By Joshua Emerson Smith

A boat full of totoaba and its crew took the illegal catch to shore while being photographed with a Sea Shepherd drone.

An hourlong flight east of Hong Kong in the Chinese port city of Shantou, traders cater to affluent businessmen quietly looking to drop up to $30,000 dollars on a single fish bladder.

While these transactions are punishable by large fines and even time behind bars, a covert investigation by a nonprofit advocacy group has found that weak, corrupt, law enforcement allows fishermen, import-export companies and perhaps drug cartels to profit in an international supply chain that stretches from Asia back to Southern California and Mexico.

Chinese culture has believed for centuries that the organ — known locally as gold coin fish maw — has lifesaving properties.

While science has yet to prove the health benefits, the dried bladder is often kept for emergencies — for use as part of a medicinal soup.

It’s also gifted and displayed in homes as a status symbol.

“In Shantou, gold coin fish maw is usually treated as the priceless treasure of a shop, so they are not labeled a price and not on sale (openly),” a local trader in March told an undercover investigator with the Los Angeles-based Elephant Action League, a recently established organization that gathers intelligence on wildlife crimes.

This week, the nonprofit issued its report exposing the illegal fish-bladder trade in China and its consequences thousands of miles away.

“In Shantou, gold coin fish maw is usually treated as the priceless treasure of a shop, so they are not labeled a price and not on sale (openly),” a local trader in March told an undercover investigator with the Los Angeles-based Elephant Action League, a recently established organization that gathers intelligence on wildlife crimes.

This week, the nonprofit issued its report exposing the illegal fish-bladder trade in China and its consequences thousands of miles away.

The league said it intends to expand its watchdog work on this issue in the coming months.By the mid-20th century, Chinese demand for certain fish bladders had eviscerated stocks of the giant yellow croaker, which once thrived off China’s coast.

If a person is lucky enough to catch one of these rare fish today, it can fetch as much as half a million dollars on the black market.

Enthusiasm for fish bladders went unnoticed for decades by many in the West.

However, in recent years that has changed as desire for the illicit product has led to the near extinction of the vaquita porpoise, which lives in Baja California and is the most endangered marine mammal on the planet.

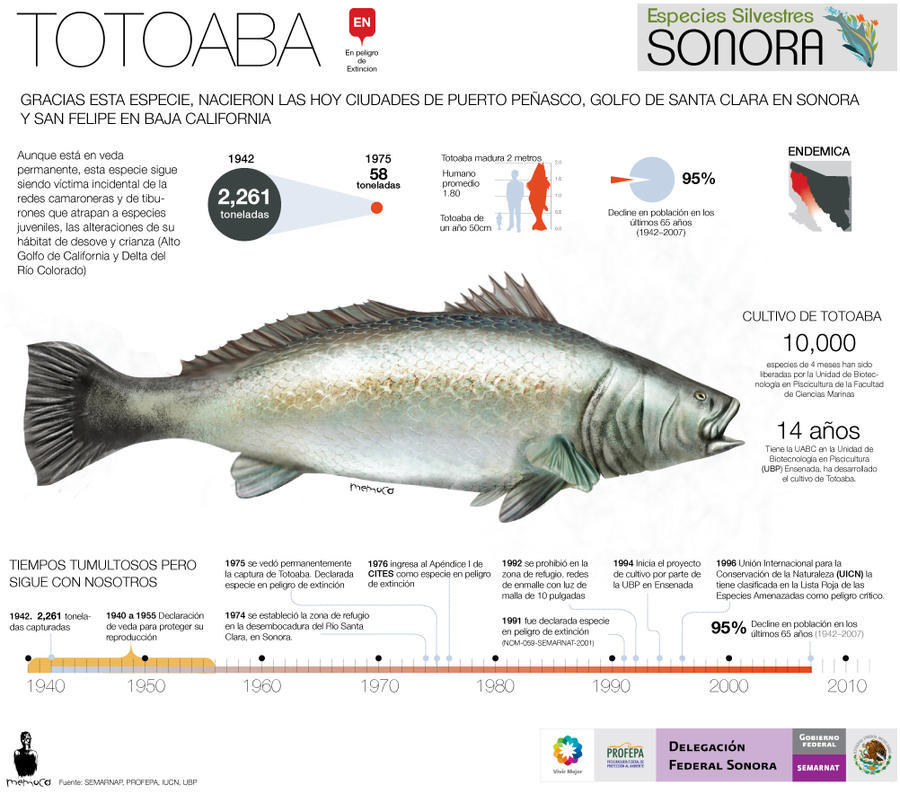

The totoaba, a 120-pound fish found in the Upper Gulf of Mexico, has a bladder that resembles that of the croaker’s — making it a prime target of poaching.

It’s suspected that drug cartels pay local fishermen in the region to catch the fish and deliver the prized organ.

While the six-foot-long totoabas are then dumped back into the sea, their dried bladders are shipped to Asia.

While the six-foot-long totoabas are then dumped back into the sea, their dried bladders are shipped to Asia.

At retail pricing, each bladder can fetch from $6,700 to more than $30,000 depending on its weight and other characteristics.

A gold coin fish maw at a store in the Chinese port city of Shantou.

A gold coin fish maw at a store in the Chinese port city of Shantou.

In the process, the nylon gillnets used to catch totoabas in the murky waters off of the fishing village of San Felipe in Baja California also ensnare and suffocate a number of other wildlife species, including whales, sharks, sea turtles, dolphins, rays — and those imperiled vaquitas.

Scientists with international conservation groups estimate that fewer than 30 vaquitas remain today, down from about 567 two decades ago.

The totoaba is also considered by international treaty to be endangered.

It’s unknown exactly how many are left.

The Elephant Action League’s undercover team, which includes retired law-enforcement officers from around the globe, visited more than two dozen shops in Shantou, China and the surrounding region in March.

The Elephant Action League’s undercover team, which includes retired law-enforcement officers from around the globe, visited more than two dozen shops in Shantou, China and the surrounding region in March.

The area is believed to be a main trading hub for the bladders.

“They pretend to be buyers or traders,” said Andrea Crosta, executive director and co-founder of the league, which employs a handful of full-time staff members and a network of about a couple dozen contractors around the world.

“They pretend to be buyers or traders,” said Andrea Crosta, executive director and co-founder of the league, which employs a handful of full-time staff members and a network of about a couple dozen contractors around the world.

“They wear undercover cameras. We come back with audio and video that back up our words,” he said.

Many shop owners at first hesitated to speak with the league’s investigators, but eventually opened up and displayed their priciest fish maws.

Many shop owners at first hesitated to speak with the league’s investigators, but eventually opened up and displayed their priciest fish maws.

After the Chinese government began paying more attention to the illicit trade in recent years, many merchants responded by selling only to trusted customers and behind closed doors.

However, this level of caution wasn’t universal.

“Chinese laws on illegal wildlife trafficking are harsh, but the problem is the implementation,” Crosta said.

However, this level of caution wasn’t universal.

“Chinese laws on illegal wildlife trafficking are harsh, but the problem is the implementation,” Crosta said.

“It’s not enough to just have the laws. They have to be enforced.”

China’s government launched a campaign last fall to educate merchants on Chinese and Mexican laws banning totoaba fishing and bladder sales.

China’s government launched a campaign last fall to educate merchants on Chinese and Mexican laws banning totoaba fishing and bladder sales.

Still, none of shop owners interviewed by the league could recall any seizures by law enforcement in their region.

On Nan’ao Island, a historical trading hub for fish maws just off the coast of Shantou, an investigator probed a dealer for information.

“If it’s illegal, why do you put them on display?” the investigator asked.

“Because (when) the government comes to check, they call and inform us earlier, and we will hide them when they come,” the merchant explained.

Several shop owners advised the investigators to purchase only the most expensive gold coin fish maw to use as an important business gift or to bribe a government official for an especially lucrative contract.

Investigators found a steady flow of totoaba bladders coming from Mexico into China, and many traders said that’s because they’re betting on a collapse of the species.

On Nan’ao Island, a historical trading hub for fish maws just off the coast of Shantou, an investigator probed a dealer for information.

“If it’s illegal, why do you put them on display?” the investigator asked.

“Because (when) the government comes to check, they call and inform us earlier, and we will hide them when they come,” the merchant explained.

Several shop owners advised the investigators to purchase only the most expensive gold coin fish maw to use as an important business gift or to bribe a government official for an especially lucrative contract.

Investigators found a steady flow of totoaba bladders coming from Mexico into China, and many traders said that’s because they’re betting on a collapse of the species.

The merchants frequently said people buy the gold coin fish maws as investments, speculating that demand will eventually outpace supply and dramatically drive up market values.

A primary smuggling route for totoaba bladders is believed to be from Mexico into the U.S. and then to Hong Kong and China, according to the new report.

A primary smuggling route for totoaba bladders is believed to be from Mexico into the U.S. and then to Hong Kong and China, according to the new report.

Thailand, which critics said also suffers from lax enforcement, is thought to be another key stopover for some shipments.

Shop owners in Shantou said most of the fish bladders were coming from a port on the U.S.-Mexico border, transported in shipping containers alongside legal products such as codfish bladders.

Mexican and U.S. officials have called the totoaba bladder “aquatic cocaine.”

Shop owners in Shantou said most of the fish bladders were coming from a port on the U.S.-Mexico border, transported in shipping containers alongside legal products such as codfish bladders.

Mexican and U.S. officials have called the totoaba bladder “aquatic cocaine.”

In fact, it’s often more expensive, with about two pounds of dried bladder routinely selling for as much as three and a half pounds of the powder drug.

Wildlife trafficking in general is big business, with an estimated annual value of $2 billion in the U.S. and up to $23 billion globally, according to a 2015 report from the nonprofit Defenders of Wildlife in Washington, D.C.

Wildlife trafficking in general is big business, with an estimated annual value of $2 billion in the U.S. and up to $23 billion globally, according to a 2015 report from the nonprofit Defenders of Wildlife in Washington, D.C.

It is routinely ranked among the top illicit trades worldwide.

Moving illegal animal and plant products has drawn the attention of organized crime.

Moving illegal animal and plant products has drawn the attention of organized crime.

In Baja California, drug cartels have been blamed for paying local fishermen to poach the totoaba bladders and then smuggling the contraband.

The value of totoaba bladders in Mexico is approximately $1,500 apiece, according to some law-enforcement agencies.

The value of totoaba bladders in Mexico is approximately $1,500 apiece, according to some law-enforcement agencies.

The pricing surges to about $5,000 per bladder after the organ is smuggled into the U.S.

It’s thought that trafficking of totoaba bladders attracts a lot of opportunists because it’s lucrative and relatively low-risk.

It’s thought that trafficking of totoaba bladders attracts a lot of opportunists because it’s lucrative and relatively low-risk.

Even people on the front lines moving the product rarely face consequences in China, Mexico or the U.S., judging by the scant number of prosecutions in those countries.

“The number of cases have (recently) decreased,” said Michelle Zetwo of San Diego, a special agent with the law-enforcement division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“The number of cases have (recently) decreased,” said Michelle Zetwo of San Diego, a special agent with the law-enforcement division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“That either tells me that the demand is down in China or they’re beating us coming across the border somehow. Or they’re shipping it directly from Mexico to China.”

The most high-profile totoaba case involved the prosecution of a man, Song Shen Zhen, caught crossing the border from Calexico into the U.S. with several of the bladders.

The most high-profile totoaba case involved the prosecution of a man, Song Shen Zhen, caught crossing the border from Calexico into the U.S. with several of the bladders.

After he was let go, Border Patrol agents trailed him to a house where they discovered more than 200 other dried bladders, estimated to have a total street value in China of more than $3.6 million.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office Southern District of California announced in 2014 that Shen Zhen was sentenced to a year in prison and ordered to pay the Mexican government $120,500 in restitution. Under the law, he could have received up to 20 years in prison and a $250,000 fine.

In another case, Los Angeles-based furniture dealer Kam Wing Chan received probation and was ordered to pay $55,000 in restitution for, among other things, possession of several dozen swim bladders.

The conservation organization Sea Shepherd is working in the northern Gulf of California with the blessing of the Mexican Government in attempt to save the embattled vaquita, the smallest cetacean in the world that is on the brink of extinction. Nearing the end of a two-year ban on fishing the area, fishermen will return to the sea with their gill nets if government doesn't delvelop alternative vaquita safe fishing gear.

The U.S. Attorney’s Office Southern District of California announced in 2014 that Shen Zhen was sentenced to a year in prison and ordered to pay the Mexican government $120,500 in restitution. Under the law, he could have received up to 20 years in prison and a $250,000 fine.

In another case, Los Angeles-based furniture dealer Kam Wing Chan received probation and was ordered to pay $55,000 in restitution for, among other things, possession of several dozen swim bladders.

The conservation organization Sea Shepherd is working in the northern Gulf of California with the blessing of the Mexican Government in attempt to save the embattled vaquita, the smallest cetacean in the world that is on the brink of extinction. Nearing the end of a two-year ban on fishing the area, fishermen will return to the sea with their gill nets if government doesn't delvelop alternative vaquita safe fishing gear.

Fishermen in Baja California who catch totoaba largely have escaped serious fines and incarceration.

“Most of the illegal fishermen are not motivated by a little fine. It’s so lucrative,” said Oona Layolle, who heads an advocacy operation in the Upper Gulf of Mexico for the U.S.-based Sea Shepherd Conservation Society.

She oversees two boats that patrol the area, pull up banned gillnets and call in potential poaches to the Mexican navy.

“Every night we see 20 (illegal) fishermen around our ship on the radar, and I know they only arrested seven people in the last two years,” she added.

Mexico’s law-enforcement leaders are promising to step up efforts again the unsanctioned fishing and smuggling.

“Every night we see 20 (illegal) fishermen around our ship on the radar, and I know they only arrested seven people in the last two years,” she added.

Mexico’s law-enforcement leaders are promising to step up efforts again the unsanctioned fishing and smuggling.

Last month, its Congress voted to make such poaching a felony, and a boat with three or more people found catching totoaba can face charges of organized crime.

So far, these measures haven’t seemed to slow down fishermen in the upper Gulf, who sell totoaba bladders to middlemen in and around the town of San Felipe, said Sean Bogle, an investigative filmmaker with the nonprofit Wild Lens.

“A fisherman will go out and fish for totoaba, and they’re usually removing the bladder in the boat,” he said.

So far, these measures haven’t seemed to slow down fishermen in the upper Gulf, who sell totoaba bladders to middlemen in and around the town of San Felipe, said Sean Bogle, an investigative filmmaker with the nonprofit Wild Lens.

“A fisherman will go out and fish for totoaba, and they’re usually removing the bladder in the boat,” he said.

“When they hit shore, there is an individual waiting for them, someone involved in an organized syndicate of sorts.”

Bogle recently directed the documentary “Souls of the Vermilion Sea,” which chronicles the impact of totoaba poaching on the dwindling vaquita population.

Bogle recently directed the documentary “Souls of the Vermilion Sea,” which chronicles the impact of totoaba poaching on the dwindling vaquita population.

In the process, he interviewed anglers and government officials close to the supply chain.

“From what I understand, going through the U.S. is the most common (smuggling) route,” Bogle said.

“From what I understand, going through the U.S. is the most common (smuggling) route,” Bogle said.

“There’s definitely reports of it going out of San Diego, particularly on container ships.”

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire