Appeasement of aggressors is far more dangerous than measured confrontation.

Book review: Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap, by Graham Allison (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2017)

By Arthur Waldron

By Arthur Waldron

Arthur Waldron is a notable scholar of Chinese history and military affairs. In this book review, he argues persuasively against a fallacious concept that has become a pillar of establishment thinking on China.

In 1938, Chamberlain led the European chorus to appease Hitler by agreeing to his expansionist plans. The Munich Agreement served Hitler with Czechoslovakia on a silver platter. Chamberlain was naive enough to proclaim that the agreement had brought "peace in our time."

In 1938, Chamberlain led the European chorus to appease Hitler by agreeing to his expansionist plans. The Munich Agreement served Hitler with Czechoslovakia on a silver platter. Chamberlain was naive enough to proclaim that the agreement had brought "peace in our time."

79 years after, Donald Trump tried to appease Xi Jinping

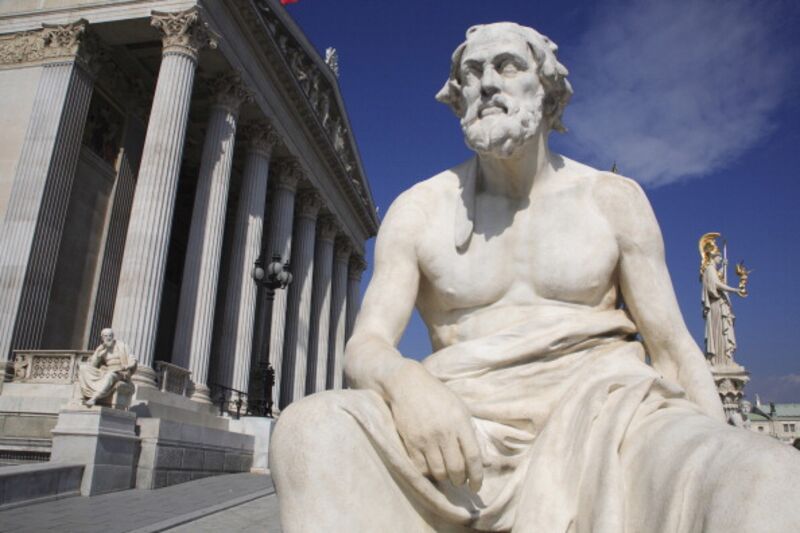

Let us start by observing that perhaps the two greatest classicists of the last century, Professor Donald Kagan of Yale and the late Professor Ernst Badian of Harvard, long ago proved that no such thing exists as the “Thucydides Trap,” certainly not in the actual Greek text of the great History of the Peloponnesian War, perhaps the greatest single work of history ever.

Astonishingly, even the names of these two towering academic giants are absent from the index of this baffling academic farrago.

79 years after, Donald Trump tried to appease Xi Jinping

Let us start by observing that perhaps the two greatest classicists of the last century, Professor Donald Kagan of Yale and the late Professor Ernst Badian of Harvard, long ago proved that no such thing exists as the “Thucydides Trap,” certainly not in the actual Greek text of the great History of the Peloponnesian War, perhaps the greatest single work of history ever.

Astonishingly, even the names of these two towering academic giants are absent from the index of this baffling academic farrago.

It was penned by Graham Allison, a Harvard professor — associated with the Kennedy School of Government — to whom questions along the lines of “How did you write about The Iliad without mentioning Homer?” should be addressed.

Allison’s argument draws on one sentence of Thucydides’s text: “What made war inevitable was the growth of Athenian Power and the fear which this caused in Sparta.”

Allison’s argument draws on one sentence of Thucydides’s text: “What made war inevitable was the growth of Athenian Power and the fear which this caused in Sparta.”

This lapidary summing up of an entire argument is justly celebrated.

It introduced to historiography the idea that wars may have “deep causes,” that resident powers are tragically fated to attack rising powers.

It is brilliant and important, no question, but is it correct?

Clearly not for the Peloponnesian War.

Clearly not for the Peloponnesian War.

Generations of scholars have chewed over Thucydides’s text.

Every battlefield has been measured.

The quantity of academic literature on the topic is overwhelming, dating as far back as 1629 when Thomas Hobbes produced the first English translation.

In the present day, Kagan wrote four volumes in which he modestly but decisively overturned the idea of the Thucydides Trap.

In the present day, Kagan wrote four volumes in which he modestly but decisively overturned the idea of the Thucydides Trap.

Badian did the same.

The problem is that although Thucydides presents the war as started by the resident power, Sparta, out of fear of a rising Athens, he makes it clear first that Athens had an empire, from which it wished to eliminate any Spartan threat by stirring up a war and teaching the hoplite Spartans that they could never win.

The problem is that although Thucydides presents the war as started by the resident power, Sparta, out of fear of a rising Athens, he makes it clear first that Athens had an empire, from which it wished to eliminate any Spartan threat by stirring up a war and teaching the hoplite Spartans that they could never win.

The Spartans, Kagan tells us, wanted no war, preemptive or otherwise.

Dwelling in the deep south, they lived a simple country life that agreed with them.

They used iron bars for money and lived on bean soup when not practicing fighting, their main activity.

Athens’s rival Corinth, which also wanted a war for her own reasons, taunted the young Spartans into unwonted bellicosity such that they would not even listen to their king, Archidamus, who spoke eloquently against war.

Once started, the war was slow to catch fire.

Archidamus urged the Athenians to make a small concession — withdraw the Megarian Decree, which embargoed a small, important state — and call it a day.

But the Athenians rejected his entreaties.

Then plague struck Athens, killing, among others, the leading citizen Pericles.

Both Kagan and Badian note that the reason that the independent states of Hellas, including Athens and Sparta, had lived in peace became clear.

Both Kagan and Badian note that the reason that the independent states of Hellas, including Athens and Sparta, had lived in peace became clear.

Although their peoples were not acquainted, their leaders formed a web of friendship that managed things.

The plague eliminated Pericles, the key man in this peace-keeping mechanism.

Uncontrolled popular passions took over, and the war was revived, invigorated.

It would end up destroying Athens, which had started it.

Preemption would have been an incomprehensible concept to the Spartans, but war was not, and when the Athenians forced them into one, they ended up victors.

The whole Thucydides Trap — not clear who coined this false phrase — does not exist, even in its prime example.

So now we can turn to the hash Allison makes of the unfamiliar material he has chosen.

Ignoring all this, Allison takes Thucydides literally: Wars (sometimes) begin when rising powers like Athens threaten established powers like Sparta.

Ignoring all this, Allison takes Thucydides literally: Wars (sometimes) begin when rising powers like Athens threaten established powers like Sparta.

But do they really?

The case is difficult to make.

Japan was the rising power in 1904 while Russia was long established. Did Russia therefore seek to preempt Japan?

No.

The Japanese launched a surprise attack on Russia, scuttling the Czar’s fleet.

In 1941, the Japanese were again the rising power. Did ever-vigilant America strike out to eliminate the Japanese threat?

Wrong.

Roosevelt considered it “infamy” when Japan surprised him by attacking Pearl Harbor at a time when the world was already in flames.

Switch to Europe — in the 1930s, Germany was obviously the rising, menacing power.

Did France, Russia, England, and the other threatened powers move against it?

They could not even form an alliance, so the USSR eventually joined Hitler rather than fight him.

Exceptions there are, and Allison makes a half-baked effort to find them, but these are not the mainstream.

Is this some kind of immense academic lapse?

No.

No.

What has really happened is that Allison has caught China fever, not hard around Harvard, although knowing no Chinese language and little Chinese history.

As a result, Allison seems to have been impressed above all by Chinese numbers: population, army size, growth rate, steel production, etc.

As a result, Allison seems to have been impressed above all by Chinese numbers: population, army size, growth rate, steel production, etc.

So if that sentence from Thucydides is correct, then China is clearly a rising power that will want her “place in the sun” — which will lead ineluctably to a collision between rising China (Athens) instigated by the presumably setting U.S. (Sparta), which will see military preemption as the only recourse to avert a loss of power and a Chinese-dominated world.

To escape this trap, Allison demands that we must find a way to give China what she wants and forget the lessons of so many previous wars.

Many of Allison’s colleagues at Harvard also believe this to be true.

The reality, however, is that Allison’s recipe is actually a recipe for war.

The reality, however, is that Allison’s recipe is actually a recipe for war.

Appeasement of aggressors is far more dangerous than measured confrontation.

Did China become more aggressive in the South China Sea in the 2000s because the Obama administration got tougher or because it went AWOL on the issue?

I’d say the latter is more likely.

When it comes to China, we might want to be more mindful of the “Chamberlain Trap” after the peace-loving prime minister of England, one of the authors of the disastrous 1938 Munich agreement that sought to avoid war by concessions, which in fact taught Hitler that the British were easily fooled.

That is the trap we are in urgent need of avoiding.

As an intellectual exercise, let us try making the modest substitution in Allison’s argument of Europe for China.

As an intellectual exercise, let us try making the modest substitution in Allison’s argument of Europe for China.

Europe — excluding Russia and some other, smaller, countries — has a land area of 3.9 million square miles, which is to say larger than the U.S. at 3.79 million.

The European Union GDP is roughly $20 trillion (nominal) while that of the United States perhaps $1 trillion less.

Europe had 1,823,000 forces in uniform in 2014, compared with 1,031,000 for the United States today.

Where am I going?

Where am I going?

If we add educational and technical levels as well as standard of living, one might be forgiven for thinking that, by the numbers, Europe, not China, was the leading potential challenger to the United States.

That of course is what the late Jean-Jacques Servan-Schrieber argued in his immensely popular and influential bit of futurology Le Défi Américan [“The American Challenge”] in 1967.

It may well be that the great, almost unspoken question of this century is the future of Europe.

So far, however, Europe and America have not proven “destined to war.”

Nor are America and China.

Nor are America and China.

My late colleague and mentor Ambassador James Lilley liked to recall a lecture given by an American professor about Taiwan.

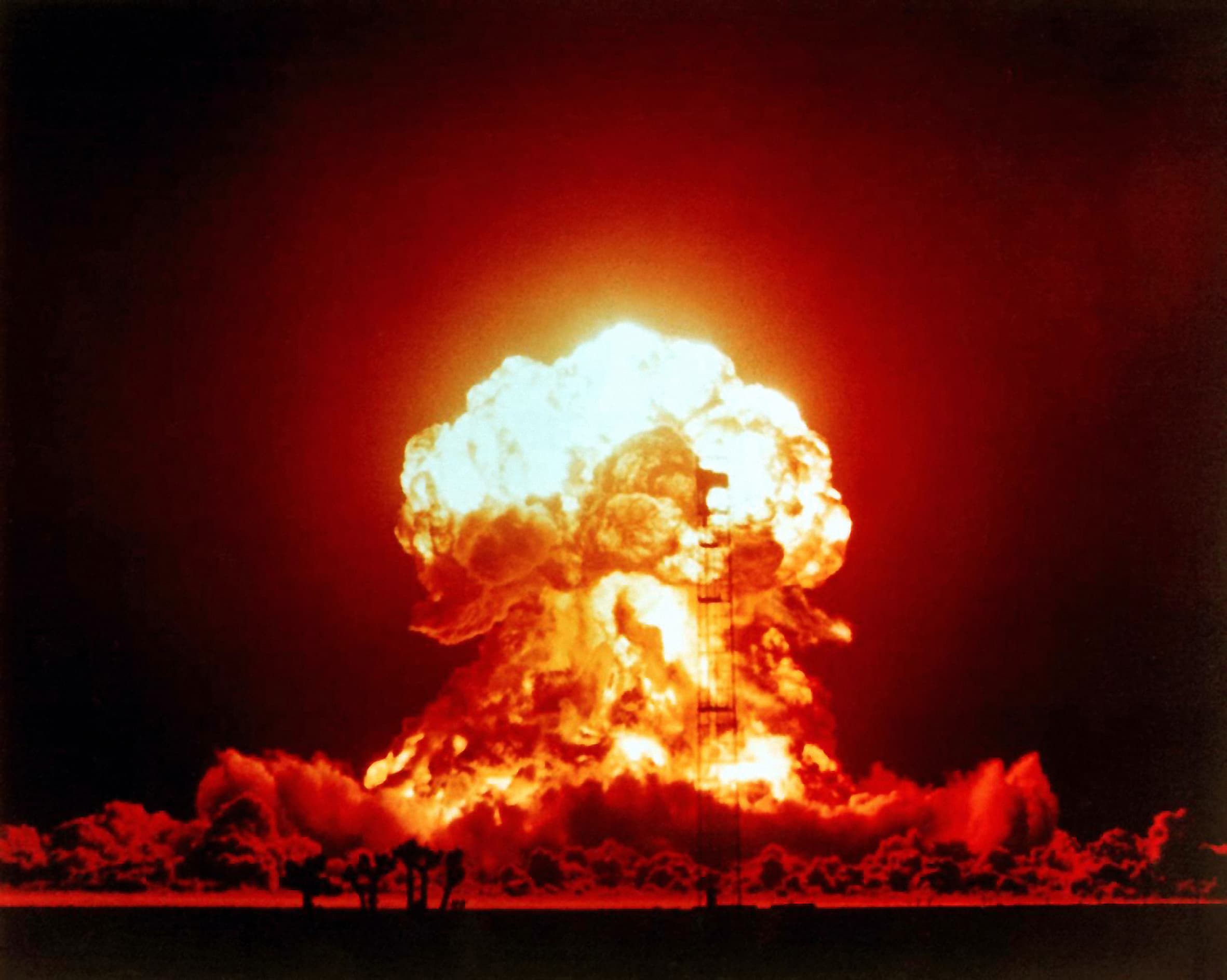

The speaker became increasingly heated, declaring that unless Washington immediately yielded to Beijing’s demands about Taiwan, a nuclear war was unavoidable.

A PLA general in attendance was at first puzzled, and then agitated.

He turned to the ambassador to whisper a question: “Who is this guy? Does he think we are crazy?” In other words, come whatever, we Chinese are intelligent enough to realize that war — not to mention nuclear war — with the United States would be an insane action that would destroy all China has achieved in the years since Mao’s death in 1976.

As I see it, it’s far more likely, but certainly not as sexy, to believe that there will be no “destined” war between China and the U.S. because the Chinese might actually have a clearer reading of history than the scholars at Harvard.

Allison’s book is chock-a-block with facts.

And the impressive statistics of China’s growth in military power that Allison cites are real.

Allison’s book is chock-a-block with facts.

And the impressive statistics of China’s growth in military power that Allison cites are real.

So are its advances in technology.

Furthermore, since 1995, two years before Deng Xiaoping’s death, Beijing simply used military force to seize a maritime formation called “Mischief Reef” from the Philippines — a clear reversal of Deng’s policy of always maintaining good relations with the United States.

Furthermore, since 1995, two years before Deng Xiaoping’s death, Beijing simply used military force to seize a maritime formation called “Mischief Reef” from the Philippines — a clear reversal of Deng’s policy of always maintaining good relations with the United States.

By 2012, China had occupied the Philippines’ Scarborough Shoal as well, and continues to do so, while fortifying and creating islands in the South China Sea, where long runways were built for military aircraft, rockets deployed, submarines anchored, and in the East China Sea promulgating an Air Defense Identification Zone that just happened to include one Korean island China would like, and another group of such Japanese islands.

In other words, since Ambassador Lilley took his friend to hear the American professor, Chinese policy seems to have changed, but how much, and more importantly, why?

Since the attack on Scarborough Shoal, now six years ago, my own opinion is that China expected to have occupied a lot more.

Her slightly delusional view of her claims, first made explicit in ASEAN’s winter meeting of 2010 in Hanoi, was that “small” countries would all bow respectfully to China’s new preeminence.

This has failed to occur.

All of China’s neighbors are now building up strong military capabilities.

Japanese and South Korean nuclear weapons are even a possibility.

Overrelying on their traditional concept of awesomeness (威 wēi), the Chinese expected a cakewalk. They have got instead an arms race with neighbors including Japan and other American allies and India, too.

With so much firepower now in place, the danger of accident, pilot error, faulty command and control, etc. must be considered.

But I’d wager that the Chinese would smother an unintended conflict.

They are, after all, not idiots.

Allison also provides us with a mélange of statistics showing the great industrial might of China.

She produces tons of steel, more than markets can absorb, likewise coal, while serving as the workshop of the world where the computer on which I am writing was manufactured.

The mountains of Chinese exports that have shuttered manufacturing in America seem, like the American powerhouse of 50 years ago, set to overwhelm the world rather as Servan-Schreiber expected American-owned business to do in Europe — but did not.

China’s tremendous economic vulnerabilities have no mention in Allison’s book.

But they are critical to any reading of China’s future.

China imports a huge amount of its energy and is madly planning a vast expansion in nuclear power, including dozens of reactors at sea.

She has water endowments similar to Sudan, which means nowhere near enough.

The capital intensity of production is very high: In China, one standard energy unit used fully produces 33 cents of product.

In India, the figure is 77 cents.

Gradually climb and you get to $3 in Europe and then — in Japan — $5.55.

China is poor not only because she wastes energy but water, too, while destroying her ecology in a way perhaps lacking any precedent.

Figures such as these are very difficult to find: Mine come from researchers in the energy sector. Solving all of this, while making the skies blue, is a task of both extraordinary technical complexity and expense that will put China’s competing special interests at one another’s throats.

Not solving, however, will doom China’s future.

Allison may know this on some level, but you have to spend a lot of time in China and talk to a lot of specialists (often in Chinese) before the enormity becomes crushingly real.

What’s more, Chinese are leaving China in unprecedented numbers.

The late Richard Solomon, who worked on U.S.-China relations for decades, remarked to me a few weeks before his death that “one day last year all the Chinese who could decided to move away.” Why?

The pollution might kill your infants; the hospitals are terrible, the food is adulterated, the system corrupt and unpredictable.

Here in the Philadelphia suburbs and elsewhere, thousands of Chinese buyers are flocking to buy homes in cash.

Even Xi Jinping sent his daughter to Harvard.

Does that imply a high-profile political career for her in China?

Probably not.

It rather implies a quiet retirement with Xi’s grandchildren over here.

Our American private secondary schools are inundated by Chinese applicants.

For the first time this year, my Chinese graduate students are marrying one another and buying houses here.

This is a leading indicator.

If it could be done, the coming tsunami would bring 10 million highly qualified Chinese families to the U.S. in 10 years — along with fleeing crooks, spies, and other flotsam and jetsam.

Even Xi’s first wife fled China; she lives in England.

Allison, however, misses this; “immigration” is not in his index.

Instead, he speculates about war, based on some superficial reading and sampling of the literature, coming to the question “What does Xi want?” — which I take as meaning that he thinks Xi’s opinion matters — which makes nonsense of the vast determining waves of economic development, not to mention his glance at Thucydides — with the opinion following that somehow we should try to find out what that is and cut a deal.

This is geopolitics from a Harvard professor?

This is the great wave of history?

How to conclude a look at so ill conceived and sloppily executed a book?

Do not blame Allison.

The problem is the pervasive lack of knowledge of China — a country which is, after all, run by the Communist Party, the police, and the army, and thus difficult to get to know.

This black hole of information has perversely created an overabundance of fantasies, some very pessimistic, some as absurdly bright as a foreigner on the payroll can make them.

Forget the fantasies, therefore, and look at the facts.

In the decades ahead, China will have to solve immense problems simply to survive.

Neither her politics nor her economy follow any rules that are known.

The miracle, like the German Wirtschaftswunder and the vertical ascent of Japan, is already coming to an end.

A military solution offers only worse problems.

In other words, since Ambassador Lilley took his friend to hear the American professor, Chinese policy seems to have changed, but how much, and more importantly, why?

Since the attack on Scarborough Shoal, now six years ago, my own opinion is that China expected to have occupied a lot more.

Her slightly delusional view of her claims, first made explicit in ASEAN’s winter meeting of 2010 in Hanoi, was that “small” countries would all bow respectfully to China’s new preeminence.

This has failed to occur.

All of China’s neighbors are now building up strong military capabilities.

Japanese and South Korean nuclear weapons are even a possibility.

Overrelying on their traditional concept of awesomeness (威 wēi), the Chinese expected a cakewalk. They have got instead an arms race with neighbors including Japan and other American allies and India, too.

With so much firepower now in place, the danger of accident, pilot error, faulty command and control, etc. must be considered.

But I’d wager that the Chinese would smother an unintended conflict.

They are, after all, not idiots.

Allison also provides us with a mélange of statistics showing the great industrial might of China.

She produces tons of steel, more than markets can absorb, likewise coal, while serving as the workshop of the world where the computer on which I am writing was manufactured.

The mountains of Chinese exports that have shuttered manufacturing in America seem, like the American powerhouse of 50 years ago, set to overwhelm the world rather as Servan-Schreiber expected American-owned business to do in Europe — but did not.

China’s tremendous economic vulnerabilities have no mention in Allison’s book.

But they are critical to any reading of China’s future.

China imports a huge amount of its energy and is madly planning a vast expansion in nuclear power, including dozens of reactors at sea.

She has water endowments similar to Sudan, which means nowhere near enough.

The capital intensity of production is very high: In China, one standard energy unit used fully produces 33 cents of product.

In India, the figure is 77 cents.

Gradually climb and you get to $3 in Europe and then — in Japan — $5.55.

China is poor not only because she wastes energy but water, too, while destroying her ecology in a way perhaps lacking any precedent.

Figures such as these are very difficult to find: Mine come from researchers in the energy sector. Solving all of this, while making the skies blue, is a task of both extraordinary technical complexity and expense that will put China’s competing special interests at one another’s throats.

Not solving, however, will doom China’s future.

Allison may know this on some level, but you have to spend a lot of time in China and talk to a lot of specialists (often in Chinese) before the enormity becomes crushingly real.

What’s more, Chinese are leaving China in unprecedented numbers.

The late Richard Solomon, who worked on U.S.-China relations for decades, remarked to me a few weeks before his death that “one day last year all the Chinese who could decided to move away.” Why?

The pollution might kill your infants; the hospitals are terrible, the food is adulterated, the system corrupt and unpredictable.

Here in the Philadelphia suburbs and elsewhere, thousands of Chinese buyers are flocking to buy homes in cash.

Even Xi Jinping sent his daughter to Harvard.

Does that imply a high-profile political career for her in China?

Probably not.

It rather implies a quiet retirement with Xi’s grandchildren over here.

Our American private secondary schools are inundated by Chinese applicants.

For the first time this year, my Chinese graduate students are marrying one another and buying houses here.

This is a leading indicator.

If it could be done, the coming tsunami would bring 10 million highly qualified Chinese families to the U.S. in 10 years — along with fleeing crooks, spies, and other flotsam and jetsam.

Even Xi’s first wife fled China; she lives in England.

Allison, however, misses this; “immigration” is not in his index.

Instead, he speculates about war, based on some superficial reading and sampling of the literature, coming to the question “What does Xi want?” — which I take as meaning that he thinks Xi’s opinion matters — which makes nonsense of the vast determining waves of economic development, not to mention his glance at Thucydides — with the opinion following that somehow we should try to find out what that is and cut a deal.

This is geopolitics from a Harvard professor?

This is the great wave of history?

How to conclude a look at so ill conceived and sloppily executed a book?

Do not blame Allison.

The problem is the pervasive lack of knowledge of China — a country which is, after all, run by the Communist Party, the police, and the army, and thus difficult to get to know.

This black hole of information has perversely created an overabundance of fantasies, some very pessimistic, some as absurdly bright as a foreigner on the payroll can make them.

Forget the fantasies, therefore, and look at the facts.

In the decades ahead, China will have to solve immense problems simply to survive.

Neither her politics nor her economy follow any rules that are known.

The miracle, like the German Wirtschaftswunder and the vertical ascent of Japan, is already coming to an end.

A military solution offers only worse problems.