By MARK LANDLER and DAVID E. SANGER

President Donald J. Trump at the Carrier plant in Indianapolis on Thursday.

WASHINGTON — President-elect Donald J. Trump spoke by telephone with Taiwan’s president on Friday, a striking break with nearly four decades of diplomatic practice that could precipitate a major rift with China even before Mr. Trump takes office.

Mr. Trump’s office said he had spoken with the Taiwanese president, Tsai Ing-wen, “who offered her congratulations.”

President Tsai Ing-wen

The longer-term fallout from the Trump-Tsai conversation could be significant, the administration official said, noting that the Chinese government issued a bitter protest after the United States sold weapons to Taiwan as part of a well-established arms agreement grudgingly accepted by Beijing.

Mr. Trump’s call with President Tsai is a bigger provocation.

President Donald J. Trump at the Carrier plant in Indianapolis on Thursday.

WASHINGTON — President-elect Donald J. Trump spoke by telephone with Taiwan’s president on Friday, a striking break with nearly four decades of diplomatic practice that could precipitate a major rift with China even before Mr. Trump takes office.

Mr. Trump’s office said he had spoken with the Taiwanese president, Tsai Ing-wen, “who offered her congratulations.”

He is the first president who has spoken to a Taiwanese leader since 1979, when the United States severed diplomatic ties with Taiwan as part of its recognition of the People’s Republic of China.

In the statement, Mr. Trump’s office said the two leaders had noted “the close economic, political, and security ties” between Taiwan and the United States.

In the statement, Mr. Trump’s office said the two leaders had noted “the close economic, political, and security ties” between Taiwan and the United States.

Mr. Trump, it said, “also congratulated President Tsai on becoming President of Taiwan earlier this year.”

Mr. Trump’s motives in taking the call, which lasted more than 10 minutes, were not clear.

Mr. Trump’s motives in taking the call, which lasted more than 10 minutes, were not clear.

In a Twitter message late Friday, he said Ms. Tsai “CALLED ME.”

But diplomats with ties to Taiwan said it was highly unlikely that the Taiwanese leader would have made the call without arranging it in advance.

But diplomats with ties to Taiwan said it was highly unlikely that the Taiwanese leader would have made the call without arranging it in advance.

Ms. Tsai’s office confirmed that it had taken place, saying the two had discussed promoting economic development and “strengthening defense.”

Taiwan’s Central News Agency hailed the call as “historic.”

The president has shown little heed for the nuances of international diplomacy, holding a series of unscripted phone calls to foreign leaders that have roiled sensitive relationships with Britain, India and Pakistan.

The president has shown little heed for the nuances of international diplomacy, holding a series of unscripted phone calls to foreign leaders that have roiled sensitive relationships with Britain, India and Pakistan.

On Thursday, the White House urged Mr. Trump to use experts from the State Department to prepare him for these exchanges.

The White House was not told about Mr. Trump’s call until after it happened, according to a senior administration official.

The White House was not told about Mr. Trump’s call until after it happened, according to a senior administration official.

But afterward, the Chinese government contacted the White House to discuss the matter.

President Tsai Ing-wen

The longer-term fallout from the Trump-Tsai conversation could be significant, the administration official said, noting that the Chinese government issued a bitter protest after the United States sold weapons to Taiwan as part of a well-established arms agreement grudgingly accepted by Beijing.

Mr. Trump’s call with President Tsai is a bigger provocation.

Beijing views Taiwan as a breakaway province and has adamantly opposed the attempts of any country to carry on official relations with it.

On Nov. 14, Mr. Trump spoke with Xi Jinping and a statement from the transition team said the two men had a “clear sense of mutual respect.”

Initial reaction from China about Friday’s telephone call was surprise verging on disbelief.

On Nov. 14, Mr. Trump spoke with Xi Jinping and a statement from the transition team said the two men had a “clear sense of mutual respect.”

Initial reaction from China about Friday’s telephone call was surprise verging on disbelief.

“This is a big event, the first challenge the president has made to China,” said Shi Yinhong, professor of international relations at Renmin University in Beijing.

“This must be bad news for the Chinese leadership.”

Official state-run media have portrayed Mr. Trump in a positive light, casting him as a businessman China could get along with.

Official state-run media have portrayed Mr. Trump in a positive light, casting him as a businessman China could get along with.

