By Lily Kuo in Beijing Philip Oltermann in Berlin

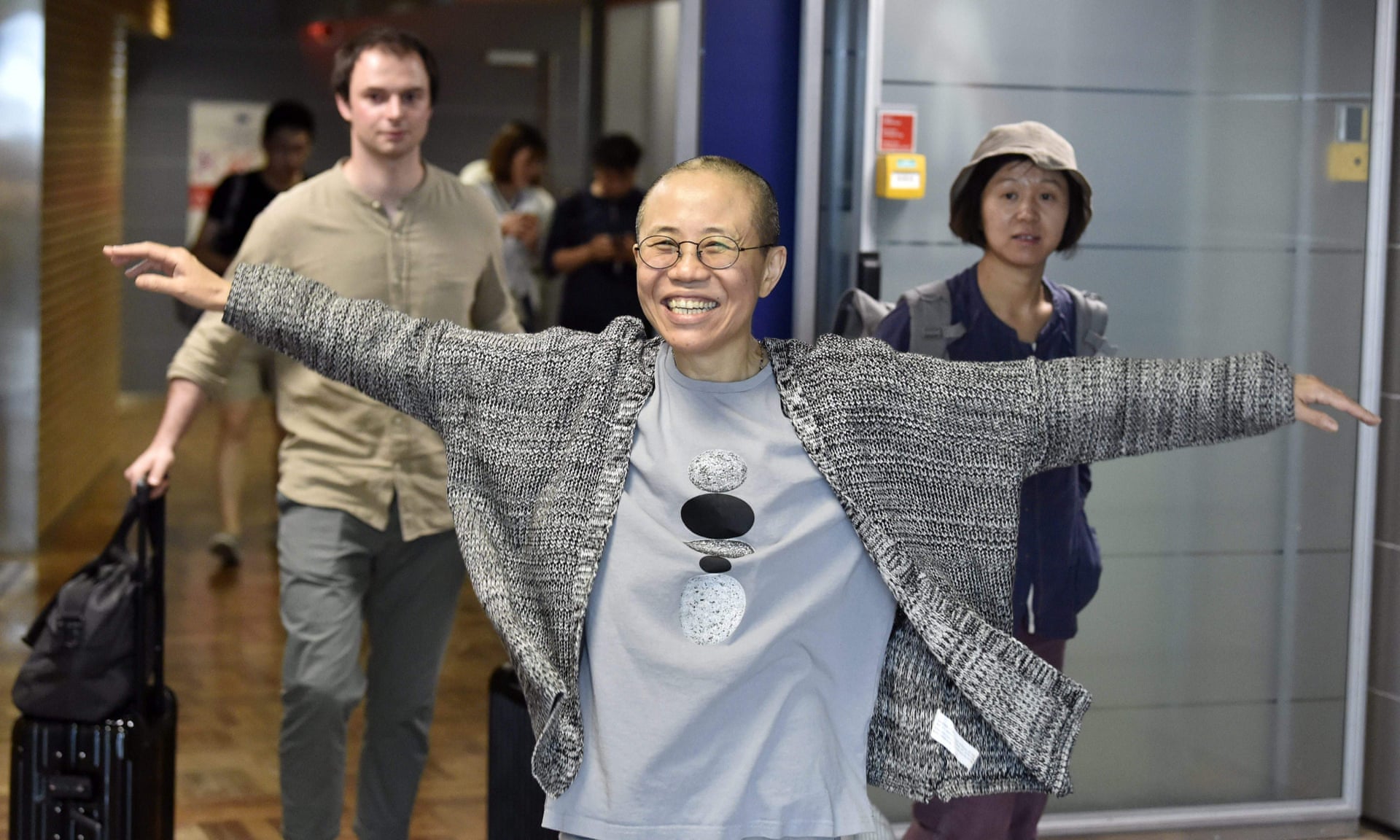

Liu Xia smiles as she arrives at Helsinki airport on her way to Berlin.

Liu Xia, the widow of the Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo, has arrived in Berlin, having left Beijing after almost eight years of living under house arrest and days before the anniversary of her husband’s death.

At 4.49pm (1539 BST) on Tuesday a Finnair flight carrying the poet and visual artist touched down at Tegel airport in the German capital, where Liu is reported to be seeking medical aid.

Human rights activists and friends of Liu had confirmed her departure from Beijing earlier on Tuesday.

According to Human Rights Watch, the German government negotiated Liu’s release.

“Ever since her late husband received the Nobel peace prize while in a Chinese prison, Liu Xia was also unjustly detained. The German government deserves credit for its sustained pressure and hard work to gain Liu Xia’s release,” said Sophie Richardson, the China director at Human Rights Watch.

Chinese authorities have insisted that Liu, who was not formally charged with any crime, has been free to move as she wishes, but her supporters say she has been under de facto house arrest.

Liu’s husband, Liu Xiaobo, was awarded the Nobel prize in 2010 for his activism in China.

“Ever since her late husband received the Nobel peace prize while in a Chinese prison, Liu Xia was also unjustly detained. The German government deserves credit for its sustained pressure and hard work to gain Liu Xia’s release,” said Sophie Richardson, the China director at Human Rights Watch.

Chinese authorities have insisted that Liu, who was not formally charged with any crime, has been free to move as she wishes, but her supporters say she has been under de facto house arrest.

Liu’s husband, Liu Xiaobo, was awarded the Nobel prize in 2010 for his activism in China.

He was jailed in 2009 for subversion, for his involvement in Charter 08, a manifesto calling for reforms.

He died last year from liver cancer while serving an 11-year prison sentence.

People wait at Berlin airport to welcome Liu Xia.

Patrick Poon, a China researcher for Amnesty International, said Liu had been allowed to leave China but her brother, Liu Hui, has had to remain in Beijing.

He was convicted on fraud charges over a real-estate dispute in 2013, a case activists believed to be retribution against the family.

“It’s really wonderful that Liu Xia is finally able to leave China after suffering so much all these years,” Poon said.

“It’s really wonderful that Liu Xia is finally able to leave China after suffering so much all these years,” Poon said.

“However, it’s worrying that her brother, Liu Hui, is still kept in China. Liu Xia might not be able to speak much for fear of her brother’s safety.”

Liu Xiaobo, Nobel laureate and political prisoner, dies at 61 in Chinese custody.

Liu Hui posted on WeChat that his sister had flown to Europe to “start her new life”.

Liu Xiaobo, Nobel laureate and political prisoner, dies at 61 in Chinese custody.

Liu Hui posted on WeChat that his sister had flown to Europe to “start her new life”.

He wrote: “I am grateful for people’s concern and assistance these past years.”

News of Liu’s release came one day after the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, met with Li Keqiang, in Bremerhaven, inviting speculation about whether the development was part of a broader diplomatic deal.

News of Liu’s release came one day after the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, met with Li Keqiang, in Bremerhaven, inviting speculation about whether the development was part of a broader diplomatic deal.

China and Germany have in recent months become the two main targets of a US president threatening trade tariffs on industrial imports.

“Is Liu Xia’s release all about softening up the German chancellor, as one of the most important representatives of the liberal industrial nations, in order to form a joint front against Trump?”, wrote the German weekly Die Zeit.

“Is Liu Xia’s release all about softening up the German chancellor, as one of the most important representatives of the liberal industrial nations, in order to form a joint front against Trump?”, wrote the German weekly Die Zeit.

“It’s an ugly suspicion, but one that can’t be dismissed out of hand.”

“Of course I am very happy that finally she’s gained her freedom and could leave China, but this does not mean China has made any improvements on human rights,” said Hu Ping, a US-based editor and friend of Liu’s.

Since last year, activists, diplomats and friends of Liu have been lobbying especially hard for her release.

Since last year, activists, diplomats and friends of Liu have been lobbying especially hard for her release.

Hu said Liu was told in May she may be able to leave in July.

Li’s visit to Germany and the signing of $23.6bn (£1.98bn) in trade deals do not seem to him to be a coincidence.

“This might be why she was able to leave now,” he said.

Another friend of Liu’s told the German news agency Dpa that Germany had been consistently lobbying for the artist’s release over the last four years and kept contact with her via its Beijing embassy.

Another friend of Liu’s told the German news agency Dpa that Germany had been consistently lobbying for the artist’s release over the last four years and kept contact with her via its Beijing embassy.

“Merkel’s visit [to China] in May was apparently crucial for the release,” the anonymous friend is quoted as saying.

Friends and advocates had been calling for Liu’s release so she could seek medical help for severe depression.

Friends and advocates had been calling for Liu’s release so she could seek medical help for severe depression.

In May the Chinese writer Liao Yiwu released a recording of a phone call in which Liu described the mental torture of her situation.

“If I can’t leave, I’ll die in my home,” she said.

One of the last times she was seen in public was in July last year, when she scattered the ashes of her late husband at sea.

One of the last times she was seen in public was in July last year, when she scattered the ashes of her late husband at sea.

While under house arrest, both of her parents died and she has been hospitalised at least twice for a heart condition.

Frances Eve, a researcher at Chinese Human Rights Defenders, said: “Hopefully she will be able to recuperate and receive much-needed medical care, but China is effectively holding her brother hostage so she may not speak out about her ordeal. The Chinese government has already shown its willingness to ruthlessly deploy collective punishment against their family.”

Frances Eve, a researcher at Chinese Human Rights Defenders, said: “Hopefully she will be able to recuperate and receive much-needed medical care, but China is effectively holding her brother hostage so she may not speak out about her ordeal. The Chinese government has already shown its willingness to ruthlessly deploy collective punishment against their family.”