By Devlin Barrett and Matt Zapotosky

The Justice Department has charged four members of the Chinese military with a 2017 hack at the credit reporting agency Equifax, a massive data breach that compromised the personal information of nearly half of all Americans.

In a nine-count indictment filed in federal court in Atlanta, federal prosecutors alleged that four members of the People’s Liberation Army hacked into Equifax’s systems, stealing the personal data as well as company trade secrets.

Attorney General William P. Barr called their efforts “a deliberate and sweeping intrusion into the private information of the American people.”

The 2017 breach gave hackers access to the personal information, including Social Security numbers and birth dates, of about 145 million people.

The 2017 breach gave hackers access to the personal information, including Social Security numbers and birth dates, of about 145 million people.

Equifax last year agreed to a $700 million settlement with the Federal Trade Commission to compensate victims.

Those affected can ask for free credit monitoring or, if they already have such a service, a cash payout of up to $125, although the FTC has warned that a large volume of requests could reduce that amount.

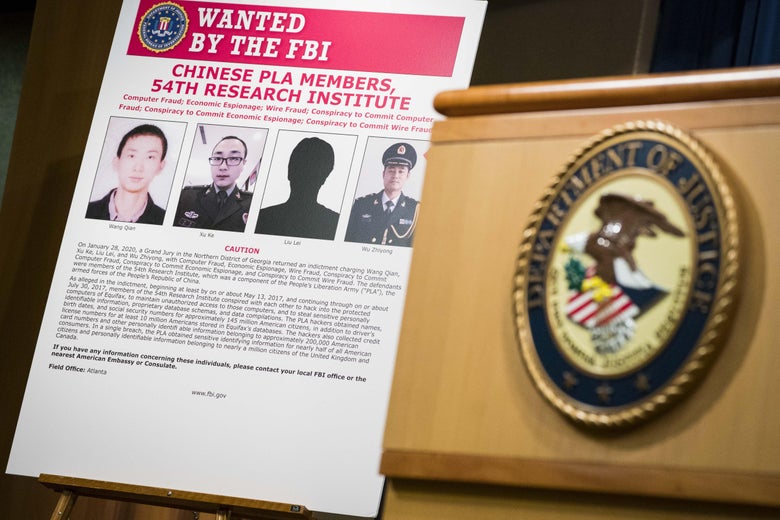

Clockwise from top left: Wang Qian, Xu Ke, Wu Zhiyong and Liu Lei, picture unavailable. The four, all members of the Chinese military, were charged with computer fraud, economic espionage and wire fraud. (FBI)

Clockwise from top left: Wang Qian, Xu Ke, Wu Zhiyong and Liu Lei, picture unavailable. The four, all members of the Chinese military, were charged with computer fraud, economic espionage and wire fraud. (FBI)

At a news conference announcing the indictment, Barr said China has a “voracious appetite” for Americans’ personal information, and he pointed to other intrusions that he alleged have been carried out by Beijing’s actors in recent years, including hacks disclosed in 2015 of the health insurer Anthem and the federal Office of Personnel Management (OPM), as well as a 2018 hack of the hotel chain Marriott.

“This data has economic value, and these thefts can feed China’s development of artificial intelligence tools,” Barr said.

Clockwise from top left: Wang Qian, Xu Ke, Wu Zhiyong and Liu Lei, picture unavailable. The four, all members of the Chinese military, were charged with computer fraud, economic espionage and wire fraud. (FBI)

Clockwise from top left: Wang Qian, Xu Ke, Wu Zhiyong and Liu Lei, picture unavailable. The four, all members of the Chinese military, were charged with computer fraud, economic espionage and wire fraud. (FBI)At a news conference announcing the indictment, Barr said China has a “voracious appetite” for Americans’ personal information, and he pointed to other intrusions that he alleged have been carried out by Beijing’s actors in recent years, including hacks disclosed in 2015 of the health insurer Anthem and the federal Office of Personnel Management (OPM), as well as a 2018 hack of the hotel chain Marriott.

“This data has economic value, and these thefts can feed China’s development of artificial intelligence tools,” Barr said.

The attorney general said the indictment would hold the Chinese military “accountable for their criminal actions.”

William Evanina, director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, characterized the breach as “a counterintelligence attack on the nation,” saying China had long been trying to gather massive amounts of Americans’ personal and sensitive data.

The Washington Post reported in 2015 that the Chinese government has been building huge databases of Americans’ personal information through hacks and making use of data-mining tools to sift through the information for compromising details about key government personnel — making them susceptible to blackmail and, thus, potential spy recruits.

The Washington Post reported in 2015 that the Chinese government has been building huge databases of Americans’ personal information through hacks and making use of data-mining tools to sift through the information for compromising details about key government personnel — making them susceptible to blackmail and, thus, potential spy recruits.

The OPM intrusion, for instance, exposed the private data of more than 21 million government employees, contractors and their families, including a complete history of where they lived and all of their foreign contacts.

U.S. officials said the stolen data could be used to help Chinese intelligence agents target American intelligence officials, but they added that they have seen no evidence yet of such activity.

U.S. officials said the stolen data could be used to help Chinese intelligence agents target American intelligence officials, but they added that they have seen no evidence yet of such activity.

Evanina said his chief concern was that Chinese intelligence agencies could use the stolen data to target those who work at universities or research firms who have access to useful information.

Barr and other U.S. law enforcement officials in recent weeks have taken a particularly aggressive posture toward China.

Barr and other U.S. law enforcement officials in recent weeks have taken a particularly aggressive posture toward China.

Late last week, Barr warned of that country’s bid to dominate the burgeoning 5G wireless market and said the United States and its allies must “act collectively” or risk putting “their economic fate in China’s hands.”

Those charged with the Equifax hack are Wu Zhiyong, Wang Qian, Xu Ke and Liu Lei.

Those charged with the Equifax hack are Wu Zhiyong, Wang Qian, Xu Ke and Liu Lei.

Officials said they were members of the PLA’s 54th Research Institute.

According to the indictment, in March 2017, a software firm announced a vulnerability in one of its products, but Equifax did not patch the vulnerability on its online dispute portal, which used that particular software.

According to the indictment, in March 2017, a software firm announced a vulnerability in one of its products, but Equifax did not patch the vulnerability on its online dispute portal, which used that particular software.

In the months that followed, the Chinese military hackers exploited that unrepaired software flaw to steal vast quantities of Equifax’s files, the indictment charges.

Officials said the hackers also took steps to cover their tracks, routing traffic through 34 servers in 20 countries to hide their location, using encrypted communication channels and wiping logs that might have given away what they were doing.

“American business cannot be complacent about protecting their data,” said FBI Deputy Director David Bowdich.

Barr said that although the Justice Department does not normally charge other countries’ military or intelligence officers outside the United States, there are exceptions, and the indiscriminate theft of civilians’ personal information “cannot be countenanced.”

In the United States, he said, “we collect information only for legitimate, national security purposes.”

None of the four is in custody, and officials acknowledged that there is little prospect they will come to the United States for trial.

Officials said the hackers also took steps to cover their tracks, routing traffic through 34 servers in 20 countries to hide their location, using encrypted communication channels and wiping logs that might have given away what they were doing.

“American business cannot be complacent about protecting their data,” said FBI Deputy Director David Bowdich.

Barr said that although the Justice Department does not normally charge other countries’ military or intelligence officers outside the United States, there are exceptions, and the indiscriminate theft of civilians’ personal information “cannot be countenanced.”

In the United States, he said, “we collect information only for legitimate, national security purposes.”

None of the four is in custody, and officials acknowledged that there is little prospect they will come to the United States for trial.

But the indictment does serve as a public shaming, and officials said that if those charged attempt to travel someday, the United States could arrest them.

“We can’t take them into custody, try them in a court of law, and lock them up — not today, anyway,” Bowdich said.

“We can’t take them into custody, try them in a court of law, and lock them up — not today, anyway,” Bowdich said.

“But one day, these criminals will slip up, and when they do, we’ll be there.”

The case marks the second time the Justice Department has unsealed a criminal indictment against PLA hackers for targeting U.S. commercial interests.

The case marks the second time the Justice Department has unsealed a criminal indictment against PLA hackers for targeting U.S. commercial interests.

In 2014, the Obama administration announced an indictment against five suspected PLA hackers for allegedly breaking into the computer systems of a host of American manufacturers.

Sen. Rick Scott questions Department of Justice Inspector General Michael Horowitz during a Senate Committee On Homeland Security And Governmental Affairs.

Sen. Rick Scott questions Department of Justice Inspector General Michael Horowitz during a Senate Committee On Homeland Security And Governmental Affairs.

Ima

Ima