The diplomat, Anna Lindstedt, arranged unauthorized talks between the daughter of a detained bookseller and two men representing Chinese interests.

By Iliana Magra and Chris Buckley

Sweden’s former ambassador to China has been charged with “arbitrariness during negotiations with a foreign power,” after she held what Swedish prosecutors said on Monday were unauthorized meetings with two men representing Chinese state interests.

The announcement of the charges was the latest twist in a four-year-old case, in which a Swedish citizen was spirited to China from Thailand, the ambassador held what the authorities say were secret meetings in a Stockholm hotel, and ties between China and Sweden have been strained.

The former ambassador, Anna Lindstedt, was accused earlier this year of arranging the talks between Angela Gui, the daughter of Gui Minhai, a Swedish bookseller detained in China, and two Chinese men who had offered to help free Mr. Gui in January.

Instead of talks about freeing her father, Ms. Gui was pressured to keep silent.

After the talks at a Stockholm hotel, Ms. Gui accused Lindstedt, the ambassador at the time, of arranging the talks without authorization from the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

After the talks at a Stockholm hotel, Ms. Gui accused Lindstedt, the ambassador at the time, of arranging the talks without authorization from the Swedish Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

The ministry opened an internal investigation into Lindstedt in mid-February.

Swedish Quisling Anna Lindstedt

Swedish Quisling Anna Lindstedt

“In this specific consular matter, she has exceeded her mandate and has therefore rendered herself criminally liable,” Hans Ihrman, the deputy chief public prosecutor for Sweden’s National Security Unit, said in a statement on Monday.

Mr. Ihrman said the charge of arbitrariness during negotiations with a foreign power was “unprecedented.”

“We have looked way back to find any kind of indictment for this, but in modern times we have no trail of an investigation,” he said in a telephone interview.

Mr. Ihrman described the meeting as an attempt by Chinese officials to stop Ms. Gui’s criticism of the Chinese government because of the treatment of her father.

“It’s about this daughter’s right to freedom of speech, which they have tried to act upon,” he said.

Nevertheless, he said, Lindstedt acted on her own without the necessary support or permission from the Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

The charge can bring a maximum prison sentence of two years under the Swedish Penal Code.

“We have looked way back to find any kind of indictment for this, but in modern times we have no trail of an investigation,” he said in a telephone interview.

Mr. Ihrman described the meeting as an attempt by Chinese officials to stop Ms. Gui’s criticism of the Chinese government because of the treatment of her father.

“It’s about this daughter’s right to freedom of speech, which they have tried to act upon,” he said.

Nevertheless, he said, Lindstedt acted on her own without the necessary support or permission from the Ministry for Foreign Affairs.

The charge can bring a maximum prison sentence of two years under the Swedish Penal Code.

A trial date for Lindstedt has not been set, Mr. Ihrman said.

The Swedish public broadcaster SVT reported Monday that prosecutors chose a milder charge than what the government’s security service had sought, “disloyalty when negotiating with a foreign power,” which carries up to a 10-year sentence.

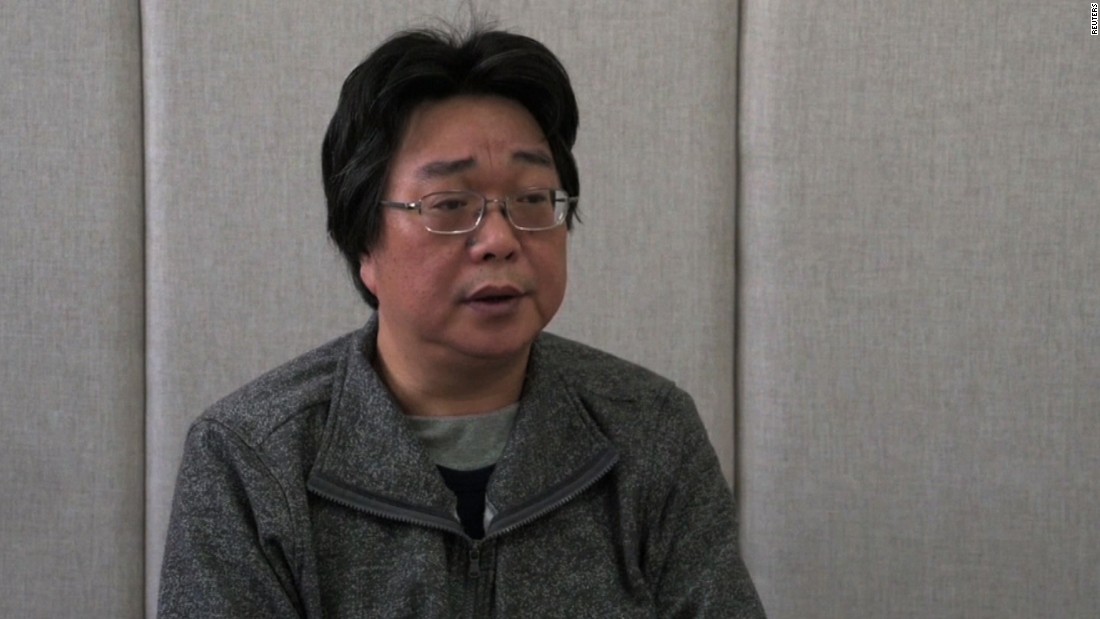

Mr. Gui was one of five Hong Kong-based publishers who were abducted and taken to China in 2015 after publishing books that were critical of the Communist Party elite, setting off international condemnation.

After being taken from Thailand to China in 2015, he was formally released two years later but was not allowed to leave the country.

Mr. Gui was again detained early last year, when two Swedish diplomats tried to accompany him on a train from Shanghai to Beijing, where they planned to take him into the Swedish Embassy.

After being taken from Thailand to China in 2015, he was formally released two years later but was not allowed to leave the country.

Mr. Gui was again detained early last year, when two Swedish diplomats tried to accompany him on a train from Shanghai to Beijing, where they planned to take him into the Swedish Embassy.

But Chinese police officers boarded the train and took him into custody.

They said later that Mr. Gui was suspected of illegally providing state secrets, but gave no details or evidence.

They said later that Mr. Gui was suspected of illegally providing state secrets, but gave no details or evidence.

Soon after, the Chinese authorities brought Mr. Gui before a group of reporters, and he told them that the Swedish diplomats had wanted to spirit him back to Sweden.

Mr. Ihrman, the Swedish prosecutor, said on Monday that Mr. Gui was in a Chinese prison.

Relations between Sweden and China have been strained since Gui Minhai was kidnapped in 2015, and tensions increased last month when the Swedish office of the writers’ group PEN said that it was awarding a literary prize to Mr. Gui.

Mr. Ihrman, the Swedish prosecutor, said on Monday that Mr. Gui was in a Chinese prison.

Relations between Sweden and China have been strained since Gui Minhai was kidnapped in 2015, and tensions increased last month when the Swedish office of the writers’ group PEN said that it was awarding a literary prize to Mr. Gui.

The prize is given annually to an author or publisher who is persecuted, threatened or living in exile.

Three days later, the Chinese Embassy in Stockholm called the prize a “farce” and threatened consequences if members of the Swedish government were to attend the award ceremony.

A week later, Amanda Lind, Sweden’s minister of culture, not only attended the ceremony but also awarded the prize, despite warnings from the Chinese ambassador that Ms. Lind and other government officials working in the area of culture would no longer be welcome in China.

Late last month, China appeared to follow through on its warning, with SVT reporting that two Swedish films had been banned from screenings in China.

Last week, after a seminar in Gothenburg, Sweden, on Swedish-Chinese relations, the Chinese ambassador to Sweden, Gui Congyou, told the newspaper Goteborgs-Posten that China would limit trade with Sweden because of its handling of the Gui Minhai case.

Three days later, the Chinese Embassy in Stockholm called the prize a “farce” and threatened consequences if members of the Swedish government were to attend the award ceremony.

A week later, Amanda Lind, Sweden’s minister of culture, not only attended the ceremony but also awarded the prize, despite warnings from the Chinese ambassador that Ms. Lind and other government officials working in the area of culture would no longer be welcome in China.

Late last month, China appeared to follow through on its warning, with SVT reporting that two Swedish films had been banned from screenings in China.

Last week, after a seminar in Gothenburg, Sweden, on Swedish-Chinese relations, the Chinese ambassador to Sweden, Gui Congyou, told the newspaper Goteborgs-Posten that China would limit trade with Sweden because of its handling of the Gui Minhai case.

Jesper Bengtsson, the chairman of Swedish PEN, said the organization was surprised by the “amazingly” strong response from China to this year’s award.

“Governments and regimes have often reacted but never with threats, and threatening to block ministers from visiting China, Mr. Bengtsson said in a telephone interview, adding that the Swedish culture minister always attends the award ceremony.

Previous prize recipients include Nasrin Sotoudeh, the Iranian human rights lawyer who is serving a 38-year prison sentence after being convicted of crimes against national security, and Dawit Isaak, a Swedish-Eritrean journalist who was arrested in Eritrea in 2001 on security charges and has been imprisoned without a trial ever since.

Previous prize recipients include Nasrin Sotoudeh, the Iranian human rights lawyer who is serving a 38-year prison sentence after being convicted of crimes against national security, and Dawit Isaak, a Swedish-Eritrean journalist who was arrested in Eritrea in 2001 on security charges and has been imprisoned without a trial ever since.