issues,” said Rear Adm.

Michael McDevitt, who is now a senior fellow in strategic studies at the Center for Naval Analyses.

An unexpected encounter in the South China Sea could also set off an international incident.

A 1.4-million-square-mile sea presents a kaleidoscope of shifting variables: hundreds of disputed shoals, thousands of fishing boats, coast guard vessels and warships and, increasingly, a collection of Chinese fortresses.

In late August, one of the Philippines’ largest warships, a cast-off cutter from the United States Coast Guard, ran aground on Half Moon Shoal, an unoccupied maritime feature not far from Mischief Reef.

The Chinese, who also claim the shoal, sent vessels from nearby artificial islands, but the Philippines refused any help.

After all, in 2012, the Chinese Coast Guard had muscled the Philippines off of Scarborough Shoal, a reef just 120 nautical miles from the main Philippine island of Luzon.

Another incident in 1995 brought a Chinese flag to Mischief Reef, also well within what international maritime law considers a zone where the Philippines has sovereign rights.

Could somewhere like Half Moon Shoal be the next flash point in the South China Sea?

“A crisis at Half Moon was averted, but it has always been the risk with the South China Sea that a small incident in remote waters escalates into a much larger crisis through miscommunication or mishandling,” said

Ian Storey, a senior fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore. “That’s why this is all so dangerous. It’s not just a pile of rocks that can be ignored.”

Monitoring feeds from a camera controlled by an observer, front left, on the naval reconnaissance mission early this month.

‘Leave immediately!’

Monitoring feeds from a camera controlled by an observer, front left, on the naval reconnaissance mission early this month.

‘Leave immediately!’

On the scratchy radio channel, the Chinese challenges kept on coming.

