One mainlander’s story of resistance and risk.

BY QIU ZHONGSUN

I took one final look at the posters I had just taped to the bulletin board in a student lounge at the University of California, San Diego.

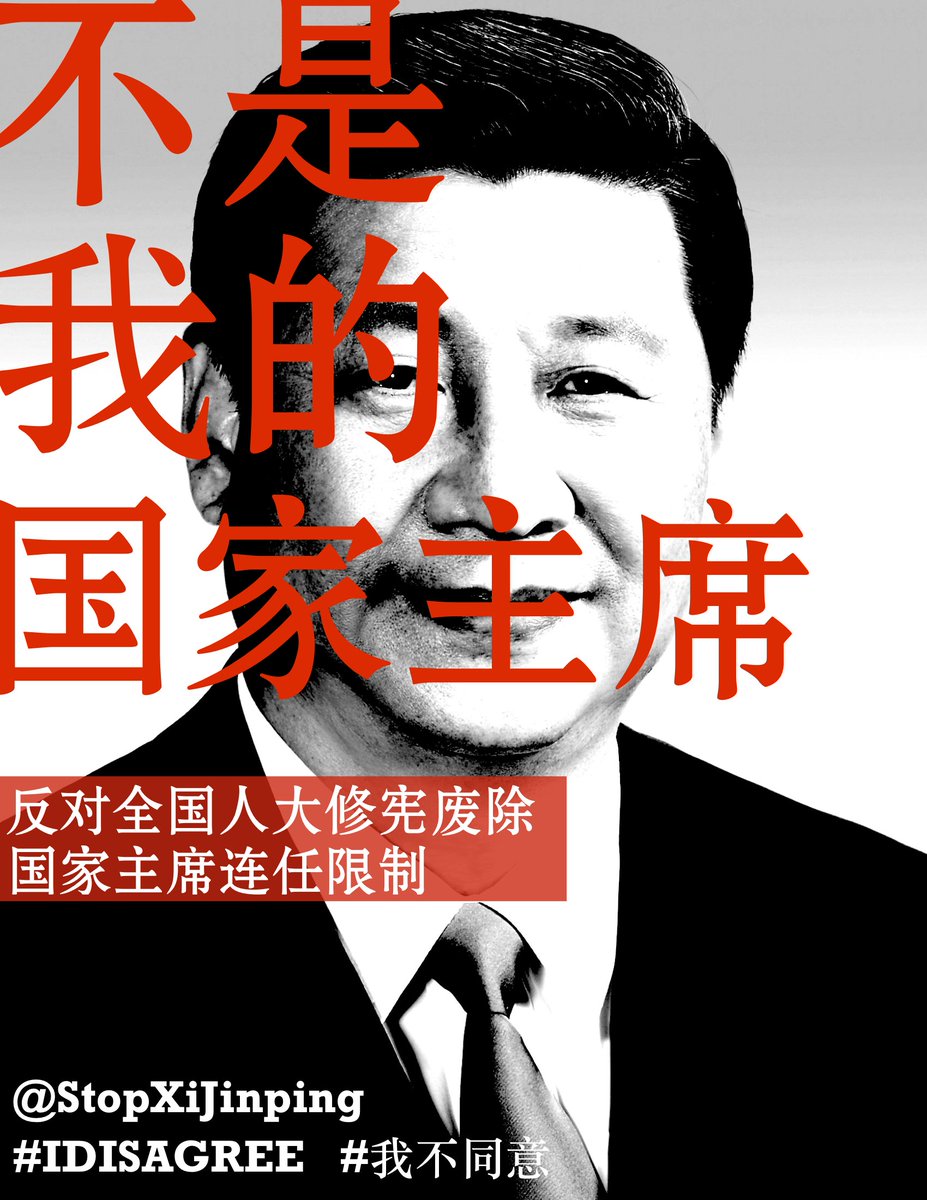

Superimposed over the face of Xi Jinping were three simple words in red: Not My President.

My own face had been concealed under a hoodie as I put the pictures up — and I’d waited, along with a friend, until late at night to make sure no one saw us.

I had to take these measures to protect my identity because for mainland Chinese like myself, the oppression we face at home follows us abroad.

I had to take these measures to protect my identity because for mainland Chinese like myself, the oppression we face at home follows us abroad.

The Chinese Communist Party has learned how to project its regime of surveillance and coercion deep inside the borders of liberal democracies.

Initiating a campaign of political resistance, even in a Western country, meant risking my safety and that of my family back in China.

Just a few days earlier, on Feb. 25, the National People’s Congress, China’s rubber-stamp legislative body, had announced a proposal to remove constitutional term limits on the presidency, which since the 1980s had been limited to two five-year terms.

Just a few days earlier, on Feb. 25, the National People’s Congress, China’s rubber-stamp legislative body, had announced a proposal to remove constitutional term limits on the presidency, which since the 1980s had been limited to two five-year terms.

Chinese presidents aren’t elected, but the selection process, ever since reformer Deng Xiaoping, had been a matter of consensus among the top echelons of the party, deliberately limiting the strength of any one individual.

After the proposal inevitably passed, it would smooth the course for Xi, chosen for the critical roles of both party chairman and president in 2012, to become president for life instead of quitting in 2022.

News of the proposal swept China’s social media, and posts expressing frustration, shock, and helplessness flooded online platforms — but only for a few short hours.

News of the proposal swept China’s social media, and posts expressing frustration, shock, and helplessness flooded online platforms — but only for a few short hours.

Then, all the discussion was deleted as the myriad censors who now police the Chinese internet kicked into high gear.

That was when I and two of my friends finally decided to act.

That was when I and two of my friends finally decided to act.

As mainland Chinese studying and living in Western countries, we’ve been watching with dismay from afar as Xi has cracked down on human rights activists, nullified Hong Kong’s democratic promises, and revived a personality cult that reminds some Chinese of what China experienced under former leader Mao Zedong.

Xi’s power grab was the last straw.

We were raised to embrace the Communist Party, but now we felt it was time for those of us who live overseas to speak up for those silenced at home.

So we decided to start a Twitter campaign called #NotMyPresident and encourage like-minded Chinese students at universities around the world to print out our posters and put them up on their campuses.

So we decided to start a Twitter campaign called #NotMyPresident and encourage like-minded Chinese students at universities around the world to print out our posters and put them up on their campuses.

Within a month, Chinese students at more than 30 schools around the world had joined us, including at Cornell University, London School of Economics, University of Sydney, and the University of Hong Kong, expressing their disapproval for a Chinese president for life.

After Foreign Policy’s initial coverage, Western media outlets such as the New York Times and the BBC featured our campaign.

But we had to be extremely cautious in making our voices heard.

But we had to be extremely cautious in making our voices heard.

Putting up posters is a common political activity on college campuses in democratic countries.

But for Chinese studying at these same campuses, it is dangerous to publicly express opinions that go against the party line.

We know that our career prospects back in China are likely to suffer if we are publicly known to have criticized the party; it will be more difficult for us to make connections, snag interviews, and receive job offers and promotions.

Chinese authorities have also been known to harass the families of outspoken Chinese students abroad, to interrogate Chinese returnees, or, in extreme cases, even kidnap Chinese abroad

Cand force them back to China.

So we planned carefully and took steps to protect our identities.

Cand force them back to China.

So we planned carefully and took steps to protect our identities.

The first challenge was to set up secure communication among the organizers.

We avoided discussing anything regarding the campaign on WeChat, the most popular instant messaging application in the Chinese-speaking world, because it is rigorously monitored by the Chinese government.

That means that Chinese security officials may read WeChat messages sent between people who aren’t even in China.

But even with encrypted messaging applications backed by Facebook and other Western technology companies, we still used burner phones to sign up as we were afraid that eventually companies behind the service would hand over the control of the user data to Chinese authorities — just as Apple did in February, when it agreed to house all Chinese users’ data locally.

The consequences if our identities got out could be dire.

But even with encrypted messaging applications backed by Facebook and other Western technology companies, we still used burner phones to sign up as we were afraid that eventually companies behind the service would hand over the control of the user data to Chinese authorities — just as Apple did in February, when it agreed to house all Chinese users’ data locally.

The consequences if our identities got out could be dire.

Organizing a campaign that questions the fundamental legitimacy of China’s top leader is a punishable crime in China.

Citing the designated charge of “inciting subversion of state power,” Chinese authorities can arrest and prosecute citizens who dare to disagree without due process — and that would include us, although the protest took place thousands of miles away from home.

As we publicized the campaign, we encouraged potential participants to put up the posters under cover of darkness and to wear masks in order to protect their own identities as well.

As we publicized the campaign, we encouraged potential participants to put up the posters under cover of darkness and to wear masks in order to protect their own identities as well.

We have learned from previous incidents that the Chinese community abroad is unlikely to support dissident speech — and that Chinese student groups effectively serve as watchdogs for the "motherland" on foreign campuses.

Many Chinese students remember the Shuping Yang incident in May 2017.

An undergraduate student at the University of Maryland, Yang criticized environmental problems in China and praised democratic values during her commencement speech.

Her speech was recorded, put online, and went viral in China.

Chinese state media labeled her speech as “anti-China,” and angry netizens dug up her parents’ address and posted it online.

Throughout the incident, the Chinese Students and Scholars Association (CSSA) at the university did not provide any support to Yang.

Rather, the CSSA denounced her speech as “intolerable” and questioned her real motives.

Yang eventually posted an apology on Chinese social media.

In 2008, a Duke University student named Grace Wang attempted to mediate between pro-Tibet and pro-Beijing student protesters and was subsequently attacked on the Chinese-language internet; she received violent threats, and her parents back in China went into hiding.

As more and more schools joined the campaign, our Twitter account started to garner attention — both wanted and unwanted.

As more and more schools joined the campaign, our Twitter account started to garner attention — both wanted and unwanted.

On the one hand, we tried to discourage students in mainland China from participating.

With the help of deep learning and artificial intelligence, the government has put into place sweeping public surveillance technology.

We also faced a barrage of phishing attempts.

We also faced a barrage of phishing attempts.

Every day, we received dubious password reset requests in the inboxes of each campaign-related account: Twitter, Facebook, Gmail, even the Dropbox account we used to host our posters for download.

Some of these were from unknown parties, claiming that our Twitter account was blocked and inviting us to click on the “unlock” button.

Other, more subtle attempts would appear as emails from potential campaign participants — but instead of sending a picture of the posters they put up on campus, as we requested from all our participants, a suspicious link was included.

Despite the risks that every participant faced, the support we received greatly exceeded our expectation.

Despite the risks that every participant faced, the support we received greatly exceeded our expectation.

One participant at the University of California, Irvine sent a moving message: “I struggled for a while about whether to put those posters up because I was worried that I might get caught by someone who disagrees with my action. Yet, Martin Luther King Jr. once said, ‘Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.’ So I decided to take the risks because what Xi did is absolutely wrong, and people are being silent for too long. I hope this can make a difference and pray that things will get better.”

When we put up posters at UC San Diego on that cold early spring night, we hoped it would be a small rebellion, a personal farewell to the ideology of party supremacy we were raised to believe.

When we put up posters at UC San Diego on that cold early spring night, we hoped it would be a small rebellion, a personal farewell to the ideology of party supremacy we were raised to believe.

It turns out we are not alone.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire