The new documentary ‘One Child Nation’ examines China’s draconian, decades-long one-child policy, which resulted in countless abductions, forced abortions, and child deaths.

By Nick Schager

One Child Nation is a stark reminder that America isn’t the only country where a woman’s right to control her body has been under siege.

One Child Nation is a stark reminder that America isn’t the only country where a woman’s right to control her body has been under siege.

Winner of the Grand Jury Prize at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, and premiering in select theaters on August 9 courtesy of Amazon, directors Nanfu Wang and Jialing Zhang’s heartrending documentary examines their native China’s one-child policy, which functioned as a systematic attack on its female population—and which resulted in collateral damage on an international scale.

In effect from 1979 to 2015, China’s policy placed strict guidelines on reproduction in order to curb population growth, which Wang’s mother proclaims (parroting the Communist Party line) might otherwise have led to famine and potential cannibalism.

In effect from 1979 to 2015, China’s policy placed strict guidelines on reproduction in order to curb population growth, which Wang’s mother proclaims (parroting the Communist Party line) might otherwise have led to famine and potential cannibalism.

Urban citizens were limited to a single child, while rural inhabitants were, in the mid-1980s, granted the opportunity to have a second kid.

The law outlined strict punishment for non-compliance: the destruction of homes, forfeiture of property and valuables, and steep fines.

Those who suffered those penalties, however, got off easy, since local Family Planning Officials—empowered by the Communist Party—also had the authority to abduct women, tie them up, and force them to undergo sterilizations and abortions as late as eight to nine months into their pregnancies.

As the filmmakers detail in a series of stunning conversations with residents of Wang’s hometown (and similar provinces), those procedures entailed murdering infants after they’d been born.

As the filmmakers detail in a series of stunning conversations with residents of Wang’s hometown (and similar provinces), those procedures entailed murdering infants after they’d been born.

Artist Peng Wang presents photos of discarded fetuses he found in trash dumps, wrapped in yellow “medical waste” bags, as well as one deceased newborn that he kept in a formaldehyde-filled jar. Even in a doc rife with horror stories, these images are difficult to shake, underlining the unthinkably callous consequences of a strategy that the Chinese government proclaimed would double everyone’s standard of living.

Wang and Zhang’s film was motivated by the birth of the former’s son, as well as her upbringing in China (she emigrated at age 26 to the U.S., where she had her first baby).

Rather than a straightforward textbook overview of the policy, One Child Nation is also a memory piece.

Narrating action that’s been partly structured as an investigation into both her—and her family’s—past, Wang relies heavily on recollections about growing up during this propaganda-saturated period, when billboards, TV programs, and theatrical and music performances touted the policy as the means by which the country would forge a glorious path into the future, providing prosperity, unity and happiness for all who obeyed.

Alongside such heartening messages were pervasive spray-painted signs and children’s ditties that threatened nonconformists.

Alongside such heartening messages were pervasive spray-painted signs and children’s ditties that threatened nonconformists.

For a population still reeling from the hardships of prior decades, and trained from birth to accept the Party as infallible and the master of people’s fate, abiding by these rules was difficult but not impossible.

Anecdotes about women fighting back against forced abortions are occasionally heard in One Child Nation.

Yet far more prevalent are tales about babies being placed in baskets and left on the side of the road or at markets, to be snatched up by passersby or, as was more often the case, to die of starvation and exposure.

That was going to be the fate of Wang’s brother until he turned out to be a boy—a micro example of the macro sexism that dominates China, where sons are prized for carrying on the family name, and daughters are thought of as expendable secondary figures destined to desert their clans (by marrying into other families).

That was going to be the fate of Wang’s brother until he turned out to be a boy—a micro example of the macro sexism that dominates China, where sons are prized for carrying on the family name, and daughters are thought of as expendable secondary figures destined to desert their clans (by marrying into other families).

In that environment, disposing of female infants was no big deal—not that China stopped there.

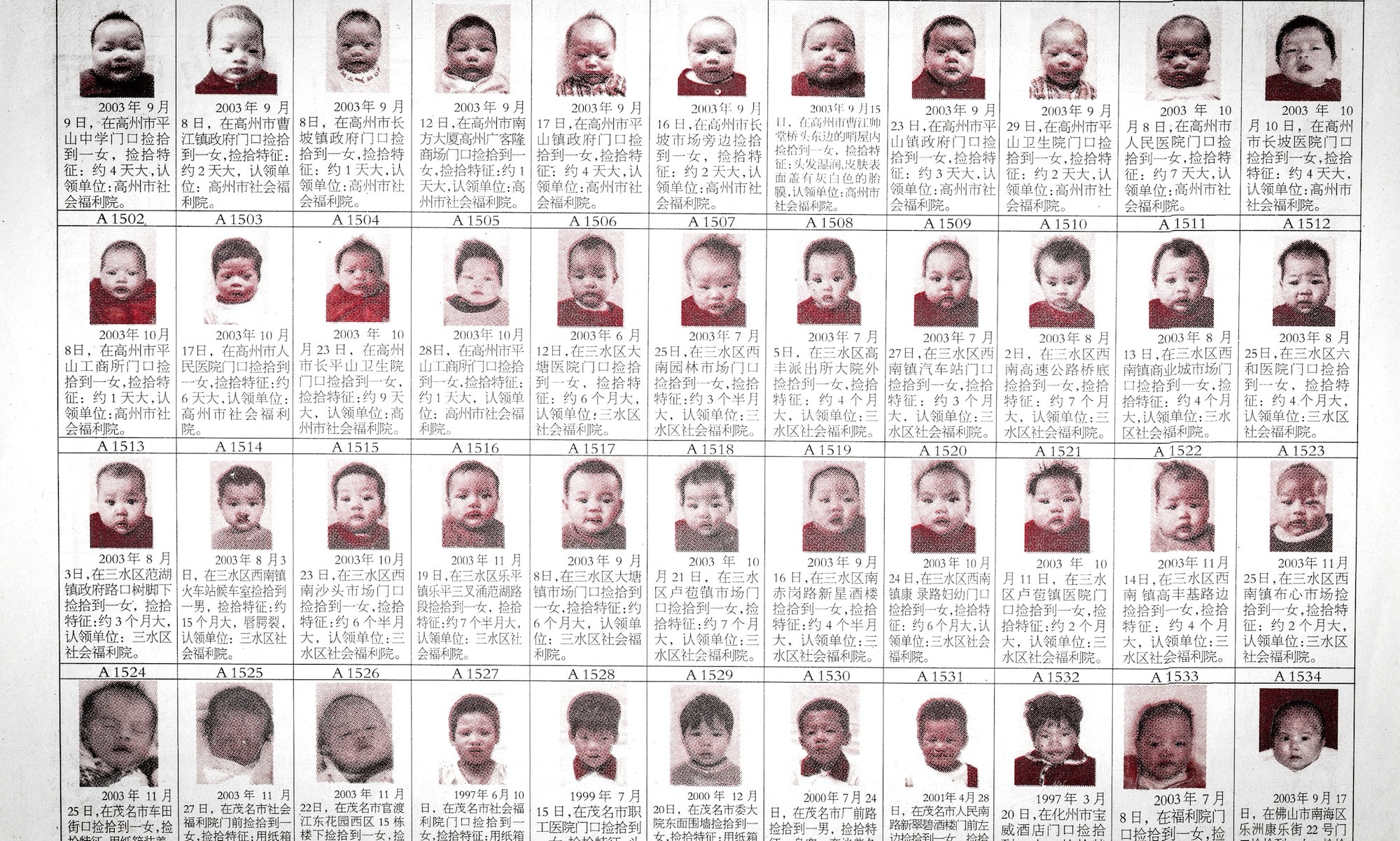

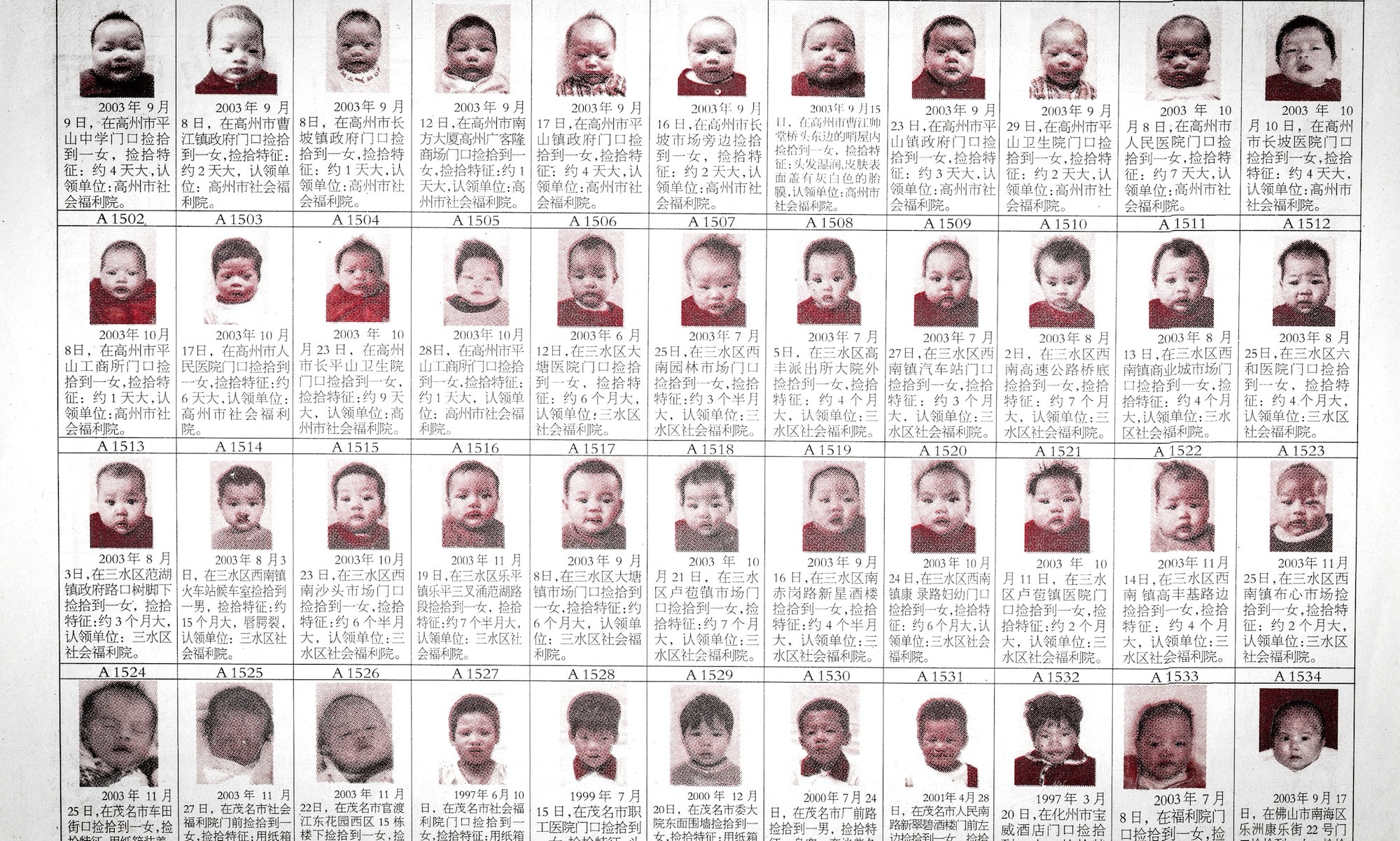

In the early 1990s, the country began allowing foreigners to adopt “orphans,” thereby creating a booming market for Chinese girls.

What Wang and Zhang reveal is that overseas adoption quickly became a despicable trafficking racket in which Family Planning officials tore second children away from their homes and gave them to orphanages (for a fee), which then sold them to American and European families who ostensibly had no clue that they were perpetuating a kidnapping-for-profit paradigm.

In vignettes with Brian Stuy and Long Lan Stuy, the American parents of three adopted Chinese girls and the founders of Research China—an organization that identifies and reunites kids with their birth parents—One Child Nation lays out the extent to which the one-child policy victimized just about anyone who came into contact with it.

In vignettes with Brian Stuy and Long Lan Stuy, the American parents of three adopted Chinese girls and the founders of Research China—an organization that identifies and reunites kids with their birth parents—One Child Nation lays out the extent to which the one-child policy victimized just about anyone who came into contact with it.

That includes Wang herself, who expresses guilt over having been a patriotic youngster while one of her aunts was sending her cousin away with traffickers, and another uncle was leaving his daughter in the street to perish.

For Wang, the film is a personal reckoning with traumatic history—a process also being undertaken by some of her policy-complicit interviewees, including a doctor who claims to have performed between 50,000 and 60,000 abortions and sterilizations, and now atones for her sins by running an infertility clinic.

With speakers habitually explaining their acquiescence to the one-child policy by claiming that they “had no choice,” One Child Nation proves a portrait of powerlessness in the face of an authoritarian government that demanded blind obedience, and didn’t care about the human wreckage caused by its demands.

With speakers habitually explaining their acquiescence to the one-child policy by claiming that they “had no choice,” One Child Nation proves a portrait of powerlessness in the face of an authoritarian government that demanded blind obedience, and didn’t care about the human wreckage caused by its demands.

Wang and Zhang craft their material as a chronological journey, each step uncovering ever-more-depressing realities, and it culminates with a poignant passage about a young girl who was denied an adolescence with her twin sister after the latter was taken from their home and, shortly thereafter, adopted by Americans.

In this young girl’s countenance, growing sadder as she contemplates the gulf between her and her stateside sibling—whom she’s connected with over social media, albeit in a casual, detached manner—Wang locates a profound sorrow that dovetails with her own feelings about the relatives she lost to the one-child policy.

In this young girl’s countenance, growing sadder as she contemplates the gulf between her and her stateside sibling—whom she’s connected with over social media, albeit in a casual, detached manner—Wang locates a profound sorrow that dovetails with her own feelings about the relatives she lost to the one-child policy.

One Child Nation’s coda reveals that the country now touts a two-child policy as the key to continued success.

But in light of all that’s come before it, that notion feels like nonsense aimed at masking a continued top-down desire to regulate every facet of women’s lives.