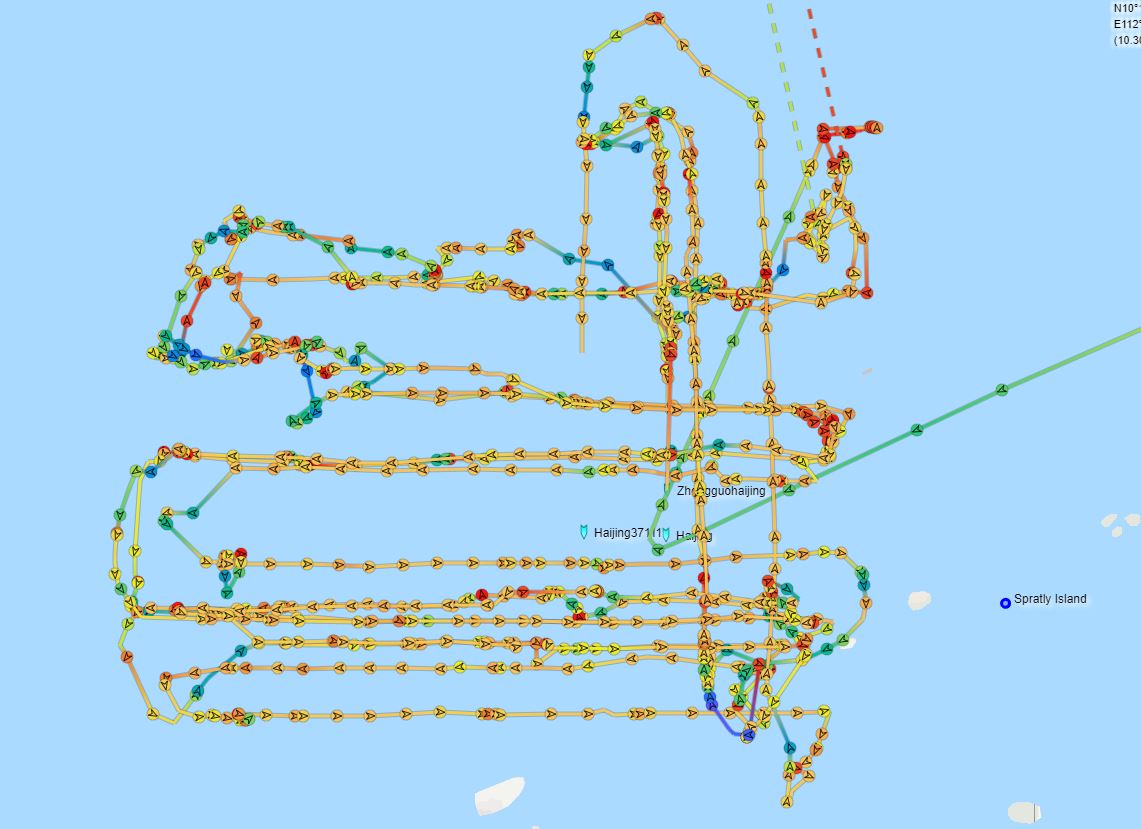

Eight separate times during the mission this month, Chinese dispatchers queried the P-8A Poseidon. Twice, the Chinese accused the American military aircraft not just of veering close to what Beijing considered its airspace but also of violating its sovereignty.

“Leave immediately!” the Chinese warned over and over.

Cmdr.

Chris Purcell, the American squadron commander, said such challenges have been routine during the four months he has flown missions over the South China Sea.

“What they want is for us to leave, and then they can say that we left because this is their sovereign territory,” he said.

“It’s kind of their way to try to legitimize their claims, but we are clear that we are operating in international airspace and are not doing anything different from what we’ve done for decades.”

In 2015, Xi Jinping stood in the Rose Garden at the White House and promised that “there is no intention to militarize” a collection of disputed reefs in the South China Sea known as the Spratlys.

But since then, Chinese dredgers have poured mountains of sand onto Mischief Reef and six other Chinese-controlled features in the Spratlys.

China has added at least 3,200 acres of new land in the area, according to the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative run by the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Descending as low as 5,000 feet, the surveillance flight this month gave a bird’s-eye view of the Chinese construction.

On Subi Reef, a construction crane swung into action next to a shelter designed for surface-to-air missiles.

There were barracks, bunkers and open hangars.

At least 70 vessels, some warships, surrounded the island.

On Fiery Cross Reef, a complex of buildings with Chinese eaves was arrayed at the center of the reclaimed island, including an exhibition-style hall with an undulating roof.

It looked like a typical newly built town in interior China — except for the radar domes that protruded like giant golf balls across the reef.

A military-grade runway ran the length of the island, and army vehicles trundled across the tarmac. Antenna farms bristled.

“It’s impressive to see the Chinese building, given that this is the middle of the South China Sea and far away from anywhere, but the idea that this isn’t militarized, that’s clearly not the case,” Commander Purcell said.

“It’s not hidden or anything. The intention, it’s there plain to see.”

In other spots, reclamation could also be seen on Vietnamese-controlled features, such as West London Reef, where workers dragged equipment past piles of sand.

But dredging by Southeast Asian nations is scant compared with the Chinese effort.

In April, China for the first time deployed antiship and antiaircraft missiles on Mischief, Subi and Fiery Cross, American military officials said.

The following month, a long-range bomber landed on Woody Island, another contested South China Sea islet.

A Pentagon report released in August said that with forward operating bases on artificial islands in the South China Sea,

the People’s Liberation Army was honing its “capability to strike U.S. and allied forces and military bases in the western Pacific Ocean, including Guam.”

In response to the intensifying militarization of the South China Sea, the United States in May disinvited China from joining the biannual Rim of the Pacific naval exercise, the world’s largest maritime warfare training, involving more than 20 navies.

“We are prepared to support China’s choices, if they promote long-term peace and prosperity,” Mr. Mattis said, explaining the snub.

“Yet China’s policy in the South China Sea stands in stark contrast to the openness of our strategy.”

Radar towers, hangars and five-story buildings seen on Fiery Cross Reef.

Projecting Power

Radar towers, hangars and five-story buildings seen on Fiery Cross Reef.

Projecting Power

For its part, Beijing claims the United States is the one militarizing the South China Sea.

In addition to the routine surveillance flyovers, President Trump has sent American warships more frequently to waters near China’s man-made islands.

These freedom of navigation patrols, which occur worldwide, are meant to show the United States’ commitment to maritime free passage, Pentagon officials say.

The last such operation by the United States was in May, when two American warships sailed near the Paracels, another contested South China Sea archipelago.

Beijing was irate.

The United States says that it does not take any side in territorial disputes in the South China Sea.

On its maps, China uses a so-called nine-dash line to scoop out most of the waterway’s turf as its own.

But international legal precedent is not on China’s side when it comes to the dashed demarcation, a version of which was first used in the 1940s.

In 2016, an international tribunal dismissed Beijing’s nine-dash claim, judging that China has no historical rights to the South China Sea.

The case was brought by the Philippines after Scarborough Shoal was commandeered by China in 2012, following a tense blockade.

The landmark ruling, however, has had no practical effect.

That’s in large part because

Rodrigo Duterte, who became president of the Philippines less than a month before the tribunal reached its decision, chose not to press the matter with Beijing.

He declared China his new best friend and dismissed the United States as a has-been power.

But last month, Mr. Duterte took Beijing to task when a recording aired on the BBC from another P-8A Poseidon mission over the South China Sea demonstrated that

Chinese dispatchers were taking a far more aggressive tone with Philippine aircraft than with American ones.

“I hope China would temper its behavior,” Mr. Duterte said.

“You cannot create an island and say the air above it is yours.”

The crew disembarking on Okinawa, Japan, after their mission over the South China Sea.

Missed Opportunities

The crew disembarking on Okinawa, Japan, after their mission over the South China Sea.

Missed Opportunities

Perceptions of power — and Chinese reactions to these projections — have led analysts to criticize

Barack Obama as having been too timid in countering China over what Adm.

Harry B. Harris Jr., the former head of the United States Pacific Command, memorably called a “great wall of sand” in the South China Sea.

Critics, for instance, have faulted the previous administration for not conducting more frequent freedom of navigation patrols.

“China’s militarization of the South China Sea has been a gradual process, with several phases where alternative actions by the U.S., as well as other countries, could have changed the course of history,” said

Alexander Vuving, a professor at the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies in Honolulu.

Chief among these moments, Mr. Vuving said, was China’s takeover of Scarborough Shoal.

The United States declined to back up the Philippines, a defense treaty ally, by sending Coast Guard vessels or warships to an area that international law has designated as within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone.

“Seeing U.S. commitment to its ally, Beijing might not have been as confident as it was with its island-building program,” Mr. Vuving said.

“The U.S. failure to support its ally in the Scarborough standoff also demonstrated to people like Duterte that he had no other option than to kowtow to China.”

With most of the Spratly military bases nearing completion by the end of the year, according to Pentagon assessments, the next question is whether — or more likely when — China will begin building on Scarborough.

A Chinese base there would put the People’s Liberation Army in easy striking distance of the Philippine capital, Manila.

From the American reconnaissance plane, Scarborough looked like a perfect diving retreat, a lazy triangle of reef sheltering turquoise waters.

But Chinese Coast Guard vessels could be seen circling the shoal, and Philippine fishermen have complained about being prevented from accessing their traditional waters.

“Do you see any construction vessels around there?” Lieutenant Coughlin asked.

“Negative, ma’am,” replied Lt. Joshua Grant, as he used a control stick to position the plane’s camera over Scarborough Shoal.

“We’ll see if it changes next time.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/62719257/1024819516.jpg.0.jpg)

Chinese survey vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8 conducts research on behalf of the Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey in this photo shared July 25, 2018. The ship once again entered what Vietnam's exclusive economic zone near Vanguard Bank of South China Sea's Spratly Islands on August 13 of this year.

Chinese survey vessel Haiyang Dizhi 8 conducts research on behalf of the Guangzhou Marine Geological Survey in this photo shared July 25, 2018. The ship once again entered what Vietnam's exclusive economic zone near Vanguard Bank of South China Sea's Spratly Islands on August 13 of this year.

_demonstrates_small_craft_incursion_deterrence_by_using_their_forward_mounted_.50_caliber_machine_guns.jpg)

Monitoring feeds from a camera controlled by an observer, front left, on the naval reconnaissance mission early this month.

Monitoring feeds from a camera controlled by an observer, front left, on the naval reconnaissance mission early this month.

HMS Albion passed by the Paracel Islands in recent days to challenge Beijing's excessive claims

HMS Albion passed by the Paracel Islands in recent days to challenge Beijing's excessive claims