By CHRIS BUCKLEY and DIDI KIRSTEN TATLOW

In Beijing last year, the wives of human rights lawyers who were detained in 2015, from left, Wang Yanfang, Li Wenzu, Chen Guiqiu, Fan Lili, Liu Ermin, and Wang Qiaoling.

In Beijing last year, the wives of human rights lawyers who were detained in 2015, from left, Wang Yanfang, Li Wenzu, Chen Guiqiu, Fan Lili, Liu Ermin, and Wang Qiaoling.

BEIJING — Before her husband disappeared into detention, Chen Guiqiu did not ask him much about his risky work as a Chinese human rights lawyer.

Before word crept out that he had been tortured, Ms. Chen trusted the police.

Before she was told she could not leave

China, she never expected she would make a perilous escape abroad.

Ms. Chen and her two daughters reached the United States in March after an overland journey to Thailand that almost ended in their deportation back to China.

Her husband,

Xie Yang, was

tried and convicted this month of subversion and disrupting a court.

But Ms. Chen said her escape was the culmination of a personal transformation that began after

he was detained almost two years ago.

“It was because of all the pressure from all sides — from state security police, my employer — and slowly I lost commitment and hope,” Ms. Chen said in a telephone interview from her temporary home in Texas.

“I was always being followed. I felt I was living without freedom.”

Ms. Chen’s evolution was part of a startling outcome of China’s crackdown on outspoken rights lawyers and advocates that

began in July 2015 — the spouses who resisted.

She and other wives of rights advocates held in China described their experiences to a congressional

subcommittee in Washington on Thursday.

After their loved ones disappeared in the wave of arrests, some family members, especially the wives of the detained lawyers, overcame their fear and fought back, often in a theatrical fashion.

They gathered in bright red clothes and with

red buckets to publicize their demands for information and access to the prisoners.

Their tongue-in-cheek slogan became “Leave the dressing table and take on the thugs,” said

Li Wenzu, whose husband,

Wang Quanzhang, a human rights lawyer, has remained in secretive custody 21 months after

he was detained in August 2015.

“The story of the wives is one of the great stories of the whole crackdown — it is a brilliant adaptation by the activists to repression,” said

Terence Halliday, a researcher at the American Bar Foundation in Chicago who has written a book on Chinese criminal defense lawyers.

“My goodness, the attention they have brought to bear, not just for their husbands, but also the state of the crackdown.”

Chinese state investigators have long applied pressure on detainees’ families to win cooperation and confessions.

But this time their tactics seemed more systematic, said

Wang Qiaoling, the wife of a detained lawyer,

Li Heping.

Mr. Li was recently released after being tried and receiving a

suspended prison sentence.

“They can treat you like hand-pulled noodles, squeeze you into any shape,” Ms. Wang, 45, said in an interview.

“If you’re isolated and scared, it’s hard to resist.”

Some wives of detainees said they had been forced to move from rented apartments after the police warned landlords.

Some were prevented from enrolling their children in school.

And the police recruited relatives to beg them to stay quiet and compliant.

The families described these tactics as “lianzuo” or “zhulian,” old Chinese terms for the collective punishment of families.

Wang Qiaoling, the wife of the detained lawyer Li Heping, in Beijing last year. Mr. Li was recently released after receiving a suspended prison sentence.

Wang Qiaoling, the wife of the detained lawyer Li Heping, in Beijing last year. Mr. Li was recently released after receiving a suspended prison sentence.

Some families buckled.

But others protested and filed petitions about the secretive detentions and trials.

Ms. Wang encouraged a tight circle of women who rallied the relatives of detainees, arguing that silence would only encourage courts to hand down stiffer sentences.

“If you want to protect your family, you can’t stay silent,” Ms. Wang said.

“It’s been crucial that we’ve been able to stick together.”

But for Ms. Chen, 42, the journey to defiance was especially wrenching.

While many of the detained lawyers lived in Beijing, she lived in Changsha, the capital of Hunan Province, about 800 miles to the south.

And she had a secure, state-funded job as a

professor of environmental engineering at Hunan University, studying ways to remove heavy metal and organic pollution from water.

While Mr. Xie traveled relentlessly, she cared for their two daughters, now ages 4 and 15.

And when Mr. Xie was home, they barely discussed his contentious legal cases.

“It never occurred to me that he could get into serious trouble for being a lawyer,” she said.

“The children kept us busy enough.”

Initially, when the police took Mr. Xie away, Ms. Chen thought he would be freed quickly once investigators found that he had committed no crime.

She kept quiet, heeding the advice of the police that silence would buy him lenience.

“Under heavy pressure and ignorant, I chose to accept the police’s illegal orders and went along with them for nearly nine months,” she wrote last year in an

essay about her experiences.

“I heeded the advice of the state security: no media interviews, no going abroad, no contact with other families involved in the case.”

But like other family members, she ran up against an opaque legal system that held detainees in secrecy for many months with no visits by relatives or access to lawyers.

“Not one office followed the law, not one gave us a legal response,” she said in the interview.

“That was totally different from what I expected. This was a legal case, and I wanted to defend my husband by using the law, but it was impossible to use the law.”

Her growing frustration led her to speak up and contact other wives of detainees, including Ms. Wang, who offered advice and encouragement.

Ms. Chen was spared some of the intimidation that other families described.

Her children were not singled out at school, she said.

But other wives of detainees said their children had been denied access to schools or kindergartens in Beijing after officials warned principals or refused to process paperwork.

But Ms. Chen felt a shock in April last year when she tried to take her daughters on a trip to Hong Kong, a self-governed city that mainland Chinese must get a special pass to enter.

The police stopped her from taking the train across the border on the grounds that she was a security risk.

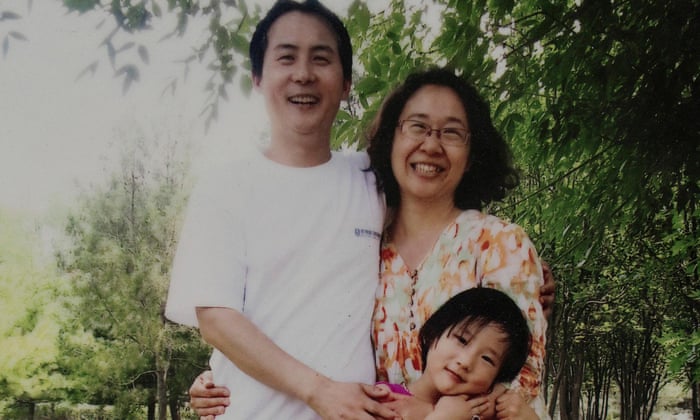

Chen Guiqiu, right, with her daughters after arriving at an airport in Texas in March.

Chen Guiqiu, right, with her daughters after arriving at an airport in Texas in March.

“I woke up to the fact that I was being treated as guilty by association,” she said.

“They told me I was deemed a threat to national security, and if I was already regarded as guilty, then Xie Yang was, too.”

In touch now with a circle of wives of detainees, she occasionally took part in their demands for access and information when she visited Beijing.

Partly inspired by feminist protests in China in 2015, they took to

carrying red buckets and displaying

red slogans on their dresses as a display of defiance, especially when visiting Tianjin, the port city near Beijing where many of their husbands were held.

“We developed a headstrong mentality,” Ms. Wang said.

“The more they wanted to make us feel like heinous criminals, the more we kept up a relaxed, casual attitude.”

But staying upbeat was not easy.

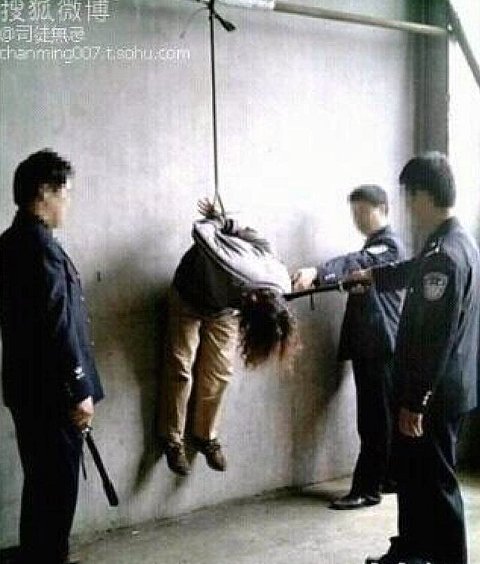

Ms. Chen began to hear that her husband had been tortured in Hunan, where he was held.

At first, the accounts came indirectly.

Then, when Mr. Xie was allowed to see his lawyers in January this year, he spilled out a

description of abuses, including

beatings and deprivation of sleep.

Ms. Chen decided to release the

transcripts online, hoping that the publicity would help end the abuses.

“

Let the world know what forced confession through torture is, what shamelessness without limit is,” Ms. Chen

said in a statement at the time.

The government has denied those claims of torture, and at his recent trial, Mr. Xie also retracted them and pleaded guilty, after his own lawyers were replaced by ones chosen by the authorities.

But many family members of detained lawyers say that the evidence points to widespread abuses, including the forced taking of drugs that made the detainees docile and submissive.

By February, Ms. Chen lived under stifling surveillance, she said.

Constantly monitored at home and work, and warned by the police, university officials and relatives not to speak out more about her husband, she

decided to escape.

She gathered up her daughters, confided her plan to the older one and told the younger one they were going on a trip.

The security officers who followed her had become used to her driving away to work each day, but Ms. Chen and her daughters quietly walked out, evading the watchers.

Ms. Chen declined to describe the details of how she and her children made the journey to Thailand, fearing that would endanger people who helped her.

She kept her cellphone turned off, but the Thai police tracked her to a safe house — she believes with help from Chinese security officers alerted to her disappearance.

After a court appearance, Ms. Chen and her children were taken to a detention center and told they would be sent back to China.

Officials from the United States Embassy in Bangkok stepped in and secured her release after haggling with the Thai authorities, she said.

On March 17, Ms. Chen and her children arrived in Houston, after a standoff with Chinese and Thai officials at Bangkok International Airport.

Mr. Xie was given a suspended prison sentence, but he remains cut off from normal contact, apparently under police guard outside Changsha, Ms. Chen said.

“I hope that one day Xie Yang can join us here,” she said.

“But we might have to wait a long time to see him. We’ve already waited a long time.”

.jpg)