By Paul Mozur and Lin Qiqing

In Hong Kong, umbrellas are commonly deployed to shield protester activities from digital eyes.

HONG KONG — There’s no sign to mark it.

But when travelers from Hong Kong cross into Shenzhen in mainland China, they reach a digital cut-off point.

On the Hong Kong side, the internet is open and unfettered.

On the Hong Kong side, the internet is open and unfettered.

On the China side, connections wither behind filters and censors that block foreign websites and scrub social media posts.

The walk is short, but the virtual divide is huge.

This invisible but stark technological wall has loomed as Hong Kong’s protests smolder into their fourth month.

This invisible but stark technological wall has loomed as Hong Kong’s protests smolder into their fourth month.

The semiautonomous city’s proximity to a society that is increasingly closed off and controlled by technology has informed protesters’ concerns about Hong Kong’s future.

For many, one fear is the city will fall into a shadow world of surveillance, censorship and digital controls that many have had firsthand experience with during regular travels to China.

The protests are a rare rebellion against Beijing’s vision of tech-backed authoritarianism.

The protests are a rare rebellion against Beijing’s vision of tech-backed authoritarianism.

Unsurprisingly, they come from the only major place in China that sits outside its censorship and surveillance.

The symbols of revolt are rife.

The symbols of revolt are rife.

Umbrellas, which became an emblem of protests in Hong Kong five years ago when they were used to deflect pepper spray, are now commonly deployed to shield protester activities from the digital eyes of cameras and smartphones.

In late July, protesters painted black the lenses of cameras in front of Beijing’s liaison office in the city.

Since then, Hong Kong protesters have smashed cameras to bits.

Since then, Hong Kong protesters have smashed cameras to bits.

In the subway, cameras are frequently covered in clear plastic wrapping, an attempt to protect a hardware now hunted.

In August, protesters pulled down a smart lamppost out of fear it was equipped with artificial-intelligence-powered surveillance software.

The moment showed how at times the protests in Hong Kong are responding not to the realities on the ground, but fears of what could happen under stronger controls by Beijing.

This week, as protesters confronted the police in some of the most intense clashes since the unrest began in June, umbrellas were opened to block the view of police helicopters flying overhead.

This week, as protesters confronted the police in some of the most intense clashes since the unrest began in June, umbrellas were opened to block the view of police helicopters flying overhead.

Some people got creative, handing out reflective mylar to stick on goggles to make them harder to film.

“Before, Hong Kong wouldn’t be using cameras to surveil citizens. To destroy the cameras and the lampposts is a symbolic way to protest,” said Stephanie Cheung, a 20-year-old university student and protester who stood nearby as others bashed the lens out of a dome camera at a subway stop last month.

“Before, Hong Kong wouldn’t be using cameras to surveil citizens. To destroy the cameras and the lampposts is a symbolic way to protest,” said Stephanie Cheung, a 20-year-old university student and protester who stood nearby as others bashed the lens out of a dome camera at a subway stop last month.

“We are saying we don’t need this surveillance.”

“Hong Kong, step by step, is walking the road to becoming China,” she said.

Hong Kong’s situation shows how China’s approach to technology has created new barriers to its goals, even as it has helped ensure the Communist Party’s grip on power.

In building a sprawling censorship and surveillance apparatus, China has separated itself from broader global norms.

“Hong Kong, step by step, is walking the road to becoming China,” she said.

Hong Kong’s situation shows how China’s approach to technology has created new barriers to its goals, even as it has helped ensure the Communist Party’s grip on power.

In building a sprawling censorship and surveillance apparatus, China has separated itself from broader global norms.

Most people — including in Hong Kong — still live in a world that looks technologically more like the United States than China, where services like Facebook, Google and Twitter are blocked.

With much of culture and entertainment happening on smartphones, China faces the challenge of asking Hong Kong citizens to give up their main way of digital life.

Protesters pulling down a smart lamppost during an anti-government rally in August.

Protesters pulling down a smart lamppost during an anti-government rally in August.

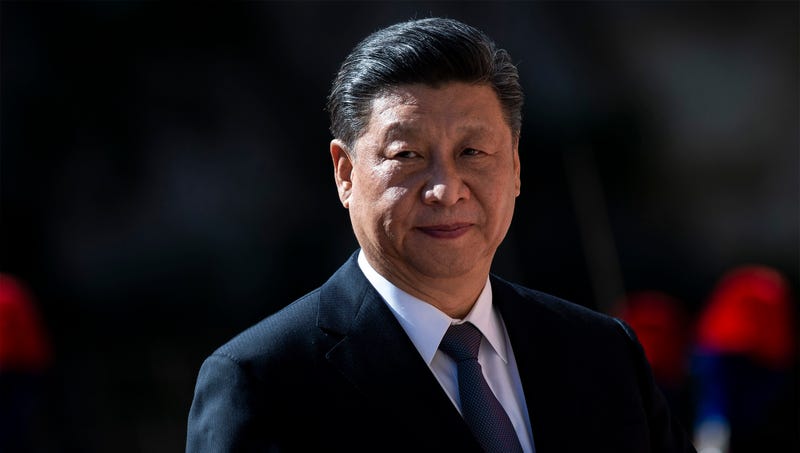

In the mainland, Xi Jinping has strengthened an already muscular tech-powered censorship and surveillance system.

The government has spent billions to knit together sprawling networks that pull from facial-recognition and phone-tracking systems.

Government apps are used to check phones, register people and enforce discipline within the Chinese Communist Party.

The internet police have been empowered to question the outspoken and the small, but significant, numbers of people who use software to circumvent the internet filters and get on sites like Twitter.

“One country, two systems” — the shorthand to describe China’s and Hong Kong’s separate governance structures — has brought with it one country, two internets.

Undoing that is an ask that is too large for many.

“One country, two systems” — the shorthand to describe China’s and Hong Kong’s separate governance structures — has brought with it one country, two internets.

Undoing that is an ask that is too large for many.

Apps like the Chinese messaging service WeChat, which some in Hong Kong use, in part to connect to people across the border, have garnered suspicion.

Gum Cheung, 43, an artist and curator who travels to China for work, said he abandoned WeChat last year after he noticed some messages he sent to friends were not getting through.

“We have to take the initiative to hold the line. The whole internet of mainland China is under government surveillance,” he said.

The Cyberspace Administration of China did not respond to a faxed request for comment about the impact of internet censorship.

“We have to take the initiative to hold the line. The whole internet of mainland China is under government surveillance,” he said.

The Cyberspace Administration of China did not respond to a faxed request for comment about the impact of internet censorship.

The Hong Kong police did not respond to questions about their use of surveillance during the protests.

Beijing’s approach has sometimes encouraged the fears.

Beijing’s approach has sometimes encouraged the fears.

In recent months, playing to a push from China’s government, Hong Kong’s airline carrier Cathay Pacific scrutinized the communications of its employees to ensure they do not participate in the protests.

Twitter and Facebook took down accounts in what they said was an information campaign out of China to change political opinions in Hong Kong.

The debate over why, how, and who watches who has at times descended into a self-serving back-and-forth between the police and protesters.

The Hong Kong police have arrested people based on their digital communications and ripped phones out of the hands of unwitting targets to gain access to their electronics.

The debate over why, how, and who watches who has at times descended into a self-serving back-and-forth between the police and protesters.

The Hong Kong police have arrested people based on their digital communications and ripped phones out of the hands of unwitting targets to gain access to their electronics.

Sites have also been set up to try to identify protesters based on their social media accounts.

More recently, the police have requested data on bus passengers to pinpoint escaping protesters.

Protesters have called for the police to release footage showing abuses at Hong Kong’s Prince Edward subway station in Kowloon in August.

Protesters have called for the police to release footage showing abuses at Hong Kong’s Prince Edward subway station in Kowloon in August.

Hong Kong’s subway operator fired back, pointing out that cameras that might have gotten the footage were destroyed by protesters.

Other than a few screenshots, they have not released footage.

“Trust in institutions is what separates Hong Kong from China,” said Lokman Tsui, a professor at the School of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

“Trust in institutions is what separates Hong Kong from China,” said Lokman Tsui, a professor at the School of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Privacy concerns on both sides have driven efforts to maintain real-life anonymity.

Police officers have stopped wearing badges with names or numbers.

Protesters have covered their faces with masks.

Both sides are carrying out increasingly sophisticated attempts to identify the other online.

Each even has a matching, if often ineffective, countermeasure to video surveillance.

Each even has a matching, if often ineffective, countermeasure to video surveillance.

Protesters shine laser pointers at lenses of police cameras to help hide themselves.

Police officers have strobing lights attached to their uniforms that can make it hard to capture their images.

“Of course we’re worried about the cameras,” said Tom Lau, 21, a college student.

“Of course we’re worried about the cameras,” said Tom Lau, 21, a college student.

“If we lose, the cameras recorded what we’ve done, and they can bide their time and settle the score whenever they want.”

“We still have decades in front of us,” he said.

“We still have decades in front of us,” he said.

“There will be a record. Even if we don’t want to work for the government, what if big companies won’t hire us?”

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/assets/2721809/theverge1_640.jpg)

Tributes to Hu, who protesters called

Tributes to Hu, who protesters called