By Mihir Sharma

The western colony has become a police state.

The western colony has become a police state.

The western colony has become a police state.

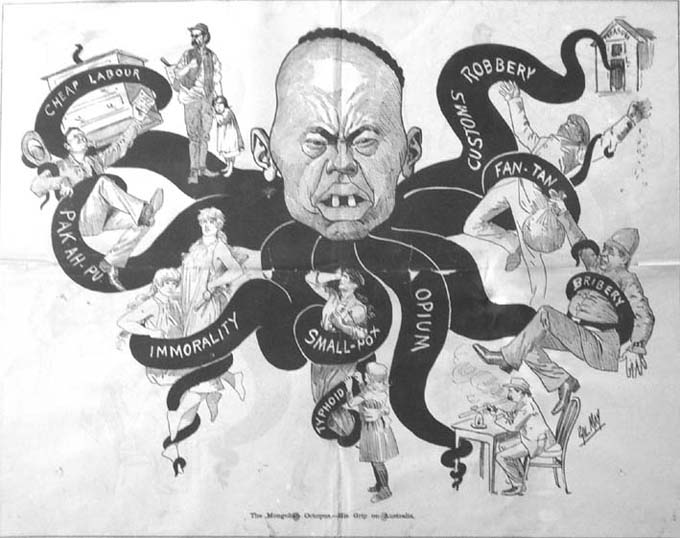

The western colony has become a police state. Nobody pretends the People’s Republic of China is a benign power, least of all its leaders in Beijing. Yet, even by the standards of what continues to be a horribly repressive state, the stories that are emerging from behind the Great Firewall about the crackdown on East Turkestan’s Uighur Muslim population are deeply disturbing and deserve more of the world’s attention.

The one country on earth which should best understand the danger and futility of such efforts has set up “reeducation centres” across the length and breadth of its largest colony, where political prisoners are instructed to repeat mantras about the greatness of the Chinese state and of its dictator Xi Jinping.

They write self-criticisms late into the night.

Observant Muslims are forced to drink alcohol.

Persistent dissenters are subject to torture, including in a terrifying device known as a “tiger chair.”

Persistent dissenters are subject to torture, including in a terrifying device known as a “tiger chair.”

One recent academic study warns that anything between several hundred thousand and over a million residents of East Turkestan may have been sent to the camps.

The Chinese government has repeatedly denied the existence of any reeducation camps, saying that the people of East Turkestan "live and work in peace and enjoy development and tranquillity.”

It has also argued in the past that the “tiger chair” is “padded for comfort.”

Now, you could be outraged by these stories and demand, as some countries have done, that Chinese leaders respect the human rights of all their citizens.

Now, you could be outraged by these stories and demand, as some countries have done, that Chinese leaders respect the human rights of all their citizens.

But fewer and fewer governments want to take the risk of offending China.

And, after all, more than half the people of East Turkestan are Muslims – and who today would really go out on a limb and speak out against the “reeducation” of faithful Muslims?

So in East Turkestan, as in Tibet, the world is likely to give China a pass.

But there’s another question that Chinese leaders, and the rest of us, should be asking.

But there’s another question that Chinese leaders, and the rest of us, should be asking.

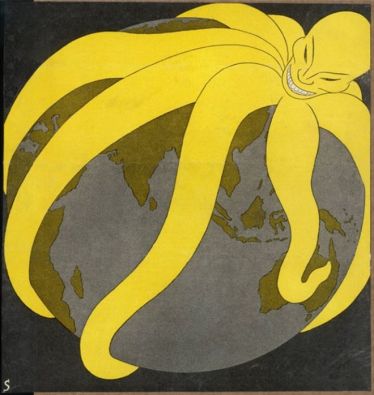

And that is: What does this repression mean for China’s ambitions in Central Asia and beyond?

After all, East Turkestan may today be a distant border colony.

After all, East Turkestan may today be a distant border colony.

But it occupies a very different position on the map of the world as Xi would remake it.

The Silk Roads of the past went through East Turkestan and, if the Belt and Road Initiative ever takes off, it is East Turkestan that will be its hub and heart.

The Chinese colony is intended to connect Central Asia, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and Siberia to the densely industrialized Chinese heartland.

