By Yu Hua

Souvenirs featuring portraits of Mao Zedong and Xi Jinping, Beijing.

When I try to describe how

China has changed over the past 50 years, countless roads appear in front of me.

Given the sheer immensity of these changes, all I can do is try first to follow a couple of main roads, and then a few smaller ones, to see where they take us.

My first main road begins in the past.

In my 58 years, I have experienced three dramatic changes, and each one has been accompanied by a surge in suicides among officials.

The first time was during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966.

At the start of that period, many members of the Chinese Communist party woke up one day to find they had been purged: overnight they had become “power-holders taking the capitalist road”.

After suffering every kind of psychological and physical abuse, some chose to take their own lives.

In the small town in south China where I grew up, some hanged themselves or swallowed insecticide, while others threw themselves down wells: wells in south China have narrow mouths, and if you dive into one headfirst, there is no way you will come out alive.

In the early stages of the Cultural Revolution, many people from the lowest tiers of society formed their own mass organisations, proclaiming themselves commanders of a “Cultural Revolution headquarters”.

These individuals – rebels, they were called – often went on to secure official positions of one kind or another.

They enjoyed only a brief career, however.

Following Mao’s death in 1976, the subsequent end of the Cultural Revolution and the emergence of the reform-minded Deng Xiaoping as China’s new leader, some rebels believed they would suffer just as much as the officials they had tormented a few years before.

Thus came the second surge in suicides – this time of officials who had clawed their way to power as revolutionary radicals.

One official in my little town drowned himself in the sea: he smoked a lot of cigarettes first, and the stubs littering the shore marked the agony of indecision that preceded his death.

This was a much smaller surge in suicides than the first one, because Deng was not out for political revenge, focusing instead on kickstarting economic reforms and opening up to the west.

This policy led in turn to China’s economic miracle, the downside of which has been

environmental pollution, growing inequality and pervasive corruption.In late 2012 came the third dramatic change in my lifetime, when China entered the era of

Xi Jinping.

No sooner did Xi become general secretary of the Communist party than our new leader launched an anti-corruption drive, the scale and force of which took almost everyone by surprise.

The third surge in suicides followed.

When officials who had stuffed their pockets during China’s breakneck economic rise discovered they were being investigated and realised they could not wriggle free, some put an end to things by suicide.

In cases involving lower-ranking officials who were under investigation but had not yet been taken into custody, the government explanation was that their suicides were triggered by depression.

But, if a high-ranking official took his own life, a harsher judgment was passed.

On 23 November 2017, after Zhang Yang, a general, hanged himself in his own home, the People’s Liberation Army Daily reported that he “had evaded party discipline and the laws of the nation” and described his suicide as “a disgraceful action”.

These three surges in suicide demonstrate the failure and impotence of legal institutions in China.

The public security organs, prosecutorial agencies and courts all stopped functioning at the start of the Cultural Revolution; thereafter, laws existed only in name.

Since Mao’s death, a robust legal system has never truly been established and, today, law’s failure manifests itself in two ways.

First, the law is strong only on paper: in practice, law tends to be subservient to the power that officials wield.

Second, when officials realise they are being investigated and know their position won’t save them, some will choose to die rather than submit to legal sanctions, for officials who believe in power don’t believe in law.

These two points, seemingly at odds, are actually two sides of the same coin.

The difference between the three surges in suicide is this: the first two were outcomes of a political struggle; framed by the start and the end of the Cultural Revolution.

The third, by contrast, stems from the blight of corruption that has accompanied 30 years of rapid economic development.

Of course, the anti-corruption campaign is conducted selectively, with the goal of purging Xi Jinping’s political opponents.

And the underlying problem is: how many officials are there today who are truly clean?

A few years ago, an official from China’s prosecutorial agencies put it to me this way: “If you were to stick all of today’s officials in a line and shoot every one of them, that would be unfair to some. But a lot would slip through the net if you only shot every other one.”

When I turn onto the second main road that stretches from the China of my childhood to the present day, what I see before me is the declining importance of the family and the growing importance of individualism.

