Hong Kong young demonstrators shift back and forth between their old lives and their new ones– school uniforms and dinners with mom and dad, then pulling the masks over their faces once more.

By TOM LASSETER

Fiona’s rebellion against the People’s Republic of China began slowly in the summer months, spreading across her 16-year-old life like a fever dream.

The marches and protests, the standoffs with police, the lies to her parents.

They’d all built on top of her old existence until she found herself, now, dressed in black, her face wrapped with a homemade balaclava that left only her eyes and a pale strip of skin visible.

Her small hands were stained red.

It was just paint, she said, as she funneled liquid into balloons.

The air around her stank of lighter fluid.

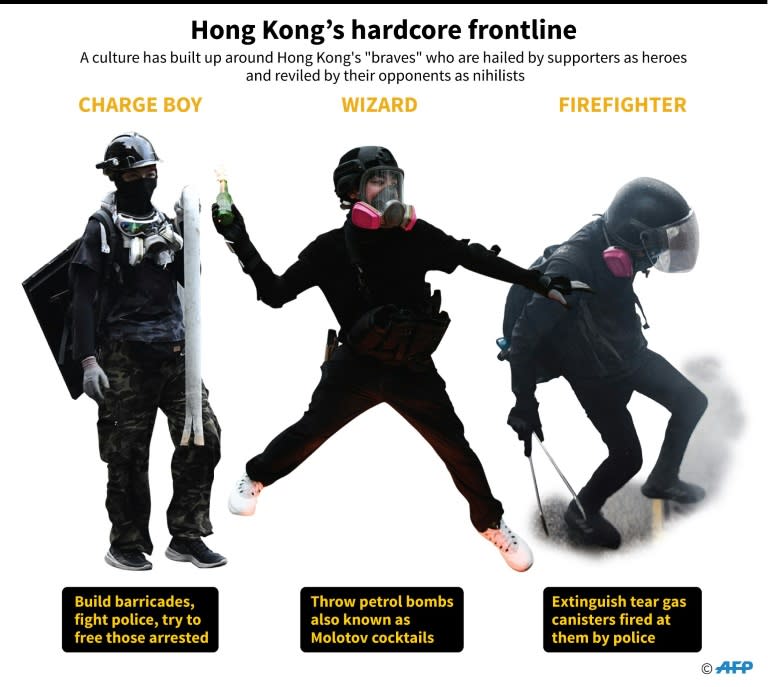

Teenagers hurled Molotov cocktails toward police.

Lines of archers roamed the grounds of the university they’d seized; sometimes, they stopped to release metal-tipped arrows into the darkness, let fly with the hopes of finding the flesh of a cop.

Down below Fiona, rows of police flanked an intersection.

Within a stone’s throw, Chinese soldiers stood in riot gear behind the gates of an outpost of the People’s Liberation Army, one of the most powerful militaries on the planet.

Fiona joined her first march on June 9, a schoolgirl making her way to the city’s financial district on a sunny day as people called out for freedom.

It was now November 16, and she was one of more than 1,000 protesters swarming around and barricaded inside Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Because of their young age and the danger of arrest, Reuters is withholding the full names of Fiona and her comrades.

Night was falling.

They were wild and free with their violence, but on the verge of being surrounded and pinned down.

The kids, which is what most of them were, buzzed back and forth like hornets, cleaning glass bottles at one station, filling them with lighter fluid and oil in another.

An empty swimming pool was commandeered to practice flinging the Molotov cocktails, leaving burn marks skidded everywhere.

When front-line decisions needed to be made, clumps of protesters came together to form a jittering black nest – almost everyone was dressed from hood to mask to pants in black – yelling about whether to charge or pull back.

A protester stands in front of smashed windows and graffiti saying “Liberty or Death” during the standoff at Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

A protester stands in front of smashed windows and graffiti saying “Liberty or Death” during the standoff at Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

They were becoming something different from what they were, a metamorphosis that would have been difficult to imagine in orderly Hong Kong, a city where you line up neatly for an elevator door and crowds don’t step into an empty street until the signal changes.

With each slap up against the police, each scramble down the subway stairs to avoid arrest as tear gas ate at their eyes, they hardened.

They shifted back and forth between their old lives and their new – school uniforms and dinners with mom and dad, then pulling the masks over their faces once more.

It was a dangerous balance.

“We may all be killed by the police. Yes,” said Fiona.

