Beijing is seeking to win influence by meddling in the island’s elections

By Kathrin Hille in Tainan

Officially, Lu Aihua retired from politics eight years ago.

But as the campaign for Taiwan’s local elections on Saturday reached fever pitch last week, Lu received a visit from government investigators who are probing whether he is helping China interfere in the upcoming polls.

“The investigators are asking if the money the Chinese Communists are paying me comes with instructions to back a particular candidate or a particular party in the election,” says Lu, an influential former lawmaker in the southern city of Tainan.

China claims Taiwan as part of its territory and threatens to invade if the island insists on keeping its independence indefinitely.

Since the pro-independence Democratic Progressive party (DPP) won the presidency and a parliamentary majority in 2016, Beijing has ramped up pressure against Taipei on all fronts: military posturing, poaching its diplomatic allies, pushing airlines and hotels to refer to Taiwan as part of China, drastically cutting tour groups to the island and reducing agricultural imports from DPP strongholds.

Now, Beijing is trying to meddle from within as the island’s voters prepare to pick mayors, regional and local lawmakers, as well as borough wardens and village heads.

China is seeking to corrode Taiwan’s body politic through infiltration and disinformation — an action that echoes the growing debate in a number of western countries over attempts by China to weaken democratic governments.

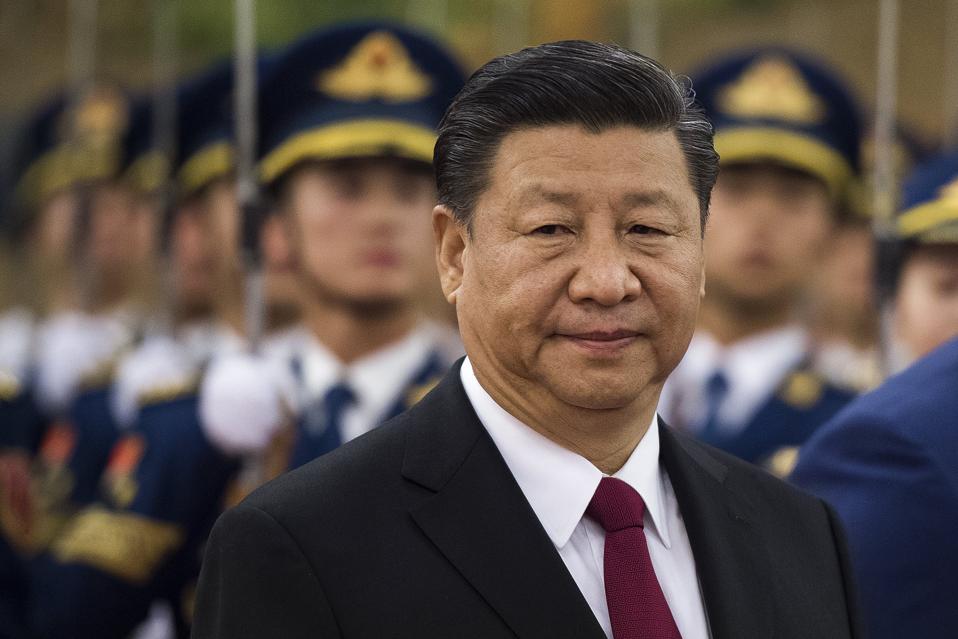

Lu Aihua, a former lawmaker who is a power broker in Tainan, shows a photograph of himself with the Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi, from 2012 when Wang was head of China's Taiwan affairs office.

“You have started noticing such tactics in the west since Donald Trump was elected [US president] and since Russia meddled in the US election — you even have a new term for it: ‘sharp power’,” says Chiu Chui-cheng, deputy minister of the Mainland Affairs Council, Taiwan’s cabinet level agency for relations with China.

“Nobody knows better about sharp power than we do — we are at the front lines!”

Although Saturday’s election will focus on local issues, politicians and experts say it is likely to predetermine the future of cross-Strait relations because a DPP defeat could block the road to re-election in 2020 for President Tsai Ing-wen, the prime target of Beijing’s wrath.

Foreign diplomats in Taipei say any indications of Beijing meddling in this week’s polls are noteworthy for western democracies grappling with the question of how to deal with a China that is openly challenging the norms and values established by the democratic west.

Washington this year for the first time accused China of meddling in US elections.

In Australia, debate is growing over Chinese interference in academic teaching and research.

New Zealand has had scandals over MPs’ links with Chinese Communist party organisations.

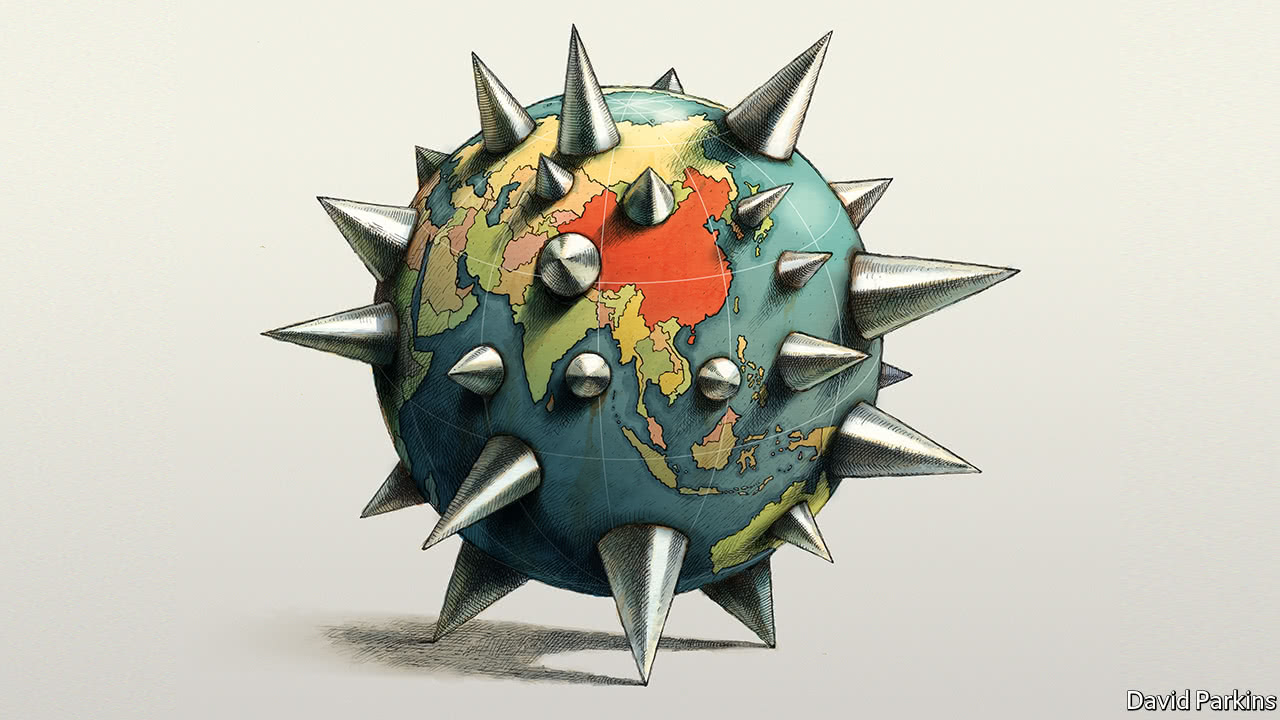

Against this backdrop, researchers from the National Endowment for Democracy coined the term sharp power, which Taiwan is identifying as an exact description of its problem.

In a paper published in 2017, they argued that influence wielded by Beijing and Moscow through the media, culture, think-tanks and academia should not be confused with soft power.

The influence of China and Russia can “pierce, penetrate or perforate the political and information environments in the targeted countries,” they wrote.

“Sharp power enables the authoritarians to cut into the fabric of a society, stoking and amplifying existing divisions. Russia has been especially adept at exploiting rifts within democracies.”

China has made no secret of its intention to do just that to Taiwan.

In an editorial in December 2016, months after the DPP’s victory, the Global Times, a nationalist tabloid owned by the Communist party’s mouthpiece People’s Daily, wrote in an editorial: “We will Lebanonise Taiwan if necessary,” suggesting that China could turn opposing ethnic, political and social groups inside Taiwan against each other as has happened in the Middle Eastern country.

“Many people have been focusing on China boasting that their fighter jets are circling our airspace and that their aircraft carrier is sailing through the Taiwan Strait. But that is not what worries me most,” says a senior Taiwanese national security official.

“What worries me most is infiltration and manipulation. You may call it sharp power, or you could just call it political warfare, or United Front work.”

Taiwan has been the target of United Front tactics — the art of influencing and manipulating adversaries going back decades — from Beijing ever since the Kuomintang (KMT) fled to Taiwan in 1949 after losing the Chinese civil war, dragging the island, which had until only four years earlier been a Japanese colony, into conflict with the Chinese Communist party.

But Beijing’s tactics are changing.

Xi Jinping’s predecessor, Hu Jintao tried to build relations with the KMT, wooing Taiwanese investors in China, and seeking to lure the island’s population of 23m with closer economic ties.

But the radical rejection of closer relations with China by Taiwan’s young generation in the 2014 Sunflower protests and the DPP’s subsequent landslide election victory two years later marked a failure of Hu’s policy.

China has since tweaked its approach, replacing macro policies with measures to target narrow groups or even individuals.

A former senior official with oversight of the Investigation Bureau, Taiwan’s FBI equivalent, says the bureau is observing a shift in Chinese infiltration.

“They are no longer betting on Taiwanese businessmen in the mainland, and they are no longer relying on the KMT. They are actively working on cultivating their own people here,” he says.

“They are reaching deep down to the grassroots of our society, and into the power base of the DPP.”

President Tsai Ing-wen at a ceremony to commission two new frigates into the Taiwan navy earlier this month.

That is where Lu comes in.

A tanned, wiry man with a 40-year career in the KMT under his belt, Lu is a “pillar”, or zhuangjiao in Mandarin — a grassroots power broker.

For local employers, temple community leaders, farmers’ and fishermen’s associations’ executives or even organised crime figures who help parties or individual politicians win elections, the zhuangjiao are a remnant of the KMT’s more than 40 years of authoritarian rule, which later became a tool for politicians across the spectrum when Taiwan democratised in the early 1990s.

With tactics ranging from friendly neighbourhood chats, to backroom deals, to mobilisation and outright vote buying, they are part of the soft underbelly of Taiwan’s raucous politics.

DPP officials say these traditional political structures were an easy target for exploitation by China.

“I have run election campaigns and I know how it works. Money changes hands but people tell you ‘I don’t want a receipt’”, says the former senior official with oversight of the Investigation Bureau.

“Our campaign finance accounting system is hollow, it doesn’t catch this kind of thing going on at the grassroots level.”

Taipei city mayoral candidate Yao Wen-chih of the DPP speaks to supporters at a campaign rally.

According to political analysts, Taiwan’s zhuangjiao are less powerful than they were 20 years ago. But they still voice concern that they offer an opening for Chinese sharp power.

“The population is urbanising, and it’s getting ever more difficult to mobilise and buy votes through traditional patron-client systems, and this trend continued all the way through 2016, with the KMT and the old forces being squeezed out,” says Lin Thung-hong, a researcher who looks at the Chinese impact on Taiwanese society at Academia Sinica, the country’s top academic research institution. “During this election, it’s crucial for us to find out whether this patron-client system has been brought under the control of a new patron, if it has been inherited by the Chinese Communist party.”

Lu dismisses the idea that he could possibly buy votes or finance a campaign on behalf of a Chinese master, but he does openly push Beijing’s case.

Over the past seven years, he has sold agricultural products from Tainan — a DPP stronghold — to the government of Zhuhai, a city in the Pearl River Delta.

He admits that Chinese officials have asked him to inform them when he expected the price of certain Taiwanese agricultural produce to drop, so they could step in and buy it.

While the government in Taipei says Beijing cut agricultural imports from southern Taiwan to punish the DPP’s voters after the 2016 result, Lu claims the opposite.

“China is very willing to help us, this little brother of theirs, but it is Taiwan itself that is rejecting them for political reasons,” he says.

Both farmers and fishermen in rural southern Tainan complain about a contracting market for their produce.

“Things are terrible,” says Tao Langyi, who farms milkfish near Tainan.

“The Chinese bought our fish on contract for three years in a row, but that stopped in 2016. It’s very hard for us now.”

Government officials accuse Beijing of exploiting real economic problems and creating fake ones with disinformation campaigns via Line, the messaging app popular in Taiwan.

“What they are doing is very similar to what the Russians did in America,” says the senior national security official.

“In the US, the deprived white population of the rust belt were easy prey. Here, it’s our Tainan farmers and fishermen.”

Polls suggest that sentiment is turning more broadly against the DPP with disappointment spreading among Taiwan’s notoriously fickle voters over the government’s record on issues from air pollution to gay marriage.

The Taiwanese Public Opinion Foundation, an independent research organisation, last week reported that only 23.5 per cent of voters identified themselves as DPP supporters while 35.4 per cent said they identified with the KMT and 36 per cent described themselves as independent — a radical shift from the DPP’s all-out victory two years ago.

Analysts caution, however, against interpreting this swing as a sign that the Taiwanese are moving to embrace China.

According to Academia Sinica, attitudes towards Beijing have barely shifted, with those identifying as Taiwanese or both Taiwanese and Chinese still far outnumbering those identifying as Chinese.

Local warden for the DPP Li Fu-hsiang waves to residents of his borough in Tainan

While government investigators are asking questions about Lu’s pineapple and fish diplomacy, their probe was actually triggered by another incident: In January, he convinced Li Fu-hsiang, a borough warden for the DPP in Yongkang, to bring two dozen borough wardens to Zhuhai hosted by officials from the Taiwan Affairs Office and the United Front Work department, the Communist party section in charge of foreign influencing operations.

The trip led to an outcry in the DPP.

“From this you can see how deep China’s hands are reaching into our elections,” says Lin Yi-chin, a DPP city councillor in Tainan who is campaigning for re-election.

“But it is so hard to do something about it. People love money — that Li Fu-hsiang supports me in the election doesn’t mean that he can’t be cheap and greedy.”

Such internal conflict in the DPP is part of Beijing’s calculus.

“In a solidly green [DPP] constituency like Tainan, they can’t hope to turn people to the KMT, but they can aim at sowing discord within the DPP,” says Academia Sinica’s Mr Lin.

Both Lu and Li dismiss the idea of improper conduct.

Lu justified the trip saying that it had helped Tainan local officials engage with Chinese counterparts and convinced them that China could be the solution to local economic problems caused, he says, by the DPP’s aversion to Beijing.

Li denies there were any serious discussions in Zhuhai, and says: “It was just a fun trip, just tourism.”

‘No hope’ candidate stirs mayoral contest

When Han Kuo-yu announced seven months ago that he was running for mayor in Kaohsiung, Taiwan’s second-largest municipality, few took notice.

His political career had been going nowhere since he lost his legislator’s seat in 2001.

His own party, the opposition KMT, agreed to his candidacy only because it considered challenging the Democratic Progressive party, which has governed in the port city for 20 years, a lost cause.

But with three days to go until the election, several Taiwanese media polls have Han leading the DPP incumbent.

The 61-year-old is offering a cocktail of populist and sometimes outlandish policies: he promises to transform Kaohsiung’s ageing industrial economy into an innovative powerhouse; help everyone “make a fortune”; more than double its population to 5m; and proposes to drill for oil on Taiping, an island in the South China Sea claimed by several countries but controlled by Taiwan.

While Han, was treated like a clown when peddling such ideas earlier in the campaign, he has rocketed to stardom over the past three months.

His campaign rallies have become carnival-like events.

His main event on Saturday attracted 80,000 people according to the police, rivalling that of the DPP mayor on the same day.

DPP campaign strategists and some independent observers see the astonishing turnround as a product of Chinese manipulation.

In a highly unusual pattern, the candidate’s name has been ranking much higher in internet searches in some Chinese provinces — where ordinary people rarely know individual Taiwanese politicians — than in Taiwan in recent weeks.

Moreover, Taiwanese TV channels, backed by pro-China businessmen, have been broadcasting features and talk shows with breathless primetime coverage of Han.

The candidate’s victory is far from certain — Taiwanese election polls are notoriously unreliable.

But Han has already shaken up the country’s politics.

Affichage des articles dont le libellé est sharp power. Afficher tous les articles

Affichage des articles dont le libellé est sharp power. Afficher tous les articles

mercredi 21 novembre 2018

lundi 19 novembre 2018

Rogue Nation

China hoped for a sharp power win at APEC, instead Xi Jinping left dissatisfied

By John Lee

With the presidents of the United States and Russia staying home, it seemed Chinese dictator Xi Jinping would dominate this weekend at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit and increase his country's influence in the Pacific.

China has already lent at least $1.3 billion to the Pacific Islands and about $590 million alone to the summit's host, Papua New Guinea (PNG).

For the first time in APEC's 25-year history, PNG was forced to end the summit with leaders failing to agree on a communique.

By John Lee

With the presidents of the United States and Russia staying home, it seemed Chinese dictator Xi Jinping would dominate this weekend at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit and increase his country's influence in the Pacific.

China has already lent at least $1.3 billion to the Pacific Islands and about $590 million alone to the summit's host, Papua New Guinea (PNG).

And to coincide with the PNG visit, Beijing promised $4 billion of finance to build PNG's first national road network, one of several gestures for which China secured effusive praise from Pacific Island countries including Samoa, Vanuatu, the Cook Islands, Tonga, Niue, Fiji and the President of the Federated States of Micronesia.

But nevertheless, Xi left PNG dissatisfied and disgruntled.

Xi Jinping says no one wins in 'cold war,' but Pence won't back down

Xi Jinping says no one wins in 'cold war,' but Pence won't back down

But nevertheless, Xi left PNG dissatisfied and disgruntled.

Xi Jinping says no one wins in 'cold war,' but Pence won't back down

Xi Jinping says no one wins in 'cold war,' but Pence won't back downFor the first time in APEC's 25-year history, PNG was forced to end the summit with leaders failing to agree on a communique.

And Beijing was also left embarrassed by reports of four Chinese officials being unceremoniously banished from the office of PNG Foreign Minister Rimbink Pato after trying to influence his statement.

For China, the trade summit should have been a public relations victory -- but it was turned into partial defeat when Chinese officials barred most reporters from participant countries and other international outlets from the forum and instead only allowed Chinese state-owned media journalists, citing space and security concerns according to Reuters.

Concerted and coordinated push back by the US and its allies

Of more enduring consequence than diplomatic embarrassment, is the concerted and coordinated push back by the US and its allies -- such as Japan and Australia -- which was done in a very public way.

For China, the trade summit should have been a public relations victory -- but it was turned into partial defeat when Chinese officials barred most reporters from participant countries and other international outlets from the forum and instead only allowed Chinese state-owned media journalists, citing space and security concerns according to Reuters.

Concerted and coordinated push back by the US and its allies

Of more enduring consequence than diplomatic embarrassment, is the concerted and coordinated push back by the US and its allies -- such as Japan and Australia -- which was done in a very public way.

Earlier this month, Australia announced a $2.2 billion "step-up to the Pacific" -- which includes an Australian Infrastructure Financing Facility and an export credit agency to help Australian companies invest in the region.

Then on Saturday, the Trilateral Partnership countries of the US, Japan and Australia released a joint statement declaring together they would identify infrastructure projects for development and financing.

Then on Saturday, the Trilateral Partnership countries of the US, Japan and Australia released a joint statement declaring together they would identify infrastructure projects for development and financing.

Pointedly, these projects would adhere to "international standards and principles for development, including openness, transparency, and fiscal sustainability."

That approach, it said, would "help to meet the region's genuine needs while avoiding unsustainable debt burdens for the nations of the region."

US Vice President Mike Pence was even more blunt during his speech at the APEC summit.

US Vice President Mike Pence was even more blunt during his speech at the APEC summit.

Taking a swipe at China, he said that the US "offers a better option" and "does not drown partners in a sea of debt... coerce" them or "compromise" their independence.

To indicate that the US and allied powers were serious about using economic and military means to counter Chinese influence, Pence announced over the weekend the US will join with Australia and PNG to redevelop and create a joint naval base on Manus Island.

To indicate that the US and allied powers were serious about using economic and military means to counter Chinese influence, Pence announced over the weekend the US will join with Australia and PNG to redevelop and create a joint naval base on Manus Island.

"We will work with these two nations to protect sovereignty and maritime rights in the Pacific Islands," he said.

Public distaste for 'sharp power' on show

Previously, in August, it was reported that China could be given the contract to redevelop a port on Manus Island.

Public distaste for 'sharp power' on show

Previously, in August, it was reported that China could be given the contract to redevelop a port on Manus Island.

A military facility on Manus Island is of high strategic significance -- this is a deep-water port capable of hosting aircraft carriers and hundreds of naval vessels.

As one of the most important bases for the US fleet in the Pacific theater during World War II, it will be a second line of defence should China's People's Liberation Army Navy successfully break out of the so-called First Island Chain, a line of archipelagos that cover the Kuril Islands, Japan, Taiwan, northern Philippines and Borneo, and the Malay Peninsula.

But even if the reports about Chinese involvement in the Manus Island port are untrue, Beijing would be alarmed at the prospect of American and Australian military assets in PNG to counter any Chinese naval breakout.

As one of the most important bases for the US fleet in the Pacific theater during World War II, it will be a second line of defence should China's People's Liberation Army Navy successfully break out of the so-called First Island Chain, a line of archipelagos that cover the Kuril Islands, Japan, Taiwan, northern Philippines and Borneo, and the Malay Peninsula.

But even if the reports about Chinese involvement in the Manus Island port are untrue, Beijing would be alarmed at the prospect of American and Australian military assets in PNG to counter any Chinese naval breakout.

As far as Beijing is concerned, the weekend was the time to showcase China's emergence as a benign superpower in the South Pacific.

Instead, public distaste for and rebuke of its 'sharp power' was on show.

Xi defended China's trade practices and denied that its Belt and Road Initiative contained hidden geo-political and other sinister motivations.

Xi defended China's trade practices and denied that its Belt and Road Initiative contained hidden geo-political and other sinister motivations.

And no matter how adamantly he did so, it was not a conversation that Xi intended to have when he first landed in Port Moresby.

And it has not ended.

The more China offers economic largesse and inducements, the more it will need to reassure the recipient and the world that it is not laying a 'debt trap' or seeking to buy influence.

The weekend was supposed to be China's moment in the sun during this most important regional economic meeting.

And it has not ended.

The more China offers economic largesse and inducements, the more it will need to reassure the recipient and the world that it is not laying a 'debt trap' or seeking to buy influence.

The weekend was supposed to be China's moment in the sun during this most important regional economic meeting.

Instead, it became obvious to all that Beijing's ambitions are as feared and resisted by at least as many countries, as welcomed by others.

jeudi 4 janvier 2018

Chinese Peril

A look at China's pervasive attempts to exert its influence around the world

By Jessica Meyers

Beijing stooge Sam Dastyari

A foreign government accused of infiltrating schools, the legislature and the media, using its agents to monitor students and influence politicians.

It looked like a campaign of espionage and interference that a top intelligence official warned could “cause serious harm to the nation’s sovereignty, the integrity of our political system, our national security capabilities, our economy and other interests.”

Forget, for a moment anyway, Russia meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential race.

Beijing stooge Sam Dastyari

A foreign government accused of infiltrating schools, the legislature and the media, using its agents to monitor students and influence politicians.

It looked like a campaign of espionage and interference that a top intelligence official warned could “cause serious harm to the nation’s sovereignty, the integrity of our political system, our national security capabilities, our economy and other interests.”

Forget, for a moment anyway, Russia meddling in the 2016 U.S. presidential race.

This was China meddling in Australia.

The reports last year suggested that the Communist Party was taking extreme measures to extend influence beyond its borders.

The reports last year suggested that the Communist Party was taking extreme measures to extend influence beyond its borders.

The strains between the two countries illustrate a tension many Western powers now face: how to engage with an increasingly powerful, one-party state without sacrificing their democratic interests.

The conflict threatens to blow up relations between China and Australia.

Here’s a primer on the situation:

What happened?

In June, Fairfax Media and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, two of the country’s most influential news organizations, published a five-month investigation detailing China’s campaign.

The stories described threats against parents in China for their sons’ involvement in democracy protests in Australia, the detention of a Chinese-born academic during a visit there, donations from pro-Beijing businesses to the campaigns of Australian senators, and the party’s grip over Chinese-language media on the island.

The country’s domestic spy chief, Duncan Lewis, told lawmakers in June that espionage and Chinese interference were occurring at “an unprecedented scale” and were a threat to the country’s institutions, politics and economy.

In the fallout, anti-China sentiments have blossomed.

The conflict threatens to blow up relations between China and Australia.

Here’s a primer on the situation:

What happened?

In June, Fairfax Media and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, two of the country’s most influential news organizations, published a five-month investigation detailing China’s campaign.

The stories described threats against parents in China for their sons’ involvement in democracy protests in Australia, the detention of a Chinese-born academic during a visit there, donations from pro-Beijing businesses to the campaigns of Australian senators, and the party’s grip over Chinese-language media on the island.

The country’s domestic spy chief, Duncan Lewis, told lawmakers in June that espionage and Chinese interference were occurring at “an unprecedented scale” and were a threat to the country’s institutions, politics and economy.

In the fallout, anti-China sentiments have blossomed.

In December, Australian Sen. Sam Dastyari resigned after reports that he’d warned a political donor with Communist Party ties that his phone was likely tapped by government agencies.

Dastyari also lauded China’s efforts to build islands in the South China Sea, countering his party’s position.

Are China’s influence operations different from those of other countries?

Countries regularly try to project positive images of themselves abroad, from international broadcasts to funding for educational institutions.

Are China’s influence operations different from those of other countries?

Countries regularly try to project positive images of themselves abroad, from international broadcasts to funding for educational institutions.

But under Xi Jinping, an emboldened China appears to be setting new standards.

Beijing has spent more than $6 billion to modernize and expand its sprawling propaganda apparatus, which includes a global television channel and state-run news bureaus throughout the world.

Perhaps more importantly, the party agency known as the United Front Work Department embeds partners into community associations, universities and other institutions to promote China’s interests, according to John Fitzgerald, a professor at the Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne who studies Chinese civil society.

“The most important feature of China’s propaganda operations is not content production or information dissemination but efforts at content control and suppression,” he said.

“China’s party leadership is quite explicit that one of its enemies is liberal democracy, another, the universal values that underpin democracy,” he said.

Beijing has spent more than $6 billion to modernize and expand its sprawling propaganda apparatus, which includes a global television channel and state-run news bureaus throughout the world.

Perhaps more importantly, the party agency known as the United Front Work Department embeds partners into community associations, universities and other institutions to promote China’s interests, according to John Fitzgerald, a professor at the Swinburne University of Technology in Melbourne who studies Chinese civil society.

“The most important feature of China’s propaganda operations is not content production or information dissemination but efforts at content control and suppression,” he said.

“China’s party leadership is quite explicit that one of its enemies is liberal democracy, another, the universal values that underpin democracy,” he said.

“It will strike down enemies when and where it can.”

Researchers at the National Endowment for Democracy — a Washington nonprofit funded partly by Congress to promote democracy abroad — label China’s methods “sharp power.”

Researchers at the National Endowment for Democracy — a Washington nonprofit funded partly by Congress to promote democracy abroad — label China’s methods “sharp power.”

Such behavior seeks to influence through manipulation or distortion rather than soft power attempts to win “hearts and minds.”

How did China respond to the accusations?

State media called the allegations an attack on Chinese people, a standard response that immediately transforms the issue into a racial one.

How did China respond to the accusations?

State media called the allegations an attack on Chinese people, a standard response that immediately transforms the issue into a racial one.

Nearly 60% of Chinese polled by the Global Times, a Communist Party tabloid, now consider Australia the least-friendly country to China.

How does this affect international relations?

Australia relies on China as its largest trading partner. China is the destination for more than a third of Australia’s exports, and its hunger for iron ore and coal helped spare Australia from the withering effects of the 2008 global financial crisis.

The scandal comes amid uncertainty over what role the United States — Australia’s most important military ally — will play in the region with a Trump administration heavy on protectionist rhetoric.

“This is the first time in our history that our dominant trading partner is not also a dominant security partner,” Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said in November.

That concern rang out clearly when he recently announced vast foreign interference legislation that the Parliament is expected to vote on later this year.

How does this affect international relations?

Australia relies on China as its largest trading partner. China is the destination for more than a third of Australia’s exports, and its hunger for iron ore and coal helped spare Australia from the withering effects of the 2008 global financial crisis.

The scandal comes amid uncertainty over what role the United States — Australia’s most important military ally — will play in the region with a Trump administration heavy on protectionist rhetoric.

“This is the first time in our history that our dominant trading partner is not also a dominant security partner,” Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull said in November.

That concern rang out clearly when he recently announced vast foreign interference legislation that the Parliament is expected to vote on later this year.

The new laws would ban foreign political donations in Australia.

In his announcement, Turnbull mentioned no specific country, but he alternated between Mandarin and English and played off a phrase used by Mao Tse-tung when he founded modern China.

“The Australian people,” he said, “have stood up.”

Concerns about Chinese influence also cross into New Zealand.

In his announcement, Turnbull mentioned no specific country, but he alternated between Mandarin and English and played off a phrase used by Mao Tse-tung when he founded modern China.

“The Australian people,” he said, “have stood up.”

Concerns about Chinese influence also cross into New Zealand.

A University of Canterbury professor recently detailed how the party seeks to install pro-Beijing associates in community associations and steer political donations.

The Financial Times and New Zealand’s Newsroom revealed that Jian Yang, a top Parliament member, failed to disclose his Chinese military intelligence background when he immigrated to New Zealand.

The Financial Times and New Zealand’s Newsroom revealed that Jian Yang, a top Parliament member, failed to disclose his Chinese military intelligence background when he immigrated to New Zealand.

mardi 2 janvier 2018

2017 Was A Bad Year For China. Will 2018 Be Worse?

By Douglas Bulloch

Xi Jinping

It seems like a long time since China was routinely the source of good news.

Xi Jinping

It seems like a long time since China was routinely the source of good news.

Growth rates remain impressive, but it is increasingly obvious that they are being bought at the cost of ever rising debt.

Aside from that, there are routine announcements that indicate senior figures are trying to address a range of problems, and bold proclamations about China's ascendant place in the region, but these announcements now seem to raise many questions as once they merely raised expectations.

Warnings from the I.M.F. have started to resemble those from the B.I.S., while Moody's and S&P's have matched each other's pessimism over China's ability to get ahead of its ballooning debt without a dramatic correction.

Warnings from the I.M.F. have started to resemble those from the B.I.S., while Moody's and S&P's have matched each other's pessimism over China's ability to get ahead of its ballooning debt without a dramatic correction.

Optimists remain, of course, but explanations of exactly how China resolves its contradictory tensions between economic growth and rising debt are becoming less plausible as time passes.

Since the beginning of the year, and Xi Jinping's dramatic bid for world leadership amid the fawning plutocrats at Davos, there has been little progress on the economic front.

Since the beginning of the year, and Xi Jinping's dramatic bid for world leadership amid the fawning plutocrats at Davos, there has been little progress on the economic front.

One might even argue there have been many reverses.

The capital account remains essentially closed (and getting tighter), the currency is now less traded than it was in 2016 and the stock market is plagued by efforts to second guess the intentions of the "national team" conducting state backed intervention to stabilise market valuations.

State capitalism may still have its advocates, but the jury is well and truly out.

Sharp Power?

On the geopolitical front, the establishment of military installations on artificial islands in the South China Sea has continued largely unopposed, but there is no doubt tensions are rising.

Sharp Power?

On the geopolitical front, the establishment of military installations on artificial islands in the South China Sea has continued largely unopposed, but there is no doubt tensions are rising.

Moreover, China has for years insisted its intentions are peaceful, while giving weaker neighbours less and less reasons to believe them.

This year end, no one can any longer doubt what is taking place.

Then when it comes to the Belt and Road Initiative, Xi's signature foreign policy, the news is also turning sour.

Then when it comes to the Belt and Road Initiative, Xi's signature foreign policy, the news is also turning sour.

On the one hand the collapse of the Venezuelan economy, after an estimated $60 billion lifeline from China raises the possibility of severe losses – SOE Sinopec recently commenced legal action against PDVSA for payment of some ultimately trifling sum – on the sort of risky foreign loans that have attracted praise in the past.

In Sri Lanka, China has taken on a 99 year lease on a Chinese financed port on account of Sri Lanka not being able to make the payments.

In Sri Lanka, China has taken on a 99 year lease on a Chinese financed port on account of Sri Lanka not being able to make the payments.

Perhaps this is justifiable, but is anyone in China thinking about what this looks like?

Because even if not, people in the region certainly are.

Very much in view of the difficulties Sri Lanka was finding itself in, Pakistan and Nepal cancelled China financed projects precisely because they are beginning to wonder about the strings of influence that come ready attached.

Nevertheless China's particular brand of economic and political conditionality has now acquired its own vocabulary with the term "Sharp Power," describing the kind of coherent, full-spectrum interest peddling that should be familiar to most China watchers by now.

Nevertheless China's particular brand of economic and political conditionality has now acquired its own vocabulary with the term "Sharp Power," describing the kind of coherent, full-spectrum interest peddling that should be familiar to most China watchers by now.

This way of qualifying power dates back to Joseph Nye's conception of "Hard" and "Soft" power, from which he himself later extracted the term "Smart Power" in an attempt to remind hubristic neo-cons of the George W. Bush administration that "Soft" power mattered too.

"Sharp" power seems, by contrast, to be an attempt to qualify China's reputation for prioritizing the "Soft" power of economic development and friendly cooperation by reminding people that China is willing to play hardball when it matters.

Ultimately, this shouldn't surprise anyone, but it should worry China that this is increasingly their reputation.

If people around the world are seeking less dependence on the U.S. it is unlikely they want to become more dependent on China.

New Year Forebodings?

The really extraordinary thing about 2017 is how abruptly the China story has reversed.

New Year Forebodings?

The really extraordinary thing about 2017 is how abruptly the China story has reversed.

From one of assured economic management leading inevitably to a position of strategic influence, we have instead witnessed a story of expanding economic risks and uncertainty, unaddressed problems of administrative and economic reforms, crackdown after crackdown from the economy to the political and social sphere – extending to an attempt to prevent Christmas celebrations as a foreign contaminant – all the way to migrant workers being hosed and bulldozed off the streets of Beijing.

Then there is the strategic setback of the U.S. breathing life back into the "Quad" and laying the foundations for a reassertion of U.S. backed multi-polar alliances throughout the "Indo-Pacific."

Then there is the strategic setback of the U.S. breathing life back into the "Quad" and laying the foundations for a reassertion of U.S. backed multi-polar alliances throughout the "Indo-Pacific."

This steady push-back against Chinese influence comes because China routinely seeks confrontation, most recently with India over Doklam, but also against South Korea for the temerity they displayed in permitting the U.S. to base THAAD missiles in their country.

Indeed, while China and South Korea appeared to be on better terms, when the South Korean President paid a visit, China has subsequently doubled down with the economic boycotts.

Perhaps the smiles and handshakes covered over the possibility that China did not get their way?

With the U.S. primed for a resumption of trade action in the New Year, North Korea boiling hot again and Japan considering the purchase of the F35-B for their flat-top "destroyers" there is an unmistakable atmosphere of pressure growing across the region.

With the U.S. primed for a resumption of trade action in the New Year, North Korea boiling hot again and Japan considering the purchase of the F35-B for their flat-top "destroyers" there is an unmistakable atmosphere of pressure growing across the region.

It is still possible to read boosterish comment pieces about China driving the world economy ever upwards, but more common comes the concern.

vendredi 15 décembre 2017

Sunlight v subversion: What to do about China’s infiltration?

China is manipulating decision-makers in Western democracies. The best defence is transparency.

What to do?

Facing complaints from Australia and Germany, China has called its critics irresponsible and paranoid.

The Economist

WHEN a rising power challenges an incumbent one, war often follows.

WHEN a rising power challenges an incumbent one, war often follows.

That prospect, known as the Thucydides trap after the Greek historian who first described it, looms over relations between China and the West, particularly America.

So, increasingly, does a more insidious confrontation.

Even if China does not seek to conquer foreign lands, it seeks to conquer foreign minds.

Australia was the first to raise a red flag about China’s tactics.

Australia was the first to raise a red flag about China’s tactics.

On December 5th allegations that China has been interfering in Australian politics, universities and publishing led the government to propose new laws to tackle “unprecedented and increasingly sophisticated” foreign efforts to influence lawmakers (see article).

This week an Australian senator resigned over accusations that, as an opposition spokesman, he took money from China and argued its corner.

Britain, Canada and New Zealand are also beginning to raise the alarm.

On December 10th Germany accused China of trying to groom politicians and bureaucrats.

And on December 13th Congress held hearings on China’s growing influence.

This behaviour has a name—“sharp power”, coined by the National Endowment for Democracy, a Washington-based think-tank.

This behaviour has a name—“sharp power”, coined by the National Endowment for Democracy, a Washington-based think-tank.

“Soft power” harnesses the allure of culture and values to add to a country’s strength; sharp power helps authoritarian regimes coerce and manipulate opinion abroad.

The West needs to respond to China’s behaviour, but it cannot simply throw up the barricades.

The West needs to respond to China’s behaviour, but it cannot simply throw up the barricades.

Unlike the old Soviet Union, China is part of the world economy.

Instead, in an era when statesmanship is in short supply, the West needs to find a statesmanlike middle ground.

That starts with an understanding of sharp power and how it works.

Influencing the influencers

China has long tried to use visas, grants, investments and culture to pursue its interests.

Influencing the influencers

China has long tried to use visas, grants, investments and culture to pursue its interests.

But its actions have recently grown more intimidating and encompassing.

Its sharp power has a series of interlocking components: subversion, bullying and pressure, which combine to promote self-censorship.

For China, the ultimate prize is pre-emptive kowtowing by those whom it has not approached, but who nonetheless fear losing funding, access or influence.

China has a history of spying on its diaspora, but the subversion has spread.

China has a history of spying on its diaspora, but the subversion has spread.

In Australia and New Zealand Chinese money has bought influence in politics, with party donations or payments to individual politicians.

This week’s complaint from German intelligence said that China was using the LinkedIn business network to ensnare politicians and government officials, by having people posing as recruiters and think-tankers and offering free trips.

Bullying has also taken on a new menace.

Bullying has also taken on a new menace.

Sometimes the message is blatant, as when China punished Norway economically for awarding a Nobel peace prize to a Chinese pro-democracy activist.

More often, as when critics of China are not included in speaker line-ups at conferences, or academics avoid study of topics that China deems sensitive, individual cases seem small and the role of officials is hard to prove.

But the effect can be grave.

Western professors have been pressed to recant.

Foreign researchers may lose access to Chinese archives.

Policymakers may find that China experts in their own countries are too ill-informed to help them.

Because China is so integrated into economic, political and cultural life, the West is vulnerable to such pressure.

Because China is so integrated into economic, political and cultural life, the West is vulnerable to such pressure.

Western governments may value trade over scoring diplomatic points, as when Greece vetoed a European Union statement criticising China’s record on human rights, shortly after a Chinese firm had invested in the port of Piraeus.

The economy is so big that businesses dance to China’s tune without being told to.

An Australian publisher suddenly pulled a book, citing fears of “Beijing’s agents of influence”.

China's new weapon to infiltrate the West: LinkedIn

What to do?

Facing complaints from Australia and Germany, China has called its critics irresponsible and paranoid.

However, if China were being more truthful, it would point out that its desire for influence is what happens when countries become powerful.

China has a lot more at stake outside its borders today than it did.

China has a lot more at stake outside its borders today than it did.

Some 10m Chinese have moved abroad since 1978.

It worries that they will pick up democratic habits from foreigners and infect China itself.

Separately, Chinese companies are investing in rich countries, including in resources, strategic infrastructure and farmland.

China’s navy can project power far from home.

Its government frets that its poor image abroad will do it harm.

And as the rising superpower, China has an appetite to shape the rules of global engagement—rules created largely by America and western Europe and routinely invoked by them to justify their own actions.

Open societies ignore China’s sharp power at their peril.

Part of their defence should be practical.

Part of their defence should be practical.

Counter-intelligence, the law and an independent media are the best protection against subversion.

All three need Chinese speakers who grasp the connection between politics and commerce in China. The Chinese Communist Party suppresses free expression, open debate and independent thought to cement its control.

Merely shedding light on its sharp tactics—and shaming kowtowers—would go a long way towards blunting them.

Ignoring manipulation in the hope that China will be more friendly in the future would only invite the next jab.

Instead the West needs to stand by its own principles, with countries acting together if possible, and separately if they must.

The first step in avoiding the Thucydides trap is for the West to use its own values to blunt China’s sharp power.

Inscription à :

Articles (Atom)