It is High Time to Outmaneuver Beijing in the South China SeaBy Ross Babbage

The policy of the United States in the South China Sea has failed.

The policy of the United States in the South China Sea has failed.

Repeated statements of limited interest accompanied by occasional ship and aircraft passages have failed to prevent Beijing’s program of island creation, nor have they meaningfully forestalled China’s quest for

military dominance in the region.

In seeking to minimize the risk of confrontation at every step, the United States have effectively ceded control of a highly strategic region and presided over a process of incremental capitulation.

Bad precedents have been set, and poor messages have been transmitted to the global community.

In parts of the Western Pacific, the allies are in danger of losing their long-held status as the security partners of choice.

Why has Washington been so flat-footed?

Why has it taken so long to develop an effective counter-strategy to

Beijing’s island creation and militarization in the South China Sea?

Part of the reason is the way that China has asserted its sovereignty over some

80 percent of this strategic waterway.

The South China Sea is a stretch of water that carries more than

half of the world’s merchant tonnage and serves as an important transit route for the militaries of the United States and many of its allies and friends.

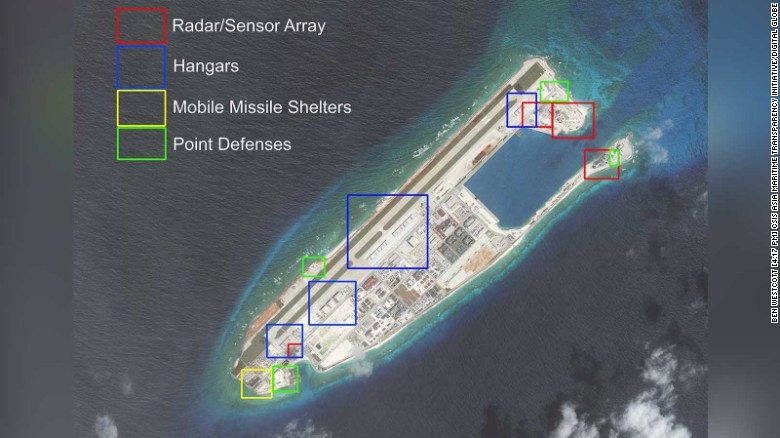

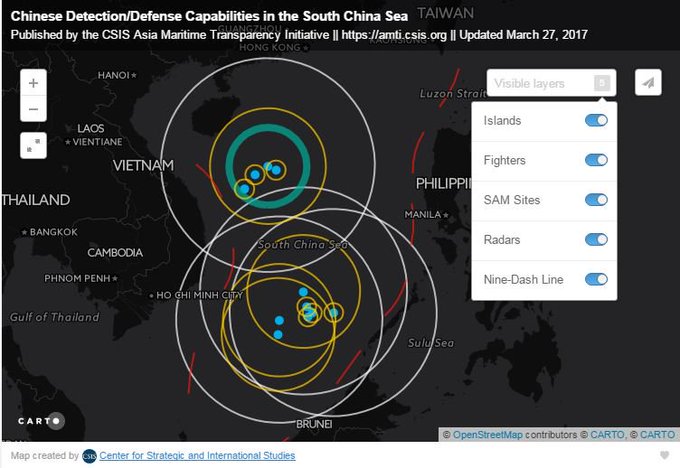

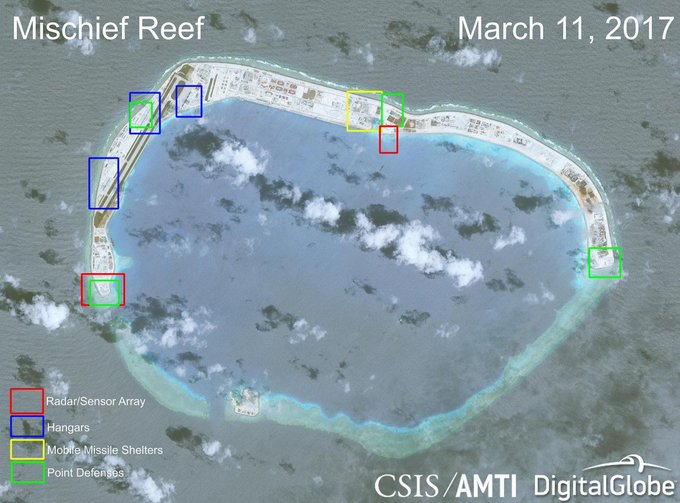

During the last five years, Beijing’s footprint has expanded markedly with the dredging-up of new islands and the construction of facilities for surveillance, anti-air, anti-shipping, and strike forces. Beijing’s campaign has been cleverly conducted via a succession of modest incremental steps, each of which has fallen below the threshold that would trigger a forceful Western response.

Three of the islands in the Spratly group, towards of the middle of the South China Sea, now possess

10,000 foot airfields that are more than adequate to handle Boeing 747 operations.

Hardened revetments to house

24 fighter-bomber aircraft are nearing completion on these three islands together with what appears to be extensive maintenance and storage facilities for fuel and other supplies.

Aircraft operating from these facilities could range as far as the Andaman Sea, Northern Australia, and Guam.

These newly created islands also appear to have capacities to house, as well as operate at short notice, significant numbers of short-and medium-range ballistic and cruise missiles with capabilities to strike both land-based targets and ships at sea as far away as the Sulu Sea in the Philippines and Singapore and Malaysia to the south.Port facilities have also been built on these islands capable of refuelling and replenishing significant numbers of naval, coastguard, and maritime militia vessels.

In addition, these islands appear to have the potential to support an underwater acoustic surveillance network across the South China Sea that would significantly enhance China’s capabilities to prosecute operations against allied submarines in the theater.Because these three primary islands are not very small, there is space to disperse most deployed People’s Liberation Army (PLA) assets in a crisis and complicate targeting by allied forces.

In consequence, China appears well on the way to converting the South China Sea into something approaching a heavily defended internal waterway.

At present, innocent passage, especially by commercial vessels, is being respected.

Military facilities now nearing completion will permit Chinese forces to enforce any such declaration with fighter intercepts of non-complying aircraft.

Although most international observers had few doubts that many of China’s actions in the South China Sea were serious breaches of international law,

the ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration for UNCLOS in July 2016 made the extent of Beijing’s transgressions clear.

It concluded unanimously that there was no legal basis for China’s claim of historic rights to the sea areas and artificial islands falling within the nine-dash line claimed by Beijing.When confronted by China’s territorial and military expansion in the South China Sea, American leaders have almost always responded by repeating a

standard mantra: We have a strong interest in free sea and air passage, we have no national claims to territories in the area, and we call on all parties to exercise restraint and resolve competing claims in accordance with international law.

In token support of these interests, allied ships and aircraft have periodically transited the region, though they have rarely challenged China’s territorial claims directly.

This response has clearly failed to deter Beijing’s territorial expansion.

Why has the approach of the United States been so timid and ineffectual?

There have been several factors at play.

First, many in Washington and in other allied capitals have viewed the problems in the South China Sea as unwelcome distractions of little consequence that are best ignored.

Some policymakers and commentators have argued that there is little sense in risking a major power confrontation over a

“few scattered rocks” in a far distant theater.

Second, the level of importance accorded to the strategic future of the South China Sea varies greatly between allied and partner capitals.

The general view in Washington is that the South China Sea is important but not vital.

It is simply one of many troubled areas with which the United States must deal.

In Tokyo, Seoul, and Canberra, the South China Sea is far more important because of its intrinsic strategic value and critical importance to their close partners who are maritime members of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN).

For the littoral states of the South China Sea, the strategic balance and effective sovereignty of the region is critical for their future security and economic well-being.

These differences in priority between the Western Pacific allies and their friends are placing strains on long-standing security relationships.

A third serious constraint has been imposed by the hub-and-spokes alliance model that has been in place in the Western Pacific since the 1950s.

Cross-alliance (outer wheel) cooperation and combined security planning is not well-developed amongst the Western Pacific allies.

While some progress has been made in recent years in strengthening operational coordination between Japan, Australia, South Korea and some partner countries in Southeast Asia, it is still limited and much of it is not routine.

Washington has certainly encouraged closer cross-alliance cooperation but and it has a long way to go to approach the type of combined security planning that is habitual in Europe.

In consequence, timely, efficient, and effective alliance cooperation in response to Beijing’s operations in the South China Sea has not been straightforward.

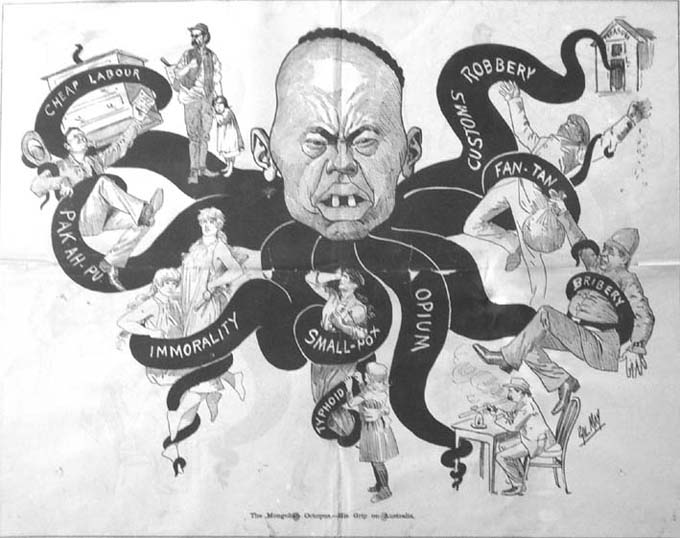

Fourth, most citizens, almost all journalists, and many congressional and parliamentary representatives are poorly informed about Chinese operations in the South China Sea and, indeed, Beijing’s broader strategic behavior during the last decade.

The mainstream media and Western government agencies have done a poor job of displaying the reality of what has been happening and explaining the implications.

Fifth, the development of an effective response to China’s creeping incrementalism in the South China Sea has been intrinsically difficult.

Beijing has employed a very sophisticated strategy and operational concept that could be implemented without challenging U.S. alliance commitments or directly confronting American or allied forces.

Moreover, Western leaders have faced numerous political and bureaucratic distractions, and it has been hard to maintain their attention on this theater.

Sixth, many Western business people and policymakers have wished to avoid any measure that could disturb their business and broader economic relationships with China.

These concerns have been most apparent in the Western Pacific allies, as well as in American and other corporations that have invested heavily in developing close ties with Chinese enterprises.

Chinese agencies have been active in fostering these worries, propagating false dilemmas, and exaggerating the potential consequences for regional economies of any actions taken to confront China’s assertiveness.

The success of Beijing’s information operations in Western countries is a seventh factor in accounting for the Western allies’ timidity over Chinese behavior in the South China Sea.

Cyber and intelligence operations have been used to reinforce key messages, recruit Chinese intelligence agents and “agents of influence,” and to intimidate, coerce, and deter allied counter-actions.

An eighth contributing factor is cultural.

Western electorates appear to be more fearful of triggering confrontation and the escalation of an argument than their Chinese counterparts.

Hugh White, a well-known observer of the region’s affairs, has even argued that

the United States should not confront China’s expansionism unless its leaders are willing to “convince a majority of Americans that America should and would be willing to fight a nuclear war to preserve U.S. leadership in Asia.”

Statements such as this reflect flawed assessments of relative power, dubious assumptions about Beijing’s preparedness to use nuclear weapons against the United States, and a failure to consider the range of possible allied strategies and the very large menu of non-military options available to the allies to curb China’s adventurism.

One of the core problems with the approach of the U.S., Japanese, and Australian governments has been their serious misstatement of alliance interests.

These allies certainly have strong interests in freedom of air and sea navigation and in seeing the competing claims in the region resolved peacefully in accordance with international law.

However, the most powerful interests of the allies really extend beyond these limited, largely tactical, goals.

- In reality, the first key interest of the allies is ensuring that China does not dominate the South China Sea to the extent that it can unilaterally determine the regional order and dictate the level of sovereignty to be enjoyed by the littoral states.

- A second key interest of the allies is limiting the potential for China’s acquisitive actions in the South China Sea to set a precedent for further, more aggressive illegal actions by Beijing in either the short or the long term.

- A third key allied interest is ensuring that China’s serious breaches of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, its dismissal of the findings of the Tribunal of the Permanent Court of Arbitration, and its direct challenge to international law are not repeated.

In pursuit of these more substantive interests, the allied leaders need to choose a clear strategic concept to drive a counter-campaign.

The most obvious options are to select a strategy of denial, a strategy of cost imposition, a strategy that attacks China’s strategy, or a strategy that undermines the leadership in Beijing.

No matter what strategic concept is selected, an essential foundation should be a stronger and more convincing allied military posture in the Western Pacific.

Given Beijing’s actions during the last five years, there is a need to progress beyond the so-called “pivot” and “rebalancing” to a more thoroughgoing military engagement with the region that might be called the Regional Security Partnership Program.

The primary goals of such a program would be to demonstrate continuing allied military superiority in the theater, deter further Chinese adventurism, and reinforce the confidence of regional allies and partners in the reliability of their Western partners so that they feel able to staunchly resist any attempted Chinese coercion.

The most effective allied strategy will be innovative and asymmetric.

Just because Beijing has focused its most assertive actions in the South China and East China Seas in recent years using various forms of military, coast guard, maritime militia, and political warfare assets, it does not mean that the allies should counter by focusing all of their efforts in those theaters and employing those same modes.

To the contrary, the most effective allied options are likely to focus on applying several types of pressure against the Chinese leadership’s primary weaknesses in whatever theater that is appropriate.

Such campaigns should contain a carefully calibrated mix of measures that can be sustained over an extended period.

Candidate measures will likely extend well beyond the standard diplomatic and military domains to include geo-strategic, information, economic, financial, immigration, legal, counter-leadership, and other initiatives.

Some of these measures would comprise declaratory policies designed to deter Chinese actions, give confidence to allies and friends, and shape the broader operating environment.

Other measures would be classified and designed in part to keep the Chinese off-balance and encourage greater caution in Beijing.

There will certainly be people in allied countries who would prefer their governments to turn a blind eye.

However, the nature and scale of the Chinese challenge means that a failure of the United States to respond with a robust counter-strategy would have fundamental implications for global security.

For a start, it would effectively cede sovereignty over almost all of the South China Sea to China.

Giving Beijing effective control over such a major transport and communications expanse would have very substantial and enduring geo-strategic implications.

It would reconfigure major parts of the security environment in the Western Pacific and seriously complicate many types of future allied operations.

The second major consequence would be acquiescence to Beijing’s serious breaches of international law.

This would do great damage to decades of allied effort to build frameworks of international law that govern international relations, commerce, and international disputes.

It would signal to the global community that the Western allies are not prepared to defend international law.

A third key consequence is the risk of emboldening China to launch other, potentially more serious, acquisitive operations in coming years.

Beijing may view the timidity of other nations as an invitation to seize further strategic territories and undertake other highly assertive operations.

Hence, by remaining timid and flat-footed, allied leaders would run a serious risk of fostering a far more serious conflict with China in coming years that would be much harder and impossible to avoid.

A fourth major consequence of failing to act in a robust manner would be damaging allied deterrence. Weak Western action at this point would send very unfortunate messages not just to Beijing, but also to Moscow and Pyongyang.

A fifth consequence of U.S. inaction would be forcing a major recalibration of defense and broader national security assumptions by almost all allied and friendly states in the Western Pacific, and many beyond.

Given the ineffective responses of allied leaders to such serious transgressions of international law and global security norms, what changes should they make to their own security planning?

Some are already exploring new and potentially more reliable security partnerships.

Others may launch new programs of self-defense, yet others may surrender key elements of their sovereignty to reach accommodations with Beijing or other revisionist regimes.

The security of the Western Pacific remains a core interest of the United States and its close allies. There is a strong imperative for the incoming Trump administration to make the formulation of an effective counter-strategy an early priority.

_disembark_a_Landing_Craft_Utility_(LCU).jpg)