By Zachary Cohen and Alex Marquardt

Chinese "student" spies

"Student" spy Ji Chaoqun

Washington -- In August 2015, an electrical engineering student in Chicago sent an email to a Chinese national titled "Midterm test questions."

More than two years later, the email would turn up in an FBI probe in the Southern District of Ohio involving a Chinese intelligence officer who was trying to acquire technical information from a defense contractor.

Investigators took note.

They identified the email's writer as Ji Chaoqun, a Chinese student who would go on to enlist in the US Army Reserve.

More than two years later, the email would turn up in an FBI probe in the Southern District of Ohio involving a Chinese intelligence officer who was trying to acquire technical information from a defense contractor.

Investigators took note.

They identified the email's writer as Ji Chaoqun, a Chinese student who would go on to enlist in the US Army Reserve.

His email, they say, had nothing to do with exams.

Instead, at the direction of a high-level Chinese intelligence official, Ji attached background reports on eight US-based individuals who Beijing could target for potential recruitment as spies.

The eight -- naturalized US citizens originally from Taiwan or China -- had worked in science and technology.

Instead, at the direction of a high-level Chinese intelligence official, Ji attached background reports on eight US-based individuals who Beijing could target for potential recruitment as spies.

The eight -- naturalized US citizens originally from Taiwan or China -- had worked in science and technology.

Seven had worked for or recently retired from US defense contractors.

All of them were perceived as rich targets for a new form of espionage that China has been aggressively pursuing to win a silent war against the US for information and global influence.

Ji was arrested in September last year, accused of acting as an "illegal agent" at the direction of a "high-level intelligence officer" of a provincial department of the Ministry of State Security, China's top espionage agency, the Department of Justice said at the time.

He was formally indicted by a grand jury on January 24.

He was formally indicted by a grand jury on January 24.

Ji appeared in federal court in Chicago and pleaded not guilty, according to Joseph Fitzpatrick, a spokesman for the US attorney's office in Chicago.

While Ji has not been convicted, the circumstances outlined in his case demonstrate how China is using people from all walks of life with increasing frequency, current and former US intelligence officials tell CNN.

Beijing is leaning on expatriate Chinese scientists, businesspeople and students like Ji -- one of roughly 350,000 from China who study in the US every year -- to gain access to anything and everything at American universities and companies that's of interest to Beijing, according to current and former US intelligence officials, lawmakers and several experts.

The sheer size of the Chinese student population at US universities presents a major challenge for law enforcement and intelligence agencies tasked with striking the necessary balance between protecting America's open academic environment and mitigating the risk to national security.

While it remains unclear just how many of these students are on the radar of law enforcement, current and former intelligence officials told CNN that they all remain tethered to the Chinese espionage machine in some way.

It's part of a persistent, aggressive Chinese effort to undermine American industries, steal American secrets and eventually diminish American influence in the world so that Beijing can advance its own agenda, US officials, analysts and experts told CNN.

CIA Director Gina Haspel warned last year that China intends "to diminish US influence to advance their own goals."

China's approach to espionage is taking on added urgency as ties between Beijing and Washington sour over trade differences, cyberattacks and standoffs over military influence in Asia.

Beijing is leaning on expatriate Chinese scientists, businesspeople and students like Ji -- one of roughly 350,000 from China who study in the US every year -- to gain access to anything and everything at American universities and companies that's of interest to Beijing, according to current and former US intelligence officials, lawmakers and several experts.

The sheer size of the Chinese student population at US universities presents a major challenge for law enforcement and intelligence agencies tasked with striking the necessary balance between protecting America's open academic environment and mitigating the risk to national security.

While it remains unclear just how many of these students are on the radar of law enforcement, current and former intelligence officials told CNN that they all remain tethered to the Chinese espionage machine in some way.

It's part of a persistent, aggressive Chinese effort to undermine American industries, steal American secrets and eventually diminish American influence in the world so that Beijing can advance its own agenda, US officials, analysts and experts told CNN.

CIA Director Gina Haspel warned last year that China intends "to diminish US influence to advance their own goals."

China's approach to espionage is taking on added urgency as ties between Beijing and Washington sour over trade differences, cyberattacks and standoffs over military influence in Asia.

"China's intelligence services exploit the openness of American society, especially academia and the scientific community, using a variety of means," according to the intelligence community's World Wide Threat Assessment.

Lawmakers are also sounding the alarm.

"There is no comparison to the breadth and scope of the Chinese threat facing America today, as they actively seek to supplant the US globally," Republican Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida told CNN, noting that Russia and China have taken similar approaches when it comes to nontraditional espionage.

'Covert influencers'

For more than a decade, US law enforcement and intelligence officials have raised internal concerns about US universities becoming soft targets for Chinese intelligence services that use Chinese students and staff to access emerging technologies, according to multiple former US officials.

But in recent months, senior officials have expressed a renewed sense of urgency in addressing the issue and sought to increase public awareness by highlighting the threat during congressional testimony and while speaking at various security forums.

While US officials stress that they believe some Chinese students are here for legitimate purposes, they have also made it clear that the Trump administration continues to grapple with counterintelligence concerns posed by Chinese agents seeking to exploit vulnerabilities within academic institutions.

Rather than having trained spies attempt to infiltrate US universities and businesses, Chinese intelligence services have strategically utilized members of its student population to act as "access agents" or "covert influencers," according to Joe Augustyn, a former CIA officer with firsthand knowledge of the issue from his time at the agency.

Creating this degree of separation allows the Chinese government to maintain some deniability should an operation become exposed, Augustyn said.

"We allow 350,000 or so Chinese students here every year," William Evanina, director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, said last April during an Aspen Institute conference.

"There is no comparison to the breadth and scope of the Chinese threat facing America today, as they actively seek to supplant the US globally," Republican Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida told CNN, noting that Russia and China have taken similar approaches when it comes to nontraditional espionage.

'Covert influencers'

For more than a decade, US law enforcement and intelligence officials have raised internal concerns about US universities becoming soft targets for Chinese intelligence services that use Chinese students and staff to access emerging technologies, according to multiple former US officials.

But in recent months, senior officials have expressed a renewed sense of urgency in addressing the issue and sought to increase public awareness by highlighting the threat during congressional testimony and while speaking at various security forums.

While US officials stress that they believe some Chinese students are here for legitimate purposes, they have also made it clear that the Trump administration continues to grapple with counterintelligence concerns posed by Chinese agents seeking to exploit vulnerabilities within academic institutions.

Rather than having trained spies attempt to infiltrate US universities and businesses, Chinese intelligence services have strategically utilized members of its student population to act as "access agents" or "covert influencers," according to Joe Augustyn, a former CIA officer with firsthand knowledge of the issue from his time at the agency.

Creating this degree of separation allows the Chinese government to maintain some deniability should an operation become exposed, Augustyn said.

"We allow 350,000 or so Chinese students here every year," William Evanina, director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, said last April during an Aspen Institute conference.

"That's too much. We have a very liberal visa policy for them. It is a tool that is used by the Chinese government to facilitate nefarious activity here in the US."

Chinese students now constitute the largest foreign student body in the US, according to data from the Institute of International Education.

US intelligence officials have taken note of the steady increase in Chinese students entering the country each year and are well aware of the challenges associated with that trend.

Along with cyber-intrusion and strategic investing in American businesses, senior US intelligence officials told CNN on Tuesday that China is tapping into its massive network of Chinese students to compress the time it takes to acquire certain capabilities.

Chinese students now constitute the largest foreign student body in the US, according to data from the Institute of International Education.

US intelligence officials have taken note of the steady increase in Chinese students entering the country each year and are well aware of the challenges associated with that trend.

Along with cyber-intrusion and strategic investing in American businesses, senior US intelligence officials told CNN on Tuesday that China is tapping into its massive network of Chinese students to compress the time it takes to acquire certain capabilities.

"In a world where technology is available, where we are training their scientists and engineers, and their scientists and engineers were already good on their own, we are just making them able to not have to toil for the same amount of time to get capabilities that will rival or test us," a senior official in the office of Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats said.

Addressing that problem is difficult given the large population of Chinese student spies sent to the US each year.

"We know without a doubt that anytime a graduate student from China comes to the US, they are briefed when they go, and briefed when they come back," according to Augustyn.

"We know without a doubt that anytime a graduate student from China comes to the US, they are briefed when they go, and briefed when they come back," according to Augustyn.

"There is no question in my mind, depending on where they are and what they are doing, that they have a role to play for their government."

In Ji's case, he was first approached by a Chinese intelligence officer who, initially at least, used a false identity, according to FBI Special Agent Andrew McKay, who filed a criminal complaint against Ji in the US District Court in Chicago.

The complaint charges Ji with one count of knowingly acting in the US as an agent of Chinese government without prior notification to the attorney general.

The complaint charges Ji with one count of knowingly acting in the US as an agent of Chinese government without prior notification to the attorney general.

Ji has been detained since his arrest in September, according to his lawyer.

Like thousands of Chinese nationals who come to the US each year, Ji entered the country on an F1 visa -- used for international students in academic programs.

Citing immigration records, the complaint states that Ji's goal, when he landed in Chicago in August 2013, was to study electrical engineering at the Illinois Institute of Technology, where he ultimately earned a master's degree.

By December, Ji had been approached by the high-level Chinese intelligence official, who presented himself as a professor at Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

Ji, now 27, eventually realized who this official and his colleagues really were, according to the criminal complaint.

Still, court documents say he would funnel them background reports on other Chinese civilians living in the US who might be pressured to serve as spies -- in this case, in the strategically critical US industries of aerospace and technology.

Like thousands of Chinese nationals who come to the US each year, Ji entered the country on an F1 visa -- used for international students in academic programs.

Citing immigration records, the complaint states that Ji's goal, when he landed in Chicago in August 2013, was to study electrical engineering at the Illinois Institute of Technology, where he ultimately earned a master's degree.

By December, Ji had been approached by the high-level Chinese intelligence official, who presented himself as a professor at Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

Ji, now 27, eventually realized who this official and his colleagues really were, according to the criminal complaint.

Still, court documents say he would funnel them background reports on other Chinese civilians living in the US who might be pressured to serve as spies -- in this case, in the strategically critical US industries of aerospace and technology.

And he would lie to US officials about it, according to the complaint filed by FBI investigators.

In their response, the Chinese government did not comment on the current status of Ji's case.

But in September, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang told CNN he was "unaware of the situation" when asked about Ji's arrest during a press briefing.

According to the complaint, FBI agents discovered about 36 text messages on one iCloud account that Ji and the intelligence officer exchanged between December 2013 and July 2015.

In their response, the Chinese government did not comment on the current status of Ji's case.

But in September, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Geng Shuang told CNN he was "unaware of the situation" when asked about Ji's arrest during a press briefing.

According to the complaint, FBI agents discovered about 36 text messages on one iCloud account that Ji and the intelligence officer exchanged between December 2013 and July 2015.

In 2016, after he graduated, Ji enlisted in the US Army Reserve under a program in which foreign nationals can be recruited if their skills are considered "vital to the national interest."

As part of his Army interview and in his security clearance application, Ji was asked if he'd had contact with foreign security services, the complaint says.

He answered "no."

The Washington Post previously reported that Ji's case has been linked to the indictment of a Chinese intelligence officer named Xu Yanjun.

Xu's indictment was unsealed in October after he was arrested in Belgium for stealing trade secrets from US aerospace companies.

As part of his Army interview and in his security clearance application, Ji was asked if he'd had contact with foreign security services, the complaint says.

He answered "no."

The Washington Post previously reported that Ji's case has been linked to the indictment of a Chinese intelligence officer named Xu Yanjun.

Xu's indictment was unsealed in October after he was arrested in Belgium for stealing trade secrets from US aerospace companies.

He is the first Chinese intelligence officer to be extradited for prosecution in the US.

He has pleaded not guilty.

Complex counter intelligence challenge

FBI Director Christopher Wray, in the past year, has sought to focus repeatedly on the threat from Chinese students in US universities trying to get access to sensitive military and civilian research.

"They're exploiting the very open research and development environment that we have," Wray told a Senate Intelligence Committee hearing last year, expressing concern that academic officials aren't taking the threat from China seriously enough.

But Wray told Senate lawmakers he has seen reasons for optimism.

"One of the things that I've been most encouraged about in an otherwise bleak landscape is the degree to which -- as Director Coats was alluding to -- American companies are waking up, American universities are waking up, our foreign partners are waking up," Wray said.

Complex counter intelligence challenge

FBI Director Christopher Wray, in the past year, has sought to focus repeatedly on the threat from Chinese students in US universities trying to get access to sensitive military and civilian research.

"They're exploiting the very open research and development environment that we have," Wray told a Senate Intelligence Committee hearing last year, expressing concern that academic officials aren't taking the threat from China seriously enough.

But Wray told Senate lawmakers he has seen reasons for optimism.

"One of the things that I've been most encouraged about in an otherwise bleak landscape is the degree to which -- as Director Coats was alluding to -- American companies are waking up, American universities are waking up, our foreign partners are waking up," Wray said.

Still, the issue continues to pose a complex counterintelligence challenge for the US.

The Chinese are notorious for appealing to the nationalism and loyalty of their citizens to coerce them into carrying out acts of espionage, lawmakers and intelligence officials say.

Sen. Mark Warner of Virginia, the leading Democrat on the Senate's Select Committee on Intelligence, stressed that it is important to recognize "that the Chinese government has enormous power over its citizens."

"In China, only the government can grant someone permission to leave the country to study or work in the United States and we have seen the Chinese government use their power over their citizens to encourage those citizens to commit acts of scientific or industrial espionage to the benefit of the Chinese government," he told CNN.

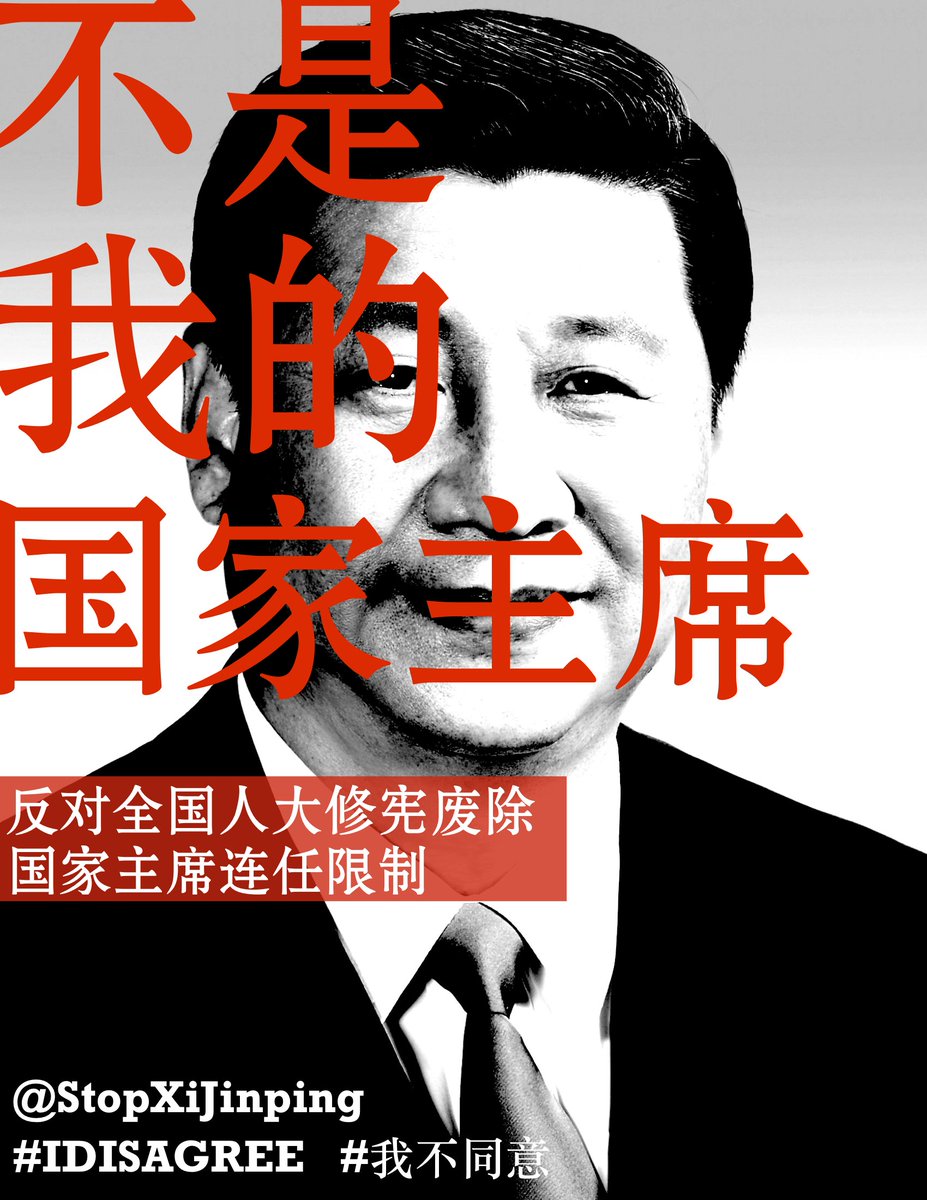

The ruling Communist Party in China has tightened its grip over all aspects of Chinese society, including academia, under Xi Jinping, who has routinely said that "the Party exercises overall leadership over all areas of endeavor in every part of the country."

Sen. Mark Warner of Virginia, the leading Democrat on the Senate's Select Committee on Intelligence, stressed that it is important to recognize "that the Chinese government has enormous power over its citizens."

"In China, only the government can grant someone permission to leave the country to study or work in the United States and we have seen the Chinese government use their power over their citizens to encourage those citizens to commit acts of scientific or industrial espionage to the benefit of the Chinese government," he told CNN.

The ruling Communist Party in China has tightened its grip over all aspects of Chinese society, including academia, under Xi Jinping, who has routinely said that "the Party exercises overall leadership over all areas of endeavor in every part of the country."

The State Department has considered implementing stricter vetting measures for F1 Visa applicants like Ji in an effort to address the problem, administration officials have told CNN, though the details of that plan remain unclear.

The Trump administration has also insisted that any trade deal with China must address concerns about Beijing's use of covert operations to steal US government secrets and intellectual property belonging to American private-sector businesses.

Ahead of President Donald Trump's December dinner meeting with Xi in Buenos Aires, the top US trade negotiator released a 50-page report showing Beijing had done little to fix unfair policies and that it continued to conduct and support cyber-enabled economic espionage that has stolen trillions of dollars in intellectual property.

The Trump administration has said the huge waves of tariffs it has slapped on Chinese goods are part of an effort to stop Beijing from unfairly getting its hands on American technology.

The Trump administration has also insisted that any trade deal with China must address concerns about Beijing's use of covert operations to steal US government secrets and intellectual property belonging to American private-sector businesses.

Ahead of President Donald Trump's December dinner meeting with Xi in Buenos Aires, the top US trade negotiator released a 50-page report showing Beijing had done little to fix unfair policies and that it continued to conduct and support cyber-enabled economic espionage that has stolen trillions of dollars in intellectual property.

The Trump administration has said the huge waves of tariffs it has slapped on Chinese goods are part of an effort to stop Beijing from unfairly getting its hands on American technology.

Prior to releasing the National Intelligence Strategy, The Office of the Director of National Intelligence issued new warnings and information to technology and aviation companies believed to be targets to help the private sector guard against growing threats from Chinese intelligence entities.

A US intelligence official told CNN that American companies need to be alert to the growing threat. "Whether it is a Chinese national, student, businessman or through cyber means, companies need to know they are up against China who wants their information," the official said.

US authorities are also taking action beyond just issuing warnings.

Since August 2017, the Justice Department has indicted several individuals and corporations on charges related to economic espionage and intellectual property theft, predominantly in the aerospace and high-technology sectors.

One October 2018 indictment accused two Chinese intelligence officers of attempting to hack and infiltrate private companies over the course of five years in an attempt to steal technology.

The indictment also targeted six of what it said were the officers' paid hackers and two Chinese nationals, employed by a French aerospace company, who were told by the officers to obtain information about a turbofan engine developed in partnership with a US-based plane maker.

A US intelligence official told CNN that American companies need to be alert to the growing threat. "Whether it is a Chinese national, student, businessman or through cyber means, companies need to know they are up against China who wants their information," the official said.

US authorities are also taking action beyond just issuing warnings.

Since August 2017, the Justice Department has indicted several individuals and corporations on charges related to economic espionage and intellectual property theft, predominantly in the aerospace and high-technology sectors.

One October 2018 indictment accused two Chinese intelligence officers of attempting to hack and infiltrate private companies over the course of five years in an attempt to steal technology.

The indictment also targeted six of what it said were the officers' paid hackers and two Chinese nationals, employed by a French aerospace company, who were told by the officers to obtain information about a turbofan engine developed in partnership with a US-based plane maker.

And prior to that, in September, US authorities arrested Ji for allegedly spying on behalf of Beijing.

McKay and the FBI used search warrants to scour emails and texts that were used to piece together what they claim is the story of how Ji was lured in and exploited by his Chinese spymasters.

They sent an undercover agent who pretended he'd been directed by Chinese intelligence to meet Ji after one of the student's alleged handlers had been arrested.

Video and audio recordings captured Ji telling the undercover FBI officer he knew he'd been helping a "confidential unit" of the government -- exactly the actions he'd denied in his interviews for both a student visa and his entry to the US Army Reserve program, according to the complaint.

"Ji specifically denied having had contact with Chinese government within the past seven years," the Department of Justice said in a press release, citing the complaint.

McKay and the FBI used search warrants to scour emails and texts that were used to piece together what they claim is the story of how Ji was lured in and exploited by his Chinese spymasters.

They sent an undercover agent who pretended he'd been directed by Chinese intelligence to meet Ji after one of the student's alleged handlers had been arrested.

Video and audio recordings captured Ji telling the undercover FBI officer he knew he'd been helping a "confidential unit" of the government -- exactly the actions he'd denied in his interviews for both a student visa and his entry to the US Army Reserve program, according to the complaint.

"Ji specifically denied having had contact with Chinese government within the past seven years," the Department of Justice said in a press release, citing the complaint.

Still, US officials say addressing the issue requires striking a delicate balance and more than just outreach.

"Despite active engagement with academia, industry, and the greater public on this issue, however, Chinese efforts to exploit America's accessible academic environment continue to grow," E.W. Priestap, assistant director of the FBI's counterintelligence division, told lawmakers last year.

"Despite active engagement with academia, industry, and the greater public on this issue, however, Chinese efforts to exploit America's accessible academic environment continue to grow," E.W. Priestap, assistant director of the FBI's counterintelligence division, told lawmakers last year.

"In particular, as internet access, cyber exploitation, transnational travel, and payment technologies proliferate, so, too, do Chinese options for exploiting America's schools for domestic gain."

US Vice-President Mike Pence name-checked strategist Michael Pillsbury twice during a speech at the Hudson Institute in Washington on October 4.

US Vice-President Mike Pence name-checked strategist Michael Pillsbury twice during a speech at the Hudson Institute in Washington on October 4.