China’s crackdown is meant at least in part to pacify the region, which has seen fluctuating waves of resentment and separatist sentiment over the years.

China’s crackdown is meant at least in part to pacify the region, which has seen fluctuating waves of resentment and separatist sentiment over the years.

But can a colony so tightly controlled by the authorities become the crossroads of a continent’s trade?

Uighurs are now forbidden to travel abroad – and even those who leave the province for other parts of China are suspect.

Uighurs are now forbidden to travel abroad – and even those who leave the province for other parts of China are suspect.

Visa requirements for visitors from places like Pakistan have been tightened.

Fewer will visit; others have found that wives and children across the border have vanished into camps.

Trade is more than a few sealed trucks rolling up to a checkpoint set amid walls and barbed wire. Trade cannot happen without people – without the coming and going of traders, without bustling border cities and entrepots where deals are made and demand is weighed.

Perhaps China’s planners imagine that East Turkestan need be nothing but usefully located real estate, a barren land through which trains will thunder, shipping their products west.

Trade is more than a few sealed trucks rolling up to a checkpoint set amid walls and barbed wire. Trade cannot happen without people – without the coming and going of traders, without bustling border cities and entrepots where deals are made and demand is weighed.

Perhaps China’s planners imagine that East Turkestan need be nothing but usefully located real estate, a barren land through which trains will thunder, shipping their products west.

That is, however, unlikely to happen.

For one, East Turkestan does not stand in isolation.

Many of its people are part of a larger Central Asian cultural network.

The case of an ethnically Kazakh Chinese woman who fled after working in one of the camps, for instance, has become a cause célèbre in Kazakhstan.

The government in Astana is already having to deal with increasing popular anger about the East Turkestan crackdown and is quietly complaining to China.

The government in Astana is already having to deal with increasing popular anger about the East Turkestan crackdown and is quietly complaining to China.

The louder the discontent at home, the less polite its complaints will be.

Do Chinese leaders imagine that the Belt and Road can be laid down without the cooperation of Central Asia’s governments or of its people?

Perhaps China imagines instead that continued mass settlement of the colony by ethnically Han Chinese migrants from elsewhere in the country will solve the problem.

Perhaps China imagines instead that continued mass settlement of the colony by ethnically Han Chinese migrants from elsewhere in the country will solve the problem.

The government has, after all, ensured that the colony’s residency rules are the most liberal in China.

But that will merely create a social tinderbox that no “smart” police state, such as is being piloted in East Turkestan’s cities, can truly control.

It’s not yet too late for China to realize its errors and to seek reconciliation with East Turkestan’s Uighurs.

It’s not yet too late for China to realize its errors and to seek reconciliation with East Turkestan’s Uighurs.

If the land-based economic corridors of Xi’s imagination are to become a reality, then China will need to build a peaceful and secure East Turkestan that’s integrated effectively with its neighbors.

A police state full of brutal reeducation camps will merely provoke a terrifying backlash – and the Belt and Road will be among the casualties.

In this Dec. 22, 2017, photo, a Pakistani police officer stands guard at the site of Pakistan China Silk Road in Haripur, Pakistan. From Pakistan to Tanzania to Hungary, projects under Xi Jinping's signature "Belt and Road Initiative" are being canceled, renegotiated or delayed.

In this Dec. 22, 2017, photo, a Pakistani police officer stands guard at the site of Pakistan China Silk Road in Haripur, Pakistan. From Pakistan to Tanzania to Hungary, projects under Xi Jinping's signature "Belt and Road Initiative" are being canceled, renegotiated or delayed.  In this Dec. 22, 2017, photo, a Pakistani motorcyclist drives on a newly built Pakistan China Silk Road in Haripur, Pakistan.

In this Dec. 22, 2017, photo, a Pakistani motorcyclist drives on a newly built Pakistan China Silk Road in Haripur, Pakistan. A general view of Gwadar port in Gwadar, Pakistan Oct. 4, 2017. The port is at the heart of the $50 billion Chinese investment in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

A general view of Gwadar port in Gwadar, Pakistan Oct. 4, 2017. The port is at the heart of the $50 billion Chinese investment in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).