He was favored among Chinese commentators during the election over Hillary Clinton, who was perceived as being too hard on China.

Mr. Trump’s exchange touched “the most sensitive spot” for China’s foreign policy, Mr. Shi said.

Mr. Trump’s exchange touched “the most sensitive spot” for China’s foreign policy, Mr. Shi said.

The government, he said, would most likely interpret it as encouraging Ms. Tsai, the leader of the party that favors independence from the mainland, to continue to resist pressure from Beijing.

Among diplomats in the United States, there was similar shock.

Among diplomats in the United States, there was similar shock.

“This is a change of historic proportions,” said Evan S. Medeiros, a former senior director of Asian affairs in the Obama administration.

In a second Twitter message about the call Friday night, Mr. Trump said, “Interesting how the U.S. sells Taiwan billions of dollars of military equipment but I should not accept a congratulatory call.”

Ties between the United States and Taiwan are currently managed through quasi-official institutions. The American Institute in Taiwan issues visas and provides other basic consular services, and Taiwan has an equivalent institution with offices in several cities in the United States.

These arrangements are the outgrowth of the One China policy that has governed relations between the United States and China since President Richard M. Nixon’s historic meeting with Mao Zedong in Beijing in 1972.

Ties between the United States and Taiwan are currently managed through quasi-official institutions. The American Institute in Taiwan issues visas and provides other basic consular services, and Taiwan has an equivalent institution with offices in several cities in the United States.

These arrangements are the outgrowth of the One China policy that has governed relations between the United States and China since President Richard M. Nixon’s historic meeting with Mao Zedong in Beijing in 1972.

In 1978, President Jimmy Carter formally recognized Beijing as the sole government of China, abrogating its ties with Taipei a year later.

The call also raised questions of conflicts of interest.

Newspapers in Taiwan reported last month that a Trump Organization representative had visited the country, expressing interest in perhaps developing a hotel project adjacent to Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport, which is undergoing a major expansion.

The call also raised questions of conflicts of interest.

Newspapers in Taiwan reported last month that a Trump Organization representative had visited the country, expressing interest in perhaps developing a hotel project adjacent to Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport, which is undergoing a major expansion.

The mayor of Taoyuan, Cheng Wen-tsan, was quoted as confirming that visit.

A spokeswoman for the Trump Organization, Amanda Miller, said that the company had “no plans for expansion into Taiwan,” and that there had been no “authorized visits” to the country to push a Trump development project.

A spokeswoman for the Trump Organization, Amanda Miller, said that the company had “no plans for expansion into Taiwan,” and that there had been no “authorized visits” to the country to push a Trump development project.

But Ms. Miller did not dispute that Anne-Marie Donoghue, a sales manager overseeing Asia for Trump Hotels, had visited Taiwan in October, a trip that Ms. Donoghue recorded on her Facebook page.

Ms. Donoghue did not respond to requests for comment.

Mr. Trump’s call with the Taiwanese president came just as Obama delivered a more subtle, but also aggressive, rebuff of China: He blocked, by executive order, an effort by Chinese investors to buy a semiconductor production firm called Aixtron.

Mr. Obama took the action on national security grounds, after an intelligence review concluded that the technology could be used for “military applications” and help provide an “overall technical body of knowledge and experience” to the Chinese.

The decision is likely to accelerate tension with Beijing, as Chinese authorities make it extraordinarily difficult for American technology companies, including Google and Facebook, to gain access to the Chinese market, and Washington seeks to slow China’s acquisition of critical technology.

Mr. Trump has made little effort to avoid antagonizing China.

Ms. Donoghue did not respond to requests for comment.

Mr. Trump’s call with the Taiwanese president came just as Obama delivered a more subtle, but also aggressive, rebuff of China: He blocked, by executive order, an effort by Chinese investors to buy a semiconductor production firm called Aixtron.

Mr. Obama took the action on national security grounds, after an intelligence review concluded that the technology could be used for “military applications” and help provide an “overall technical body of knowledge and experience” to the Chinese.

The decision is likely to accelerate tension with Beijing, as Chinese authorities make it extraordinarily difficult for American technology companies, including Google and Facebook, to gain access to the Chinese market, and Washington seeks to slow China’s acquisition of critical technology.

Mr. Trump has made little effort to avoid antagonizing China.

He has characterized climate change as a “Chinese hoax,” designed to undermine the American economy.

He has said China’s manipulation of its currency deepened a trade deficit with the United States. And he has threatened to impose a 45 percent tariff on Chinese goods, a proposal that critics said would set off a trade war.

By happenstance, just hours before Mr. Trump’s conversation with Ms. Tsai, Henry A. Kissinger, the former secretary of state who designed the “One China” policy, was in Beijing meeting with Xi Jinping.

By happenstance, just hours before Mr. Trump’s conversation with Ms. Tsai, Henry A. Kissinger, the former secretary of state who designed the “One China” policy, was in Beijing meeting with Xi Jinping.

It was unclear if Kissinger, 93, was carrying any message from Mr. Trump, with whom he met again recently in his role as the Republican Party’s foreign policy sage.

“The presidential election has taken place in the United States and we are now in the key moment. We, on the Chinese side, are watching the situation very closely. Now it is in the transition period,” Xi told Mr. Kissinger in front of reporters.

“The presidential election has taken place in the United States and we are now in the key moment. We, on the Chinese side, are watching the situation very closely. Now it is in the transition period,” Xi told Mr. Kissinger in front of reporters.

A faction of Republicans has periodically urged a more confrontational approach to Beijing, and many of President George W. Bush’s advisers were pressing such an approach in the first months of his presidency in 2001.

But the attacks of Sept. 11 defused that move, and Iraq became the No. 1 enemy.

After that, Bush needed China — for North Korea diplomacy, counterterrorism and as an economic partner — and any movement toward confrontation was quashed.

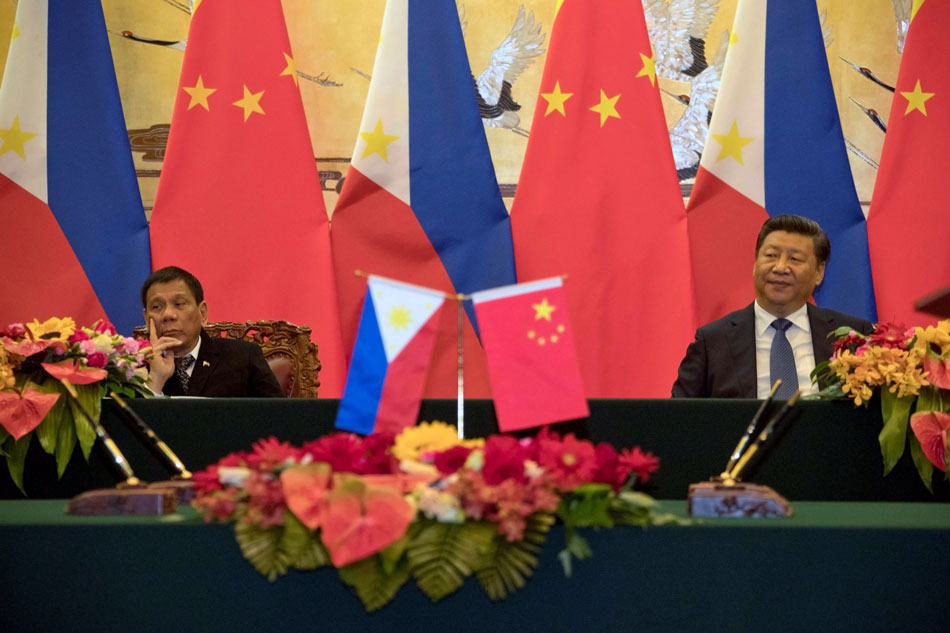

For his part, Mr. Trump has shown little concern about ruffling feathers in his exchanges with leaders. He also spoke on Friday with the Philippine president, Rodrigo Duterte, who has called Obama a “son of a whore” and been accused of ordering the extrajudicial killings of thousands of suspected drug dealers.

For his part, Mr. Trump has shown little concern about ruffling feathers in his exchanges with leaders. He also spoke on Friday with the Philippine president, Rodrigo Duterte, who has called Obama a “son of a whore” and been accused of ordering the extrajudicial killings of thousands of suspected drug dealers.

On Saturday, Duterte said that Mr. Trump had wished him well in his antidrug campaign, though his account could not immediately be verified.

This week, Mr. Trump appeared to accept an invitation from Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to visit Pakistan, a country that Mr. Obama has steered clear of, largely over tensions between Washington and Islamabad over counterterrorism policy and nuclear proliferation.