What's behind the India-China border stand-off?

BBC News

India and China have a long history of border disputes

India and China have a long history of border disputes

For four weeks, India and China have been involved in a stand-off along part of their 3,500km (2,174-mile) shared border.

The two nations fought a war over the border in 1962 and disputes remain unresolved in several areas, causing tensions to rise from time to time.

Since this confrontation began last month, each side has reinforced its troops and called on the other to back down.

How did the row begin?

It erupted when India opposed China's attempt to extend a border road through a plateau known as Doklam.

The plateau, which lies at a junction between China, the north-eastern Indian state of Sikkim and Bhutan, is currently disputed between Beijing and Thimphu.

India supports Bhutan's claim over it.

India is concerned that if the road is completed, it will give China greater access to India's strategically vulnerable "chicken's neck", a 20km (12-mile) wide corridor that links the seven north-eastern states to the Indian mainland.

Indian military officials told regional analyst

Subir Bhaumik that they protested and stopped the road-building group, which led Chinese troops to rush Indian positions and smash two bunkers at the nearby Lalten outpost.

"We did not open fire, our boys just created a human wall and stopped the Chinese from any further incursion," a brigadier said on condition of anonymity because he was not authorised to speak to the press.

Chinese officials say that in opposing the road construction, Indian border guards obstructed "normal activities" on the Chinese side, and called on India to immediately withdraw.

What is the situation now?

Both India and China have rushed more troops to the border region, and media reports say the two sides are in an "eyeball to eyeball" stand-off.

The Chinese ambassador to India

Luo Zhaohui told Press Trust of India news agency on Tuesday that India had to "unconditionally pull back troops" for peace to prevail.

The statement is being seen as a diplomatic escalation by China.

China also retaliated by stopping 57 Indian pilgrims who were on their way to the Manas Sarovar Lake in Tibet via the Nathu La pass in Sikkim.

The lake is a holy Hindu site and there is a formal agreement between the neighbours to allow devotees to visit.

Bhutan, meanwhile, has asked China to stop building the road, saying it is in violation of an agreement between the two countries.

What does India say?

Indian military experts say Sikkim is the only area through which India could make an offensive response to a Chinese incursion, and the only stretch of the Himalayan frontier where Indian troops have a terrain and tactical advantage.

They have higher ground, and the Chinese positions there are squeezed between India and Bhutan.

India and China fought a bitter war in 1962.

India and China fought a bitter war in 1962.

"The Chinese know this and so they are always trying to undo our advantage there," retired Maj-Gen

Gaganjit Singh, who commanded troops on the border, told the BBC.

Last week, the foreign ministry said that the construction "would represent a significant change of status quo with serious security implications for India".

Indian Defence Minister

Arun Jaitley also warned that the India of 2017 was not the India of 1962, and the country was well within its rights to defend its territorial integrity.

What does China say?

China has reiterated its sovereignty over the area, saying that the road is in its territory and accusing Indian troops of "trespassing".

It said India would do well to remember its defeat in the 1962 war, warning Delhi that China was also more powerful than it was then.

On Monday, a Chinese foreign ministry spokesman said that the border in Sikkim had been settled in an 1890 agreement with the British, and that India's violation of this was "very serious".

The

Global Times newspaper, meanwhile, accused India of undermining Bhutan's sovereignty by interfering in the road project, although Bhutan has since asked China to stop construction.

What's Bhutan's role in this?

Bhutan's Ambassador to Delhi

Vetsop Namgyel says China's road construction is "in violation of an agreement between the two countries".

Bhutan and China do not have formal relations but maintain contact through their missions in Delhi.

An Indian soldier on the China border.

An Indian soldier on the China border.

Security analyst

Jaideep Saikia told the BBC that Beijing had for a while now been trying to deal directly with Thimphu, which is Delhi's closest ally in South Asia.

"By raising the issue of Bhutan's sovereignty, they are trying to force Thimphu to turn to Beijing the way Nepal has," he said.

What next?

The region saw clashes between China and India in 1967, and tensions still flare occasionally. Commentators say the latest development appears to be one of the most serious escalations in recent years.

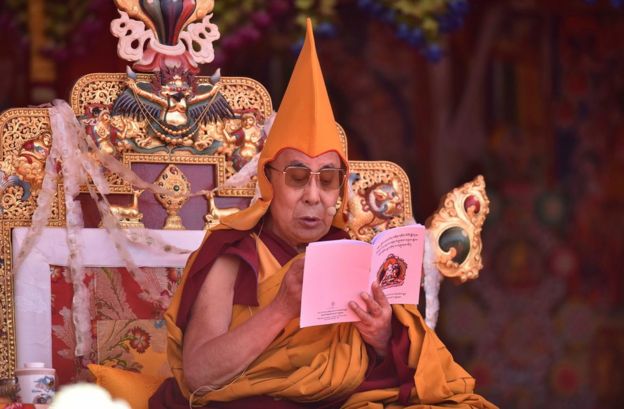

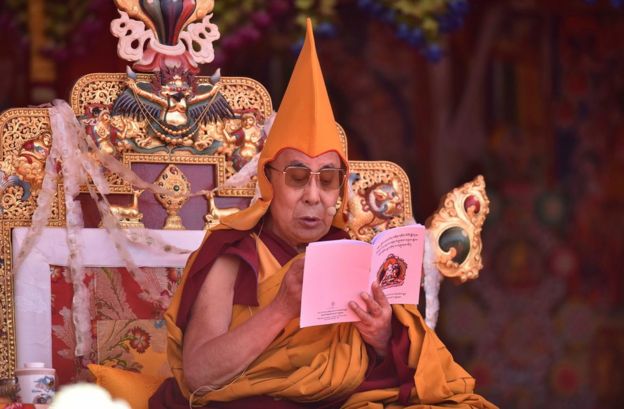

The fact that Tibet's spiritual leader, the

Dalai Lama resides in India has also been a sticking point between the two countries.

This stand-off in fact, comes within weeks of China's furious protests against the Dalai Lama's visit to

Arunachal Pradesh, an Indian state that China claims and describes as its own.

China recently protested against Tibetan spiritual leader Dalai Lama's visit to Arunachal Pradesh, an Indian state Beijing claims as its own.

China recently protested against Tibetan spiritual leader Dalai Lama's visit to Arunachal Pradesh, an Indian state Beijing claims as its own.