At the crucible of Polytechnic University, Fiona and the others crossed a line.

Their movement has embraced the slogan of “be water,” of pushing forward with dramatic action and then pulling back suddenly, but here, the protesters hunkered down, holding a large chunk of territory in the middle of Hong Kong.

In doing so, Fiona found moments bigger than what her life was before.

“We call the experience of protest, like at PolyU, a dream,” she later explained.

But to speak of such things out loud, without the mask that she hid behind, without the throbbing crowds that made it seem within reach, is not possible outside, in the real Hong Kong.

The protesters have left traces of their hopes, confessions and fears across the city, in graffiti scrawled on bank buildings and bus stops alike.

One line that’s appeared: “There may be no winners in this revolution but please stay to bear witness.”

The impact of Hong Kong’s protests, as they pass the half-year mark, is this: Kids with rocks and bottles have fought their way to the sharp edge between two nation states expected to shape the 21st century.

The street unrest resembles an ongoing brawl between police and the young men and women in black.

Police have fired about 16,000 rounds of tear gas and 10,000 rubber bullets.

Since June, they’ve rounded up people from the ages of 11 to 84, making more than 6,000 arrests.

About 500 officers have been wounded in the melee.

After the U.S. Congress was galvanized by the plight of the protesters, it passed the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, which President Donald Trump signed last month.

The law subjects Hong Kong to review by the U.S. State Department, at least once a year, on whether the city has clung to enough autonomy from Beijing to continue receiving favorable trading terms from America.

It also provides for sanctions, including visa bans and asset freezes, against officials responsible for human rights violations in Hong Kong.

The protesters were delighted, carrying American flags and singing “The Star-Spangled Banner” in the streets of Hong Kong.

Beijing was enraged.

China has had sovereignty over Hong Kong since the British handed it over in 1997.

The Chinese government quickly banned U.S. military ships from docking in Hong Kong, a traditional port of call in the region.

The protesters, including many as young as Fiona, had changed the course of aircraft carriers and guided-missile destroyers.

Reporter Tom Lasseter exchanges Telegram messages with Lee.

The stakes for the kids of Hong Kong go well beyond a moment of geopolitical standoff.

When Britain passed the city to China, like a pearl slipping from the hand of one merchant to another, there was a written understanding that for 50 years Hong Kong would enjoy a great deal of autonomy. Known as “one country, two systems,” the agreement suspended some of the blow of a global finance center coming under the rule of the Chinese Communist Party.

The deal expires in 2047.

For Fiona, this means that in her lifetime she will live not in the freewheeling city to which she was born, but, quite possibly, in a place that’s just another dot on the map of China.

Chants at marches revolve around five protester demands, such as universal suffrage, with “Not one less!” the automatic refrain.

But conversations soon turn to a larger, more difficult topic at the root of their complaints.

China.

During interviews with more than a dozen protesters at Polytechnic and another university besieged at the same time, and continued contact with many of them in the weeks that followed, the subject sprang up repeatedly.

It’s never far, they said, the shadow of Beijing over the Hong Kong government’s policies.

“They’re all involved with this shit,” said Lee, who gave only her last name.

The 20-year-old nursing student covered her mouth after the obscenity, embarrassed to have said it out loud in the middle of a cafe, and quickly continued.

“Of course China is the big boss behind this.”

“If China is going to take over Hong Kong, we will lose our freedoms, we will lose our rights as humans,” she said.

Police had taken down her information when she surrendered outside Polytechnic University.

She didn’t yet know whether that would lead to an arrest on rioting charges, which could bring up to 10 years of prison.

“In my view, violence is the thing that protects us,” Lee said.

“It is a warning to those, like the police, who think they can do anything to us.”

The acceptance of violence isn’t limited to the barricades.

Joshua Wong, the global face of the movement’s lobbying efforts, said he understood the need for protesters “to defend themselves with force.”

As Wong spoke during an interview in Hong Kong on Wednesday, the headline on the front page of the South China Morning Post on the table next to his elbow read: “BOMB PLOTTERS ‘INTENDED TO TARGET POLICE AT MASS RALLY’”

If a group of protesters had indeed planned to bomb police, would that have been a step too far?

“I think the fundamental issue,” he said, “is we never can prove which strategy is the most effective or not-effective way to put pressure on Beijing.”

When Fiona first heard about a bill that would allow criminal suspects to be shipped from Hong Kong to mainland China, the initial trigger of the protests, she wasn’t concerned.

It was the sort of thing that troublemakers worried about.

“The extradition bill seemed good to me,” she said.

Her mother, a housewife from mainland China, is the product of a Communist education system that, as Fiona puts it, doesn’t “allow them to think about politics.”

She is still unaware, for example, that there was a massacre around Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in 1989.

Fiona’s father, from Hong Kong, drives a minibus taxi.

He has concerns about creeping mainland control, but his urge to “treasure our freedom” leaves him afraid of anything that might provoke Beijing’s wrath: “He keeps saying we should not do this and we should not do that.”

They live together in a sliver of a working-class district in Kowloon, the peninsula that juts above Hong Kong island.

It is a place of tiny apartments and people just trying to get by.

It was much better, everyone in her household agreed, to avoid politics.

On weekends, Fiona, who has a cartoon sticker of Cinderella on the back of her iPhone, usually went shopping with girlfriends from high school.

They looked for new outfits.

They chatted and had tea together.

But when Fiona saw the news that more than 3,000 Hong Kong lawyers dressed in black had marched against the proposed extradition bill on June 6, she wondered what was going on.

She clicked through YouTube on her cell phone.

She stopped on a Cantonese-language video uploaded about a week before by a young, handsome guy – hair cropped close on the sides and in a sort of thick flop on top – sitting on the edge of a bed. The video was speeded up so the presenter spoke in a fast blur, delivering on what he billed as, “Extradition bill 6 minute summary for dummies.”

The idea of the bill, on its face, wasn’t a problem, the young man said – public safety and rules are important.

The issue was that the judiciary in the mainland and the judiciary in Hong Kong are two totally different things.

The Chinese Communist Party, he said, might use this new linkage between the court systems to come after ordinary people who were exercising their freedom of speech, something protected in Hong Kong but not Beijing: “You may be extradited to China because of telling a joke.”

Fiona was alarmed.

People walk inside the Legislative Council building after protesters stormed the building on the anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover to China on July 1.

People walk inside the Legislative Council building after protesters stormed the building on the anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover to China on July 1.

Just a few days after her YouTube awakening, on June 9, she took the subway with a group of friends from high school over to Hong Kong island.

The crowd filled the march’s meeting point, Victoria Park, and soon flooded outside its boundaries. Between the glimmering towers of commerce, they yelled: “Fight for freedom! Stand with Hong Kong!”

They yelled: “No China extradition! No evil law!”

Fiona was astonished.

She couldn’t believe so many people had shown up.

The swell of the crowd, the boom and crash of its noise, was adrenaline and inspiration – “all of us were having the same aim,” Fiona said.

The city’s leader, Beijing-backed Carrie Lam, would have to relent, Fiona thought.

Faced with the will of so many citizens – a million came out that day, in a city of about 7.5 million – Lam had no choice but to meet with protesters and address their concerns.

That’s not what happened.

Three days later, the Hong Kong police shot rubber bullets and tear gas into a crowd.

On July 1, protesters wearing yellow construction hats and gauze masks stormed the city’s Legislative Council building on the 22nd anniversary of the handover from the British.

They smashed through glass doors with hammers, poles and road barriers, spray-painting the walls as the chaos churned – “HONG KONG IS NOT CHINA.”

On the night of November 16, as Fiona sat on the terrace at Polytechnic, a teenager slouched at his post on a pedestrian bridge on the other side of the school.

Reaching across a highway between the back of the university and a subway stop, the bridge could be a point of entry for police, the protesters feared.

The road underneath the bridge led to the Cross-Harbour Tunnel, a main artery linking Hong Kong island and the Kowloon Peninsula.

The protesters had blocked that route, hoping to trigger a citywide strike.

It was becoming clear that would not happen.

The teenager on the bridge, whose full name includes Pak and who sometimes goes by Paco, had the sleeves of his black Adidas windbreaker rolled up his arms.

His glasses jutted out of the eye-opening of his ski mask.

The 17-year-old, thick-set and volatile, recently had gotten kicked out of his house after arguing with his parents about the protests.

They’re both from mainland China, Pak explained.

“They always say, ‘Kill the protesters; the government is right.’”

There was a divide between him and his parents that couldn’t be crossed, he said.

As a student in Hong Kong, he received a relatively liberal education at school, complete with the underpinnings of Western philosophical and political thought.

Pak, second from right, spent shifts guarding the bridge during the standoff at Polytechnic.

Pak, second from right, spent shifts guarding the bridge during the standoff at Polytechnic.

A stockpile of arrows, bricks and umbrellas sits on a pedestrian bridge at Polytechnic University.

“I was born in Hong Kong. I know what is freedom. I know what is democracy. I know what is freedom of speech,” Pak said, his voice rising with each sentence.

His parents, on the other hand, were educated and raised on the mainland.

His shorthand for what that meant: “You know, we should love the Party, we should love Mao Zedong, blah, blah, blah.”

In his downtime, Pak hunched over an empty green Jolly Shandy Lemon bottle and poured lighter fluid inside.

He gestured to containers of cooking and peanut oil and said he added them as well because they helped the fire both burn and stick once the glass exploded.

He couldn’t count how many he’d filled in the past two days at Polytechnic.

Pak was working a shift as a lookout on the bridge.

He guzzled soda and coffee to stay awake, lifting his mask to slurp, revealing a round chin and an adolescent’s light dusting of hair on his upper lip.

There was a mattress on the floor around the corner for quick naps.

On a board leaning against the side of the walkway in front of him, a message was scrawled in capital letters: EYES OPEN!

Where did he think it was all headed?

Pak put the bottle down and said he saw nothing but struggle ahead.

“I think the violence of the protests will be increased; it will be upgraded,” he said.

“But we have no choice.”

When Pak was 12 years old, he watched news coverage of a massive, peaceful protest in Hong Kong, the 2014 “Umbrella Revolution,” a sit-in that called for universal suffrage.

The movement ended with protesters being hit by tear gas and hauled off to jail.

The nonviolent tactics, Pak said, got them nowhere.

Did he worry that the violence was taking place so near to a People’s Liberation Army barracks?

Not at all.

That morning, a separate barracks in Hong Kong was in the news when some of its soldiers, in exercise shorts and T-shirts, walked out to the road carrying red buckets and helped clean up debris left by protesters near the city’s Baptist University.

The event made both local and international headlines for the rarity of PLA soldiers’ appearance in public.

Under the city’s mini-constitution, the Chinese military can be called by the Hong Kong government to help maintain public order, but they “shall not interfere” in local affairs.

“I think they are testing us. If we attack the PLA, the PLA can shoot us and say, ‘OK, we were defending ourselves,’” Pak said.

“If we don’t attack the PLA, they will cross the line, again and again.”

But, he said, if the protesters continued ramping up violence against the cops, maybe the PLA would be called in.

And that, he said, would hand the protest movement victory.

“Other countries like [the] British and America can protect human rights in Hong Kong by sending troops to protect us,” he said.

It was, under any reading of the situation, a far-fetched idea.

Hong Kong is by international law the domain of China; the Chinese Communist Party can send in troops to clamp down on civil unrest.

There’s not been a hint of any Western power being interested in intervening on the ground.

Pak was right about one thing, though.

Police officers later massed on the other side of the bridge, piling out of their vehicles and walking in a long file to the head of the structure.

The protesters lit the bridge ablaze.

People screamed.

Flames leapt.

A funnel of black smoke filled the air.

The next night, Pak didn’t reply to notes sent by Telegram, the encrypted messaging app he used.

A day later, he still didn’t answer notes asking where he was.

The day after that, the same.

Pak was gone.

The young man lay his hands down on the table.

They were bandaged and his fingers curved over in an unnatural crook.

He’d not been out of his family’s house much in two weeks.

Tommy, 19, shredded his hands on a rope when he squeezed it hard as his body whooshed down off a bridge on the side of Polytechnic University.

They were better now, his fingers.

A photograph he sent just after, on November 20, showed a deep pocket of flesh ripped from his left pinkie, close to the bone by the look of it, and skin shredded across both hands.

“I didn’t wear gloves,” he explained.

After hitting the ground, he’d rushed to a line of waiting vehicles, driven by “parents” – protester slang for volunteers who show up to whisk them away from dangerous situations.

On the morning of November 18, while still inside Polytechnic, he had sent a note saying his actual parents knew he was there and he couldn’t find a way out.

Reporter Tom Lasseter exchanges messages on Telegram with Tommy during and after the standoff.

Reporter Tom Lasseter exchanges messages on Telegram with Tommy during and after the standoff.

“Worst case might be the police coming in polyu arresting all the people inside and beat them up,” he said in a note on Telegram, the chat platform.

“I’m like holy shit and i gotta be safe and not arrested.”

That evening, he was still there.

He didn’t see a way to escape.

Tommy went to the “front line” to face off with the police, not far from the ledge where Fiona sat a couple nights before.

Tommy carried a makeshift shield, a piece of wood and then part of a plastic road barrier, to protect himself from the blasts of a water cannon.

He didn’t make it very far.

Unlike most of the protesters who were around him, Tommy is a student at Polytechnic.

He has worked hard to get there.

He’s a kid from a far-flung village up toward the border with the mainland, where both of his parents are from.

Everyone in his village opposes the protests, he said, and there are “triads” in the area, members of organized-crime groups that are doing Beijing’s bidding.

Was he sorry that he’d put himself in danger?

“No regrets,” came the first text message response, at 7:29 p.m., even as police continued to mass outside Polytechnic and fears grew of a violent storming of the campus.

“They are wrong”

“We’re doing the right thing”

“It’s so unforgettable and good”

Hours later, he went down the rope.

Tommy, back to camera on the left, on the streets of Hong Kong a couple weeks after the standoff ended.

Tommy, back to camera on the left, on the streets of Hong Kong a couple weeks after the standoff ended.

Now, meeting to talk after a visit to a clinic for his hands, Tommy said he wasn’t sure what would come next for his city.

Or himself.

Although the university was still closed, he’d been keeping up with his studies, emailing professors and working on a paper about Hong Kong’s solid-waste treatment policy.

Unable to go to the gym because of the hand injury – his athletic frame sheathed in an Adidas jogging suit – Tommy had been feeling restless.

It was obvious the troubles would continue, he said.

“Carrie Lam will not accept the demands, the protesters will keep going, people will keep getting arrested,” he said.

“The government wants to arrest all the people.”

But the future would still arrive and he had his own dreams: of a wife and a family, and being a man who provided for them.

Tommy said he’d been thinking of applying for a government job after graduation.

They’re steady and have good benefits.

He would also remain a part of the protest movement.

How could he manage both?

Tommy paused a moment before answering.

Then, he said: “I have to become two people.”

On the afternoon of December 1, life was sunshine and breeze at the Hong Kong Cultural Centre. Inside, a youth orchestra was scheduled to play its annual concert, billed as “collaging Chinese music treasures from various soundscapes of China.”

Out front, facing the water, a band played cover songs – belting out the lyrics to Bon Jovi’s “You Give Love a Bad Name.”

Couples strolled on the boardwalk.

The palms swayed.

A shop sold ice cream.

And there was Pak, sitting on a bench.

He’d been arrested trying to flee Polytechnic in the early morning hours of November 19.

After a day spent in a police station, he made bail and moved back in with his parents.

Out in the open, in blue sweatpants and a grey sweatshirt, he was a pudgy teenager with the awkward habit of pushing his eyeglasses up the bridge of his nose as he spoke.

He had a couple pimples above his left eye.

Also, he was now facing a rioting charge, and had to report back to the police station in a few weeks.

Since his disappearance, the siege at Polytechnic had ended.

The protesters simmered down.

There was an election for local district councillors, and pro-democracy candidates won nearly 90% of 452 seats.

Victorious pro-democracy candidates in district council local elections gather outside the campus of Polytechnic University.

Victorious pro-democracy candidates in district council local elections gather outside the campus of Polytechnic University.

But two weeks after his arrest, Pak had shown up ready to protest again.

A march was slated to start in a couple hours.

He’d taken a bus down from one of Hong Kong’s poorest districts, with a black backpack that held his dark clothes and mask.

The lesson of the elections, he said, was that most Hong Kong citizens not only back the protests but “accept the violence level.”

Otherwise, he said, they would have rebuked the reform ticket and cast their lot with pro-government candidates.

“I think,” he said, “the violence of the protesters needs to upgrade to setting off bombs.”

He’d been reading about the Russian Revolution and Vladimir Lenin.

If he saw irony in studying the architect of the Soviet communist dictatorship while contemplating his own fight against the world’s preeminent Communist Party, he didn’t say so.

“The protesters, I think, will need some weapons, like rifles,” he said.

If it wasn’t possible to buy them, he said, it seemed easy enough to ransack police cars or even stations to steal them.

He described how that could be done.

The protests that day veered back to confrontation.

A black flag with the words “HONG KONG INDEPENDENCE” flapped above the crowd.

The scene to the north, in Kowloon, “descended into chaos as rioters hijacked public order events and resorted to destructive acts like building barricades on roads, setting fires and vandalising public facilities,” according to a police account.

Any hopes that the elections might bring peace seemed fragile.

December was off to a turbulent start.

In the weeks after walking out of Polytechnic University, slipping past the police, Fiona kept coming back to the heat of the protests.

An assembly to support those who protested at Polytechnic.

A rally to stop the use of tear gas, which featured little children carrying yellow balloons and a march past the city’s Legislative Council building.

And on a Saturday afternoon, the last day of November, a gathering of students and the elderly at the city’s Chater Garden.

The park sits among thick trappings of wealth and power – the private Hong Kong Club, rows of bank buildings and, just down the street, luxury laced across the store windows of Chanel and Cartier. Fiona was with a friend toward the back, on the top of a wall, out of sight of the TV cameras.

Her face was hidden behind a mask, as usual.

Even between protesters, they usually pass nicknames and nods, with nothing that identifies them in daily life.

Her friend, a boy who goes to the same high school, held forth on revolution and the perils of greater mainland China influence in Hong Kong.

Fiona listened, quietly.

She nodded her head.

She looked out at the crowd.

It felt good to see that she was not alone, Fiona said.

Though, she said, it was hard to tell where the movement was headed.

It could grind into the sort of underground movement that Tommy hinted at.

It could erupt in the boom of Pak’s bloody fantasy.

For Fiona, she knew there was always the danger that police might track down her earlier presence at Polytechnic, ending her precarious dance between homework and street unrest.

But sitting there, as the chants echoed and the sun began to slide down the sky over Hong Kong, Fiona said there was no choice but to keep fighting.

A week later, on Dec. 8, Fiona was at Victoria Park, almost six months to the day since her first protest started there.

Hundreds of thousands of people had come for the march.

It took Fiona an hour just to get out of the park as the throngs slowly squeezed onto the road outside.

When they saw messages on their cellphones that police had massed down one side street, Fiona and three friends threw on their respirator masks and goggles.

As they jogged in that direction, a stranger in the crowd handed them an umbrella; another stranger gave them bottles of water.

They joined a group of others, clutching umbrellas and advancing toward police lines, then coming to a halt.

No tear gas or rubber bullets came.

The police looked to have taken a step back.

Fiona and her friends dawdled, unsure of what to do.

They joined the march, a great mass of people churning through Hong Kong, at one point holding cell phones aloft, an ocean of bobbing lights.

They screamed obscenities at police when they saw them, with Fiona showing a middle finger and calling for their families to die.

They watched a man throw a hammer at the Bank of China building and heard the crash of breaking glass.

Someone pulled out a can of black spray paint.

In the middle of the road, Fiona and her friends took turns writing on the pavement.

They left a message: “If we burn, you burn with us!”

Fiona, on the left, watches as a friend paints graffiti across the road during the December 8 protest.

Fiona, on the left, watches as a friend paints graffiti across the road during the December 8 protest.

People walk inside the Legislative Council building after protesters stormed the building on the anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover to China on July 1.

People walk inside the Legislative Council building after protesters stormed the building on the anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover to China on July 1.  Pak, second from right, spent shifts guarding the bridge during the standoff at Polytechnic.

Pak, second from right, spent shifts guarding the bridge during the standoff at Polytechnic.

Reporter Tom Lasseter exchanges messages on Telegram with Tommy during and after the standoff.

Reporter Tom Lasseter exchanges messages on Telegram with Tommy during and after the standoff.  Tommy, back to camera on the left, on the streets of Hong Kong a couple weeks after the standoff ended.

Tommy, back to camera on the left, on the streets of Hong Kong a couple weeks after the standoff ended.  Victorious pro-democracy candidates in district council local elections gather outside the campus of Polytechnic University.

Victorious pro-democracy candidates in district council local elections gather outside the campus of Polytechnic University.  Fiona, on the left, watches as a friend paints graffiti across the road during the December 8 protest.

Fiona, on the left, watches as a friend paints graffiti across the road during the December 8 protest.