By Jon Emont

Muslims demonstrating on Dec. 21 last year in front of China’s embassy in Jakarta, protesting the treatment of members of the mostly Muslim ethnic Uighur minority in East Turkestan.

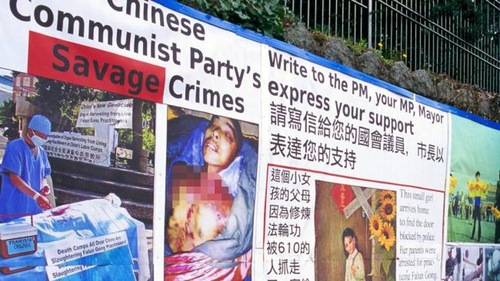

JAKARTA, Indonesia—A year ago, clerics here in the world’s largest Muslim-majority country expressed alarm over China’s treatment of ethnic-minority Muslims—around a million of whom have been detained in concentration camps, according to human-rights groups.

Leaders of Muhammadiyah, Indonesia’s second-largest Muslim organization, issued an open letter in December 2018 noting reports of violence against the “weak and innocent” community of Uighurs, who are mostly Muslims, and appealing to Beijing to explain.

Soon after, Beijing sprang into action with a concerted campaign to convince Indonesia’s religious authorities and journalists that the concentration camps in China’s northwestern East Turkestan colony are a well-meaning effort to provide job training and combat extremism.

More than a dozen top Indonesian religious leaders were taken to East Turkestan and visited re-education facilities.

Soon after, Beijing sprang into action with a concerted campaign to convince Indonesia’s religious authorities and journalists that the concentration camps in China’s northwestern East Turkestan colony are a well-meaning effort to provide job training and combat extremism.

More than a dozen top Indonesian religious leaders were taken to East Turkestan and visited re-education facilities.

Tours for journalists and academics followed.

Chinese authorities gave presentations on terrorist attacks by Uighurs and invited visitors to pray at local mosques.

In the camps they visited classrooms where they were told students received training in everything from hotel management to animal husbandry.

Views in Indonesia changed.

Views in Indonesia changed.

A senior Muhammadiyah religious scholar who went on the tour was quoted in the group’s official magazine as saying a camp he visited was excellent, had comfortable classrooms and wasn’t like a prison.

A watchtower at what is a concentration camp on the outskirts of Hotan, in China's northwestern East Turkestan colony.

China’s effort to shape opinions—bolstered by donations and other financial support—has helped to blunt criticism of its treatment of Uighurs by Muslim-majority nations—in contrast to the outspoken condemnation it has received from the U.S. and other Western nations.

Indonesia has been on the front lines of this effort.

Indonesia has been on the front lines of this effort.

For months China has worked to persuade clerics, politicians and journalists to support its policies in East Turkestan and courted social-media influencers to promote a more favorable view of China and showcase Islamic culture in the country.

“There’s a problem” with extremism in East Turkestan “and they’re handling it,” said Masduki Baidlowi, an official with Nahdlatul Ulama, Indonesia’s largest Muslim organization, who was also visited the region on the tour.

“There’s a problem” with extremism in East Turkestan “and they’re handling it,” said Masduki Baidlowi, an official with Nahdlatul Ulama, Indonesia’s largest Muslim organization, who was also visited the region on the tour.

“They provide a solution: life skills, a vocation,” he said.

He acknowledged he had some concerns—there was no place for detainees to pray, for example—which the delegation raised with officials.

Earlier this month, a top East Turkestan government official said all students learning vocational skills at the centers had graduated.

He acknowledged he had some concerns—there was no place for detainees to pray, for example—which the delegation raised with officials.

Earlier this month, a top East Turkestan government official said all students learning vocational skills at the centers had graduated.

Rights activists expressed skepticism that this meant all detained Muslims had been released.

Journalists from Indonesia and Malaysia conducted an interview at an Islamic college in Urumqi, East Turkestan, on March 1, 2019.

Journalists from Indonesia and Malaysia conducted an interview at an Islamic college in Urumqi, East Turkestan, on March 1, 2019.

Journalists from Indonesia and Malaysia conducted an interview at an Islamic college in Urumqi, East Turkestan, on March 1, 2019.

Journalists from Indonesia and Malaysia conducted an interview at an Islamic college in Urumqi, East Turkestan, on March 1, 2019. In July, a host of Muslim-majority nations, including Saudi Arabia, Iran, Egypt, Syria and the United Arab Emirates, joined North Korea, Myanmar and others in signing a letter to the United Nations Human Rights Council praising China’s governance of East Turkestan.

“Now safety and security has returned to East Turkestan and the fundamental human rights of people of all ethnic groups there are safeguarded,” the letter said.

Uighur activists, in contrast, condemn China’s actions in East Turkestan, saying China is wrongfully imprisoning large portions of the population, breaking up families, silencing intellectuals and razing holy sites as it seeks to destroy Uighurs’ religion and culture and force them to assimilate into broader Chinese society.

The U.S. government says China has detained more than one million Muslims, and groups such as Human Rights Watch have offered similar estimates.

Individuals can be targeted for matters as minor as reciting from the Quran at a funeral, according to the U.S. State Department.

A message from a Communist Party commission in charge of East Turkestan security encouraged cadres there in East Turkestan to “promote the repentance and confession of the students for them to understand deeply the illegal, criminal, and dangerous nature of their past behavior,” according to documents uncovered by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

China has built up goodwill in Indonesia in recent years through programs like scholarships for students affiliated with Nahdlatul Ulama, which has tens of millions of followers and presents itself as a champion of moderate Islam.

China has built up goodwill in Indonesia in recent years through programs like scholarships for students affiliated with Nahdlatul Ulama, which has tens of millions of followers and presents itself as a champion of moderate Islam.

This year, Nahdlatul Ulama’s Beijing branch published a book of essays by supporters who had studied in China, some of which questioned the scale of the camp system and whether Muslims were mistreated.

Nahdlatul Ulama head Said Aqil Siroj —who has broken the fast on Ramadan for years with China’s ambassador—implored readers in the book’s foreword not to rely on media and international television reports to understand East Turkestan.

Siroj didn’t immediately respond to an email requesting comment.

Nahdlatul Ulama head Said Aqil Siroj —who has broken the fast on Ramadan for years with China’s ambassador—implored readers in the book’s foreword not to rely on media and international television reports to understand East Turkestan.

Siroj didn’t immediately respond to an email requesting comment.

A senior official at Nahdlatul Ulama didn’t respond to a message asking about China’s possible influence over the organization.

Not all Muslim clerics who have gone on China-sponsored trips to East Turkestan have backed China’s line.

Not all Muslim clerics who have gone on China-sponsored trips to East Turkestan have backed China’s line.

Muhyiddin Junaidi, head of international relations for Majelis Ulama Indonesia, a powerful Indonesian clerical body, said that his February visit was tightly controlled and that Uighurs he met seemed afraid to express themselves.

A photo from Sept. 13, 2019, shows what used to be a Uighur cemetery, in Kuche, East Turkestan.

He said Beijing’s frequent invitations to influential Indonesians was designed to “brainwash public opinion,” and criticized Indonesian Muslims he said had become apologists for China.

Still, the blizzard of outreach has made it difficult for more-critical Indonesian Muslim scholars to speak out.

One prominent Indonesian Islamic scholar opposed to China’s policies in East Turkestan posted a critical report by Human Rights Watch on his Facebook page, only to be accused by other Muslim leaders of amplifying Western propaganda.

The U.S. has countered by having diplomats meet and pose skeptical questions to clerics after East Turkestan tours.

In August, the U.S. sponsored a Facebook Live discussion on China’s mistreatment of Muslim minorities “to draw attention to these abuses,” according to a notice for the event, and invited Indonesians to attend a meeting in a mall.

U.S. diplomats have also lobbied Indonesian counterparts to press Chinese officials to release ethnic minority Muslims, a person familiar with the effort said.

The U.S. has countered by having diplomats meet and pose skeptical questions to clerics after East Turkestan tours.

In August, the U.S. sponsored a Facebook Live discussion on China’s mistreatment of Muslim minorities “to draw attention to these abuses,” according to a notice for the event, and invited Indonesians to attend a meeting in a mall.

U.S. diplomats have also lobbied Indonesian counterparts to press Chinese officials to release ethnic minority Muslims, a person familiar with the effort said.

U.S. officials “realize that the Chinese embassy is doing similar things, with—frustratingly—a bigger budget,” the person said.

“We have expressed our concerns about China’s treatment of its own citizens in meetings with Indonesian officials and members of civil society,” a U.S. Embassy official said.

“We have expressed our concerns about China’s treatment of its own citizens in meetings with Indonesian officials and members of civil society,” a U.S. Embassy official said.

After locking up as many as a million people in concentration camps in East Turkestan, Chinese authorities are destroying Uighur neighborhoods and purging the region's culture. They say they’re fighting terrorism. Their aim: to engineer a society loyal to Beijing.

Bayu Hermawan, a journalist for Indonesian newspaper Republika, traveled to East Turkestan on a Beijing-organized tour in February, and wrote articles that cited camp residents who said they weren’t given trials or were brought in for offenses like adhering to a Muslim diet.

Mr. Hermawan received a WhatsApp message from a Chinese embassy employee in Jakarta, saying he was disappointed by the article because it didn’t focus on positive aspects of the trip, according to the message shown to The Wall Street Journal.

Around that time, Republika’s website faced a distributed denial-of-service cyberattack, according to two employees, making the website slow to load and inaccessible from abroad.

Bayu Hermawan, a journalist for Indonesian newspaper Republika, traveled to East Turkestan on a Beijing-organized tour in February, and wrote articles that cited camp residents who said they weren’t given trials or were brought in for offenses like adhering to a Muslim diet.

Mr. Hermawan received a WhatsApp message from a Chinese embassy employee in Jakarta, saying he was disappointed by the article because it didn’t focus on positive aspects of the trip, according to the message shown to The Wall Street Journal.

Around that time, Republika’s website faced a distributed denial-of-service cyberattack, according to two employees, making the website slow to load and inaccessible from abroad.

Fitriyan Zamzami, an editor at Republika, said IT workers traced the attack to accounts in places like Bulgaria and Ukraine; still, he said, the timing was suspicious.

China’s Embassy in Indonesia has also supported tours of Indonesian social-media influencers to visit Chinese cities outside of East Turkestan.

China’s Embassy in Indonesia has also supported tours of Indonesian social-media influencers to visit Chinese cities outside of East Turkestan.

This was a part of a broader effort to limit anti-China sentiment in Indonesia and expose Indonesians to Muslim life in China, according to Riyadi Suparno, the head of Tenggara Strategics, an Indonesian investment research and advisory institute that helped organize a recent tour.

He said the influencers were paid a per diem of $500 and they were free to post whatever they liked.

“Yes a mosque!” wrote Alya Nurshabrina, a tour participant and former Miss Indonesia to her roughly 86,000 followers on Instagram, outside of one in Beijing.

“Yes a mosque!” wrote Alya Nurshabrina, a tour participant and former Miss Indonesia to her roughly 86,000 followers on Instagram, outside of one in Beijing.

“China welcomes every religion.”

A recent report by the Uyghur Human Rights Project, a nongovernment organization, found that more than 100 mosques have been damaged or destroyed in Beijing’s recent campaign in East Turkestan.

A recent report by the Uyghur Human Rights Project, a nongovernment organization, found that more than 100 mosques have been damaged or destroyed in Beijing’s recent campaign in East Turkestan.

Cemeteries and other structures with Uighur Islamic architecture also have been destroyed.

When asked if her social-media postings offered a misleading portrait of China’s treatment of Islam, Nurshabrina said her postings reflected her own experiences on the trip.

Omer Kanat, an ethnic Uighur who directs the Uyghur Human Rights Project in Washington, visited Jakarta earlier this year to lobby Islamic leaders to speak out against what he described as China’s use of detention camps to indoctrinate Uighurs and eliminate Islam.

He said some Indonesian Muslims leaders had already been visited by Chinese diplomats, and they were suspicious, asking him whether it was an American conspiracy that China mistreats Uighurs.

“They were so convinced with what the Chinese said,” Mr. Kanat said.

When asked if her social-media postings offered a misleading portrait of China’s treatment of Islam, Nurshabrina said her postings reflected her own experiences on the trip.

Omer Kanat, an ethnic Uighur who directs the Uyghur Human Rights Project in Washington, visited Jakarta earlier this year to lobby Islamic leaders to speak out against what he described as China’s use of detention camps to indoctrinate Uighurs and eliminate Islam.

He said some Indonesian Muslims leaders had already been visited by Chinese diplomats, and they were suspicious, asking him whether it was an American conspiracy that China mistreats Uighurs.

“They were so convinced with what the Chinese said,” Mr. Kanat said.

Before After: Dome removed

Before After: Dome removed

A gate of what is officially known as a ‘vocational skills education centre’ in Dabancheng, in East Turkestan

A gate of what is officially known as a ‘vocational skills education centre’ in Dabancheng, in East Turkestan Uighur Muslim worshipers attend an early afternoon prayer session at the Kashgar Idgah mosque in East Turkestan. Photo taken August 5, 2008.

Uighur Muslim worshipers attend an early afternoon prayer session at the Kashgar Idgah mosque in East Turkestan. Photo taken August 5, 2008.

Congressional lawmakers singled out Chen Quanguo, who became party chief of East Turkestan in 2016, for sanctions among seven Chinese officials.

Congressional lawmakers singled out Chen Quanguo, who became party chief of East Turkestan in 2016, for sanctions among seven Chinese officials.