Diamond glass could make your phone’s screen nearly unbreakable—and the FBI enlisted its inventor after Huawei tried to steal his secrets.

By Erik Schatzker

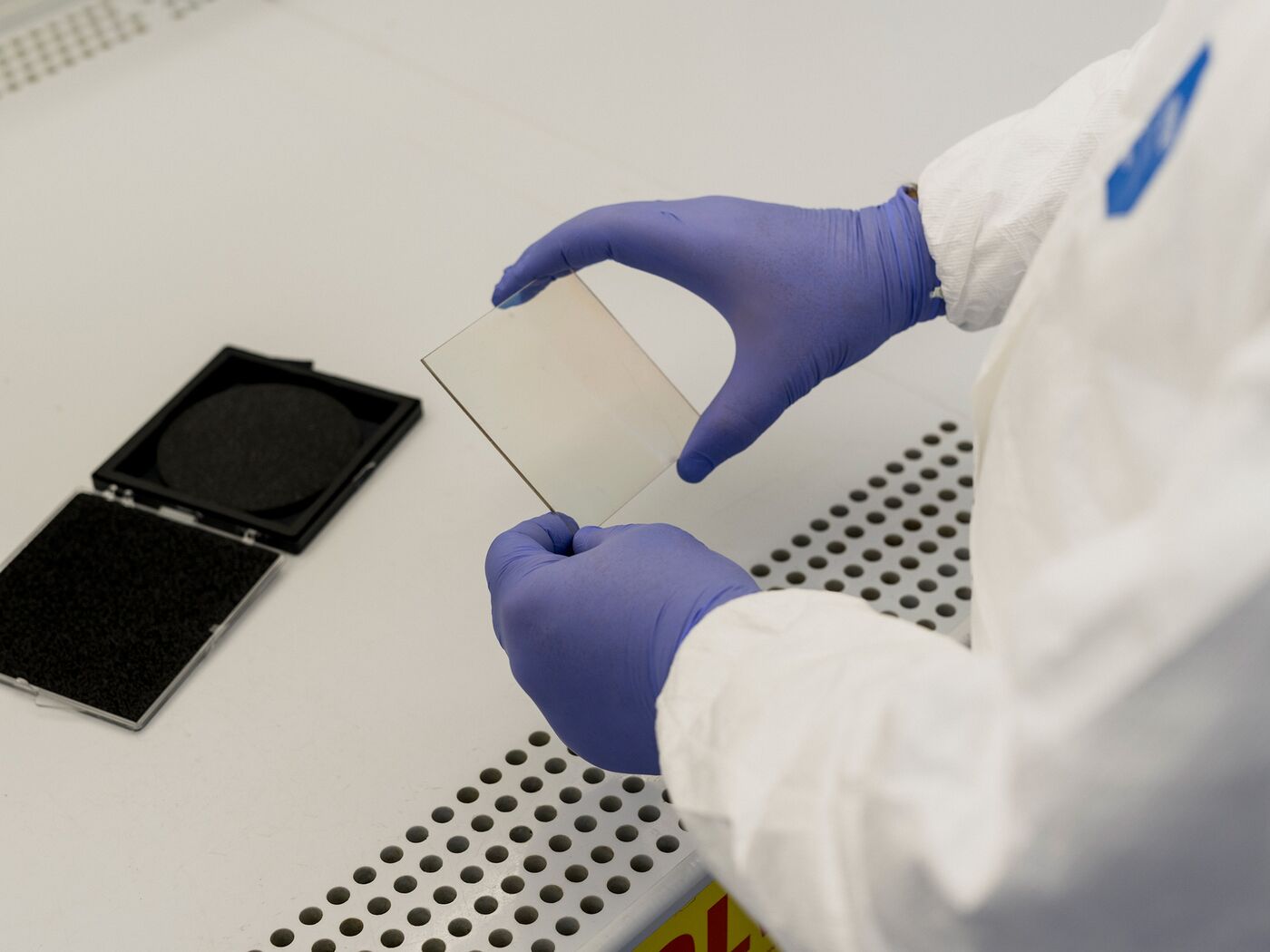

A prototype of Akhan Semiconductor’s Miraj Diamond Glass.

A prototype of Akhan Semiconductor’s Miraj Diamond Glass.

The sample looked like an ordinary piece of glass, 4 inches square and transparent on both sides.

It’d been packed like the precious specimen its inventor,

Adam Khan, believed it to be—placed on wax paper, nestled in a tray lined with silicon gel, enclosed in a plastic case, surrounded by air bags, sealed in a cardboard box—and then sent for testing to a laboratory in San Diego owned by

Huawei Technologies Co.

But when the sample came back last August, months late and badly damaged, Khan knew something was terribly wrong.

Was the Chinese company trying to steal his technology?

The glass was a prototype for what Khan’s company,

Akhan Semiconductor Inc., describes as a nearly indestructible smartphone screen.

Khan’s innovation was figuring out how to coat one side of the glass with a microthin layer of artificial diamond.

He hoped to license this technology to phone manufacturers, which could use it to develop an entirely new, superdurable generation of electronics.

“Lighter, thinner, faster, stronger,” says Khan, in full sales mode.

Miraj, he promises, will lead to a “fundamental next level in design.”

Miraj Diamond Glass at Akhan’s headquarters in Gurnee

Miraj Diamond Glass at Akhan’s headquarters in Gurnee

Like all inventors, Khan was paranoid about knockoffs.

Even so, he was caught by surprise when Huawei, a potential customer, began to behave suspiciously after receiving the meticulously packed sample.

Khan was more surprised when the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation drafted him and Akhan’s chief operations officer, Carl Shurboff, as participants in its investigation of Huawei.

The FBI asked them to travel to Las Vegas and conduct a meeting with Huawei representatives at last month’s Consumer Electronics Show.

Shurboff was outfitted with surveillance devices and recorded the conversation while a Bloomberg

Businessweek reporter watched from safe distance.

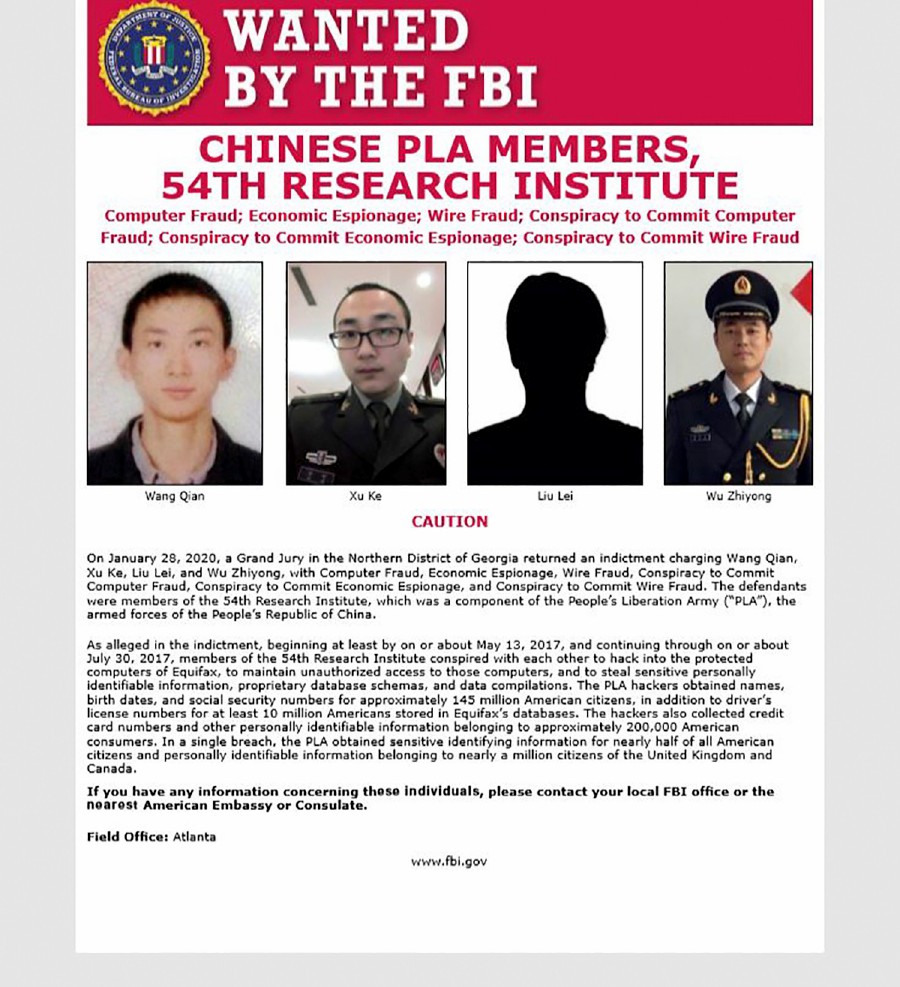

This investigation, which hasn’t previously been made public, is separate from the recently announced

grand jury indictments against Huawei.

On Jan. 28, federal prosecutors in Brooklyn

charged the company and its chief financial officer,

Meng Wanzhou, with multiple counts of fraud and conspiracy.

In a separate case, prosecutors in Seattle

charged Huawei with theft of trade secrets, conspiracy, and obstruction of justice, claiming that one of its employees stole a part from a robot, known as Tappy, at a

T-Mobile US Inc. facility in Bellevue, Wash.

“These charges lay bare Huawei’s blatant disregard for the laws of our country and standard global business practices,” Christopher Wray, the FBI director, said in a

press release accompanying the Jan. 28 indictments.

“Today should serve as a warning that we will not tolerate businesses that violate our laws, obstruct justice, or jeopardize national and economic well-being.”

Featured in Bloomberg

Featured in Bloomberg Businessweek

, Feb. 11, 2019.

If the new investigation bears fruit, it could, along with the indictments, bolster the Trump administration’s effort to block Huawei from selling equipment for fifth-generation, or

5G, wireless networks in the

U.S. and allied nations.

Huawei poses a national security threat because it could build undetectable backdoors into 5G hardware and software, allowing the Chinese government to spy on American communications and wage cyberwarfare.

On the same day Wray’s statement was released, the government searched the Huawei lab in San Diego where Akhan’s glass had been sent.

The FBI raid was a secret, but not to Khan and Shurboff, who’d been receiving regular briefings of the investigation’s progress through Akhan’s lawyer, Renato Mariotti, a well-known former prosecutor who’s now a partner at Thompson Coburn LLP.

By then, they’d succeeded in getting Huawei representatives to admit, on tape, to breaking the contract with Akhan and, evidently, to violating U.S. export-control laws.

Huawei did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

This story is based on documents—including emails and text messages exchanged among Huawei, Akhan, and the FBI—as well as reporting from the sting operation in Las Vegas and interviews with Khan and Shurboff.

Businessweek shared a detailed account of the investigation with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of New York, which declined to comment.

The FBI also declined to comment.

Khan’s work on diamond glass goes back to his college days, when he began learning about so-called nanodiamonds as a 19-year-old electrical engineering and physics student at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

After graduation, he ran experiments at the Stanford Nanofabrication Facility and teamed up with researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory, eventually developing and patenting a way to deposit a thin coating of tiny diamonds on materials such as glass.

He also licensed diamond-related patents for Akhan from the Argonne lab in 2014.

By the following year, Khan was confident enough to start promoting his new technology.

He joined the conference circuit, began giving interviews to trade publications, and hired Shurboff, who’d spent 25 years in various roles at

Motorola Inc.

It was time, Khan believed, to go to market.

Akhan founder and CEO Khan.

Akhan founder and CEO Khan.

In the smartphone world, extra-strong display glass is a competitive advantage, like a fast processor or a really good camera.

It’s been that way ever since Steve Jobs picked Corning to supply a screen for the first iPhone more than a decade ago.

Reviewers marveled that the device could be shoved into a pocket full of keys and coins and its then-giant display would come out unscathed.

To take on Corning, Akhan needed to convince the world’s big smartphone manufacturers—including Apple, Samsung, and Huawei—that its diamond-coated glass was even tougher than Gorilla Glass.

In 2016, Shurboff began sending out samples from Akhan’s production facility in Gurnee, Ill., a Chicago suburb.