In Mao’s China, the individual could find no fulfilment in ordinary social life.

If one wanted to express a personal aspiration, the only way to do so was to throw oneself into a collective movement such as the Great Leap Forward or the Cultural Revolution.

Mind you, in those grand campaigns, the individual’s aspirations had to conform entirely to whatever the “correct” political line happened to be at that moment – the slightest deviation would cause disaster.

To use an analogy current at the time, each of us was a little drop of water, gathered into the great flood of socialism.

But it wasn’t so easy to be that drop of water.

In my town, there was a Cultural Revolution activist who would almost every day be at the forefront of some demonstration or other, often being first to raise his fist and shout “Down with Liu Shaoqi!” (Liu, nominally the head of state, had just been purged.)

One day, however, he inadvertently misspoke, shouting “Down with Mao Zedong!” instead.

Within seconds he had been thrown to the ground by the “revolutionary masses”, and thus he began a wretched phase in life, denounced and beaten at every turn.

In that era, the individual could find space only in the context of family life – any independent leanings could only be expressed at home.

That is why family values were so important to Chinese people then, and why marital infidelity was seen as so intolerable.

If you were caught having an extramarital affair, the social morality of the day meant that you would be subjected to all kinds of humiliation: you might be paraded through the streets with half your hair shaved off or packed off to prison.

During the Cultural Revolution, there were certainly cases of husbands and wives denouncing each other and fathers and sons falling out, but these were not typical – the vast majority of families enjoyed unprecedented solidarity.

A friend of mine told me her father had been a professor at the start of the Cultural Revolution, while her mother was a housewife.

Her father, born to a landlord’s family, became the target of attacks, but her mother, from a humbler background, was placed among the revolutionary ranks.

Pressed by the radicals to divorce her father, her mother outright refused – and not only that: every time her father was hauled off to a denunciation session, she would make a point of sitting in the front row and, if she saw someone beating her husband, she would rush over and start hitting back.

Such brawls might leave her bruised and bleeding, but she would sit back down proudly in the front row, and the radicals lost their nerve and gave up beating her husband.

After the Cultural Revolution ended, my friend’s father told her, with tears in his eyes, that had it not been for her mother he might well have taken his own life.

There are many such stories.

After Mao’s death, the economic reforms under Deng Xiaoping brought dramatic changes to China, changes that permeated all levels of Chinese society.

In a matter of 30 years, we went from one extreme to another, from an era where human nature was suppressed to an era where human impulses could run riot, from an era when politics was paramount to an era when only money counts.

Before, limited by social constraints, people could feel a modicum of freedom only within the family; with the loss of those constraints, that modest freedom which was once so prized now counts for little.

Extramarital affairs have become more and more widespread and are no longer a cause for shame.

It is commonplace for successful men to keep a mistress, or sometimes multiple mistresses – which people often jokingly compare to a teapot needing at least four or five cups to make a full tea set.

In one case I know of, a wealthy businessman bought all 10 flats in the wing of an apartment complex.

He installed his legally recognised wife in one flat, and his nine legally unrecognised mistresses in the other flats, one above the other, so that he could select at his pleasure and convenience on which floor of the building he would spend the night.

Having taken a couple of main roads that trace China’s journey over the past half-century, it is time to travel down some smaller ones.

The first begins with Buddhist temples.

During the Cultural Revolution, temples were closed down and some suffered serious damage.

In my little town, Red Guards knocked off the heads and arms of every Buddhist sculpture in the local temples, which were then converted into storehouses.

Afterwards, the damaged temples were restored and they all reopened, typically with two round bronze incense burners in front of the main hall: the first to invoke blessings for wealth, the second to invoke blessings for security.

When I visited temples in the 1980s, in the first censer I would often see a huge assembly of joss sticks, blazing away furiously, while in the second, a paltry handful would be smoking feebly.

In those days China was still very poor, and, as most people saw it, when you didn’t have money, being safe didn’t amount to much.

Now China is rich, and when you go into a temple you see joss sticks burning just as brightly in the security censer as in the wealth one – it is when you are rich that security acquires particular importance.

In China today, Buddhist temples are crowded with worshippers, while Taoist temples are largely deserted.

A few years ago, I asked a Taoist abbot: “Taoism is native to China, so why is it not as popular as Buddhism, which came here from abroad?”

His answer was short: “Buddhism has money and Taoism doesn’t.”

His explanation, although it rather took me aback, expresses a truth about Chinese society: money, or material interest, has become the main motivating force.

In the 1980s, there was a series of student protests in China, culminating in the Tiananmen demonstrations of 1989, when not just students but city dwellers all across the country joined the rallies.

Back then, the demonstrations were largely motivated by concern for the fate of the nation and a desire to see democratic freedoms put in place.

Today, people still demonstrate, but on a very small scale, and these demonstrations – “mass incidents” in official parlance – are completely different from the protests in the 1980s.

Protests today are not geared towards transforming society – they are simply designed to protect the material interests of the group involved.

A few years ago, in the eastern province of Jiangsu, the education authorities announced that universities would be reserving more places for students from poor areas in west China.

This triggered an uproar among the parents of Jiangsu high-school students preparing for the university entrance examination.

Concerned that this new policy would reduce their children’s chances of getting into university, they marched in the streets to protest.

Something similar happened a few years ago in Shanghai, when retirees took to the streets, worried that if welfare funds were allocated to poor areas, their own retirement benefits would be slashed.

These constant “mass incidents”, I should point out, reflect real issues.

In recent years, for instance, many retired military veterans have gathered together across the country in protests against the stingy benefits and pensions they receive from the state.

Back in the 1980s, they argue, veterans used to be more generously rewarded, relative to the cost of living.

Today, even though China is richer, they receive little.

Unsurprisingly, veterans feel shortchanged and disrespected.

In numerous industries, it has become common practice to try to secure more business by pushing down prices as low as they can possibly go.

I was struck by this new reality a few years ago, at the end of a trip I had taken to South Africa for the World Cup.

At the airport, I bought a vuvuzela in the airport as a souvenir, paying more than 100 yuan (£11).

It was only when I got back to Beijing that I realised it was made in China.

At the start, Chinese manufacturers had set their factory price at over five yuan a piece, but they soon found themselves being underbid.

Some factories ultimately set their price as low as 2.2 yuan, when the production cost was 2 yuan per unit.

The result of all this ferocious competition is that the profit margin keeps getting slimmer and slimmer, and those who suffer most are ordinary workers, who often see no increase in their salary even as their work hours are extended.

Now I need to take two other roads – the road of innovation and the road of nostalgia.

Innovation first.

Given the speed at which new technologies become dominant, you sometimes feel that there is no gap at all between new and old.

Take mobile payments: in the space of just a few years, Alibaba’s Alipay mobile app and Tencent’s WeChat Pay app have been loaded on to practically every smartphone in the country.

From big shopping malls to little corner shops – any place where a transaction can be made will have the scannable QR codes for these two payment platforms displayed in a prominent location.

People just need to take their phone out of their pocket, do a quick scan and the payment is made. Even Chinese beggars have to keep up with the times: sometimes they too have a QR code handy, and they will ask passersby to scan it and use the mobile payment platform to dispense some spare change.

I recently went for more than a year without using cash or a credit card, because it is just so convenient to pay by phone instead.

This July, though, when my English translator came to Beijing and my wife and I took him out for dinner, I went to scan the restaurant’s QR code but the transaction failed to go through.

Instead of trying a second time, I suddenly felt an urge to pay in cash.

When I pulled some banknotes out of my pocket, handed them to the cashier and received change in return, I felt a pleasant tingle of novelty.

This novelty is all the more remarkable given that just 30 years ago, when Chinese people went on business trips, they would worry so much about their money being stolen that they would hide cash in their underpants, the safest place for it.

They would have a little pocket sewn on the inside, with a button for extra security.

When a bill needed to be paid they would reach a hand into their underwear, grope around a bit, and pull out the requisite five-mao or one-yuan note, distinguishable by feel because one was smaller than the other.

Women would withdraw to a secluded spot to retrieve their cash, but some men would have no such inhibitions and would rummage about in their underpants quite unabashedly.

When I turn to the road of nostalgia, I think of how my home county of Haiyan has transformed. When I was a boy, Haiyan had a total population of 300,000, with only 8,000 living in the county town itself.

Now, the county has a population of 380,000, of whom 100,000 live in the county seat.

Urbanisation has created a lot of problems, one of them being what happens after farmers move to cities.

Local governments have expropriated large swathes of agricultural land to enable an enormous urban expansion program: some of the land is allocated to industry in order to attract investment, build factories and boost government revenues, but most of it is sold off at a high price to real-estate developers.

The result is that high-rise apartment buildings now sprout in profusion where once only crops grew. After their land and houses in the countryside are expropriated, farmers “move upstairs” into housing blocks that the local government has provided in compensation.

In wealthy counties, some farmers may be awarded up to three or four apartments, in which case they will live in one and rent out the other two or three; others may receive a large cash settlement.

But the questions then become: how do they adjust to city life?

Now disconnected from the form of labour to which they were accustomed, what new jobs are there for them to do?

Some drive taxis and some open little shops, but others just loaf around, playing mahjong all day, and others take to gambling and lose everything they have.

Every time a community of dispossessed farmers settles into a new housing project, gambling operations will follow them there, because some of the residents will be flush with cash after the government payouts.

In China, it is forbidden to open gambling establishments, but this doesn’t stop unlicensed operators from cramming their gambling accessories into a few large suitcases and lugging them around these new neighbourhoods, where they will talk their way into the homes of resettled farmers.

The gambling outfits play hide-and-seek with the police, setting up shop here today, shifting to a new spot tomorrow.

What is the situation back where the farmers came from – the houses in the countryside now expropriated but yet to be demolished?

Peasants often have dogs to protect the home and guard the property.

When peasants move to the cities, they no longer need guard dogs, so they leave them behind.

And so you see poignant scenes in those empty, weed-infested farm compounds, as those abandoned dogs, all skin and bones, faithfully continue to perform sentry duty, now rushing from one end of the property to the other, standing on a high point and gazing off into the distance, their eyes burning with hope, longing for the past to return.

Wishing the past could return is a mood that is spreading through today’s society.

Two patterns are typical.

The more widespread of the two reflects the yearnings of the poor.

China’s enhanced status as the world’s second largest economy has brought them few benefits; they continue to lead a life of grinding hardship.

They cherish their memories of the past, for although they were poor then, the word “unemployed” was yet to exist.

What’s more, in those days there was no moneyed class in a real sense: Mao’s monthly salary, for example, was just 404.8 yuan, compared to my parents’ joint income of 120 yuan.

There was only a small gap between rich and poor, and social inequalities were limited.

A different form of nostalgia is prevalent among successful people who, having risen as high as they can possibly go, now find themselves in danger of tumbling off the cliff.

Someone reported to me an exchange he had had with one of Shanghai’s ultra-rich, a man who had relied on bribery and other underhand methods to transform himself from a pauper into a millionaire. Realising he would soon be arrested and anticipating a long prison term, he stood in front of the floor-to-ceiling windows of his huge, lofty, luxurious office and looked down at the construction workers far below, busy building the foundation of another skyscraper.

How he wished he could be one of those workers, he said, for though their work was hard and their pay was low, they didn’t have to live in a state of such high anxiety.

Faced with the prospect of losing everything they have gained, such people find themselves wishing their spectacular career hadn’t happened at all, wishing they could reclaim the past.

If the past were really to return – that past where you needed grain coupons to buy rice, oil coupons to buy cooking oil, cotton coupons to buy cloth, that past of dire material shortages, where the supply of goods was dictated by quotas – would those people who hanker for the past be happy?

I doubt it.

As I see it, when the poor pine for the past, this is not a rational desire – it is simply a way of venting their feelings, the voicing of a frustration that is rooted in their discontent with current Chinese realities.

And when that other, smaller group of people who have been successful in government or business realise they are going to spend the rest of their life behind bars and wish they could reclaim the past, this sentiment springs only from a wistful regret: “If I had known this was going to happen, I wouldn’t have got myself into this mess.”

I’m reminded of a joke that’s been doing the rounds.

Here is what’s unfair about this society:

The pretty girl says: “I want a diamond ring!” She gets it.

The rich guy says: “I want a pretty girl!” He gets her.

I say: “I want a shower!” But there’s no water.

That last situation, I myself have experienced.

In my early years, more often than not, water would cut off just as I was having a shower – sometimes at the precise moment when I had lathered myself in soap from head to toe.

All I could do then was hammer on the pipe with my fists, at the same time raising my head so that the final few drops of water would rinse my eyes and save them from smarting; as for when the water would come on again, I could only wait patiently and hope heaven was on my side.

Back then, nobody would have seen water stoppages at shower-time as a social injustice, because in those bygone days, there were no rich guys, and so pretty girls didn’t get diamond rings and rich guys didn’t get pretty girls.

It is often said that children represent the future.

In closing, let me try to capture the changing outlook of three generations of Chinese boys as a way of mapping in simple terms China’s trajectory over the years.

If you asked these boys what to look for in life, I think you would hear very different answers.

A boy growing up in the Cultural Revolution might well have said: “Revolution and struggle.”

A boy growing up in the early 1990s, as economic reforms entered their second decade, might well have said: “Career and love.”

Today’s boy might well say: “Money and girls.”

Students wave copies of Mao Zedong’s Little Red Book at the start of the Cultural Revolution, Beijing, 1966.

Students wave copies of Mao Zedong’s Little Red Book at the start of the Cultural Revolution, Beijing, 1966.  A reconstructed traditional shopping street in Beijing, 2008.

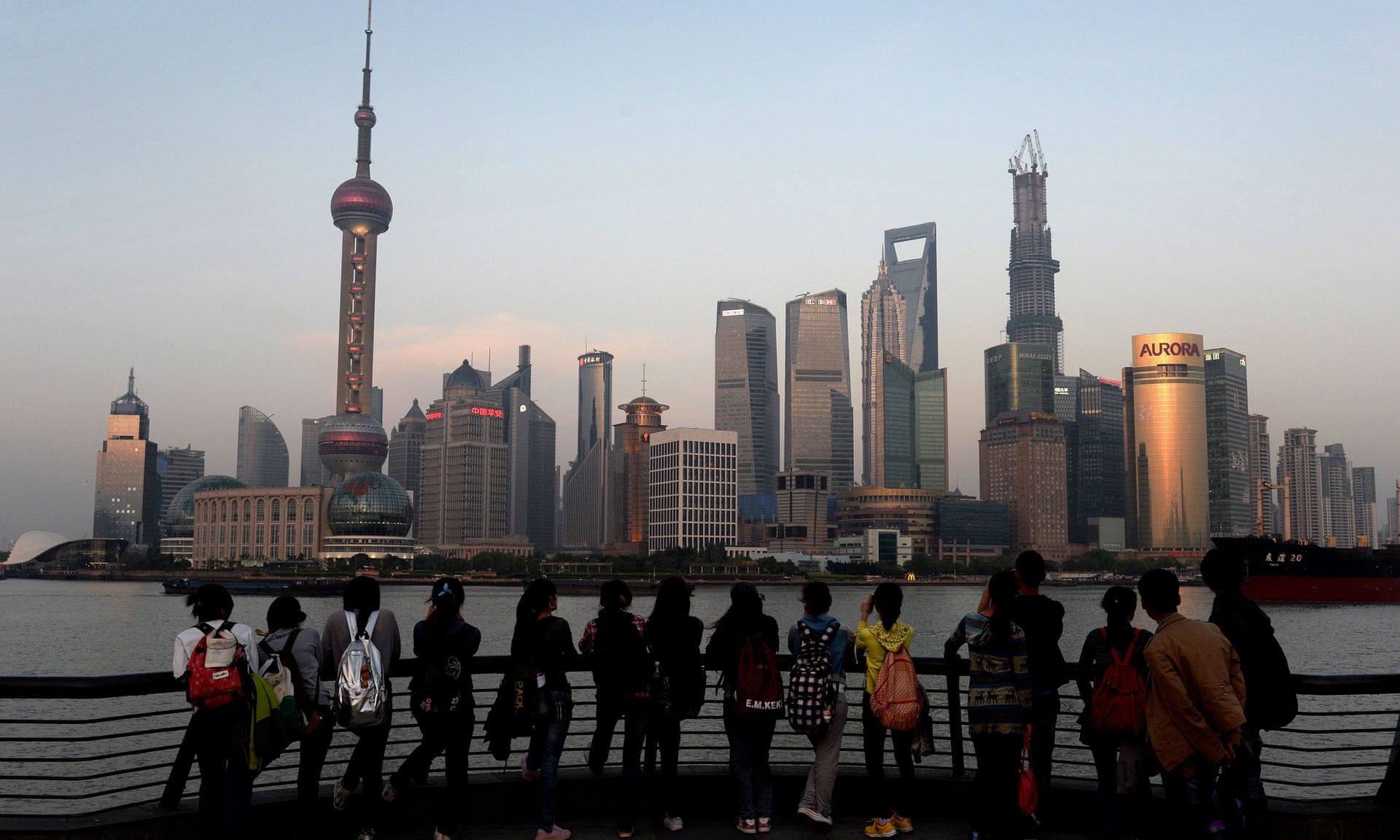

A reconstructed traditional shopping street in Beijing, 2008.  Shanghai’s Pudong financial district, 2013.

Shanghai’s Pudong financial district, 2013.

Members of a military honor guard prepare for a welcome ceremony for Kazakhstan’s President Nursultan Nazarbayev, outside the Great Hall of the People, in Beijing, on June 7. In an effort to combat the “peace disease,” the Chinese People’s Liberation Army has stepped up its efforts to improve battle readiness.

Members of a military honor guard prepare for a welcome ceremony for Kazakhstan’s President Nursultan Nazarbayev, outside the Great Hall of the People, in Beijing, on June 7. In an effort to combat the “peace disease,” the Chinese People’s Liberation Army has stepped up its efforts to improve battle readiness. Members of China’s military honor guard march during a welcome ceremony for Kazakhstan’s President Nursultan Nazarbayev, outside the Great Hall of the People, in Beijing, on June 7.

Members of China’s military honor guard march during a welcome ceremony for Kazakhstan’s President Nursultan Nazarbayev, outside the Great Hall of the People, in Beijing, on June 7.

The Hambantota Port gets only a small percentage of Sri Lanka’s port business, overshadowed by the main complex in the capital.

The Hambantota Port gets only a small percentage of Sri Lanka’s port business, overshadowed by the main complex in the capital. Sri Lankan workers processing cars being unloaded from a ship at Hambantota Port.

Sri Lankan workers processing cars being unloaded from a ship at Hambantota Port. An expressway extension to Hambantota Port. Chinese analysts have not given up the view that the port could become profitable.

An expressway extension to Hambantota Port. Chinese analysts have not given up the view that the port could become profitable. The Mahinda Rajapaksa International Cricket Stadium in Hambantota. The stadium has more seats than the population of the area’s main town.

The Mahinda Rajapaksa International Cricket Stadium in Hambantota. The stadium has more seats than the population of the area’s main town. Pilgrim monks visiting the largely empty Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport, just 150 miles southeast from the country’s main airport.

Pilgrim monks visiting the largely empty Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport, just 150 miles southeast from the country’s main airport.

Harvesting rice in a field where the industrial area is due to be built.

Harvesting rice in a field where the industrial area is due to be built. Chinese construction workers, bottom left, walking home from work in front of Colombo’s changing skyline.

Chinese construction workers, bottom left, walking home from work in front of Colombo’s changing skyline. China Harbor employees heading to work in Colombo.

China Harbor employees heading to work in Colombo. Chinese workers in their dormitory in Colombo.

Chinese workers in their dormitory in Colombo. The Port of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

The Port of Colombo, Sri Lanka. The Colombo Port City development.

The Colombo Port City development.