By Paul Mozur and Cecilia Kang

A Huawei billboard in Shanghai. The deals with United States companies will help Huawei continue to sell its smartphones and other products.

SHANGHAI — United States chip makers are still selling millions of dollars of products to Huawei despite a Trump administration ban on the sale of American technology to the Chinese telecommunications giant.

Industry leaders including Intel and Micron have found ways to avoid labeling goods as American-made, said the people, who spoke on the condition they not be named because they were not authorized to disclose the sales.

Goods produced by American companies overseas are not always considered American-made.

The components began to flow to Huawei about three weeks ago, the people said.

The sales will help Huawei continue to sell products such as smartphones and servers, and underscore how difficult it is for the Trump administration to clamp down on companies that it considers a national security threat, like Huawei.

The sales will help Huawei continue to sell products such as smartphones and servers, and underscore how difficult it is for the Trump administration to clamp down on companies that it considers a national security threat, like Huawei.

They also hint at the possible unintended consequences from altering the web of trade relationships that ties together the world’s electronics industry and global commerce.

The Commerce Department’s move to block sales to Huawei, by putting it on a so-called entity list, set off confusion within the Chinese company and its many American suppliers, the people said. Many executives lacked deep experience with American trade controls, leading to initial suspensions in shipments to Huawei until lawyers could puzzle out which products could be sent.

The Commerce Department’s move to block sales to Huawei, by putting it on a so-called entity list, set off confusion within the Chinese company and its many American suppliers, the people said. Many executives lacked deep experience with American trade controls, leading to initial suspensions in shipments to Huawei until lawyers could puzzle out which products could be sent.

Decisions about what can and cannot be shipped were also often run by the Commerce Department.

American companies like Intel sell technology supporting current Huawei products until mid-August.

American companies like Intel sell technology supporting current Huawei products until mid-August.

American companies may sell technology supporting current Huawei products until mid-August.

But a ban on components for future Huawei products is already in place.

It’s not clear what percentage of the current sales were for future products.

The sales have most likely already totaled hundreds of millions of dollars, the people estimated.

While the Trump administration has been aware of the sales, officials are split about how to respond, the people said.

While the Trump administration has been aware of the sales, officials are split about how to respond, the people said.

Some officials feel that the sales violate the spirit of the law and undermine government efforts to pressure Huawei, while others are more supportive because it lightens the blow of the ban for American corporations.

Huawei has said it buys around $11 billion in technology from United States companies each year.

Intel and Micron declined to comment.

“As we have discussed with the U.S. government, it is now clear some items may be supplied to Huawei consistent with the entity list and applicable regulations,” John Neuffer, the president of the Semiconductor Industry Association, wrote in a statement on Friday.

“Each company is impacted differently based on their specific products and supply chains, and each company must evaluate how best to conduct its business and remain in compliance.”

In an earnings call Tuesday afternoon, Micron’s chief executive, Sanjay Mehrotra, said the company stopped shipments to Huawei after the Commerce Department’s action last month.

Intel and Micron declined to comment.

“As we have discussed with the U.S. government, it is now clear some items may be supplied to Huawei consistent with the entity list and applicable regulations,” John Neuffer, the president of the Semiconductor Industry Association, wrote in a statement on Friday.

“Each company is impacted differently based on their specific products and supply chains, and each company must evaluate how best to conduct its business and remain in compliance.”

In an earnings call Tuesday afternoon, Micron’s chief executive, Sanjay Mehrotra, said the company stopped shipments to Huawei after the Commerce Department’s action last month.

But it resumed sales about two weeks ago after Micron reviewed the entity list rules and “determined that we could lawfully resume” shipping a subset of products, Mr. Mehrotra said.

“However, there is considerable ongoing uncertainty around the Huawei situation,” he added.

A spokesman for the Commerce Department, in response to questions about the sales to Huawei, referred to a section of the official notice about the company being added to the entity list, including that the purpose was to “prevent activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States.”

A spokesman for the Commerce Department, in response to questions about the sales to Huawei, referred to a section of the official notice about the company being added to the entity list, including that the purpose was to “prevent activities contrary to the national security or foreign policy interests of the United States.”

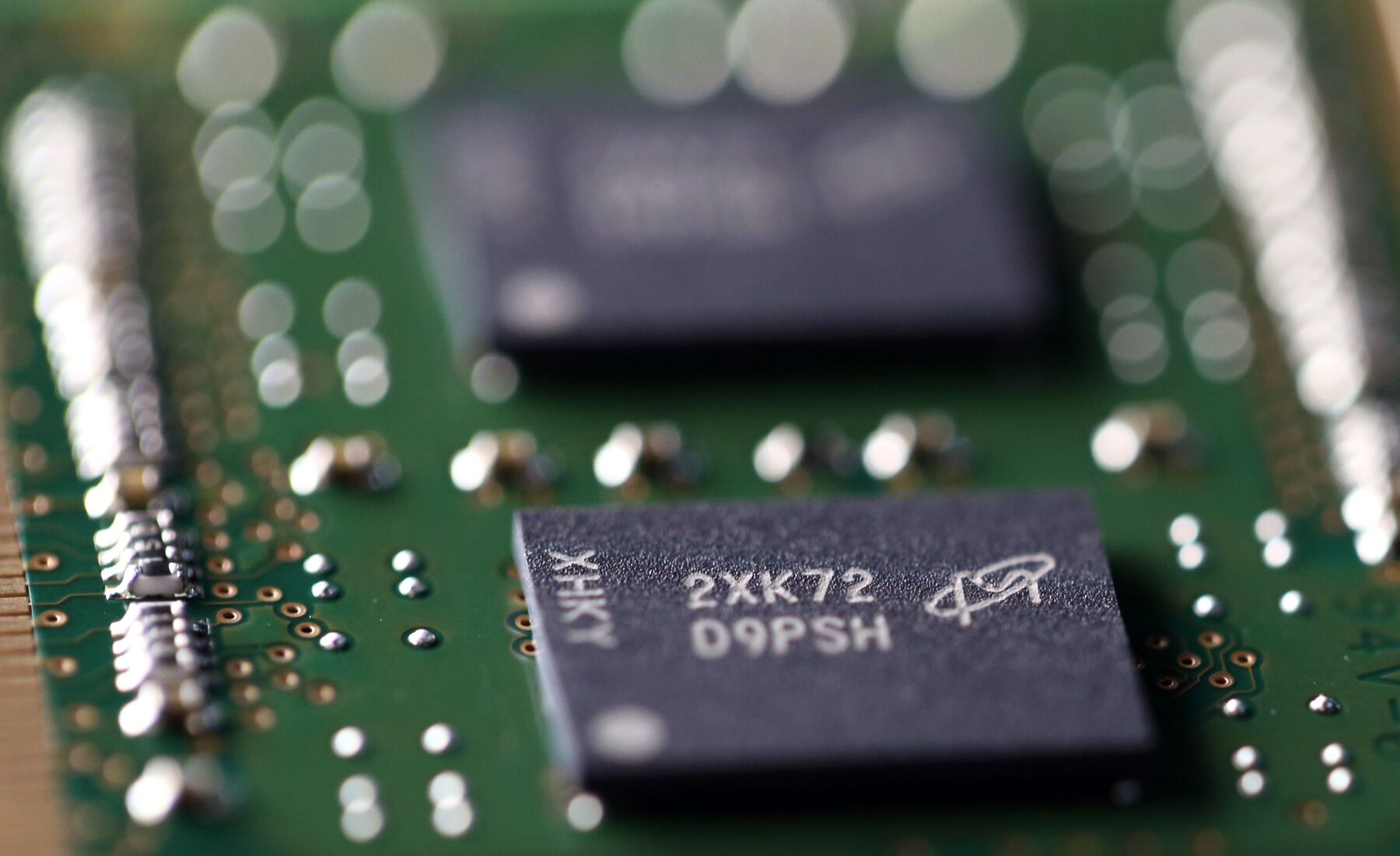

The Idaho-based Micron competes with South Korean companies like Samsung to supply memory chips that go into Huawei’s smartphones.

A senior administration official said that after the Commerce Department put Huawei on the entity list, the Semiconductor Industry Association sent a letter to the White House asking for waivers for some companies to allow them to continue selling components to Huawei.

But the administration did not grant the waivers, he said, and the companies then found what they assert is a legal basis for continuing their sales.

Administration officials would like to address this issue, he said, but they do not plan to do so before the G-20 summit in Japan at the end of this week.

Administration officials would like to address this issue, he said, but they do not plan to do so before the G-20 summit in Japan at the end of this week.

Mr. Trump’s top priority is to discuss the general trade dispute with Xi Jinping and get the two sides to resume trade talks that have dragged on since early 2018, the official said.

The fate of Huawei, a crown jewel of Chinese innovation and technological prowess, has become a symbol of the economic and security standoff between the United States and China.

The fate of Huawei, a crown jewel of Chinese innovation and technological prowess, has become a symbol of the economic and security standoff between the United States and China.

Chinese companies like Huawei, which makes telecom networking equipment, could intercept and secretly divert information to China.

Xi Jinping and President Trump are expected to have an “extended” talk this week during the Group of 20 meetings in Japan, a sign that the two countries are again seeking a compromise after trade discussions broke down in May.

After the talks stalled, the Trump administration announced new restrictions on Chinese technology companies.

Along with Huawei, the administration blocked a Chinese supercomputer maker from buying American tech, and it is considering adding the surveillance technology company Hikvision to the list.

Kevin Wolf, a former Commerce Department official and partner at the law firm Akin Gump, has advised several American technology companies that supply Huawei.

Kevin Wolf, a former Commerce Department official and partner at the law firm Akin Gump, has advised several American technology companies that supply Huawei.

He said he told executives that Huawei’s addition to the list did not prevent American suppliers from continuing sales, as long as the goods and services weren’t made in the United States.

The SK Hynix plant in Icheon, South Korea. American companies are worried about losing market share to foreign rivals.

A chip, for example, can still be supplied to Huawei if it is manufactured outside the United States and doesn’t contain technology that can pose national security risks.

The SK Hynix plant in Icheon, South Korea. American companies are worried about losing market share to foreign rivals.

A chip, for example, can still be supplied to Huawei if it is manufactured outside the United States and doesn’t contain technology that can pose national security risks.

But there are limits on sales from American companies.

If the chip maker provides services from the United States for troubleshooting or instruction on how to use the product, for example, the company would not be able to sell to Huawei even if the physical chip were made overseas, Wolf said.

“This is not a loophole or an interpretation because there is no ambiguity,” he said.

“This is not a loophole or an interpretation because there is no ambiguity,” he said.

“It’s just esoteric.”

After this article was published online on Tuesday, Garrett Marquis, the White House National Security Council spokesman, criticized the companies’ workarounds.

After this article was published online on Tuesday, Garrett Marquis, the White House National Security Council spokesman, criticized the companies’ workarounds.

He said, “If true, it’s disturbing that a former Senate-confirmed Commerce Department official, who was previously responsible for enforcement of U.S. export control laws including through entity list restrictions, may be assisting listed entities to circumvent those very enforcement mechanisms.”

Wolf said he does not represent Chinese companies or firms on the entity list, and he added that Commerce Department officials had provided him with identical information on the scope of the list in recent weeks.

In some cases, American companies aren’t the only source of important technology, but they want to avoid losing Huawei’s valuable business to a foreign rival.

Wolf said he does not represent Chinese companies or firms on the entity list, and he added that Commerce Department officials had provided him with identical information on the scope of the list in recent weeks.

In some cases, American companies aren’t the only source of important technology, but they want to avoid losing Huawei’s valuable business to a foreign rival.

For instance, the Idaho-based Micron competes with South Korean companies like Samsung and SK Hynix to supply memory chips that go into Huawei’s smartphones.

If Micron is unable to sell to Huawei, orders could easily be shifted to those rivals.

Beijing has also pressured American companies.

Beijing has also pressured American companies.

This month, the Chinese government said it would create an “unreliable entities list” to punish companies and individuals it perceived as damaging Chinese interests.

The following week, China’s chief economic planning agency summoned foreign executives, including representatives from Microsoft, Dell and Apple.

It warned them that cutting off sales to Chinese companies could lead to punishment and hinted that the companies should lobby the United States government to stop the bans.

The stakes are high for some of the American companies, like Apple, which relies on China for many sales and for much of its production.

A FedEx warehouse in Kernersville, N.C. “FedEx is a transportation company, not a law enforcement agency,” the company said in a complaint against the government.

Wolf said several companies had scrambled to figure out how to continue sales to Huawei, with some businesses considering a total shift of manufacturing and services of some products overseas.

A FedEx warehouse in Kernersville, N.C. “FedEx is a transportation company, not a law enforcement agency,” the company said in a complaint against the government.

Wolf said several companies had scrambled to figure out how to continue sales to Huawei, with some businesses considering a total shift of manufacturing and services of some products overseas.

The escalating trade battle between the United States and China is “causing companies to fundamentally rethink their supply chains,” he added.

That could mean that American companies shift their know-how, on top of production, outside the United States, where it would be less easy for the government to control, said Martin Chorzempa, a research fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

“American companies can move some things out of China if that’s problematic for their supply chain, but they can also move the tech development out of the U.S. if that becomes problematic,” he said.

That could mean that American companies shift their know-how, on top of production, outside the United States, where it would be less easy for the government to control, said Martin Chorzempa, a research fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

“American companies can move some things out of China if that’s problematic for their supply chain, but they can also move the tech development out of the U.S. if that becomes problematic,” he said.

“And China remains a large market.”

“Some of the big winners might be other countries,” Mr. Chorzempa said.

Some American companies have complained that complying with the tight restrictions is difficult or impossible, and will take a toll on their business.

On Monday, FedEx filed a lawsuit against the federal government, claiming that the Commerce Department’s rules placed an “impossible burden” on a company like FedEx to know the origin and technological makeup of all the shipments it handles.

FedEx’s complaint didn’t name Huawei specifically.

“Some of the big winners might be other countries,” Mr. Chorzempa said.

Some American companies have complained that complying with the tight restrictions is difficult or impossible, and will take a toll on their business.

On Monday, FedEx filed a lawsuit against the federal government, claiming that the Commerce Department’s rules placed an “impossible burden” on a company like FedEx to know the origin and technological makeup of all the shipments it handles.

FedEx’s complaint didn’t name Huawei specifically.

But it said that the agency’s rules that have prohibited exporting American technology to Chinese companies placed “an unreasonable burden on FedEx to police the millions of shipments that transit our network every day.”

“FedEx is a transportation company, not a law enforcement agency,” the company said.

A Commerce Department spokesman said it had not yet reviewed FedEx’s complaint but would defend the agency’s role in protecting national security.

“FedEx is a transportation company, not a law enforcement agency,” the company said.

A Commerce Department spokesman said it had not yet reviewed FedEx’s complaint but would defend the agency’s role in protecting national security.

An article of faith.

An article of faith.