He shipped the first one to

Samsung; another early sample went to Huawei.

Even then, before Trump’s trade war and the indictments, the Huawei name carried plenty of baggage.

Motorola said in a 2010 lawsuit that Huawei had successfully turned some of its Chinese-born employees into informants.

And in 2012 the U.S. House Intelligence Committee labeled Huawei a national security threat and urged the government and American businesses not to buy its products.

The Cisco and Motorola lawsuits ended with settlements.

Since 2012, under pressure from the government, the major U.S. telecommunications companies have essentially blacklisted Huawei, refusing to carry its smartphones or use its equipment in their networks.

But most of the world kept on buying from Huawei, choosing to ignore the allegations that the company has consistently denied.

At the same time, U.S. tech companies have remained free to sell parts to Huawei.

The sender was Angel Han, a Huawei engineer in San Diego.

In email exchanges and calls that followed, Han conveyed a sense of urgency.

In one email on Nov. 7, 2016, Han said Huawei was “actively looking for new technologies for our innovative product in this fast pace [sic] consumer electronics industry,” according to a copy reviewed by Businessweek.

“Vendor’s capability to move fast and deliver is also crucial for us.”

Reached on a mobile phone number that appeared on text messages exchanged with Akhan, a woman who identified herself as Angel Han denied knowing anyone at Akhan; then, when she was presented with specific details about interactions with Akhan, she said, “I can’t recall.”

Then she hung up.

Akhan COO Shurboff.

Akhan COO Shurboff.

By February 2017, the two companies had a deal.

Akhan would ship two samples of Miraj to Huawei in San Diego.

According to a letter of intent, signed by both parties, Huawei promised to return any samples within 60 days and also to limit any tests it might perform to methods that wouldn’t cause damage. (The latter provision is standard in the industry and is designed to make it hard to reverse-engineer any intellectual property.)

Shurboff noted in documents he sent to Han that Huawei had to comply with U.S. export laws, including provisions of the

International Traffic in Arms Regulations, or ITAR, which govern the export of materials with defense applications.

Diamond coatings are on the list because of their potential for use in laser weapons.

Khan and Shurboff decided early on that Akhan would license the first generation of its Miraj glass to a single handset maker, hoping the promise of exclusivity would give their startup some leverage. Huawei, Khan says, indicated it was eager to stay in the race, and on March 26, 2018, Akhan shipped an improved sample to Han.

“We were very optimistic,” Khan says.

“Having one of the top three smartphone manufacturers back you, at least on paper, is very attractive.”

The first sign of trouble came two months later, in May, when Huawei missed the deadline to return the sample.

Shurboff says his emails to Han requesting its immediate return were ignored.

The following month, Han wrote that Huawei had been performing “standard” tests on the sample and included a photo showing a big scratch on its surface.

Finally, a package from Huawei showed up at Gurnee on Aug. 2.

Shurboff remembers opening it.

It looked just like the package Akhan had sent months earlier.

Inside the cardboard box was the usual protective packaging—air bags, plastic case, gel insert, and wax paper.

But he could tell something was wrong when he picked up the case.

It rattled.

The unscratchable Miraj sample wasn’t just scratched; it was broken in two, and three shards of diamond glass were missing.

Shurboff says he knew there was no way the sample could have been damaged in shipping—all the pieces would still be there in the case.

Instead, he believed that Huawei had tried to cut through the sample to gauge the thickness of its diamond film and to figure out how Akhan had engineered it.

“My heart sank,” he says.

“I thought, ‘Great, this multibillion-dollar company is coming after our technology. What are we going to do now?’”

The packaging for Akhan’s Miraj Diamond Glass.

The packaging for Akhan’s Miraj Diamond Glass.

Shurboff’s first call was to Khan.

Then he went to the FBI, which had been cultivating relationships with even the smallest American tech companies as part of a crackdown on Chinese theft of intellectual property.

Eight months earlier, in January 2018, a male FBI special agent in Chicago had paid a visit to Akhan in Gurnee.

According to Shurboff, the agent told him that the bureau was hoping to educate local startups on cybercrime and security vulnerabilities and to encourage them to come forward with suspicious activity.

The FBI specifically was trying to gather intelligence on Chinese efforts to obtain U.S. technology, the agent told Shurboff.

The conversation stuck in Shurboff’s mind.

That August, two weeks after receiving the broken glass from Huawei, he drove down to the FBI’s Chicago field office, which was holding a seminar for area executives on corporate espionage. Shurboff watched as a female special agent discussed the case in which Huawei stole trade secrets from T-Mobile in 2012.

During a break, Shurboff approached the agent and told her what had happened to Akhan.

He mentioned that diamond coating was an ITAR-regulated material with defense applications and raised the possibility that the sample had been in the wrong hands.

In addition to its work on smartphone glass, Akhan had been adapting its diamond technology for semiconductors and the military.

Shurboff

Shurboff

To many, Shurboff’s story might have sounded far-fetched.

Not to the FBI.

“They took a very keen interest immediately and wanted to know more,” he says.

Things moved quickly.

The Akhan executives found themselves on regular conference calls with officials from the FBI and the U.S. Department of Justice.

Taking the lead on several of these calls was David Kessler, the assistant U.S. attorney in Brooklyn who, it turned out later, would prosecute Huawei’s CFO.

The two FBI agents picked up the broken sample in Gurnee and delivered it to the FBI’s research center in Quantico, Va.

When Khan and Shurboff joined the group on a subsequent call, an FBI expert in forensic gemology briefed them on his findings.

They recall the gemologist saying he’d analyzed the diamond glass sample and concluded that Huawei had blasted it with a 100-kilowatt laser, powerful enough to be used as a weapon.

Throughout the fall of 2018, the FBI agents asked Khan and Shurboff for emails, copies of non-disclosure agreements, letters of intent, shipping records, even the box Huawei used to return the sample that summer.

The FBI had another request, too: Would they re-establish contact with Angel Han, the Huawei engineer?

On Dec. 10, while the FBI listened in, Shurboff and Khan say they spoke to Han by phone, quizzing her about the broken sample of diamond glass.

What happened during the tests?

Why were shards missing?

Han told them she didn’t know, because the sample had been in China and was shipped directly to Akhan from there.

This was a criminal violation of ITAR rules, but Han didn’t seem to realize or care.

And instead of backing off, Han said Huawei wanted to continue talks about becoming Akhan’s first customer and proposed a face-to-face meeting a few weeks later at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas.

She even offered to bring along a senior Huawei official from Shenzhen.

Khan and Shurboff were flabbergasted.

It was hard to tell who was playing whom.

The Akhan executives arrived in Las Vegas on Tuesday, Jan. 8, and checked in at the Mandalay Bay Resort & Casino.

They’d arranged to meet Han and her colleague the following afternoon at 3 p.m.

If all went according to plan, that would be the sting.

The female FBI agent from Chicago, who’d flown in to oversee the operation, explained to Khan and Shurboff in text messages how it would work: The bureau was securing a room at the Las Vegas Convention Center, where the CES conference was taking place.

It would be bugged, so the FBI could listen in from another location in the building.

Shurboff brought signage to make it look like Akhan had rented the space.

At about noon on Jan. 9, the agent met with the Akhan executives and gave Shurboff three different covert recording devices to wear and carry as a backup plan.

Shurboff texted Han: “We have a nice quiet conference room right off the Grand Hall if you like to meet there.”

He noted it wasn’t far from the Huawei booth at CES.

But at 2 p.m., Han responded by text, saying that she was at the Venetian Casino and couldn’t leave for at least another hour.

That was a problem, because the FBI had the room for a limited time.

Shurboff told Han to stay at the Venetian.

He and Khan would meet her there.

They arrived just before 3 p.m. and texted Han a picture of their location, on the second floor of the Venetian by the escalator, right in front of Sin City Brewing.

Khan was casually dressed in a dark peacoat, black button-up shirt, gray pants, and sneakers. Shurboff’s attire was more businesslike: a light blue dress shirt, gray sports jacket, black trousers, and brand-new leather shoes.

Han showed up at 3:20 p.m. with a woman who introduced herself as Jennifer Lo, a senior supply manager with Huawei in Santa Clara, Calif. (The Shenzhen-based Huawei executive hadn’t come, they explained, because the company wasn’t allowing its senior Chinese executives to travel to the U.S.)

The four of them chatted briefly, walked toward the food court at the Venetian, and took seats around a table at a Prime Burger.

The Businessweek reporter watched from about 100 feet away, in front of a gelato stand.

Khan and Shurboff had expected to conduct the sting in the safety and quiet of the FBI’s room at CES.

Now, total rookies in the intelligence game, they had to remain calm while recording the conversation with Huawei in a noisy, crowded restaurant.

The hope had been that Lo, whom Khan guessed was in her early 40s, would have more to say about the destruction of Akhan’s sample and why Huawei was so interested in diamond film technology. Khan recalls her asking questions about the manufacturing capacity at Akhan’s pilot facility in Gurnee.

She acknowledged that the sample glass had been to China but disputed that this had been an ITAR violation.

Huawei had checked, and it was OK, she said.

There was some tension, and at one point, Lo startled Khan and Shurboff by wondering aloud if the U.S. government was monitoring their meeting.

As for the damaged sample, Lo, like Han, claimed ignorance.

She was there to make sure Huawei still had a shot at being the first company to put diamond glass on a smartphone.

If Akhan walked away, she said she might lose her job. (Reached on the mobile phone number on her Huawei business card, Lo confirmed her identity and said she was at CES to “meet with some suppliers.” When asked about the destruction of the sample and the shipment to China she said, “I’m not involved and cannot comment on this.”)

Over the next few days, Khan received an unsettling piece of news.

During the Prime Burger meeting, Shurboff had coincidentally run into representatives from another big potential customer for Miraj glass.

Feeling uneasy in his role as an FBI asset, he’d curtly brushed them off to return to the discussion with Huawei.

Now the other customer seemed concerned that Akhan was trying to start a bidding war.

Khan was determined not to lose a promising lead.

Previously, he’d asked Businessweek to withhold the details of the sting operation until the government moved to indict Huawei or arrest someone.

But, eager to explain the encounter at the Prime Burger and clear up any confusion, he’d changed his mind and decided to go public with Akhan’s story, as well as issue a

statement about its cooperation with the FBI.

“Akhan takes seriously any unlawful use of its technology,” an embargoed copy of the statement reads.

The company, “will continue to cooperate with law enforcement and work towards an expedient resolution to this matter.”

The FBI raided Huawei’s San Diego facility on the morning of Jan. 28.

That evening, the two special agents and Assistant U.S. Attorney Kessler briefed Khan and Shurboff by phone.

The agents described the scope of the search warrant in vague terms and instructed Khan and Shurboff to have no further contact with Huawei.

Khan and Shurboff don’t know how the story will end.

It’s possible that the government will conclude there aren’t grounds for an indictment against Huawei.

Prosecutors also could decide that what happened to Akhan isn’t serious enough to seek charges.

If that’s so, it raises a question about the broader U.S. crackdown on Huawei: Is it based on hard evidence of wrongdoing or driven by a desperation to catch the Chinese company doing something—anything—bad?

On the other hand, if the government does conclude that Akhan was attacked, that a Chinese multinational really did target a tiny Chicago company with no revenue and no customers (as of yet), it would show just how far and wide Huawei is willing to go to steal American trade secrets.

“I think they’re identifying technologies that are key to their road map and going after them no matter what the size or scale or status of the business,” Khan says.

“I wouldn’t say they’re discriminating.”

Sen. Rick Scott questions Department of Justice Inspector General Michael Horowitz during a Senate Committee On Homeland Security And Governmental Affairs.

Sen. Rick Scott questions Department of Justice Inspector General Michael Horowitz during a Senate Committee On Homeland Security And Governmental Affairs.

“How would you feel if you were a U.S. scientist sending your best idea to the government in a grant application, and someone ended up doing your project in China?” said Dr. Ross McKinney, chief scientific officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges.

“How would you feel if you were a U.S. scientist sending your best idea to the government in a grant application, and someone ended up doing your project in China?” said Dr. Ross McKinney, chief scientific officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges.