By John Sudworth

A picture of Mr Li from 2012 and one taken after his release

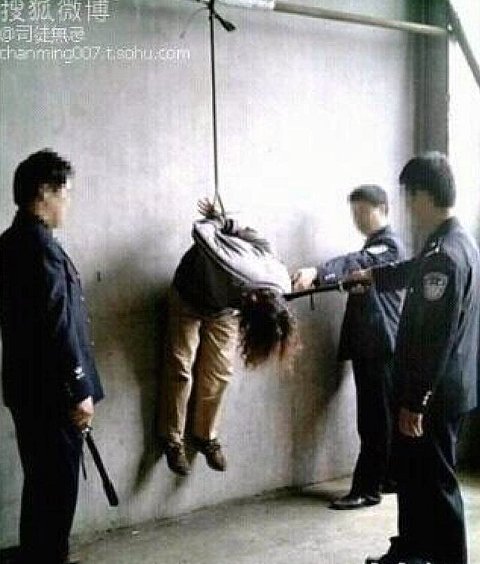

It's a form of restraint that would be more in keeping with the practices of a medieval dungeon than a modern, civilised state.

But the device -- leg and hand shackles linked by a short chain -- is a well-documented part of the toolkit that the Chinese police use to break the will of their detainees.

And it is one that they forced one of this country's most prominent human rights lawyers to wear, for a full month.

Li Heping was finally released from detention on Tuesday and his wife Wang Qiaoling has now had time to learn about the treatment he endured over his almost two-year-long incarceration.

"In May 2016 in the Tianjin Number One Detention Centre, he was put in handcuffs and shackles with an iron chain linking the two together," she tells me.

"It meant that he could not stand up straight, he could only stoop, even during sleeping. He wore that instrument of torture 24/7 for one month."

She adds: "They wanted him to confess."

China's war on law

In one sense, Mr Li was lucky.

A 2015 investigation by Human Rights Watch into the use of torture by the Chinese police revealed the case of a man who was forced to wear this type of device for eight years.

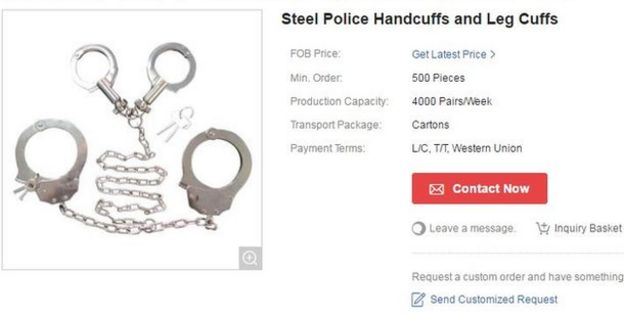

In 2014 an Amnesty International report documented the supply and manufacture of torture equipment by Chinese companies, including the combined hand and leg cuffs.

Torture devices like the one used on Li Heping are readily available online

"The use of these devices causes unnecessary discomfort and can easily result in injuries," William Nee, China Researcher at Amnesty International, tells me.

"Such devices place unwarranted restrictions on the movement of detainees and serve no legitimate law enforcement purpose that cannot be achieved by the use of handcuffs alone."

Li Heping is one of a group of human rights lawyers who were detained in July 2015, in a crackdown since referred to as China's war on law.

Of course, threats, intimidation and violence have always been part of the risks for any lawyer daring to take on the might of the Communist Party in its own courts.

But Xi Jinping has made it clear that he sees the ideal of constitutional rights, guaranteed by independent courts, as a threat to national security.

So his war on law sends a clear message.

"Such devices place unwarranted restrictions on the movement of detainees and serve no legitimate law enforcement purpose that cannot be achieved by the use of handcuffs alone."

Li Heping is one of a group of human rights lawyers who were detained in July 2015, in a crackdown since referred to as China's war on law.

Of course, threats, intimidation and violence have always been part of the risks for any lawyer daring to take on the might of the Communist Party in its own courts.

But Xi Jinping has made it clear that he sees the ideal of constitutional rights, guaranteed by independent courts, as a threat to national security.

So his war on law sends a clear message.

For those like Mr Li, representing the victims of China's illegal land grabs, religious persecution or political repression, the threat is not just from corrupt local officials or powerful businessmen, but from the state itself.

The before and after photos offer a visual clue to his time in detention.

One taken in 2012 shows an assured, cheery lawyer.

The one taken on his release shows him noticeably thinner and looking older than his years.

Wang Qiaoling tells me she barely recognised him.

And she tells me about the other forms of ill-treatment that her husband has described to her since his release.

"He was forced to take medicine. They stuffed the pills into his mouth as he refused to take them voluntarily," she says.

"The police told him that they were for high blood pressure, but my husband doesn't suffer from that.

"After taking the pills he felt pain in his muscles and his vision was blurred."

One taken in 2012 shows an assured, cheery lawyer.

The one taken on his release shows him noticeably thinner and looking older than his years.

Wang Qiaoling tells me she barely recognised him.

And she tells me about the other forms of ill-treatment that her husband has described to her since his release.

"He was forced to take medicine. They stuffed the pills into his mouth as he refused to take them voluntarily," she says.

"The police told him that they were for high blood pressure, but my husband doesn't suffer from that.

"After taking the pills he felt pain in his muscles and his vision was blurred."

Gruelling questioning

"He was beaten. He endured gruelling questioning while being denied sleep for days on end," she goes on.

"And he was forced to stand to attention for 15 hours a day, without moving."

Amnesty International's William Nee tells me that each of these methods of ill-treatment could be considered torture by themselves.

"Cumulatively, they would demonstrate a clear intent by the authorities to inflict physical and mental torture with the goal of getting Li Heping to confess," he says.

"Since China is a party to the Convention against Torture, these serious allegations should prompt the Chinese authorities to immediately launch a prompt, effective and impartial investigation to assess whether this torture took place."

Despite the prolonged and extreme nature of the torture, Ms Wang tells me her husband never did confess.

"He was worried that he might be tortured to death in the detention centre and he wouldn't make it to meet his family again, so he reached an agreement with the authorities that the trial would be held in secret.

"He would be given a suspended sentence but he never admitted guilt or confessed that he had subverted state power."

"Cumulatively, they would demonstrate a clear intent by the authorities to inflict physical and mental torture with the goal of getting Li Heping to confess," he says.

"Since China is a party to the Convention against Torture, these serious allegations should prompt the Chinese authorities to immediately launch a prompt, effective and impartial investigation to assess whether this torture took place."

Despite the prolonged and extreme nature of the torture, Ms Wang tells me her husband never did confess.

"He was worried that he might be tortured to death in the detention centre and he wouldn't make it to meet his family again, so he reached an agreement with the authorities that the trial would be held in secret.

"He would be given a suspended sentence but he never admitted guilt or confessed that he had subverted state power."

Barred from the media

At that secret trial, the details of which were released by China's state-controlled media afterwards, the court ruled that Mr Li had "repeatedly used the internet and foreign media interviews to discredit and attack state power and the legal system".

As a result of his conviction, he is now unable to practise law and has also signed an agreement that he will not carry out any further media interviews.

But his wife, despite constant intimidation, refuses to be similarly constrained.

Plain-clothes policemen still surround the family home and she was followed to our agreed interview location.

Wang Qiaoling's account tallies with that of other lawyers caught up in the crackdown, including Xie Yang, whose court case was heard this week.

He had alleged similar abuses during his interrogations -- including shackling, beatings and being made to remain in the same position for hours on end.

We called the Tianjin Number One detention centre to ask about the allegations that Li Heping was tortured there.

"We don't do any interviews," came the reply.

"If you want to do an interview, please go through the legal and proper channels."

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire