The Case for Congagement with China

The Trump administration should not simply engage or contain China. It needs to blend the two together.By Zalmay Khalilzad

THE TRUMP administration’s China policy is currently focused almost exclusively on North Korea. But Beijing’s growing power and expanding regional and global objectives demand that Washington come to grips with a broader China strategy.

It is imperative to assess China’s current and planned capabilities, its objectives and strategy.

Unlike in its recent history, China is now a rising global power.

Its economy is the second largest in the world, directly behind America’s.

The United States supported China’s rapid industrialization after Richard Nixon’s opening.

Later, it took advantage of the U.S.-backed liberal international order, including the global trading system, to export goods in enormous volume to markets around the world.

China has also committed economic espionage against America, using cyber and other tools to steal intellectual property.

Additionally, China is using regulations to compel U.S. firms to share their core technologies as a condition for gaining access to Chinese customers, even as unfettered access to American markets continues to fuel Chinese growth.

China’s economic growth has brought hundreds of millions of its citizens out of poverty, but not without negative consequences: among them the long-standing one-child requirement, large-scale environmental pollution, and the growing gap between the very rich and everyone else.

China holds more than a trillion dollars in U.S. debt, and has become America’s largest trading partner.

In 2015, U.S. trade with China totaled $659.4 billion—with the American trade deficit standing at $336.2 billion.

Access to the American market has been vital for China’s spectacular growth and remains vital for its future.

China has leveraged its economic power to build up its military capabilities, including space and counter-space; information and electronic warfare; nuclear submarines and other systems needed to sustain a robust second-strike capability; aircraft carriers; amphibious ships; destroyers; transport aircraft and a number of different missile systems.

It has the resources to further expand these capabilities and acquire new ones.

As China’s power has grown, it has developed a huge ambition: to return China to greatness and to replace the United States as the world’s dominant power.

Beijing sees the domination of Asia as a necessary step to achieve its ultimate projection of global predominance.

In the immediate future, China seeks to preclude any U.S. military intervention along its maritime periphery.

Operationally, Beijing’s aim is to exclude others up to the “first island chain,” and seeks to project power all the way to the “second island chain.”

The two-island concept has both defensive and offensive dimensions.

Defensively, China considers the island chains important for avoiding hostile encirclement. Offensively, they could enable an invasion of Taiwan.

Beyond Taiwan and self-defense, China seeks not only to deter and defeat hostile intervention in the area, but also to minimize the U.S. regional role, and to gain dominance over Asia—first Southeast Asia and, over time, Central Asia.

China’s regional strategy has a military and economic prong.

Clearly, China aims to acquire the capability to use decisive force to defeat threats to its interests and resolve territorial disputes quickly, while precluding timely U.S. intervention.

According to Rodrigo Duterte, Xi Jinping threatened war over disputed areas in the South China Sea.

The second prong is economic.

China wants to bring into its orbit a network of countries in Europe, Asia and Africa.

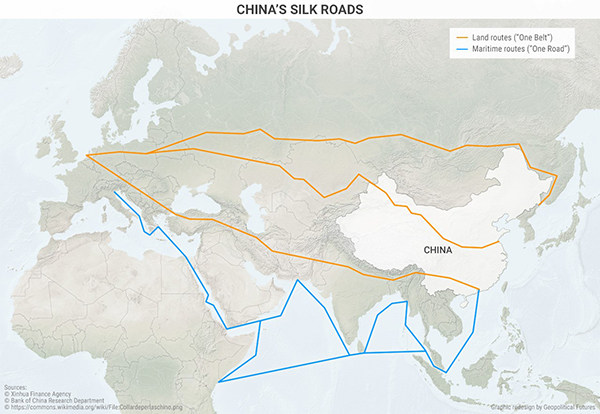

The One Belt, One Road (OBOR) plan and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank are key instruments in the service of this objective.

Greater economic interdependence with regional powers is meant to undermine U.S. alliances by creating incentives to not follow the American lead.

Beijing also warns authoritarian Asian friends that ties to Washington make them vulnerable to U.S. interference in the name of democracy promotion and human rights.

In contrast, China’s policy is not to interfere in their domestic affairs.

While China’s near-to-mid-term focus is on projecting power in Asia, its long-term ambitions go well beyond the region.

China’s ultimate goal is global preeminence.

Beijing is already establishing a permanent naval presence in the Indian Ocean.

It is acquiring facilities in the Persian Gulf and in the Mediterranean, and exploring options for a naval presence in East and West Africa.

As it builds its military power, China wants to avoid the Soviet mistake of placing an unbearable burden on its economy due to excessive military spending.

But as its economy’s size approaches that of the United States’, it likely will also want a comparable military capability and to become a true superpower, with the clout to shape the international order.

CHINA’S TRAJECTORY has important implications for the United States.

As Graham T. Allison argues in his new book,

Destined for War, when rising powers challenge dominant powers, the result is often war.

A strong China likely will behave assertively, especially in its territorial ambitions, its claim on Taiwan and its demand for deference from neighboring countries.

Three factors will be particularly important in how Chinese foreign policy unfolds.

First, Beijing’s perception of the relative balance of power with the United States is critical.

At present, that balance still favors the United States.

China does not want direct conflict with the United States.

It understands the implications of America’s military and technological leadership, the value of Chinese investments in the United States, the vital role of its market for Chinese exports and economic growth, and U.S. global influence.

China remains conscious of its need to “catch up.”

At the same time, Chinese leaders see the United States as a country in decline and unable to sustain its global preeminent role over time.

This encourages Beijing to pursue its objectives patiently. (There have been exceptions to this patience, however. After the financial crisis a decade ago, perhaps believing that U.S. decline had accelerated, it pursued its regional goals more aggressively.)

Second is in internal instability.

A healthy economy has helped China sustain stability, but there are multiple sources of potential instability.

The perpetuation of the gap between economic and political progress could produce increased demands for political freedoms, and the government’s refusal to accommodate these demands could produce a dynamic leading to instability.

There are also regional and ethnic sources of instability.

A serious downturn in the economy could accelerate instability and even lead to conflict and fragmentation—especially if the downturn affected different regions or subsets of the population unequally.

No matter the cause, significant political instability would alter China’s economic viability and its foreign and national-security policies.

Predicting the nature and extent of such an impact is, of course, difficult.

The result could be a China that grows more slowly and is more inward looking, but also a China that is externally more aggressive.

Such aggressiveness could function as a means of distracting an unruly populace from domestic illegitimacy.

Third are regional developments and Chinese responses.

Many Asian countries are alarmed by the surge of Chinese power and Beijing’s push for hegemony under Xi Jinping.

Some convey their concerns openly.

But others, including some U.S. allies, exercise restraint because they do not want to jeopardize economic ties.

Japan, Vietnam and India are among those expressing the most alarm.

Moscow seems more ambivalent, opting to cooperate with China to avoid isolation in the face of its deteriorating relations with the West.

Russia is also concerned, however, that the balance of power is shifting significantly in favor of Beijing.

Indeed, the two countries are competitors in Central Asia.

Regional concerns about China’s aggressive policies can produce responses that ought to constrain Beijing.

Already, neighboring powers are aligning with the United States to balance against China.

It is not outside the realm of possibility that China could miscalculate and become involved in a protracted and costly regional conflict.

A STRATEGY review is one thing.

Developing a long-term strategy that protects and enhances U.S. interests is another entirely.

Like China watchers and strategists outside of government, those within the Trump administration are divided.

Some believe in enhanced engagement—expanding economic and political consultations with China, with the aim of achieving a lasting partnership and mutual accommodation.

Others argue for a blend of prevention and containment.

Engagement could secure Chinese cooperation on current issues of importance, such as North Korea and access to the Chinese markets for American goods and services.

It banks on the belief that continued Chinese economic development, combined with U.S.-China cooperation on issues of mutual interest, has the potential to transform China into a more democratic nation.

Advocates of engagement might argue that, with increased Chinese participation in the international system, Beijing could gradually come to the conclusion that the system and its norms serve its interests.

Some recent statements by Xi, such as in the 2017 meeting of the World Economic Forum and his May 2017 New Silk Road speech in support of globalization, can be interpreted as a "positive" indicator.

Engagement advocates inside the Trump administration might argue that, by the time China becomes strong enough to challenge the international order, it could already have become coopted by it.

But relying on engagement alone is risky.

Expanded U.S. engagement would further help China develop economically and, thus, militarily—enabling it to catch up and even surpass the United States sooner than would otherwise have been the case, and raising the risk of war.

The goal of prevention-plus-containment approach would be to stymie China’s power relative to America’s.

In this view, the United States would not just strengthen its own overall economic and military power, but also seek to contain and weaken China’s.

It would also demonstrate resolve by opposing hostile Chinese policies.

The United States would bolster existing alliances, focus them on counterbalancing China, and forge new alliances and partnerships.

Washington would oppose China’s OBOR policies and start limiting U.S. and allied markets to Chinese exports, so as to slow Beijing’s economic growth.

It might also explore ways to more effectively support those Chinese who seek political reform, greater local autonomy and human rights.

Washington would also redouble efforts to thwart Chinese theft of U.S. technological secrets.

This approach would be a difficult sell domestically.

A policy of prevention plus containment would, moreover, require cooperation from regional allies and from most of the world’s other advanced industrial countries.

For all these reasons, the Trump administration needs a different strategy, one that could accomplish three things: preserve the hope inherent in engagement; preclude Chinese domination of Asia, limiting the relative growth of Chinese power along the way; and hedge against a strong China challenging U.S. interests.

I propose a strategy of “congagement”—a mix of containment and engagement.

The Trump administration should embrace this new tack, tilting toward containment without abandoning engagement.

The goal would be to plausibly convince the Chinese that while the United States is open to cooperation and mutual accommodation, American actions and messaging should aim at convincing the Chinese leaders that a push for hegemony would be resisted by the United States and its allies and partners, including other major regional powers.

Under congagement, the United States would adopt the following twelve tenets:

1) Strengthen America’s overall economic and military power to maintain a favorable global position;

2) Maintain America’s technological lead and discourage friends and allies from contributing to the growth of Chinese military capabilities by strengthening existing export controls that restrict access to Western technology;

3) Pursue a balance-of-power strategy in Asia, by encouraging U.S. allies and partners to build up their military capabilities and to cooperate among themselves to prevent Chinese regional hegemony;

4) Seek to strengthen its own relative capabilities in Asia so it can play the role of balancer and avoid facing a fait accompli when a critical U.S. interest is threatened—for example, by forcing the United States to risk major escalation and high casualties to reinstate the status quo;

5) Dissuade Taiwan from reuniting with the mainland;

6) Use access to American markets and those of regional allies—on which Chinese prosperity depends—as leverage to condition China’s behavior;

7) Rebalance trade to reduce the huge trade deficit;

8) To preserve its technological advantage and preclude new or increased vulnerabilities, review existing agreements with allies and partners, to update and add necessary steps to protect the stealing of technology by the Chinese and avoid the transfer of sensitive technology;

9) At a minimum maintain, but preferably expand, political interaction, military-to-military relations and cultural ties with China;

10) Adjust economic relations by insisting on reciprocity, such as rebalanced trade relations that reduce the huge balance-of-trade deficit;

11) Enhance cooperation on regional issues, including North Korea and terrorism;

12) To increase regional cooperation, crisis prevention and crisis management, encourage an OSCE-type organization in the Asian region with Chinese and U.S. participation. The East Asia Summit might be the best candidate to evolve into such a role, because it has the right membership, but it will need to be properly institutionalized and provided with the right mandate.

This congagement strategy would clarify to Beijing that it is best served by pursuing its interests without undermining the international system.

It would communicate to China the potential costs of turning hostile by demonstrating that the United States is prepared to protect its interests.

It also would highlight that the United States will reciprocate positive Chinese actions.

A congagement strategy would provide the flexibility to adjust the balance between engagement and containment, depending on the state of Chinese capabilities, objectives, policies and actions.

Chinese cooperation on security and economic issues would invite more engagement.

Conversely, inadequate cooperation on, say, North Korea, aggressiveness in the South China Sea and bellicosity on Taiwan would trigger a tilt toward containment.

A combination of containment and engagement promises a superior approach to protecting American interests.

Beijing currently has just one overseas military base, in Djibouti.

Beijing currently has just one overseas military base, in Djibouti.

Michele Geraci, Italy’s under secretary in the economic development ministry. “It is a very fertile area for investment,” he said of the potential influx of money from China.

Michele Geraci, Italy’s under secretary in the economic development ministry. “It is a very fertile area for investment,” he said of the potential influx of money from China. Too much of a good thing?

Too much of a good thing?