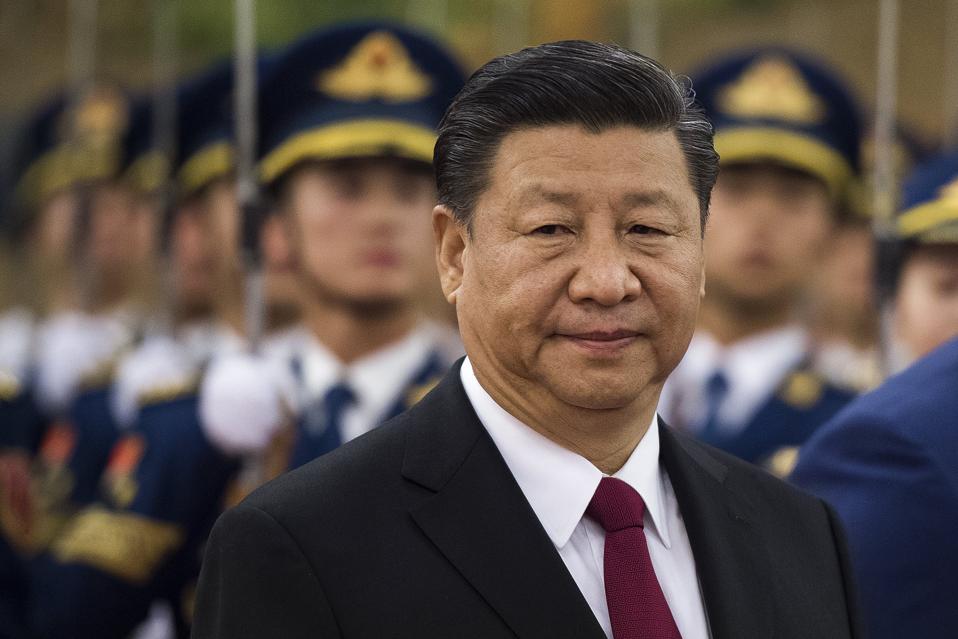

Xi Jinping

It seems like a long time since China was routinely the source of good news.

Growth rates remain impressive, but it is increasingly obvious that they are being bought at the cost of ever rising debt.

Aside from that, there are routine announcements that indicate senior figures are trying to address a range of problems, and bold proclamations about China's ascendant place in the region, but these announcements now seem to raise many questions as once they merely raised expectations.

Warnings from the I.M.F. have started to resemble those from the B.I.S., while Moody's and S&P's have matched each other's pessimism over China's ability to get ahead of its ballooning debt without a dramatic correction.

Warnings from the I.M.F. have started to resemble those from the B.I.S., while Moody's and S&P's have matched each other's pessimism over China's ability to get ahead of its ballooning debt without a dramatic correction.

Optimists remain, of course, but explanations of exactly how China resolves its contradictory tensions between economic growth and rising debt are becoming less plausible as time passes.

Since the beginning of the year, and Xi Jinping's dramatic bid for world leadership amid the fawning plutocrats at Davos, there has been little progress on the economic front.

Since the beginning of the year, and Xi Jinping's dramatic bid for world leadership amid the fawning plutocrats at Davos, there has been little progress on the economic front.

One might even argue there have been many reverses.

The capital account remains essentially closed (and getting tighter), the currency is now less traded than it was in 2016 and the stock market is plagued by efforts to second guess the intentions of the "national team" conducting state backed intervention to stabilise market valuations.

State capitalism may still have its advocates, but the jury is well and truly out.

Sharp Power?

On the geopolitical front, the establishment of military installations on artificial islands in the South China Sea has continued largely unopposed, but there is no doubt tensions are rising.

Sharp Power?

On the geopolitical front, the establishment of military installations on artificial islands in the South China Sea has continued largely unopposed, but there is no doubt tensions are rising.

Moreover, China has for years insisted its intentions are peaceful, while giving weaker neighbours less and less reasons to believe them.

This year end, no one can any longer doubt what is taking place.

Then when it comes to the Belt and Road Initiative, Xi's signature foreign policy, the news is also turning sour.

Then when it comes to the Belt and Road Initiative, Xi's signature foreign policy, the news is also turning sour.

On the one hand the collapse of the Venezuelan economy, after an estimated $60 billion lifeline from China raises the possibility of severe losses – SOE Sinopec recently commenced legal action against PDVSA for payment of some ultimately trifling sum – on the sort of risky foreign loans that have attracted praise in the past.

In Sri Lanka, China has taken on a 99 year lease on a Chinese financed port on account of Sri Lanka not being able to make the payments.

In Sri Lanka, China has taken on a 99 year lease on a Chinese financed port on account of Sri Lanka not being able to make the payments.

Perhaps this is justifiable, but is anyone in China thinking about what this looks like?

Because even if not, people in the region certainly are.

Very much in view of the difficulties Sri Lanka was finding itself in, Pakistan and Nepal cancelled China financed projects precisely because they are beginning to wonder about the strings of influence that come ready attached.

Nevertheless China's particular brand of economic and political conditionality has now acquired its own vocabulary with the term "Sharp Power," describing the kind of coherent, full-spectrum interest peddling that should be familiar to most China watchers by now.

Nevertheless China's particular brand of economic and political conditionality has now acquired its own vocabulary with the term "Sharp Power," describing the kind of coherent, full-spectrum interest peddling that should be familiar to most China watchers by now.

This way of qualifying power dates back to Joseph Nye's conception of "Hard" and "Soft" power, from which he himself later extracted the term "Smart Power" in an attempt to remind hubristic neo-cons of the George W. Bush administration that "Soft" power mattered too.

"Sharp" power seems, by contrast, to be an attempt to qualify China's reputation for prioritizing the "Soft" power of economic development and friendly cooperation by reminding people that China is willing to play hardball when it matters.

Ultimately, this shouldn't surprise anyone, but it should worry China that this is increasingly their reputation.

If people around the world are seeking less dependence on the U.S. it is unlikely they want to become more dependent on China.

New Year Forebodings?

The really extraordinary thing about 2017 is how abruptly the China story has reversed.

New Year Forebodings?

The really extraordinary thing about 2017 is how abruptly the China story has reversed.

From one of assured economic management leading inevitably to a position of strategic influence, we have instead witnessed a story of expanding economic risks and uncertainty, unaddressed problems of administrative and economic reforms, crackdown after crackdown from the economy to the political and social sphere – extending to an attempt to prevent Christmas celebrations as a foreign contaminant – all the way to migrant workers being hosed and bulldozed off the streets of Beijing.

Then there is the strategic setback of the U.S. breathing life back into the "Quad" and laying the foundations for a reassertion of U.S. backed multi-polar alliances throughout the "Indo-Pacific."

Then there is the strategic setback of the U.S. breathing life back into the "Quad" and laying the foundations for a reassertion of U.S. backed multi-polar alliances throughout the "Indo-Pacific."

This steady push-back against Chinese influence comes because China routinely seeks confrontation, most recently with India over Doklam, but also against South Korea for the temerity they displayed in permitting the U.S. to base THAAD missiles in their country.

Indeed, while China and South Korea appeared to be on better terms, when the South Korean President paid a visit, China has subsequently doubled down with the economic boycotts.

Perhaps the smiles and handshakes covered over the possibility that China did not get their way?

With the U.S. primed for a resumption of trade action in the New Year, North Korea boiling hot again and Japan considering the purchase of the F35-B for their flat-top "destroyers" there is an unmistakable atmosphere of pressure growing across the region.

With the U.S. primed for a resumption of trade action in the New Year, North Korea boiling hot again and Japan considering the purchase of the F35-B for their flat-top "destroyers" there is an unmistakable atmosphere of pressure growing across the region.

It is still possible to read boosterish comment pieces about China driving the world economy ever upwards, but more common comes the concern.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire